Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 8/52

Daisetz Suzuki: Spreading Zen to the West and refreshing its spirit

Among the pivotal figures who shaped the modern understanding of Zen Buddhism, few stand as prominently as Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (1870–1966). Through his translations, lectures, and writings, Suzuki introduced Zen to a broad Western audience at a time when Eastern thought was little known outside Asia. His portrayal of Zen emphasized direct experience, psychological depth, and existential insight, making it accessible to scholars, artists, and spiritual seekers worldwide. In doing so, Suzuki not only transformed Western perceptions of Zen but also revitalized its spirit within Japan.

‘Objective moral facts exist in all possible universes’ – A reflection on Richard Carrier’s latest article

Richard Carrier’s recent 2025 peer-reviewed paper, published in Religions (MDPI), presents a rigorous and provocative argument: that objective moral facts not only exist, but must exist in all possible universes containing rational agents, and, crucially, that God is not needed to ground them. This claim challenges both divine command theory and moral relativism. In this post, I’d like to summarize Carrier’s key arguments and interpret them in the light of my recent blog posts.

Hakuin Ekaku and his role in the revitalization of Rinzai Zen

Among the many figures in the history of Zen Buddhism, few have had as lasting an impact as Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769). Active during the Edo period in Japan, Hakuin is often credited with reviving and reshaping the Rinzai school (Rinzai-shū) of Zen, which had, by his time, fallen into stagnation and formalism. Through his emphasis on rigorous training, kōan practice, and the integration of Zen insight into daily life, Hakuin reenergized a tradition that would come to define Japanese Zen for centuries to follow. In this post, we explore Hakuin’s teachings, his innovations in Zen practice, and his role in reaffirming the vitality of the Rinzai tradition.

Bankei’s ‘The Unborn’

Among the many distinctive voices in the history of Zen Buddhism, few are as direct and refreshingly unembellished as Bankei Yōtaku (1622–1693). A Rinzai Zen master active during the early Edo period in Japan, Bankei taught a vision of awakening that bypassed ritual, study, and even formal meditation. At the heart of his message was a single, potent term: the Unborn (fushō). But what did Bankei mean by the Unborn? And how does this concept relate to the broader Mahāyāna doctrine of Buddha-Nature (tathāgatagarbha) and to the Buddhist view of reality as impermanent, process-based, and selfless? In this post, we address these questions and explore Bankei’s deeply human and accessible approach to Zen practice.

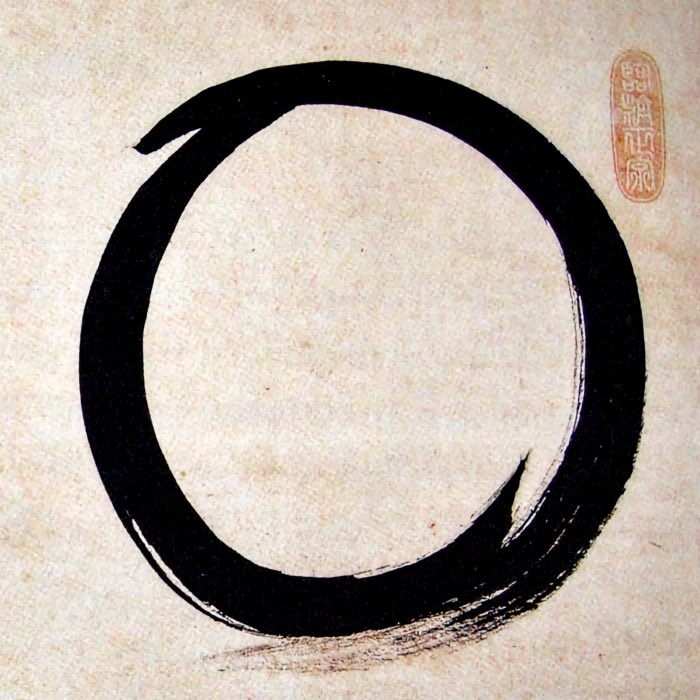

Mosshōseki: What does it mean to leave no trace behind?

Zen teaching emphasizes not only the importance of mindfulness and compassion but also the manner in which actions are carried out and let go. Among its subtle principles is Mosshōseki — the idea of living and acting without leaving traces of attachment or self-reference. In this post, we explore the meaning of Mosshōseki, its Buddhist foundations, and its practical application in daily life, reflecting a central dimension of the Zen approach to freedom and responsibility.

Shinshin: The unity of mind and body

Shinshin (心身), translated as ‘mind and body’, refers to the inseparability of mental and physical processes in Zen practice. While the dualistic division of mind and body has shaped much of Western philosophical tradition, Zen, following the broader Buddhist understanding, emphasizes that mind and body are not two independent substances but intimately interwoven aspects of experience. Shinshin points toward the realization that awakening is not confined to mental states alone but is embodied, enacted, and experienced through the totality of one’s being. This foundation also prepares the ground for the more specific integration of mind, skill, and body discussed in the concept of shingitai, where Zen practice further refines the unity of presence into dynamic engagement with action and technique.

Shingitai: The unity of mind, technique, and body

Shingitai (心技体), meaning ‘mind, technique, and body’, describes a comprehensive integration of internal attitude, skillful action, and physical embodiment. Although the term is especially well known in Japanese martial arts, it has deep resonance within Zen, where practice is never purely mental or purely physical but demands a total engagement of being. In the Zen context, shingitai highlights that awakening is not a matter of intellectual insight alone, but of the seamless unity of thought, behavior, and presence.

Kansha: Gratitude as a Zen practice

Kansha (感謝), translated as ‘gratitude’ or ‘thankfulness’, represents a mental attitude of deep appreciation in Zen practice. While gratitude is universally recognized as a virtue across cultures and traditions, its significance within Zen extends beyond conventional thankfulness for favorable conditions. In Zen, kansha embodies a radical acceptance and appreciation of all aspects of life, including hardship, impermanence, and loss, as integral parts of the unfolding reality. It expresses a mature insight that recognizes interdependence (engi) and the non-separateness of self and world.

Gaman: Enduring patience in Zen

Gaman (我慢), often translated as ‘enduring patience’ or ‘perseverance with dignity’, is a mental attitude highly valued not only in Japanese culture broadly but also within Zen practice. In the Zen context, gaman signifies the capacity to endure discomfort, difficulty, or adversity without complaint, agitation, or withdrawal. Unlike passive resignation, gaman is an active endurance grounded in clarity and acceptance of reality as it is. It reflects a profound cultivation of equanimity (upekkhā) and patience (khanti), central virtues within the Buddhist path.

Shisei: Posture as mind-body presence in Zen

Shisei (姿勢), often translated as ‘posture’ or ‘attitude’, refers not only to physical alignment but to the integration of body and mind (shinshin) in Zen practice. While many traditions emphasize mental cultivation in abstract terms, Zen insists on the inseparability of mental and physical states. Posture is not merely a support for meditation — it is meditation. Shisei thus becomes a key expression of embodied presence, where the way one sits, walks, bows, or breathes reflects and shapes one’s state of mind.