Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 6/52

Stūpas: Sacred architecture of Buddhism

The stūpa is one of the most iconic and enduring forms of Buddhist sacred architecture. Emerging from ancient Indian burial traditions, it evolved into a structure that not only houses relics but also embodies the cosmological and spiritual worldview of Buddhism. Unlike conventional buildings, the stūpa is not meant to be entered. It is meant to be circumambulated, meditated upon, and venerated, making it as much a ritual space as an architectural form. The stūpa has served multiple roles: a reliquary for the remains of the Buddha and other enlightened figures, a symbol of enlightenment itself, and a focal point for communal and devotional activity. Its significance extends beyond its physical design, integrating symbolism, ritual, and identity across Buddhist traditions. This post offers a historical and architectural overview of the stūpa, tracing its development from ancient India to its regional adaptations across Asia. We also examine how the stūpa functions as a medium of religious expression and cultural continuity within the broader Buddhist world.

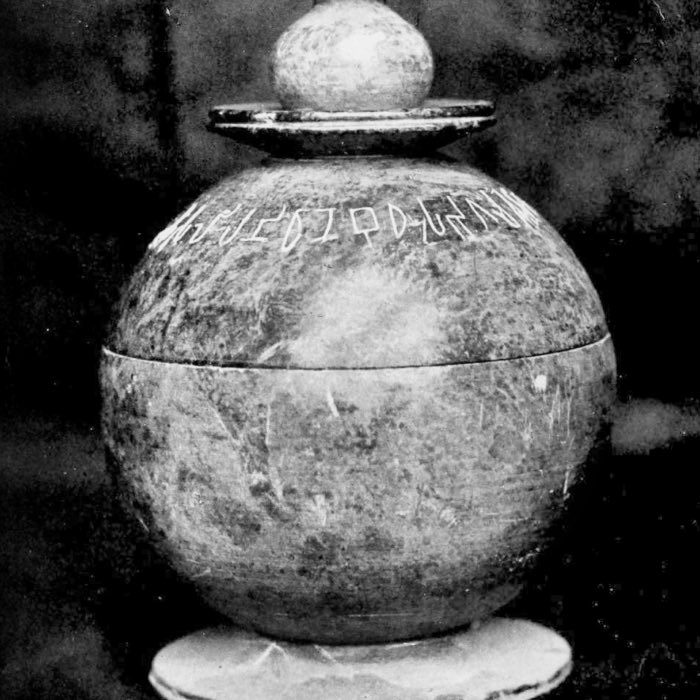

Piprahwa: The Buddha’s relics and the history of their archaeological discovery

For more than a century, the Piprahwa stūpa has captivated archaeologists, epigraphers, and historians of Buddhism. As the site of a controversial yet remarkably early inscription that may refer to the historical Buddha, it holds both archaeological promise and interpretive tension. Discovered in the colonial era and revisited by modern researchers, Piprahwa offers a rare case where textual tradition, ritual architecture, and material remains converge. In this post, we briefly examine the discovery, debates, and evolving significance of Piprahwa in the ongoing effort to understand the historical foundations of Buddhism.

Archaeology of Buddhist sites: Tracing the historicity of early Buddhism

Buddhism is not only a system of philosophical insight and religious practice, but also a historical tradition grounded in the biography of its founder. While Siddhartha Gautama has long been the subject of canonical texts and devotional legends, archaeology offers a complementary perspective: one grounded in material remains, inscriptions, and the spatial development of sacred sites. In this post, we explore the scientific investigation of the most important places traditionally associated with Siddhartha’s life. We also examine what archaeology can contribute to our understanding of Siddhartha’s historicity and the earliest phases of Buddhist institutional development, while aiming to provide a nuanced perspective that balances faith and historical inquiry.

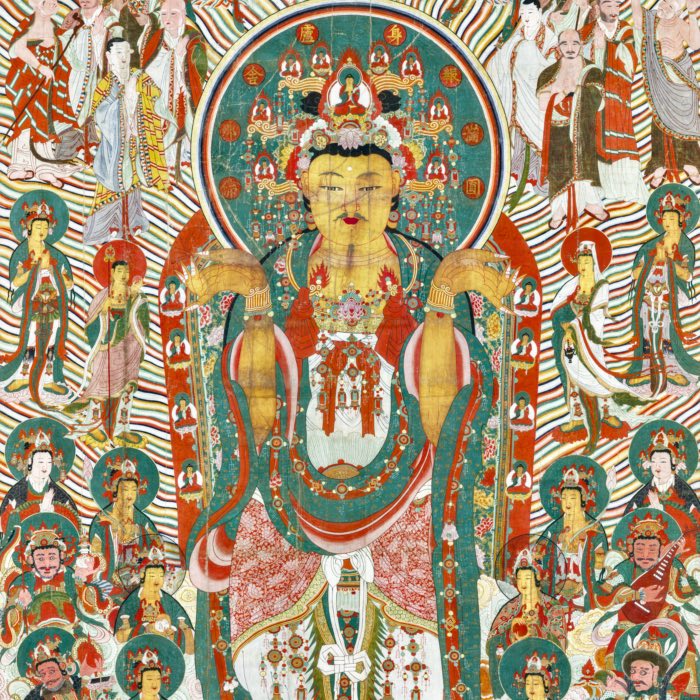

Amitābha Buddha: The Buddha of infinite light

Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, is one of the most revered figures in Mahāyāna Buddhism, embodying boundless compassion and wisdom. As the presiding Buddha of the Pure Land of Sukhāvatī, Amitābha offers a path to liberation that is accessible to all beings through faith, aspiration, and devotion. In this post, we explore the origins, symbolism, and practices associated with Amitābha, highlighting his profound role in Buddhist soteriology and his relevance across cultures and traditions.

Avalokiteśvāra: The embodiment of compassion

Avalokiteśvāra, the bodhisattva of compassion, is one of the most beloved and enduring figures in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. Revered across cultures and traditions, he embodies the ideal of boundless compassion and the commitment to alleviate the suffering of all beings. This post explores Avalokiteśvāra’s origins, iconography, philosophical significance, and cultural adaptations, highlighting his role as both a devotional focus and an ethical model for practitioners on the path to awakening.

Adibuddhas and the Five Tathāgatas

The concept of the Adibuddha, or ‘primordial Buddha’, represents one of the most profound developments in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. Unlike historical Buddhas such as Siddhartha Gautama, the Adibuddha is timeless and unconditioned, symbolizing the ultimate source of all awakened activity. Closely linked to the Five Tathāgatas, archetypal Buddhas embodying distinct aspects of enlightened awareness, this framework offers a rich cosmological and psychological model for understanding the nature of reality and the path to awakening. In this post, we explore the origins, symbolism, and transformative practices associated with the Adibuddha and the Five Tathāgatas, highlighting their enduring relevance in Buddhist thought and practice.

Buddhist eschatology and the future Buddha Maitreya

Maitreya, the future Buddha, holds a central place in Buddhist eschatology as the prophesied restorer of the Dharma in an age of moral and spiritual decline. Unlike apocalyptic visions in other traditions, Buddhist eschatology envisions cycles of decay and renewal, with Maitreya symbolizing hope, ethical restoration, and the continuity of the teachings. In this post, we examine Maitreya’s doctrinal significance, devotional practices, and cultural adaptations, highlighting his relevance across Buddhist traditions.

Yakṣas, Nāgas, and other semi-divine beings in Buddhism

Buddhism’s rich cosmology includes a fascinating array of semi-divine beings such as yakṣas, nāgas, and asuras. These figures, drawn from pre-Buddhist Indian traditions, were not discarded but reinterpreted and integrated into the Buddhist worldview. Serving as protectors, moral exemplars, or cautionary tales, these beings illustrate the universality of karmic law and the potential for transformation. In this post, we explore their roles, symbolism, and relevance in Buddhist practice and culture.

The Jātakas: The tales of Siddhartha’s past lives

The Jātakas, or tales of the Buddha’s past lives, are among the most cherished and enduring narratives in Buddhist literature. These stories depict Siddhartha Gautama’s journey as a Bodhisatta across countless lifetimes, illustrating his cultivation of virtues such as generosity, patience, and wisdom. Far from being mere folklore, the Jātakas serve as ethical guides, soteriological models, and cultural treasures, offering profound insights into the Buddhist path of moral and spiritual development.

Buddhist vs. Hindu cosmology: Inheritance, divergence, and polemical transformation

Cosmology in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions serves a dual function: it is not only a descriptive model of the universe’s structure and temporal cycles but also a normative framework that shapes ethical behavior, ritual practice, and spiritual aspiration. In this light, cosmological systems are never value-neutral; they articulate worldviews that define the meaning of life, the nature of reality, and the goals of religious practice. This comparison aims to clarify how Buddhist cosmology inherited and adapted elements of earlier Vedic and later Hindu frameworks while also reformulating them in line with its core doctrines, particularly anattā (non-self), dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda), the nature of suffering (dukkha), and the path to liberation (nirvāṇa). The distinction between structural borrowing and doctrinal transformation is essential. What may look like continuity in myth or imagery often masks deep differences in philosophical orientation and soteriological intent.