Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 9/36

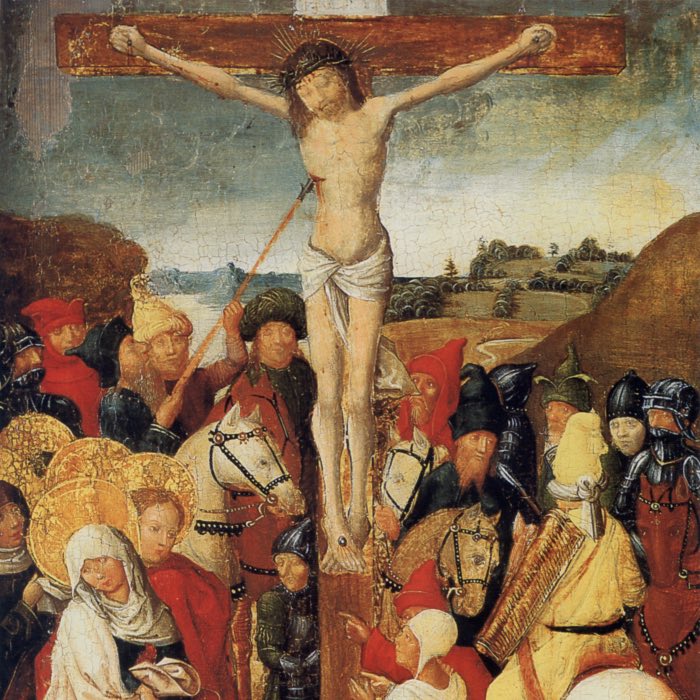

The role of sacrificial blood rituals in Judaism and its reinterpretation in Christianity

Blood sacrifice holds a profound and complex role within the context of Jewish religious tradition, reflecting both its ancient cultural origins and its theological evolution. This symbolism extends into the early Christian reinterpretation of sacrificial practices, culminating in the belief in Jesus’ sacrificial death. In this post, we take a closer look at these practices within their historical and cosmological frameworks ti better understand why blood sacrifice was seen as essential and how it became a central theme in the development of Christianity – whether Jesus is viewed as a historical figure or a ‘celestial construct’.

Why did Jewish apocalypticism culminate in the 1st century CE?

Throughout history, human societies have often grappled with the notion of an impending apocalypse — a final, cataclysmic event that would reshape or end the world as they knew it. For the Jewish people, the idea of doomsday gained prominence during their tumultuous history under foreign rule, evolving into a complex eschatological framework that would later influence Christianity. Inspired by a talk I recently watched by Richard Carrier titled ‘From Noah’s Flood to Rapture Day’, this post explores the origins and development of Jewish apocalyptic beliefs, tracing their roots from Persian Zoroastrian influences to the widespread messianic fervor of the 1st century CE. We will explore how these beliefs culminated in a series of failed messianic movements and ultimately shaped the emergence of Christianity as a surviving apocalyptic sect.

Zalmoxis: The Thracian cult that may have influenced the conception of Jesus

Zalmoxis is a figure deeply rooted in the spiritual traditions of the ancient Thracians, specifically the Getae, a tribe inhabiting regions corresponding to modern-day Romania and Bulgaria. His narrative, as recorded by ancient Greek sources such as Herodotus, portrays him as a teacher, prophet, or even a god who profoundly influenced the religious and philosophical outlook of the Getae. Beyond his historical and mythological significance, Zalmoxis has become a focal point in modern discussions about the origins and development of mystery cults in antiquity. In this post, we explore Zalmoxis’s role in Thracian religion, his connections to Greek mystery traditions, and Richard Carrier’s interpretation of his cult’s significance as a precursor to Christianity.

Enoch: Another exemplar for the Jesus narrative?

The mythological framework surrounding early Christianity has been a topic of considerable debate a long time. Among scholars who advocate a non-historical or mythological Jesus, such as Richard Carrier, the evolution of Jesus as a theological construct becomes a lens through which the influence of apocryphal texts can be assessed. One of the key texts in this discourse is the Book of Enoch (also known as 1 Enoch), a Jewish pseudepigraphal work that profoundly shaped Second Temple Jewish thought.

Philo of Alexandria’s logos concept and its potential influence on the development of the Jesus narrative

The question of how early Christians conceptualized Jesus and whether this figure was initially understood as a historical person or a celestial being has fueled significant scholarly debate. One prominent hypothesis, advanced by Richard Carrier, suggests that the original Christian understanding of Jesus was as a celestial being, akin to an angel or intermediary figure, who was later historicized into a real human person. Central to Carrier’s argument is the idea that this celestial Jesus may have been influenced by earlier Jewish theological constructs, particularly Philo of Alexandria’s writings about the logos. However, while Philo’s logos shares certain attributes with the early Christian depiction of Jesus, Philo never names this figure ‘Jesus’ or explicitly associates it with the messianic figure of Christian tradition. This post explores Philo’s concept of the logos, its relationship to angelic intermediaries, and Carrier’s argument that early Christians conceived of Jesus as a celestial being modeled after such theological constructs.

Richard Carrier and the historicity of Jesus: Was Christianity born from a mystery cult?

The question of whether Jesus of Nazareth was a historical individual or a purely mythical figure has long engaged theologians, historians, and laypeople alike. In his book, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (2014), Richard Carrier challenges conventional scholarly assumptions and proposes that Christianity could have originated without a historical founder. Instead, it might represent a Jewish adaptation of what Carrier calls a ‘mystery cult, following patterns already established in other ancient Mediterranean religious traditions. Drawing upon the scholarly consensus, methodological critiques, parallel religious traditions, textual analysis of the Pauline epistles, and the literary nature of the gospels, Carrier puts forth an argument suggesting that early Christians may have begun with the worship of a celestial Jesus and only later placed him into human history. This post summarizes and expands upon the main lines of argument Carrier presents, based on a recorded talk in which he outlines the major findings of his research.

The mythological character of the Gospels: A critical examination of Richard Carrier’s theories

The figure of Jesus Christ has been central to Western civilization for nearly two millennia, yet the nature of the New Testament narratives remains a matter of intense debate. Richard Carrier, an American historian and philosopher, has argued that early Christian texts, particularly the gospels, are not historical biographies but mythological constructs designed to convey theological truths. This hypothesis places the gospel accounts within a broader tradition of ancient religious storytelling, where myth and symbolism often served as vehicles for spiritual meaning.

How Paul’s epistles engineered early Christianity

The epistles of Paul, often regarded as the cornerstone of Christian theology, were among the earliest written documents of the New Testament. Far from casual correspondence, these letters were carefully constructed to address pressing issues within emerging Christian communities. Their content reveals not only Paul’s theological convictions but also his strategic efforts to unify diverse groups, define doctrinal foundations, and establish his authority as a leader within the early church. In this post, we explore the intentionality behind Paul’s epistles, analyze their historical context, theological objectives, and their profound impact on the development of Christianity.

Scriptures rewritten: How pseudepigraphy shaped the New Testament

The New Testament, a foundational collection of texts for Christianity, consists of 27 books that span a range of literary genres, including historical narratives, theological treatises, letters, and apocalyptic visions. Traditional Christian views hold that these books were written by apostles or their close associates, lending them an air of direct apostolic authority. However, modern biblical scholarship has questioned the authenticity of several New Testament books, suggesting that many were forged or editorially reworked in antiquity. In this post, we explore the phenomenon of pseudepigraphy (writing in the name of another) in the New Testament, the historical context of forgery, and the implications for understanding early Christian communities.

Christianity: A syncretic religion in historical context

Christianity, as one of the world’s major religions, has long been the subject of extensive academic inquiry. Its origins, core teachings, and historical development have been studied through various disciplinary lenses, including theology, history, anthropology, and comparative religion. Scholars have debated how Christianity emerged, the nature of its earliest communities, and how it evolved into an institutionalized faith. In this post, we examine current scholarship on Christianity, focusing on its syncretic nature and historical context.