Weekend Stories sorted by tags

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

Back to stories · diary · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view

- African Culture 16

- American Culture 9

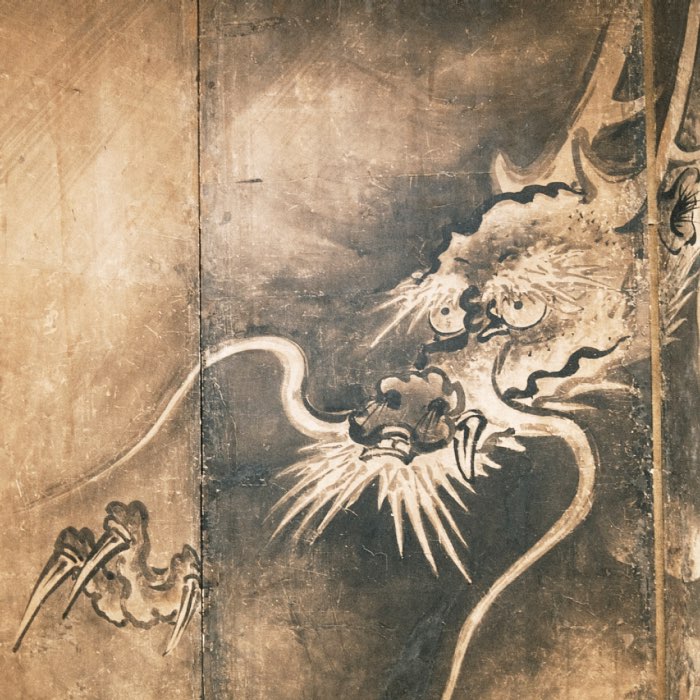

- Ancient Times 206

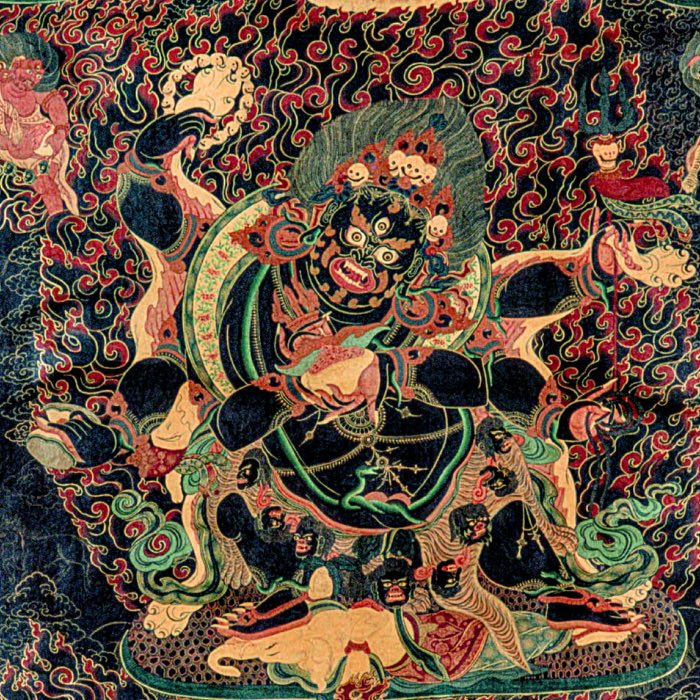

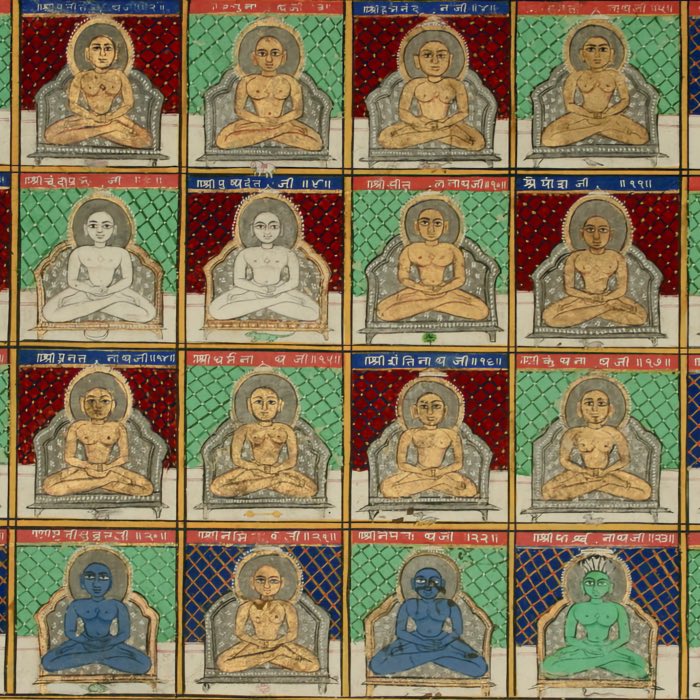

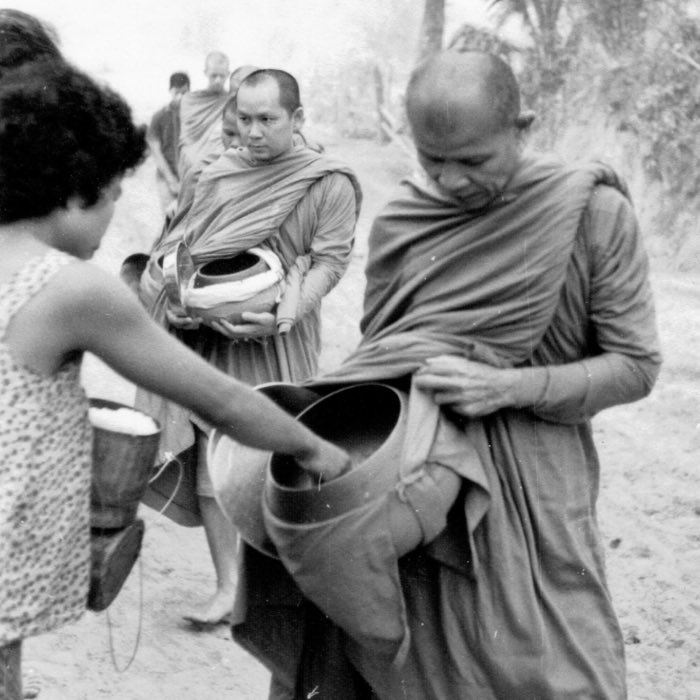

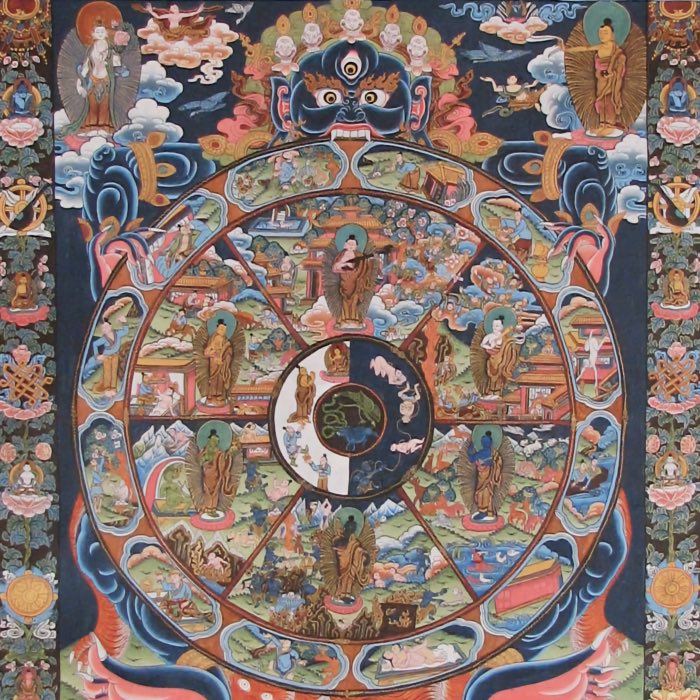

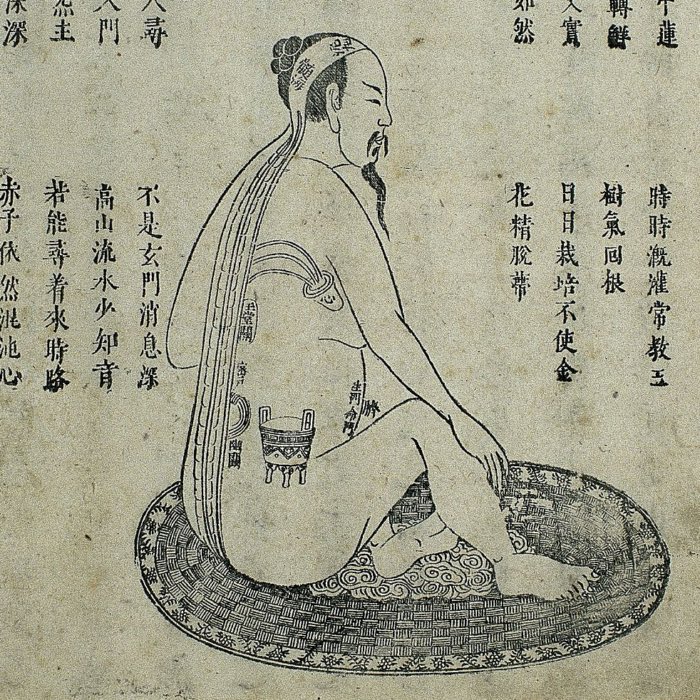

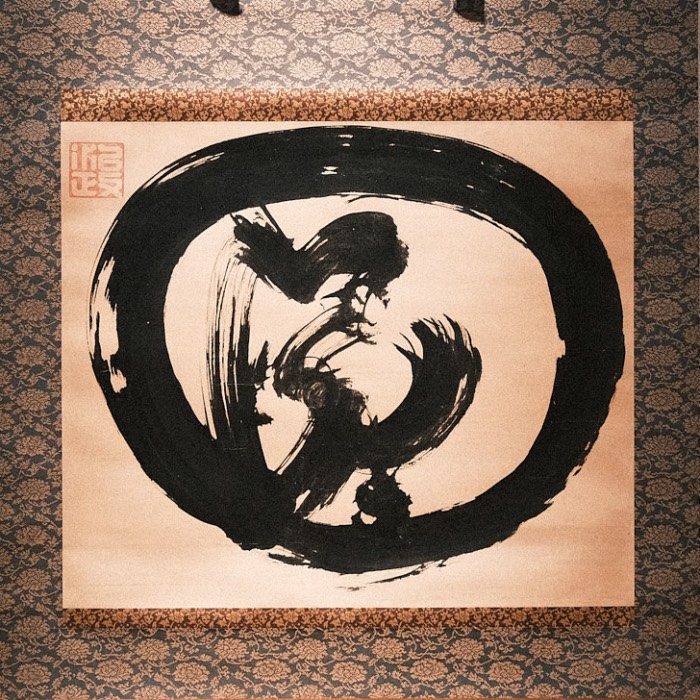

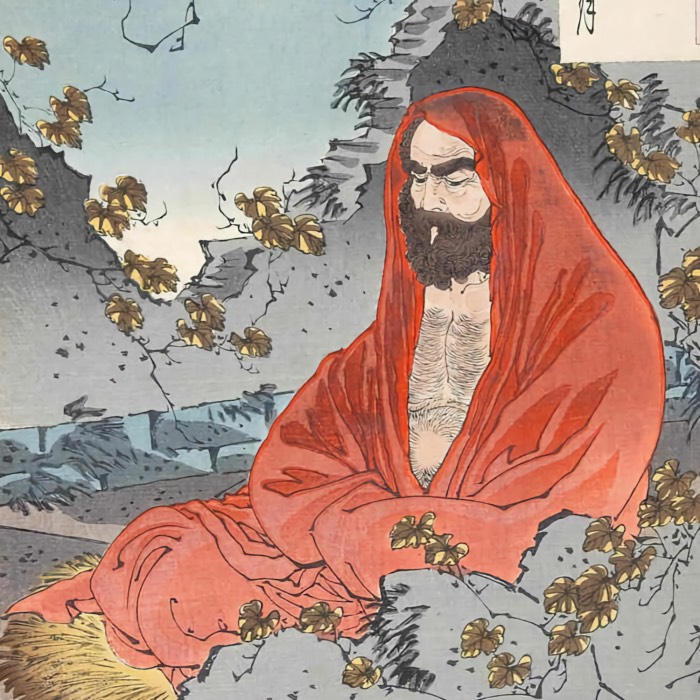

- Buddhism 46

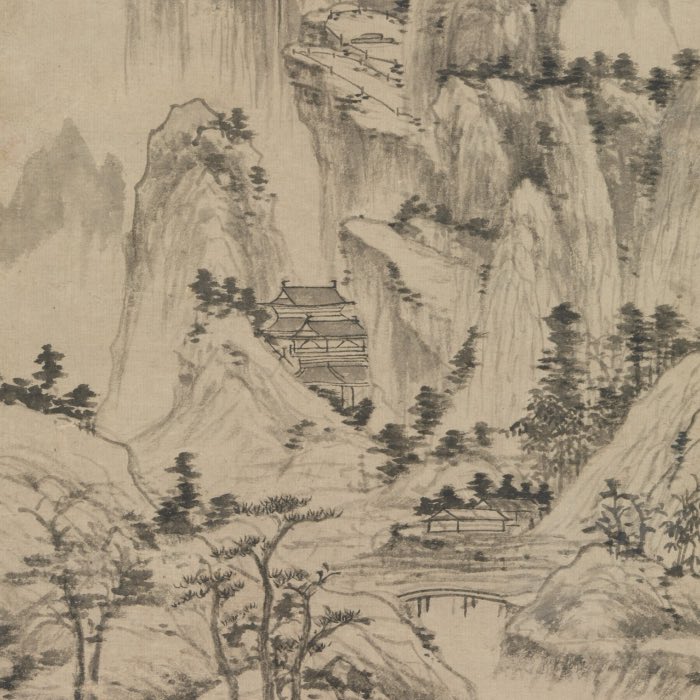

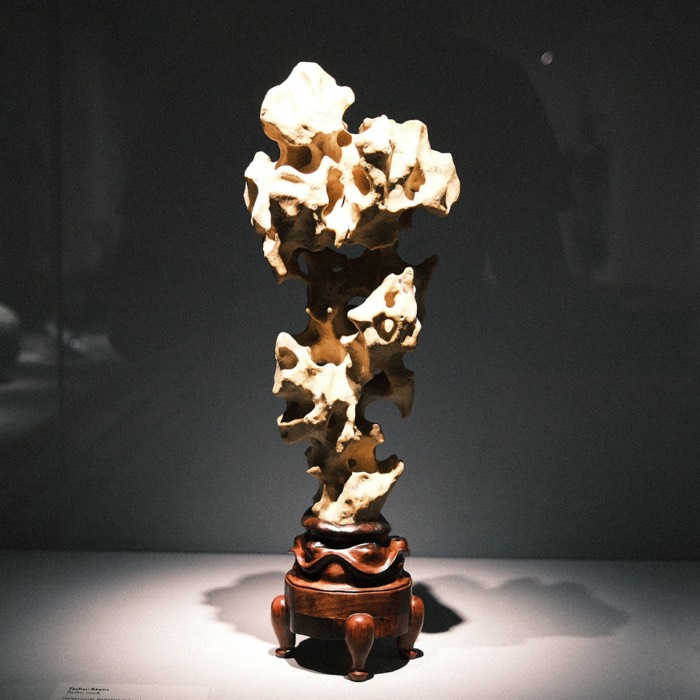

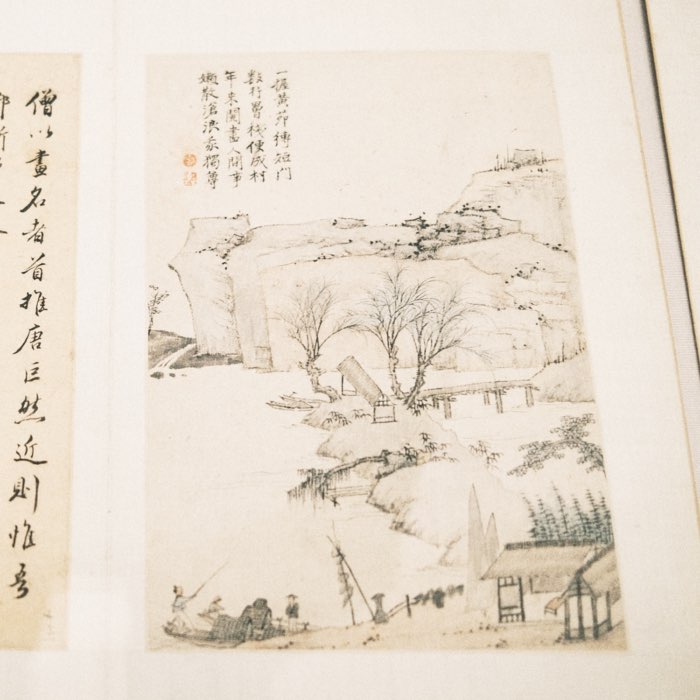

- Chinese Culture 40

- Cologne 59

- Comparative Studies 35

- Crimes Against Humanity 48

- Early Civilization 70

- Egyptian Culture 12

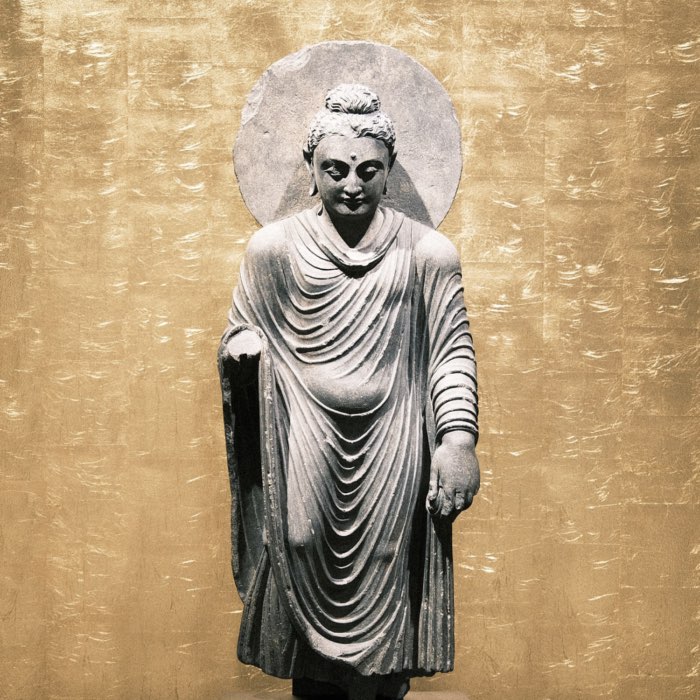

- Gandharan Art 5

- Greco-Roman Culture 110

- Greco-Roman Philosophy 54

- History as a Science 9

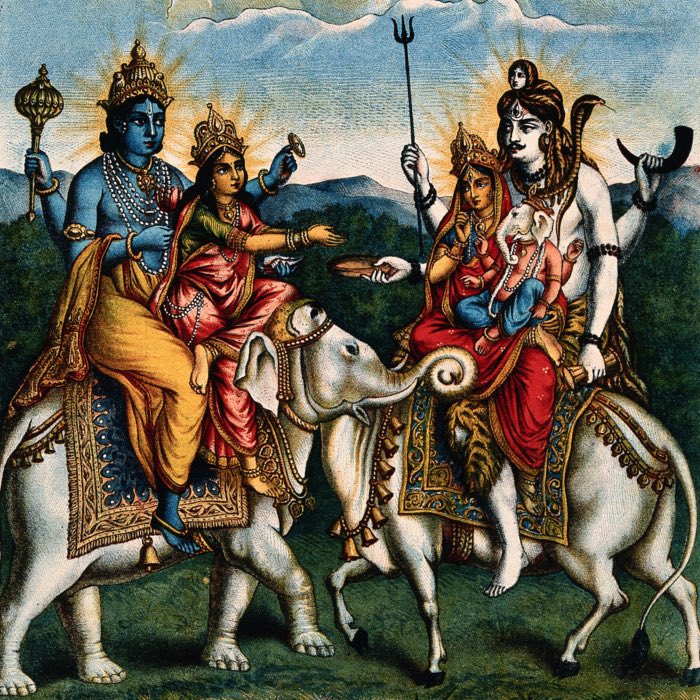

- Indian Culture 36

- Industrial History 6

- Islamic Culture 6

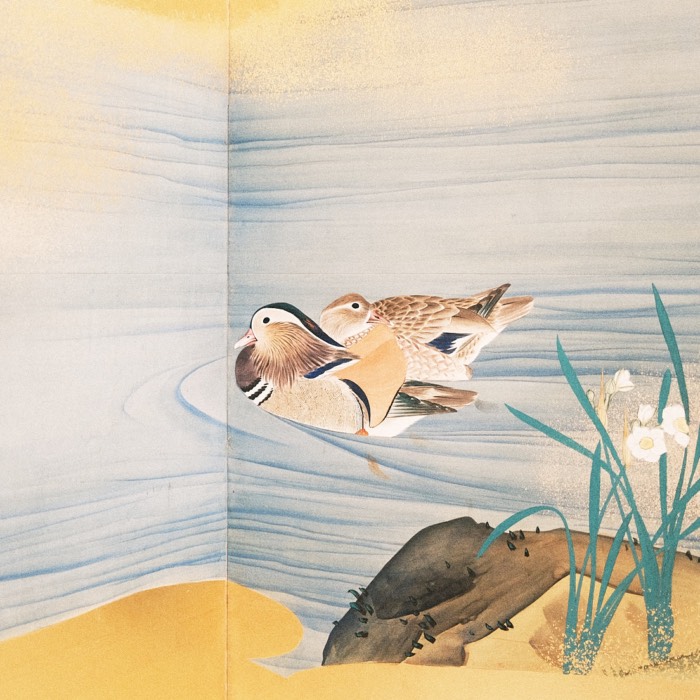

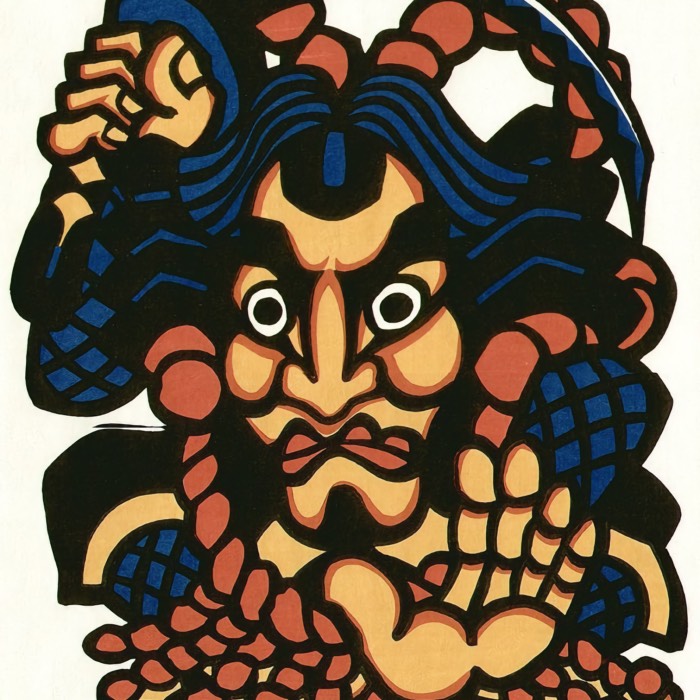

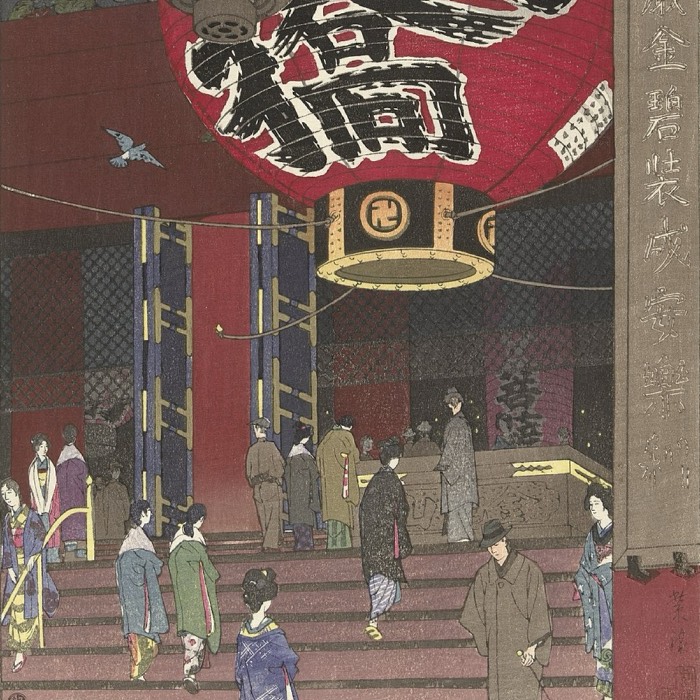

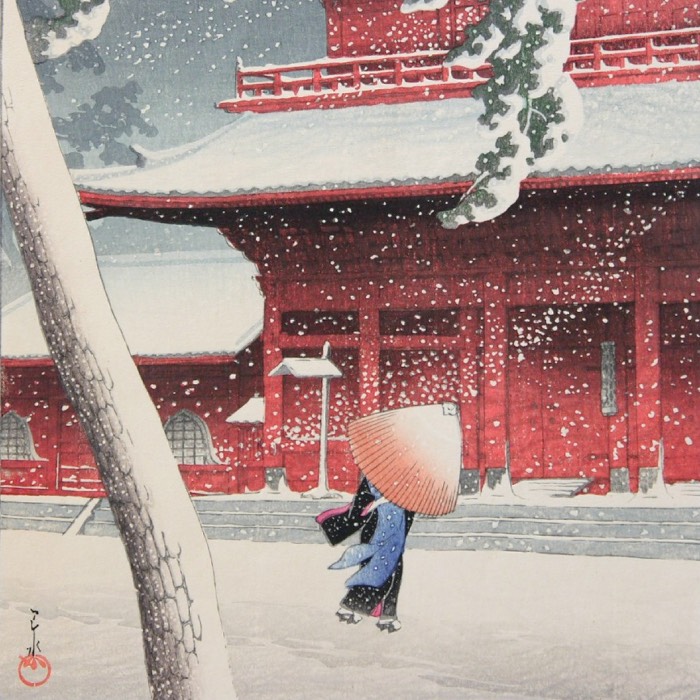

- Japanese Culture 56

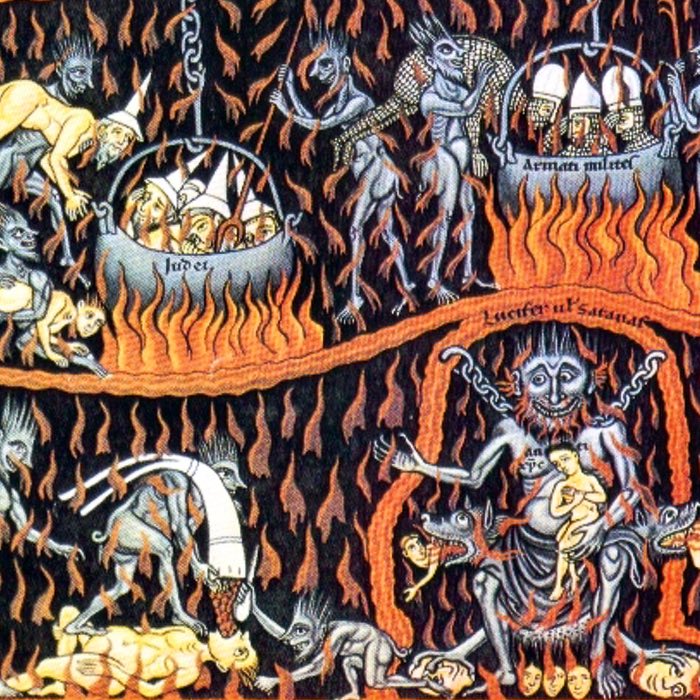

- Judaeo-Christian Culture 174

- Korean Culture 16

- LGBTQ+ 9

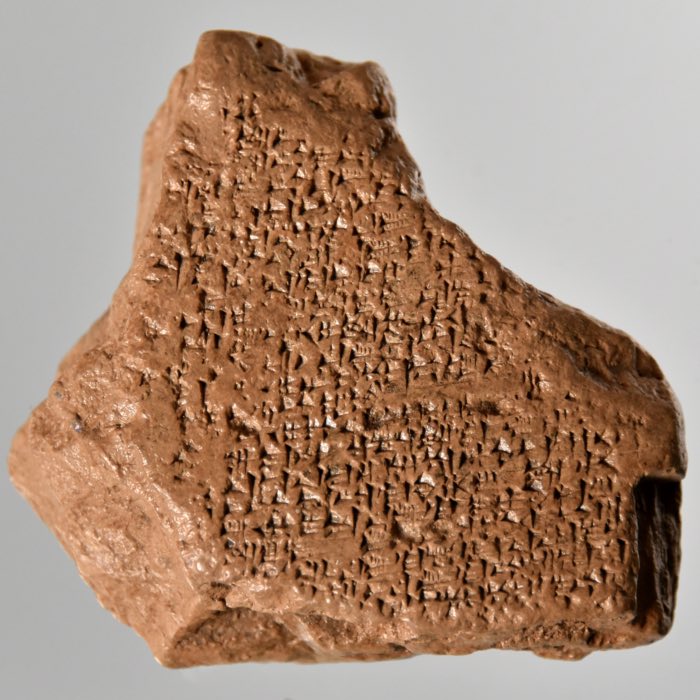

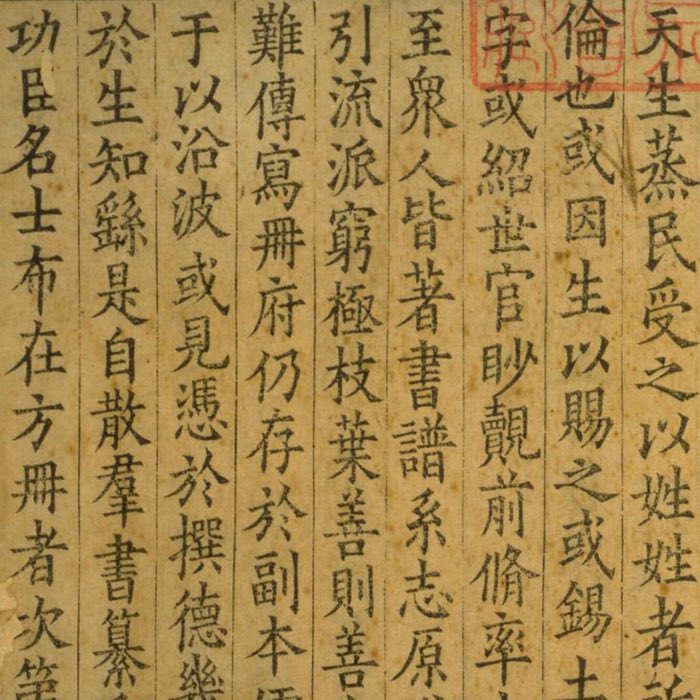

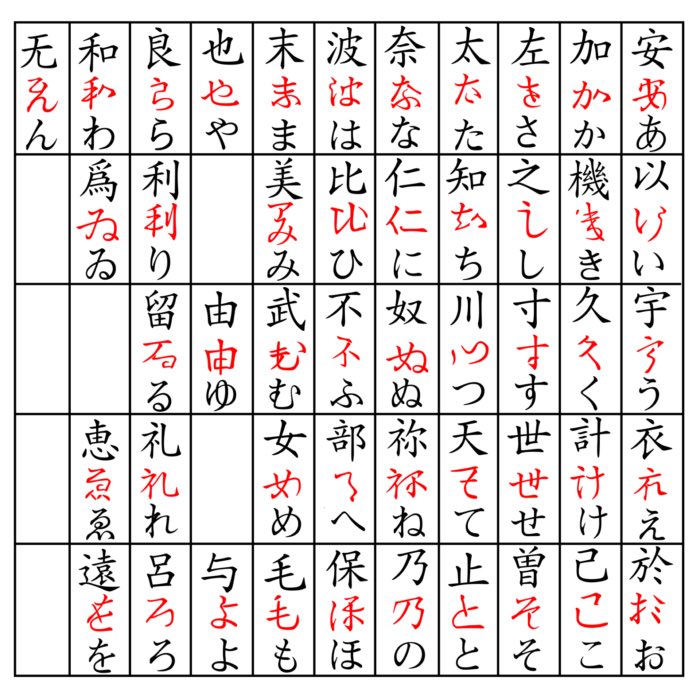

- Languages and Writing 19

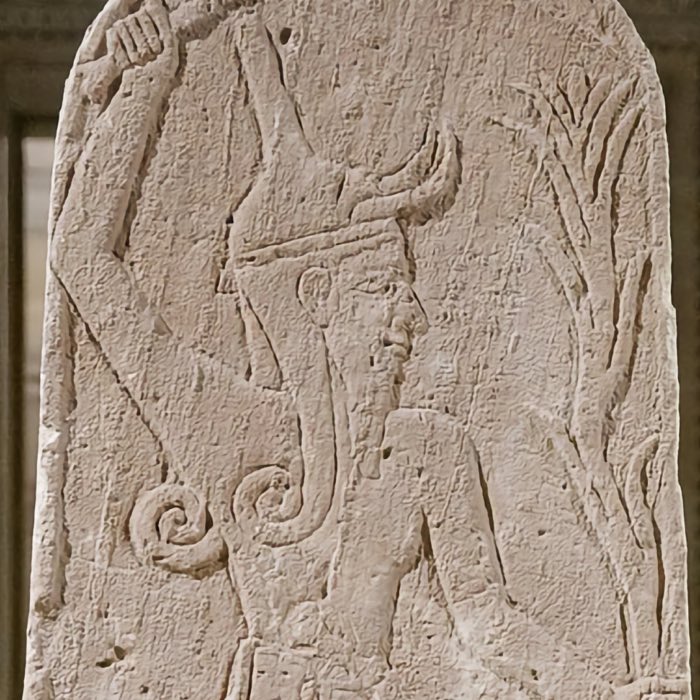

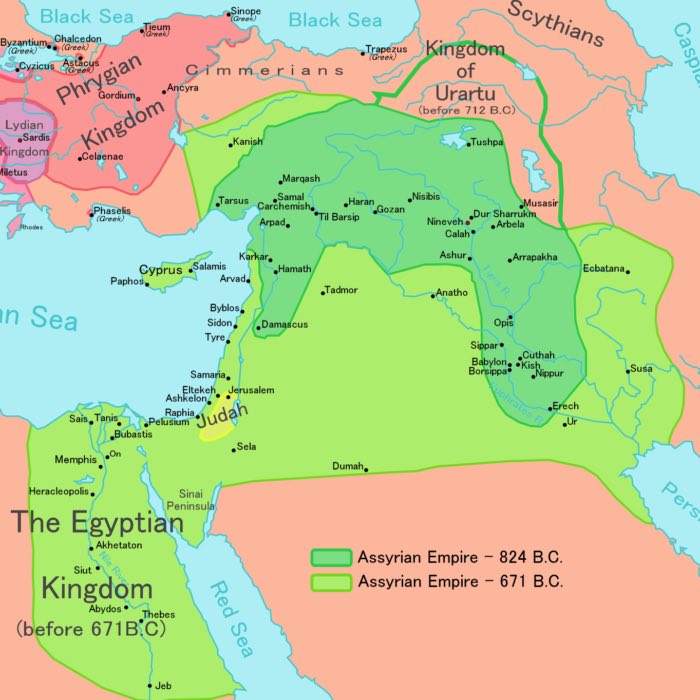

- Mesopotamian Culture 34

- Myanmar Culture 3

- Pottery and Ceramics 9

- Tea 3

- Thai Culture 5

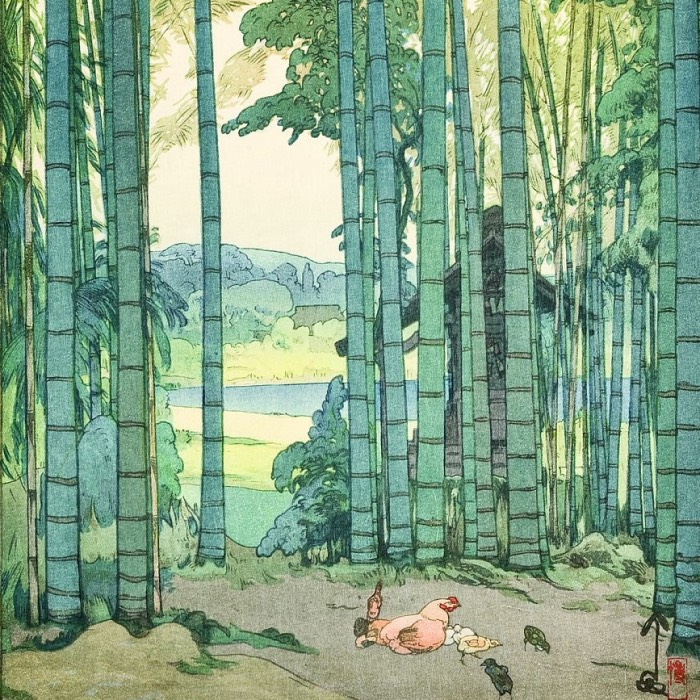

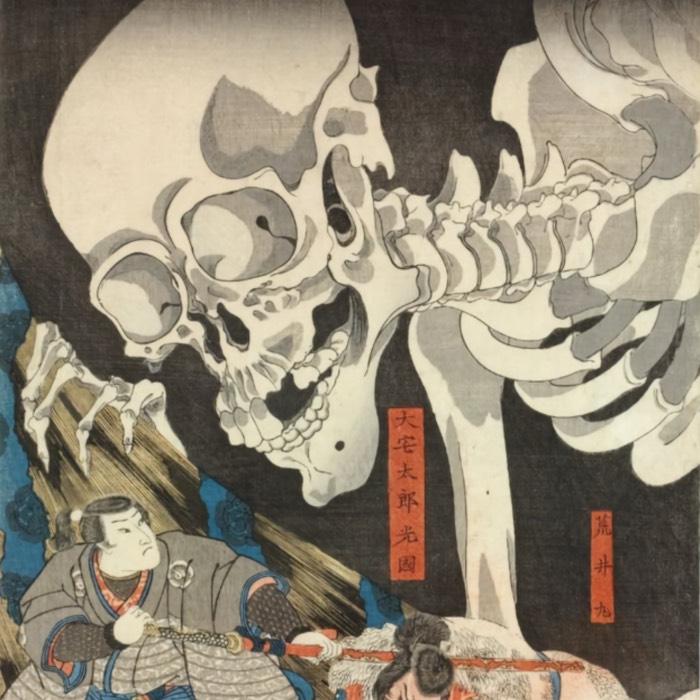

- Ukiyo-e and Shin-hanga 30

- Vietnamese Culture 5

#African Culture

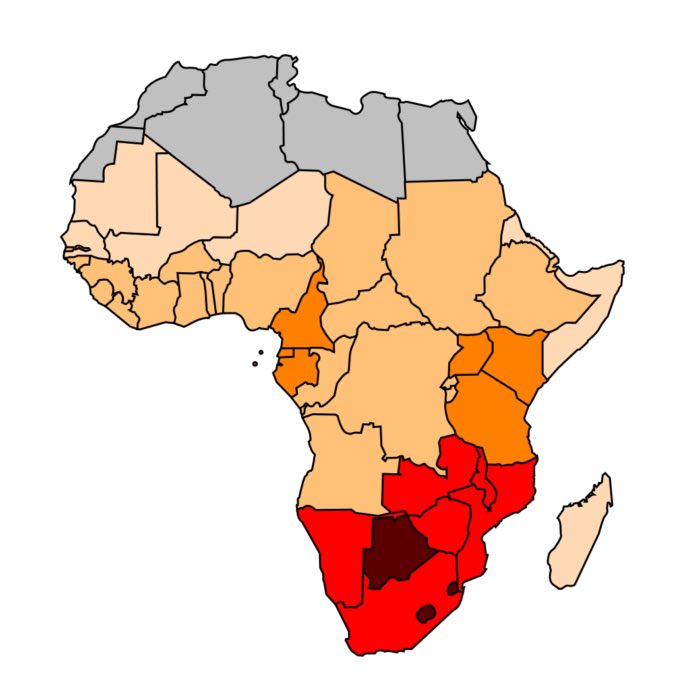

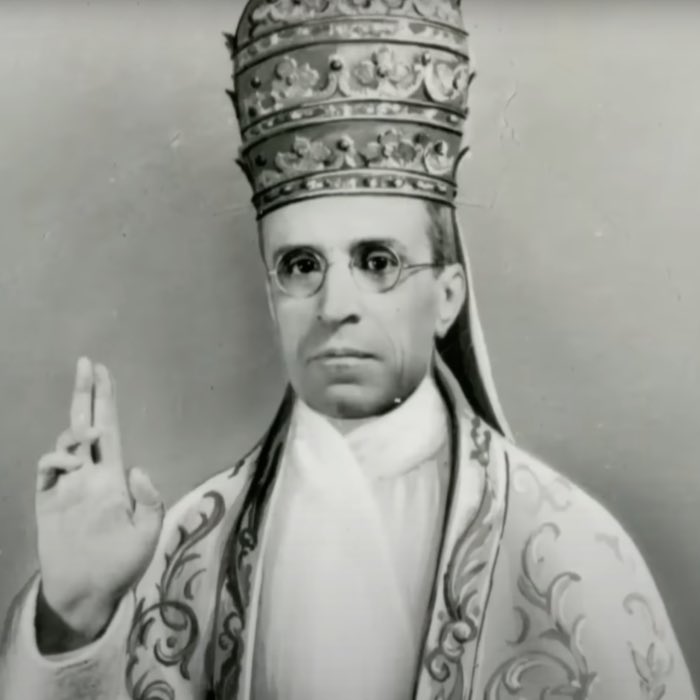

HIV/AIDS in Africa: How the Catholic Church's policies worsen the crisis

When I worked on the previous post on ‘Christianity’s death toll’, I was surprised to find out how many people are dying because of HIV/AIDS in Africa each year. The Catholic Church, which presents itself as a moral authority, has played a significant role in shaping public discourse on the epidemic. Its opposition to contraception, particularly condoms, has had dire consequences, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where millions of lives have been devastated by HIV/AIDS. While the Church advocates for chastity and fidelity as means of prevention, its outright rejection of condoms has led to unnecessary suffering and loss of life. I thought this topic warranted a dedicated post to further examine the facts behind this deeply cynical and destructive stance, as well as its impact on global health efforts.

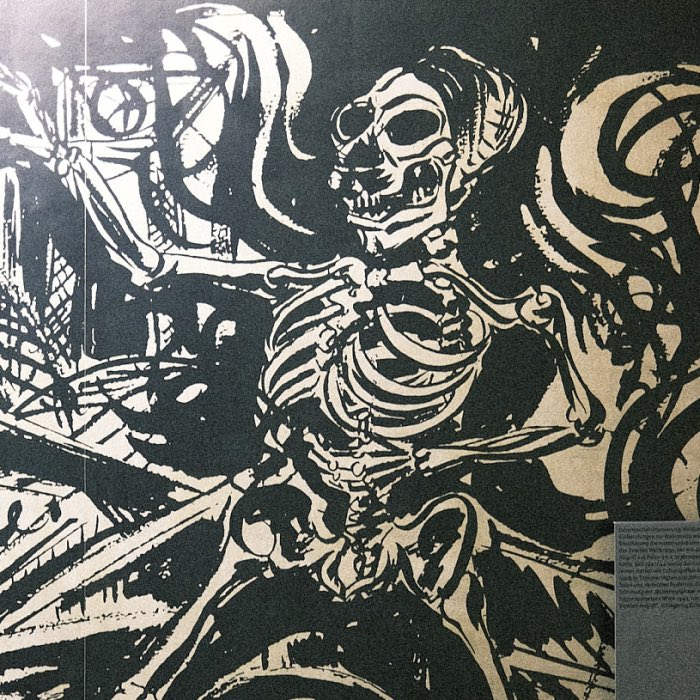

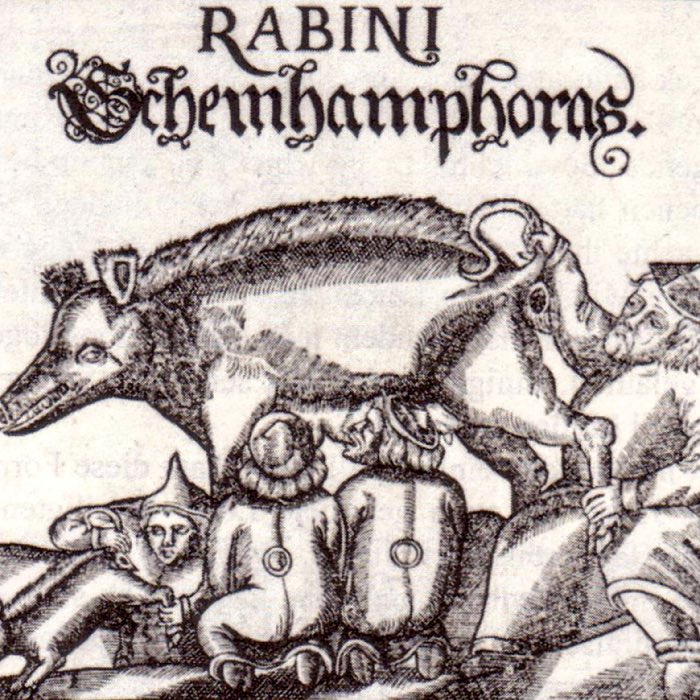

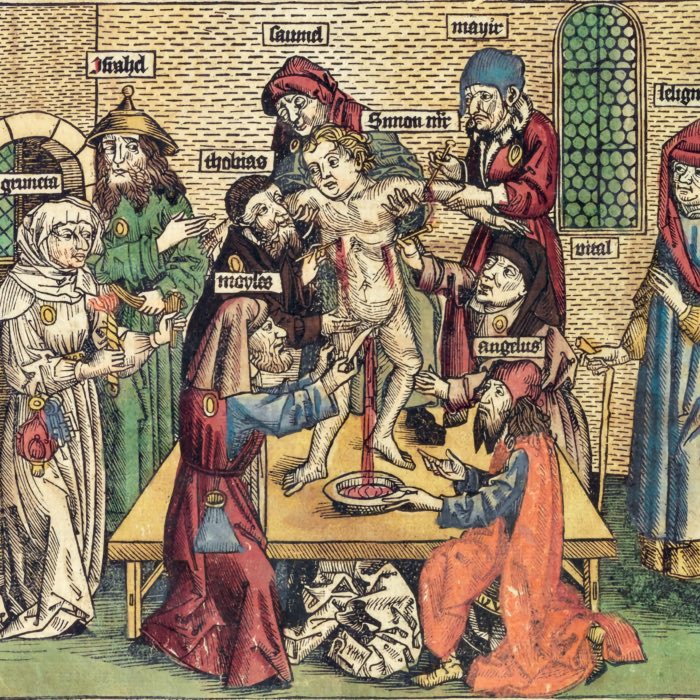

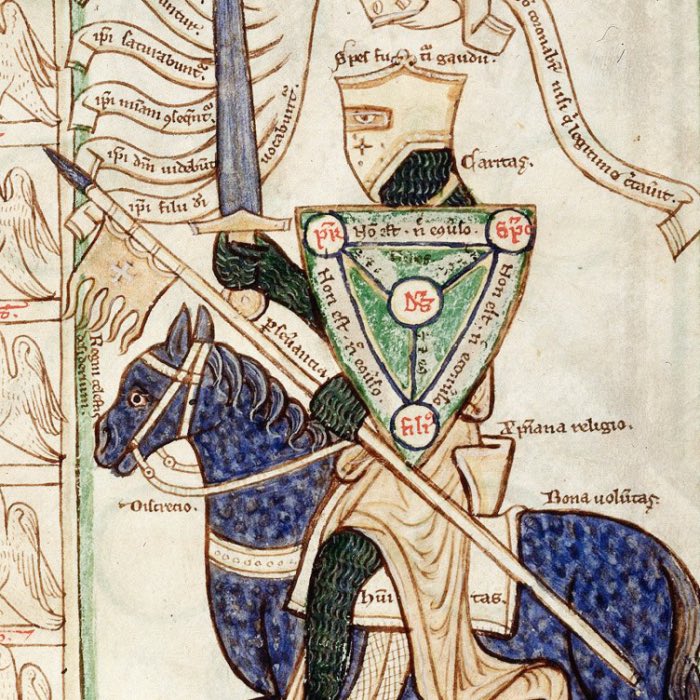

Christianity's death toll

The institutions of the Christianity has played a central role in shaping Western history for nearly two millennia, influencing political, social, and cultural developments on a global scale. Alongside its contributions to art, education, and social welfare, the Christianity has also been a catalyst for some of history’s most violent and destructive events. From the Crusades and inquisitions to pogroms and forced conversions, these actions have resulted in untold suffering and loss of life. This post seeks to critically examine the death tolls associated with Christianity’s direct and indirect actions, placing them within their historical contexts and exploring the moral and ethical implications of such a legacy.

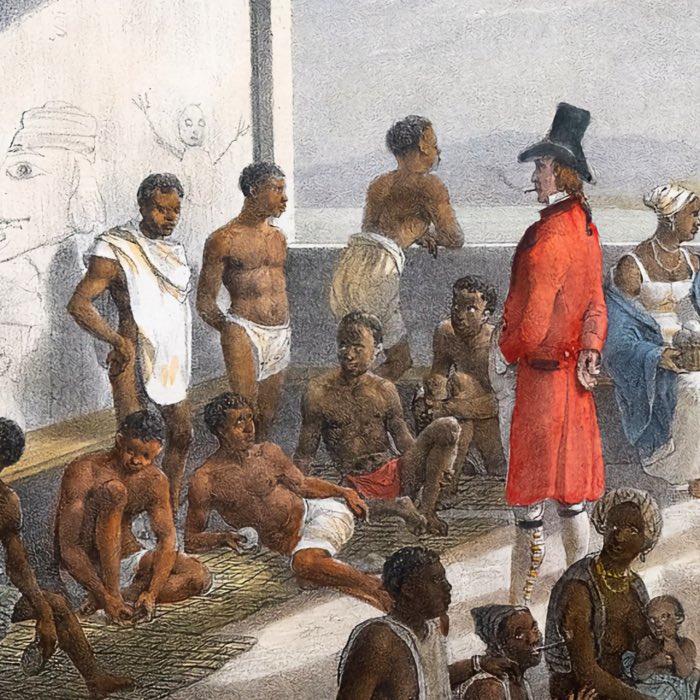

The Black Holocaust and the complicity of the Catholic Church

The Black Holocaust represents one of the most prolonged and devastating human atrocities in history. It encompasses the mass enslavement, exploitation, and extermination of African people, particularly through the Trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Atlantic slave trades. This prolonged system of oppression did not end with slavery’s formal abolition but continued through colonialism, imperialism, systemic racism, and the economic disenfranchisement of African and African-descendant populations worldwide. Central to this system was the role of the Catholic Church, which not only provided theological justification for the enslavement of Africans but also materially benefitted from it. Papal decrees facilitated European expansion and the trade of enslaved persons, while Church institutions engaged in and profited from slavery. Even after abolition, the Church was slow to confront its moral culpability, and its complicity remains a subject of historical reckoning.

The destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria in 391 CE: Christianity's shift from persecuted to persecutor

The destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria in 391 CE stands as one of the most emblematic events of Late Antiquity, symbolizing the dramatic transformation of Christianity from a persecuted minority to an institution wielding the power of the Roman state. This episode not only marked the decline of pagan religious practices in Alexandria but also reflected the broader social, political, and theological shifts that had accompanied the rise of Christianity as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. The destruction of this magnificent temple dedicated to the Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis offers profound insights into the dynamics of religious conflict, the role of Church authorities, and the consequences of imperial policies aimed at religious consolidation.

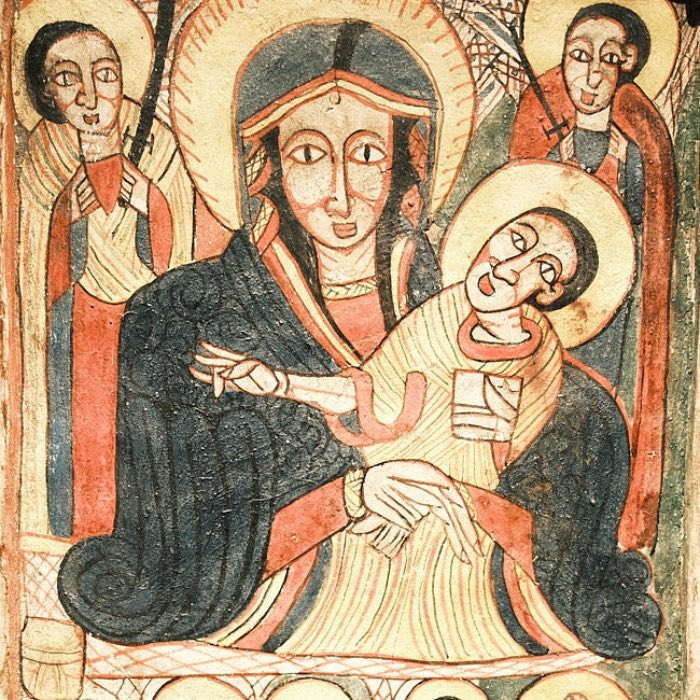

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is one of the oldest Christian traditions in the world, with roots that trace back to the early centuries of Christianity. As the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches, it has played a pivotal role in the religious, cultural, and political life of Ethiopia. Its rich liturgical traditions, distinctive theological perspectives, and unique history reflect a deeply embedded Christian heritage shaped by both local and global influences. When I recently visited Frankfurt, I had the opportunity to explore an exhibition in the Icon Museum showcasing the artistic and spiritual treasures of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. I thought, therefore, it would be fitting to write about the history and significance of this ancient Christian tradition, also as an example of the vast diversity within early Christianity.

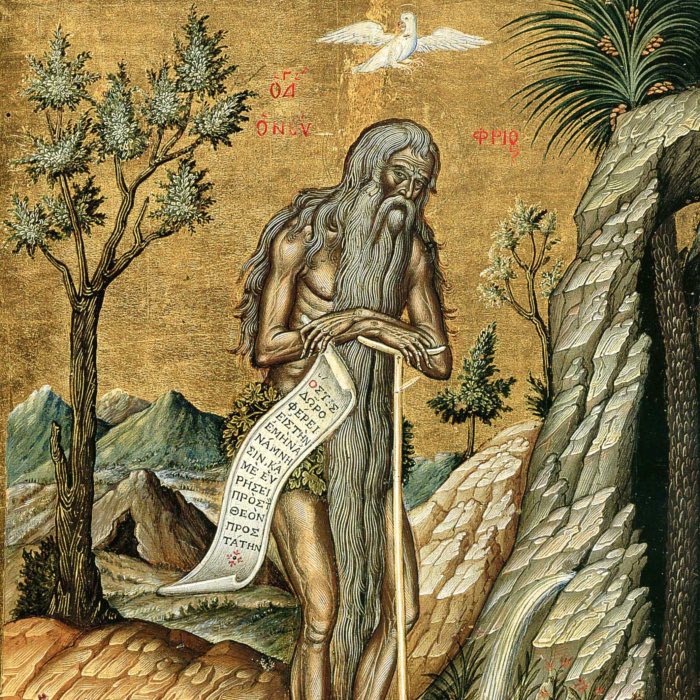

Desert Fathers and the beginnings of Christian monasticism

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics who sought to withdraw from society to live a life devoted to prayer, contemplation, and spiritual discipline. Emerging in the 3rd century CE, primarily in the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, these individuals laid the foundations for Christian monasticism. Their pursuit of a deeper spiritual connection through solitude and meditation mirrors practices found in Buddhist monastic traditions, which also emphasize inner transformation through disciplined contemplation.

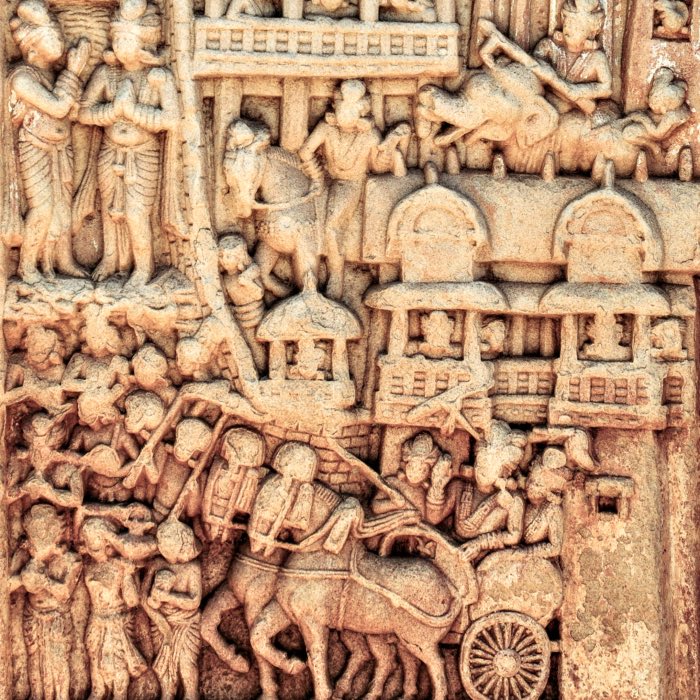

The spread of Greek ideas: Impact on the philosophies, religions, and cultures of the Hellenistic world

The conquests of Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) and the subsequent establishment of Hellenistic successor states created a vast, interconnected empire stretching from Greece to India. This unprecedented geographical and cultural expansion facilitated the diffusion of Greek ideas, institutions, and artistic forms into regions such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indo-Greek kingdoms of Bactria and Gandhara. The resulting cultural exchanges profoundly influenced the philosophical, religious, and cultural landscapes of these regions, blending Hellenistic elements with local traditions to create unique and enduring syntheses.

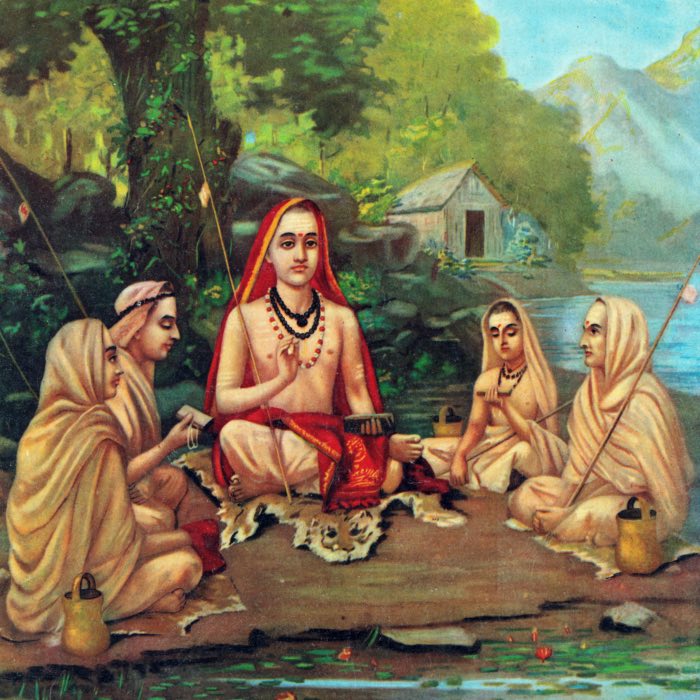

Greek and Indian philosophy: A comparative analysis

Greek and Indian philosophies represent two of the most influential intellectual traditions in human history, both emerging independently but sharing certain common concerns: The nature of reality, the self, ethics, and the path to knowledge and wisdom. Despite arising in distinct cultural contexts, they exhibit parallels in their early developments, as well as significant differences in their metaphysical assumptions, methodologies, and ultimate goals. After exploring both traditions in separate post series, this post compares the development and characteristics of Greek and Indian philosophy, highlighting both their unique trajectories and shared themes.

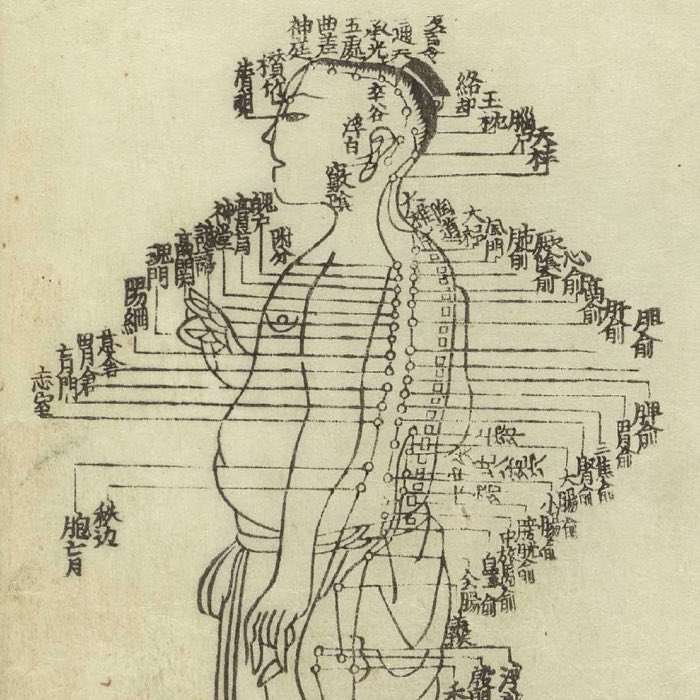

Greek and Chinese philosophy: A comparative analysis

Greek and Chinese philosophy, two of the most influential intellectual traditions in world history, emerged independently in distinct cultural and geographical contexts. Despite their separate origins, both traditions formed the intellectual backbone of their civilizations, fostering growth, prosperity, and a shared cultural identity. They tackled fundamental questions concerning human existence, ethics, politics, and the nature of the cosmos. While Greek philosophy is renowned for its analytical and speculative nature, Chinese philosophy emphasizes practical wisdom and harmonious living. After exploring both traditions in separate post series, this post examines the development, core themes, and characteristics of these two philosophical traditions, highlighting their similarities and unique contributions to human thought.

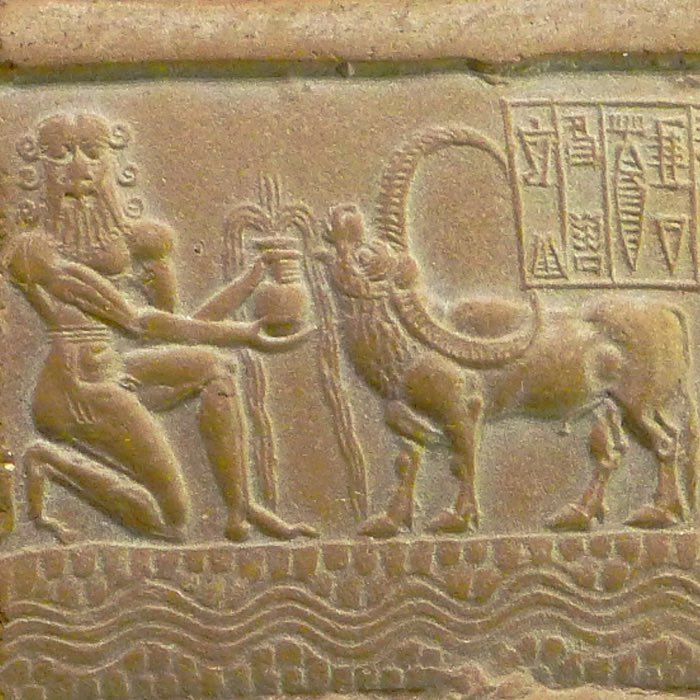

Aphrodite and the interconnections in the ancient world

While Nike and other angel-like figures in Greek mythology seem to have no connections to any Meospotamian deities, there is one goddess whose origins are deeply rooted in the Near East: Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty. Her worship and iconography bear striking resemblances to earlier deities of the region, particularly Inanna-Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. This connection reflects the significant cultural and religious exchanges that shaped early Greek religion, especially during the period of Orientalization in the eighth century BCE.

The emergence of early civilizations – A summary

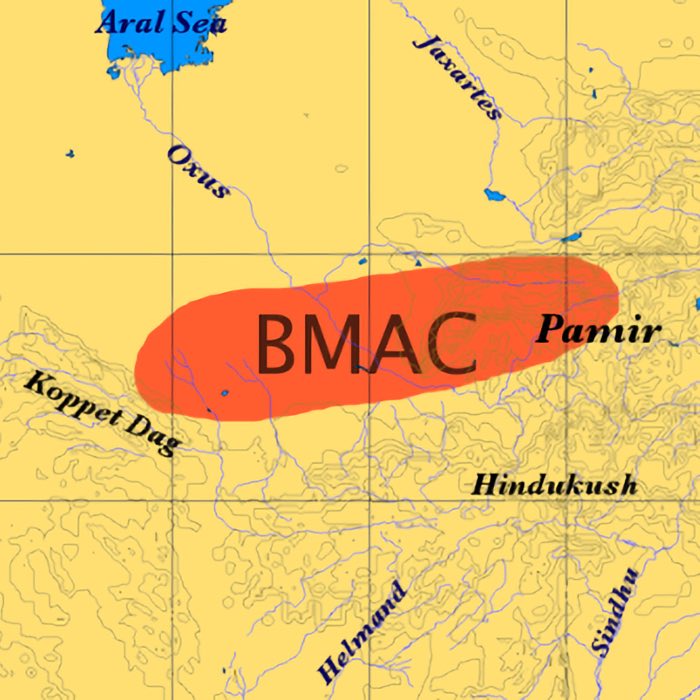

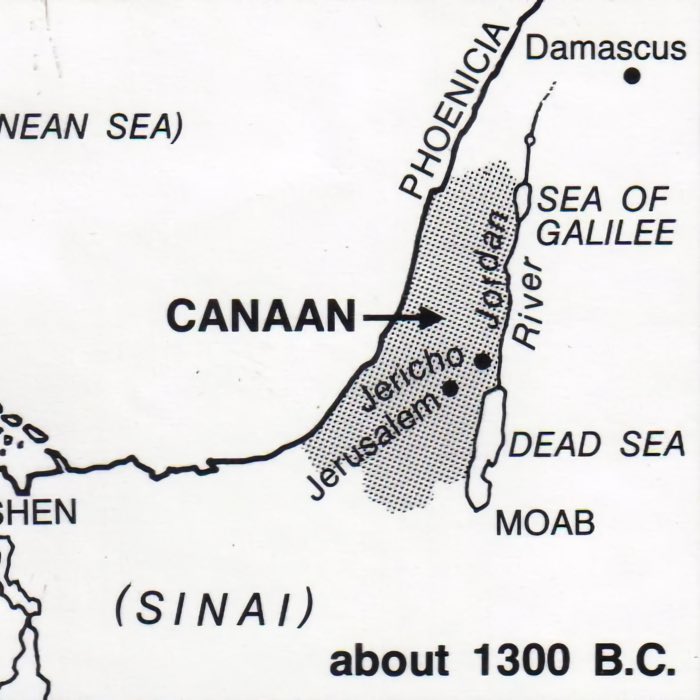

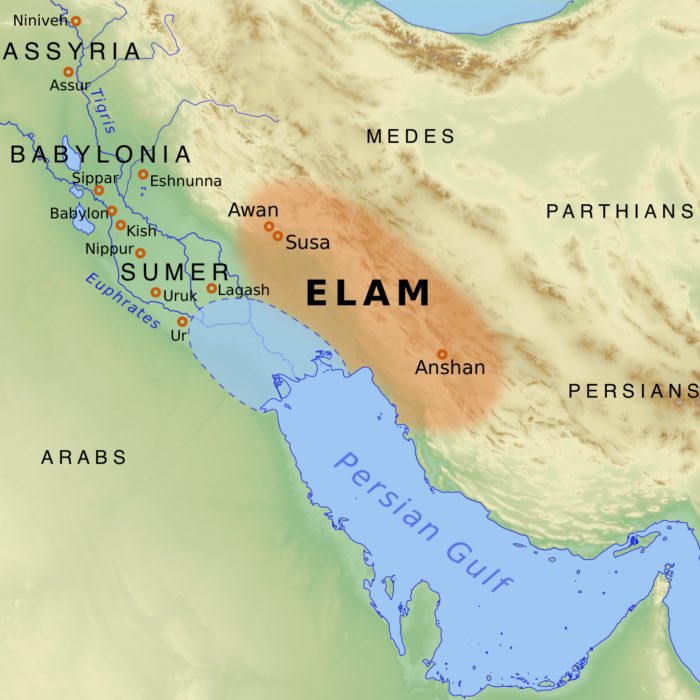

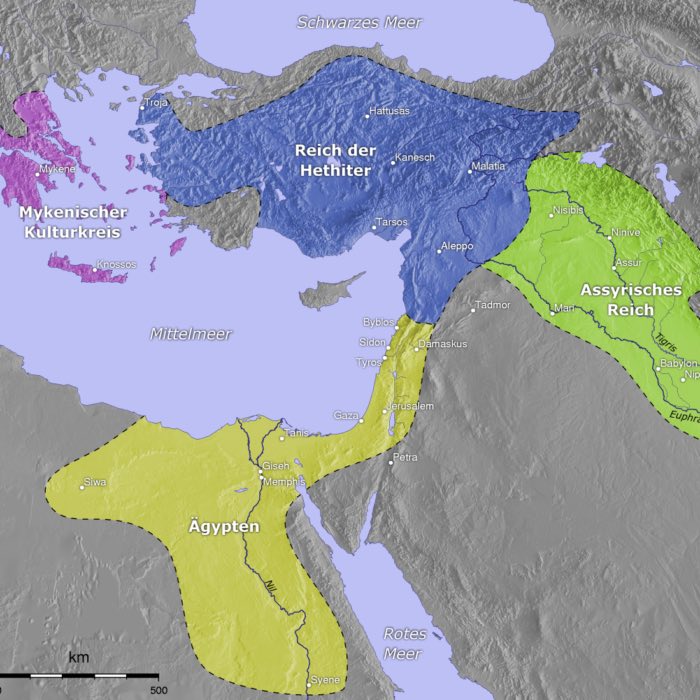

The earliest civilizations in human history represent diverse cultural, geographical, and technological achievements that laid the foundation for modern societies. From the Fertile Crescent to the Andean highlands, these civilizations display remarkable similarities in their pathways to complexity while showcasing unique adaptations to their environments. By examining the civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, India, the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations, the Hittite Empire, the Nok Culture, the Kingdom of Kush, the Canaanite Civilization, the Korean Gojoseon Kingdom, the Jomon Culture of Japan, the Elamite Civilization, the Olmec and Maya civilizations, the Norte Chico civilization, and the Inca Empire, we can discern overarching patterns and distinctive features that defined early human development.

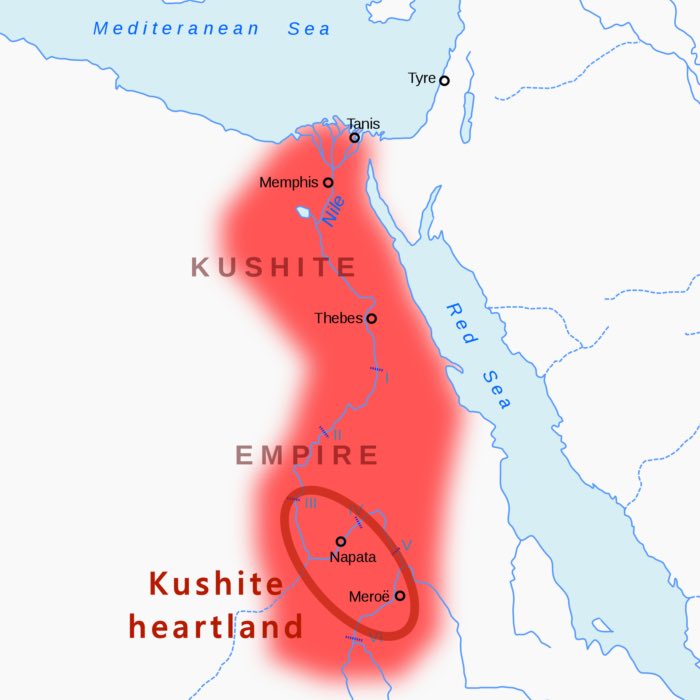

The Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush, flourishing between approximately 1070 BCE and 350 CE, was a major civilization in northeastern Africa, centered in what is now modern-day Sudan. Positioned along the Nile River, Kush played a pivotal role in regional politics, trade, and culture, often interacting with its more famous northern neighbor, Egypt. Renowned for its wealth, monumental architecture, and artistic achievements, the Kingdom of Kush is one of Africa’s great early civilizations, demonstrating the sophistication and interconnectedness of ancient African societies.

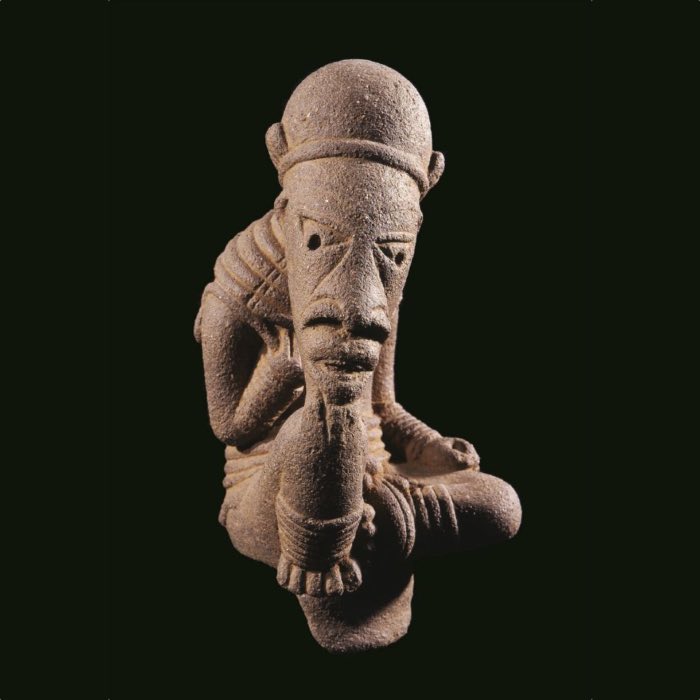

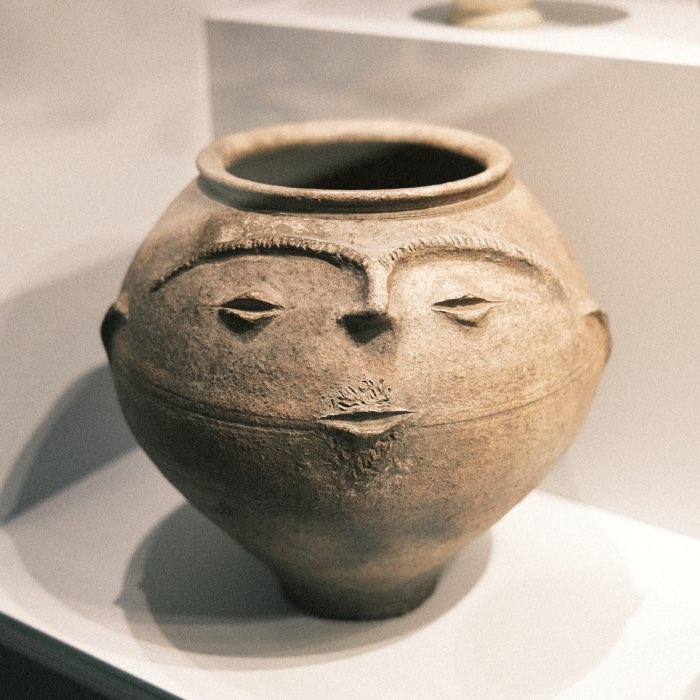

The Nok culture

The Nok culture, flourishing in present-day Nigeria from approximately 1000 BCE to 300 CE, is one of the earliest known complex societies in sub-Saharan Africa. Renowned for its distinctive terracotta sculptures and early ironworking, the Nok culture represents a significant chapter in African history. Its cultural and technological achievements influenced later West African civilizations, laying the foundation for complex societies in the region.

The emergence of civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt: A comparative analysis

The emergence of civilization represents a pivotal moment in human history, marked by the development of complex social structures, organized governance, technological advancements, and the establishment of cultural norms that would define human society for millennia. Two regions that epitomize this transformative era are Mesopotamia, located in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and Egypt, centered around the life-sustaining Nile River. Despite distinct geographical and cultural contexts, both regions independently developed advanced civilizations that laid the groundwork for human progress while also engaging in cross-cultural interactions.

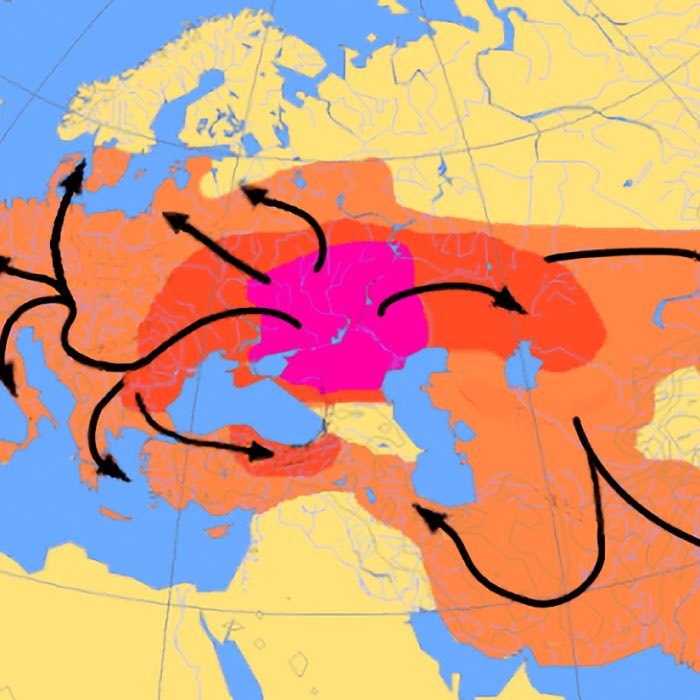

The 'Out of Africa' theory: Humanity's origins and dispersal

The Out of Africa theory (OOA) is one of the most widely accepted models explaining the origins and global dispersal of modern Homo sapiens. Rooted in archaeological, genetic, and paleoanthropological evidence, this theory posits that modern humans first evolved in Africa before migrating to other parts of the world. This migration set the stage for the diversity and complexity of human societies, eventually leading to the development of civilizations.

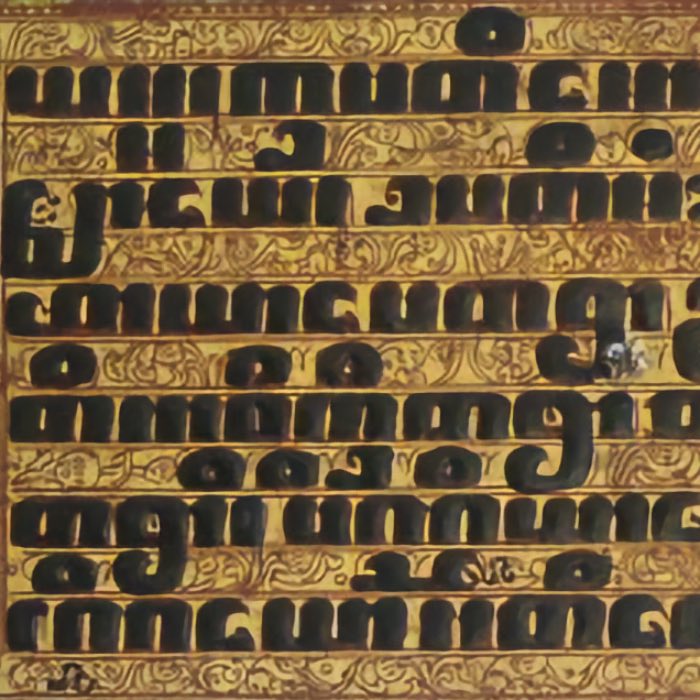

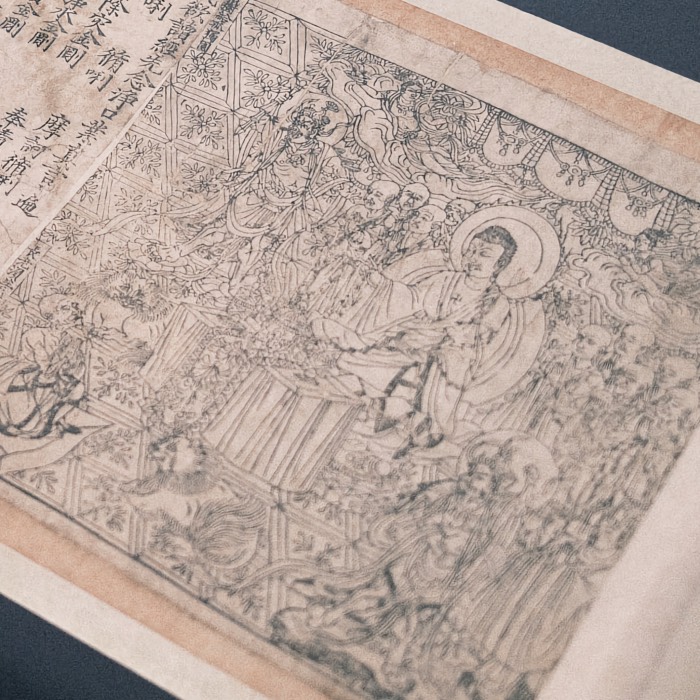

A brief history of writing

I believe, that writing is one of the most significant inventions in human history, playing a crucial role in the development and success of civilizations. From ancient pictographs to modern alphabets, writing has enabled the recording and dissemination of knowledge, fostering communication, culture, and governance. In this article, we therefore briefly explore the history of writing, tracing its origins in various ancient civilizations and highlighting its profound impact on human progress.

#American Culture

Christianity's death toll

The institutions of the Christianity has played a central role in shaping Western history for nearly two millennia, influencing political, social, and cultural developments on a global scale. Alongside its contributions to art, education, and social welfare, the Christianity has also been a catalyst for some of history’s most violent and destructive events. From the Crusades and inquisitions to pogroms and forced conversions, these actions have resulted in untold suffering and loss of life. This post seeks to critically examine the death tolls associated with Christianity’s direct and indirect actions, placing them within their historical contexts and exploring the moral and ethical implications of such a legacy.

The ethnocide of native American children in Canada by Catholic residential schools

The legacy of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools is one of profound suffering, cultural annihilation, and the enduring consequences of systemic ethnocide. Operated primarily by Christian organizations, including the Catholic Church, these institutions were designed to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society, erasing their languages, traditions, and spiritual beliefs. The discovery of unmarked graves at sites like Kamloops Indian Residential School in 2021 has brought renewed scrutiny to this dark chapter in Canadian history and exposed the devastating role of religious institutions in perpetuating harm under the guise of education and salvation.

The Black Holocaust and the complicity of the Catholic Church

The Black Holocaust represents one of the most prolonged and devastating human atrocities in history. It encompasses the mass enslavement, exploitation, and extermination of African people, particularly through the Trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Atlantic slave trades. This prolonged system of oppression did not end with slavery’s formal abolition but continued through colonialism, imperialism, systemic racism, and the economic disenfranchisement of African and African-descendant populations worldwide. Central to this system was the role of the Catholic Church, which not only provided theological justification for the enslavement of Africans but also materially benefitted from it. Papal decrees facilitated European expansion and the trade of enslaved persons, while Church institutions engaged in and profited from slavery. Even after abolition, the Church was slow to confront its moral culpability, and its complicity remains a subject of historical reckoning.

The genocide in South America and the role of the Catholic Church

The colonization of South America by European powers in the 15th and 16th centuries marked one of the darkest chapters in human history. Under the guise of spreading Christianity, European conquerors and missionaries orchestrated a devastating conquest that annihilated entire cultures, subjugated indigenous populations, and caused the deaths of millions. The Spanish and Portuguese empires, often with the active support and encouragement of the Catholic Church, framed this colonization as both a civilizing mission and a divine mandate. However, the resulting destruction starkly contradicts Christian core teachings, which emphasize love, humility, and compassion. The genocide in South America, as some historians have termed it, was not merely the product of imperial greed but also of religious dogma weaponized to legitimize conquest and violence.

The Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, known as Tawantinsuyu in Quechua, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America, flourishing between the 15th and early 16th centuries CE. Centered in the Andean highlands of South America, the empire extended across present-day Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina. Renowned for its advanced infrastructure, administrative organization, and cultural achievements, the Inca Empire represents the pinnacle of Andean civilization. Its legacy continues to influence modern Andean cultures.

The Norte Chico civilization

The Norte Chico civilization, also known as the Caral-Supe civilization, is one of the oldest known complex societies in the Americas. Flourishing between approximately 3000 BCE and 1800 BCE along the arid coast of modern-day Peru, Norte Chico represents an early cradle of civilization in the New World. Distinguished by monumental architecture, complex societal organization, and a reliance on maritime and agricultural resources, it predates more widely known Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations like the Maya and Inca.

The Maya civilization

The Maya civilization, which flourished between approximately 2000 BCE and 1500 CE, represents one of the most sophisticated and enduring cultures of the ancient Americas. Centered in the tropical lowlands of present-day Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, and southern Mexico, the Maya are renowned for their achievements in writing, astronomy, mathematics, and monumental architecture. The civilization’s intricate socio-political structures and vibrant cultural traditions continue to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike.

The Olmec civilization

The Olmec civilization, often referred to as the ‘mother culture’ of Mesoamerica, flourished in the Gulf Coast region of present-day Mexico between approximately 1500 BCE and 400 BCE. Renowned for their monumental stone heads, intricate art, and foundational cultural contributions, the Olmecs set the stage for subsequent civilizations such as the Maya and Aztecs. Their influence extended far beyond their geographic boundaries, leaving an enduring legacy in Mesoamerican religion, architecture, and societal organization.

A brief history of writing

I believe, that writing is one of the most significant inventions in human history, playing a crucial role in the development and success of civilizations. From ancient pictographs to modern alphabets, writing has enabled the recording and dissemination of knowledge, fostering communication, culture, and governance. In this article, we therefore briefly explore the history of writing, tracing its origins in various ancient civilizations and highlighting its profound impact on human progress.

#Ancient Times

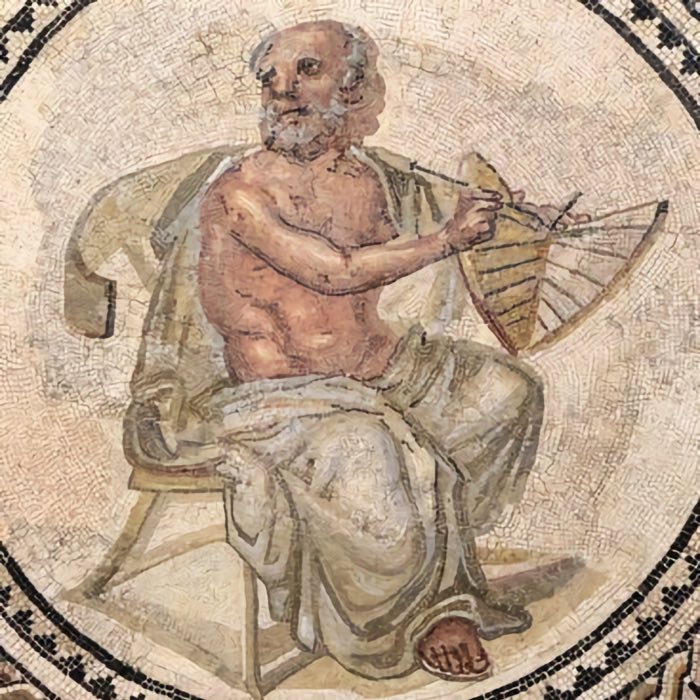

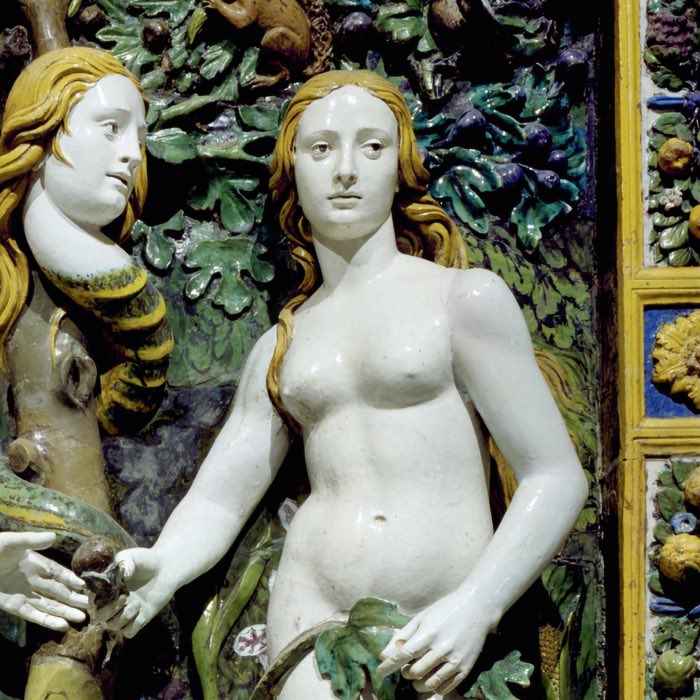

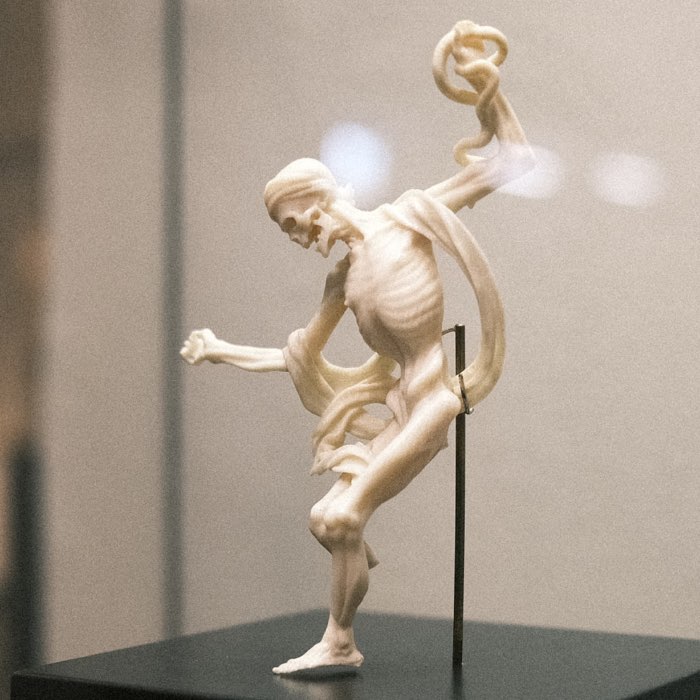

Ancient sculptures in color: Revisiting Greek and Roman polychromy

For centuries, the prevailing image of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture has been one of pure white marble, stripped of any decorative elements or applied colors. This perception is still widespread today, shaping how the European classical world is imagined in museums, schoolbooks, and popular culture. Yet this idea is fundamentally misleading. During my recent visit to the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung in Frankfurt, the exhibition Bunte Götter (‘Painted Gods’) offered a striking correction to this misconception. Based on decades of research into the original polychromy of ancient sculpture, the exhibition highlights both the scientific findings and the ideological roots of the ‘white marble myth’. Here are some impressions and insights I collected during my visit.

Jewish life under Islamic rule

The history of Jewish communities under Islamic rule presents a complex interplay of coexistence, cultural flourishing, and occasional hardship. Compared to their experiences in Christian Europe during the same period, Jewish life under Islamic governance was often marked by relative tolerance and integration, though not without challenges. This is particularly evident in Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), where cities like Córdoba, Toledo, and Granada became vibrant centers of Jewish cultural and intellectual life. This unique interplay of Islamic legal principles, political pragmatism, and cultural exchange provided an environment that, while not devoid of discrimination, allowed Jewish communities to thrive in unprecedented ways.

Pope Leo I: The architect of papal primacy and the foundations of Roman Christianity

Pope Leo I, known as Leo the Great (r. 440–461 CE), played a transformative role in shaping the self-identity of the Catholic Church and the role of the papacy. His pontificate came at a pivotal moment in the history of Christianity, as the Roman Empire faced profound crises, both internal and external. Leo’s theological contributions, political actions, and strategic emphasis on the centrality of the Bishop of Rome not only elevated the papacy’s authority but also laid the groundwork for the institutional Church’s consolidation of power. This post examines how Leo’s assertions of temporal and spiritual authority, his theological framing of Peter and Paul, and his role in defining Roman Christianity set the stage for the papacy’s influence and the Church’s evolving relationship with political power.

How the Pope in Rome became the arbiter of imperial legitimacy

The shift from the Roman Senate to the Pope in Rome as the arbiter of imperial legitimacy reflects a profound transformation in the political and spiritual dynamics of Europe. This evolution unfolded over centuries, shaped by the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the reorganization of power in the post-Roman world, and the eventual fusion of Christian and imperial authority under Charlemagne. In this post, we explore the circumstances under which the Pope in Rome assumed the role of crowning emperors, the status of imperial authority during the period between the fall of Rome and Charlemagne, and the fate of emperors after Charlemagne’s coronation.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire and the role of Christianity during the Migration Period

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE and the subsequent migration and settlement of Germanic and Gothic peoples marked a transformative period in European history. While these events often evoke images of chaos and decline, they also created fertile conditions for the spread of Christianity. Far from being a passive beneficiary, Christianity actively adapted to and shaped the political and cultural dynamics of the post-Roman world. The religion’s message, institutional flexibility, and ability to integrate with existing social and political structures enabled it to thrive among the migrating peoples, ultimately becoming the unifying spiritual framework of medieval Europe. This post examines the relationship between the migration of peoples, the fall of the Western empire, and the spread of Christianity, focusing on its adoption by Germanic and Gothic kings and their inhabitants, culminating in Charlemagne’s Christian empire. We explore how the disruptions of Late Antiquity contributed to Christianity’s ascendancy as both a religious and political force.

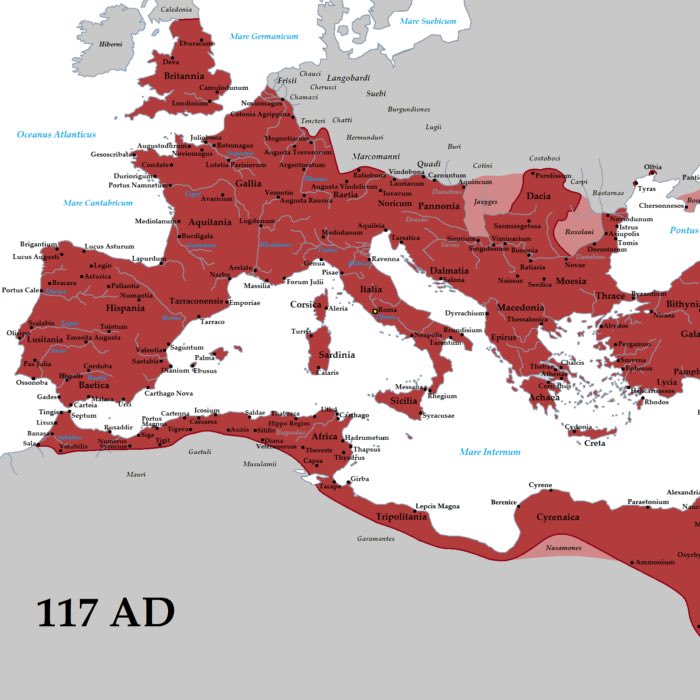

How the Roman Empire laid the foundations for Western civilization

The Roman Empire stands as one of the most influential civilizations in history, leaving a profound legacy that continues to shape modern society. From groundbreaking innovations in infrastructure and engineering to advancements in governance, education, and science, the Romans demonstrated an unparalleled ability to adapt and expand upon the knowledge of other cultures. Their achievements not only transformed the ancient world but also laid critical foundations for the development of Western civilization. In this post, we explore the civilizational and scientific developments introduced or disseminated by the Romans, whether original inventions, adaptations, or further enhancements, showcasing how their contributions have endured through time.

The destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria in 391 CE: Christianity's shift from persecuted to persecutor

The destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria in 391 CE stands as one of the most emblematic events of Late Antiquity, symbolizing the dramatic transformation of Christianity from a persecuted minority to an institution wielding the power of the Roman state. This episode not only marked the decline of pagan religious practices in Alexandria but also reflected the broader social, political, and theological shifts that had accompanied the rise of Christianity as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. The destruction of this magnificent temple dedicated to the Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis offers profound insights into the dynamics of religious conflict, the role of Church authorities, and the consequences of imperial policies aimed at religious consolidation.

The Constantinian Turn: Myth, reality, and its implications for Christianity

The ‘Constantinian Turn’ refers to the moment when Emperor Constantine the Great supposedly converted to Christianity and ushered in a new era of state-sponsored Christian dominance. This event is often portrayed as the turning point when Christianity transitioned from a persecuted minority religion to the dominant faith of the Roman Empire. However, the historicity of Constantine’s dramatic conversion story — centered on the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312) and his subsequent vision of the cross — has been increasingly scrutinized by modern scholars. In this post, we examine the current state of research regarding the alleged Constantinian Turn, highlighting discrepancies between archaeological evidence and church chronicles. We also explore what this event, whether historically accurate or not, reveals about the Church’s evolution, particularly its association with imperial power, violence, and values that contradict the very core teachings of Christianity.

Is Christianity the most engineered religion in history?

The question in the title of this post is of course ironic. Every religion is a construct that evolves over time, adapting to the cultural, social, and political circumstances of its adherents. Religions are shaped by their historical contexts, assimilating ideas and practices to remain relevant. However, Christianity stands out for its systematic appropriation of Greco-Roman philosophical concepts and Jewish traditions to form a comprehensive theological framework. In this post, we (provocatively) explore how Christianity, often perceived as a divine revelation, is deeply rooted in Greco-Roman philosophy and Jewish apocalyptic ideas. We further examine which elements of Christian theology are uniquely Jewish or Christian, contrasting them with their Greco-Roman counterparts.

From YHWH to God: How Greek philosophy shaped Jewish and Christian perception of the Absolute

The transformation of the concept of God in both Judaism and Christianity is one of the most profound developments in religious history. From the anthropomorphic and personal YHWH of the Hebrew Bible to the abstract, infinite, and ineffable deity central to Christian theology and later Rabbinic Judaism, this evolution was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy. Particularly during the Hellenistic period and beyond, ideas from Platonism, Stoicism, and Neoplatonism provided a conceptual framework that reshaped the understanding of divinity in both traditions. In this post, we explore how Greek philosophical thought transformed the perception of God in Judaism and Christianity, with emphasis on their shared roots and divergent developments.

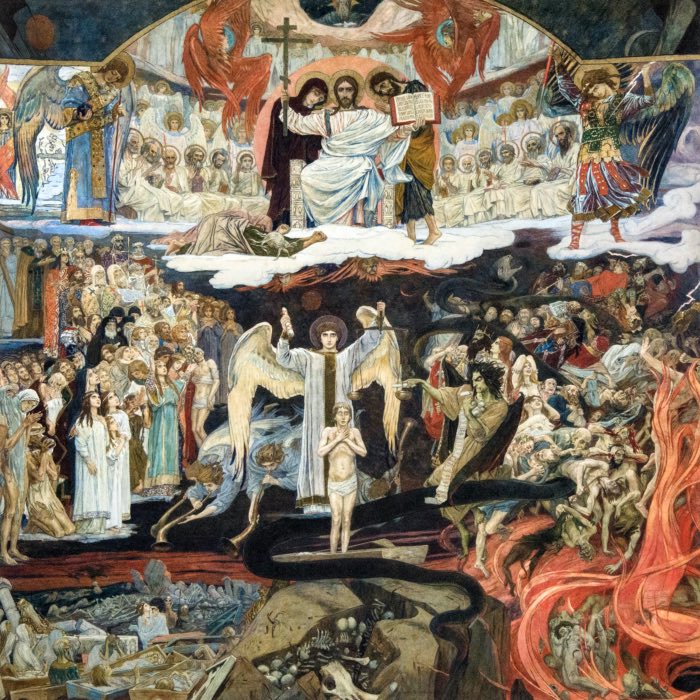

Theosis: An alternative view of hell, evil, and salvation in Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodox Christianity presents a unique theological perspective that diverges in significant ways from Western Christian traditions. Among these differences are the understanding of hell, evil, and the ultimate purpose of human life. While the Western Church often conceptualizes hell as a place of punitive suffering and views salvation as a juridical resolution to sin, Eastern Orthodoxy frames these ideas within a more relational and mystical context, emphasizing theosis — the union of humanity with the divine. In this post, we explore these theological differences by focusing on the Orthodox views of hell, evil, and the concept of theosis as an transformative process.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is one of the oldest Christian traditions in the world, with roots that trace back to the early centuries of Christianity. As the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches, it has played a pivotal role in the religious, cultural, and political life of Ethiopia. Its rich liturgical traditions, distinctive theological perspectives, and unique history reflect a deeply embedded Christian heritage shaped by both local and global influences. When I recently visited Frankfurt, I had the opportunity to explore an exhibition in the Icon Museum showcasing the artistic and spiritual treasures of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. I thought, therefore, it would be fitting to write about the history and significance of this ancient Christian tradition, also as an example of the vast diversity within early Christianity.

Shestodnev icons: The six-day work of God

The Shestodnev (Six-Day) icon emerged in the late 15th century, embodying a theological synthesis of the biblical narrative of creation and the liturgical rhythms of Christian worship. Its development coincided with the eschatological concerns of the era, particularly as the year 1492 – believed to mark 7,000 years since the creation of the world – drew near. At this time, many Christians sought to comprehend not only their personal salvation but also the divine economy guiding humanity and the Church’s role within it. The Shestodnev icon became a visual testament to these inquiries, combining symbolic representations of Genesis, sacred history, and the liturgical week.

Isaak Demetrakes' Heavenly and Earthly Jerusalem: A masterpiece of orthodox iconography

The Heavenly and Earthly Jerusalem Icon, attributed to Isaak Demetrakes and housed in the Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt, is a remarkable and intricate representation of Christian eschatology and salvation history. With its detailed visual theology, it stands for the the power of iconography in Orthodox Christianity to convey complex narratives. In this post, we will take a detailed look at the icon’s structure and try to understand its theological and artistic significance.

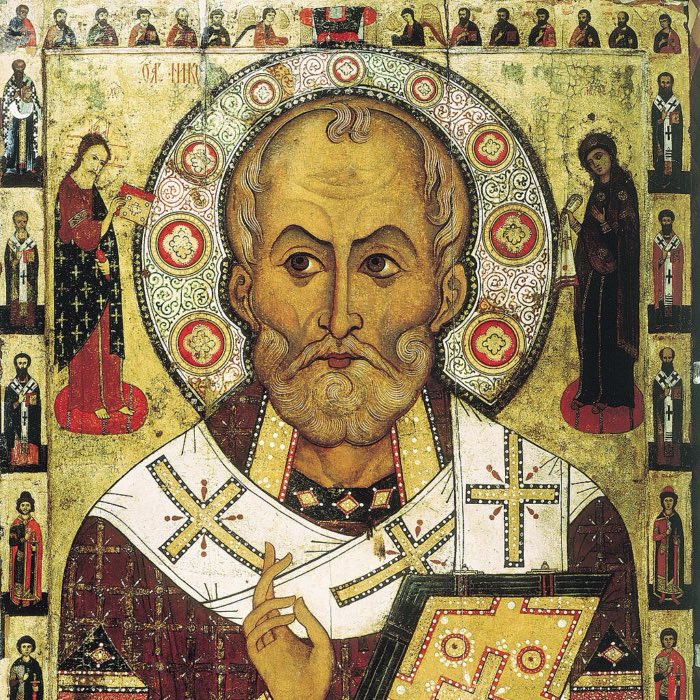

The role of icons in Orthodox believes

Orthodox icons, derived from the Greek word eikṓn meaning ‘image’ or ‘likeness’, play a foundational role in the faith, theology, and worship of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Far from being decorative objects, icons are viewed as sacred tools of devotion, offering believers a tangible connection to the divine. Often described as ‘windows to heaven’, icons serve as both theological affirmations and personal aids in spiritual practice. Their rich history, theological significance, and symbolic artistry distinguish them from other forms of Christian art, underscoring their profound role in Orthodox beliefs. I recently visited the Icon Museum in Frankfurt, where I had the opportunity to explore and appreciate original Orthodox icons.

Desert Fathers and the beginnings of Christian monasticism

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics who sought to withdraw from society to live a life devoted to prayer, contemplation, and spiritual discipline. Emerging in the 3rd century CE, primarily in the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, these individuals laid the foundations for Christian monasticism. Their pursuit of a deeper spiritual connection through solitude and meditation mirrors practices found in Buddhist monastic traditions, which also emphasize inner transformation through disciplined contemplation.

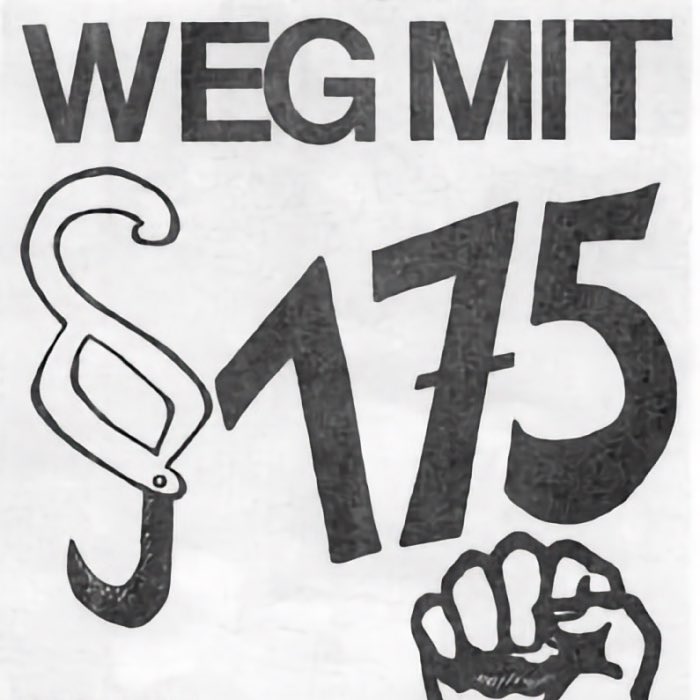

Homosexuality in Christian history: Persecution and moral condemnation

Throughout history, the Christian Church has played a significant role in shaping societal attitudes toward sexuality, including homosexuality. The Church’s stance on homosexuality has evolved over time, influenced by theological interpretations, cultural contexts, and legal frameworks. This article explores the historical relationship between the Church and homosexuality, examining key events, doctrines, and societal impacts from early Christianity to the modern era.

Dogma and its role in Christian orthodoxy

The term dogma originates from the Hellenistic philosophical tradition, where it denoted a central tenet or principle held to be authoritative within a given school of thought, such as Stoicism or Epicureanism. In these contexts, dogma referred to reasoned conclusions about nature, ethics, or metaphysics, rooted in dialogue and philosophical inquiry. However, as Christianity adopted and adapted the term, it evolved into a rigid tool of religious authority.

Contra Celsum: Origen's response and the irony of survival

The work Contra Celsum (Against Celsus) by Origen of Alexandria is a landmark in early Christian apologetics. Written in the late 2nd or early 3rd century CE, it serves as a detailed rebuttal to the criticisms of Christianity put forward by Celsus, a 2nd-century Greek philosopher. While Origen’s aim was to defend the faith and refute Celsus’ arguments, the ironic legacy of Contra Celsum is that it preserved, almost in its entirety, the very criticisms it sought to dismantle. Celsus’ original work, The True Doctrine, has been lost to history, and modern scholars rely almost entirely on Origen’s quotations to reconstruct its content. In this post, we examine Contra Celsum in its historical context, explore Origen’s counterarguments to Celsus’ criticisms, and reflect on the unintended consequences of Origen’s efforts. This irony reveals much about the early development of Christian thought, the nature of religious polemics, and the preservation of intellectual discourse in antiquity.

The fututor of Carnuntum: Homosexuality in the Roman Empire

The discovery of an enigmatic tombstone in Carnuntum, an important Roman city on the Danube frontier, has sparked scholarly debate regarding its possible implications for understanding same-sex relationships in the Roman world. The inscription, attributed to Lucius Julius Faustus in honor of Lucius Julius Optatus, a physician, contains the puzzling term fututor, a word that classically refers to someone engaged in sexual activity. The presence of such a term on a funerary inscription is highly unusual, prompting speculation about the nature of the relationship between these two men. In this post, we briefly discuss homosexuality in the Roman Empire in general and explore the possible interpretations of the Carnuntum inscription.

Roman amulet found in Nida changes history of early Christianity north of the Alps

The recent discovery of a Christian amulet in a cemetery near the site of Roman Nida, now part of Frankfurt-Heddernheim, has provided new and compelling evidence about the spread of Christianity in the Roman provinces north of the Alps. Unearthed during ongoing archaeological investigations, the artifact, estimated to date to between 230 and 270 CE, represents the earliest known material evidence of Christian presence in this region. This finding is not only an archaeological sensation but also a pivotal moment in revising our understanding of how and when Christianity reached the outer provinces of the Roman Empire.

Nida: A glimpse into Roman provincial life

During a recent visit to the Frankfurt, I had the opportunity to explore the Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt and its impressive collection of artifacts from the Roman city of Nida. As I wandered through the museum’s galleries, I was struck by the tangible connection to the Roman past that Nida represented. This vicus, located in the modern Frankfurt-Heddernheim district, offered an intricate view of daily life, trade, and cultural exchange within the Roman province of Germania Superior. The museum’s exhibits, ranging from pottery and coins to architectural fragments and religious artifacts, provided an immersive experience of a settlement that, though often overshadowed by larger Roman cities, played a significant role in the region’s development. In this post, I’d like to share some insights into the historical and archaeological significance of Nida, along with some photos from my visit to the museum.

The cult of Mithras and Roman mystery religions: Christianity in a spiritual melting pot

The Roman Empire was a diverse and dynamic society, characterized by a remarkable degree of cultural and religious plurality. Its vast territory, encompassing a multitude of ethnic groups, languages, and traditions, became a fertile ground for the emergence and spread of new spiritual movements and mystery cults. Among these, the cult of Mithras stands out as one of the most enigmatic and influential. Christianity, which eventually rose to dominance within this pluralistic environment, potentially shares some overlaps with these contemporary religious traditions. In this post, we take a closer look at the cult of Mithras and its place within the spiritual landscape of the Roman Empire.

Faith or order? The true reasons behind Roman persecution of Christians

The perception of Christian persecution in the Roman Empire often evokes images of unwavering believers suffering gruesome punishments for their faith. However, the reality is far more complex and nuanced. Contrary to popular belief, Christians were not primarily persecuted for their religious doctrines or beliefs. Instead, the Roman authorities’ actions stemmed largely from legal, social, and political concerns, with religion playing a secondary role. In this post, we explore the multifaceted reasons behind the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire and shed light on the broader context in which these events unfolded.

Is Christianity a polytheistic religion?

Christianity is widely regarded as the paragon of monotheism, standing alongside Judaism and Islam as one of the so-called Abrahamic faiths. This perception, however, demands scrutiny. While Christian theology insists on the worship of a singular, all-powerful God, its historical development and ritualistic practices reveal a cosmos teeming with divine and semi-divine figures. These figures are venerated across cultures and epochs in ways that resemble pre-Christian polytheistic traditions. Christianity, it seems, may not be as monotheistic as it claims to be.

Mother of God cult in the Roman empire and its transformation into Marian devotion

The veneration of Mary, the proclaimed Mother of Jesus, holds a central place in Christianity today, but its development is deeply rooted in the religious and cultural traditions of the Roman Empire. Far from being a concept that emerged fully formed, the cult of Mary evolved gradually, shaped by both theological debates within early Christianity and the broader cultural influences of maternal archetypes from Greco-Roman religions. This synthesis allowed Christianity to appeal to a diverse audience in a pluralistic empire while providing continuity for converts from other faiths. This post explores the origins, development, and significance of Marian devotion, focusing on how it emerged from and transformed existing traditions.

Earliest depictions of Jesus

The visual representation of Jesus has undergone significant evolution over centuries, reflecting shifts in theological emphasis, political messages, cultural influences, and artistic traditions. The earliest depictions are a blend of simplicity, symbolic abstraction, and borrowing from contemporary artistic conventions. These images provide a fascinating insight into the lives and beliefs of early Christian communities and the ways they sought to express their faith visually.

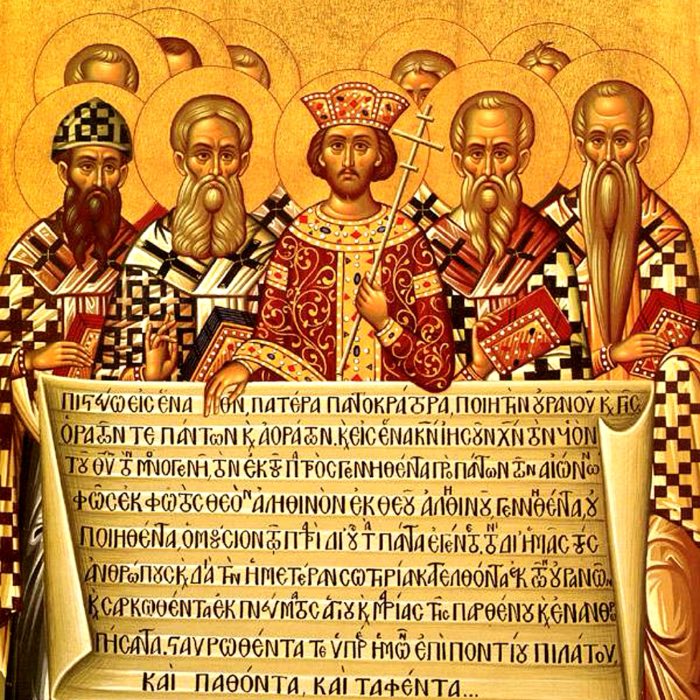

First Council of Nicaea and the political construction of the Nicene Creed

The First Council of Nicaea, convened in 325 CE by Emperor Constantine I, has long been heralded as a watershed moment in Christian history, shaping the theological framework of the religion for centuries to come. Often portrayed as a council addressing spiritual unity and doctrinal clarity, a closer examination reveals its primary motivations were far from purely spiritual. Instead, the council served as a political instrument to consolidate power, define orthodoxy, and exclude opposing interpretations within the burgeoning Christian movement. Central to this effort was the formulation of the Nicene Creed, a declaration of faith that entrenched the doctrine of the Trinity — an artificial construct that served as a boundary marker rather than a reflection of spiritual revelation. In this post, we explore the political context of the Nicene Council and how the Nicene Creed was crafted as a tool of ecclesiastical and imperial authority, rather than a genuine expression of divine truth.

Trinity: An example of how Christianity engineered itself beyond its original scriptures

The doctrine of the Trinity, one of the central tenets of mainstream Christian theology, posits that God exists as three coequal and coeternal persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. However, when we examine the earliest Christian writings — particularly the epistles of Paul — we find little evidence that this doctrine was part of early Christian belief. Instead, it appears to have developed over several centuries through a complex process of theological debate, doctrinal evolution, and ecclesiastical consolidation. In this post, we explore how the concept of the Trinity was absent from Paul’s theology, how later Christian doctrines were shaped through reinterpretation, textual alteration, and even forgery, and how crucial elements of what we now consider core Christian beliefs were defined long after the earliest Christian communities.

The birth of Christian priesthood and hierarchical structures: From egalitarian communities to institutionalized religion

The establishment of a formal priesthood and hierarchical structures in Christianity marked a significant departure from the original ethos of the Jesus movement. In its earliest days, the Jesus community operated as a loosely organized and egalitarian network of believers, emphasizing mutual support, shared leadership, and spiritual equality. Over time, however, as the movement expanded, it adopted increasingly formalized structures of leadership and worship. This evolution was influenced not only by internal needs for organization and authority but also by the cultural and religious environment of the Roman Empire.

The Didache: The blueprint of a developing church and the birth of ritualized Christianity

The Didache (Teaching of the Twelve Apostles), one of the earliest Christian texts outside the New Testament, provides a fascinating glimpse into the practices and beliefs of the early Jesus movement. Likely written in the late first or early second century CE, this text serves as a manual for Christian communities, covering topics such as ethics, baptism, the Eucharist, and church organization. While it sheds light on the simplicity of early Christian life, it also reveals the early emergence of ritualized and hierarchical structures that would later define the institutional Church.

How much does Christianity actually differ from Judaism?

The relationship between Christianity and Judaism has been a topic of theological, historical, and cultural debate for centuries. While Christianity is often perceived as a distinct religion with unique beliefs, practices, and institutions, a deeper analysis reveals that Christianity is deeply rooted in Judaism, to the point that it might be better understood as a Jewish sect that evolved under specific historical conditions. This post examines Christianity’s foundational elements — its theology, scriptures, ethics, rituals, and symbolism — and argues that Christianity is inherently Jewish, with some meaningful divergence from its parent tradition.

Why Jews did not believe in Jesus: Historical and theological roots of the Jewish-Christian divergence

The emergence of Christianity in the first century CE as a distinct movement within Judaism raises fundamental questions about why the majority of Jews did not accept the figure of Jesus of Nazareth as the long-awaited Messiah. The reasons are rooted in the theological, sociopolitical, and cultural contexts of the time, as well as differing interpretations of messianic expectations. In this post, we briefly examine the historical and religious landscape of Second Temple Judaism, the nature of Jewish messianic hope, and the ways in which early Christian beliefs conflicted with those expectations, ultimately leading to the divergence between Judaism and Christianity.

The Apostolic Council: A turning point in the expansion of early Christianity

The Apostolic Council, often referred to as the Council of Jerusalem, was a pivotal moment in the history of Christianity. Held around 48–50 CE, this gathering addressed a critical question: Could non-Jews, or Gentiles, join the community of Jesus’ followers without first converting to Judaism? This decision marked a decisive shift, transforming the Jesus movement from a Jewish sect into a universal faith accessible to all people. The outcomes of this meeting not only facilitated the rapid expansion of early Christianity but also fundamentally reshaped its identity and relationship with Judaism.

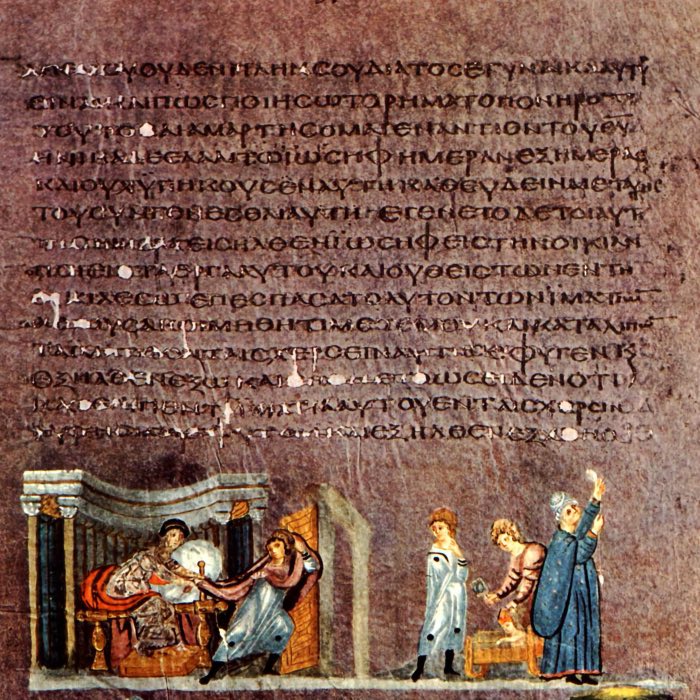

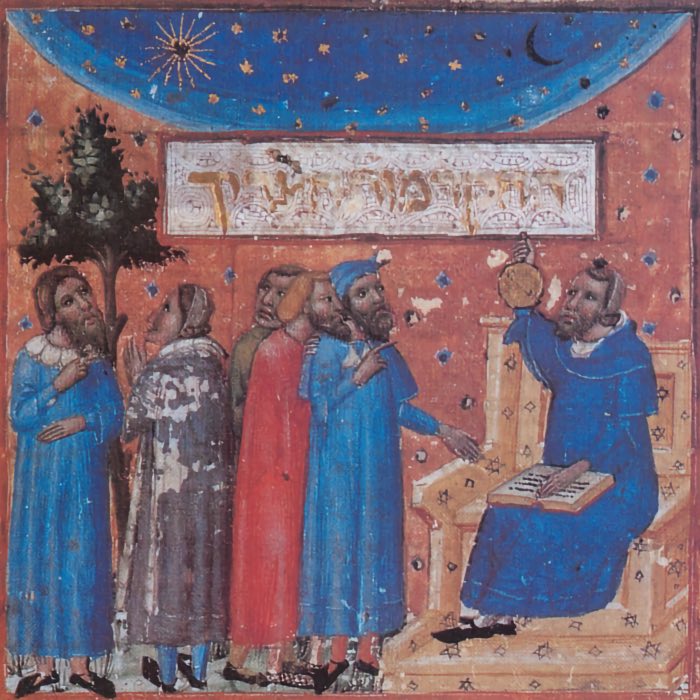

Dura-Europos: One of the earliest Christian house churches and oldest synagogues in a religious melting pot

The house church and synagogue at Dura-Europos, an ancient city on the Euphrates River in modern-day Syria, offer unique insights into the coexistence and evolution of early Christian and Jewish communities. Dating to the mid-3rd century CE, these structures are among the oldest known dedicated spaces for Christian and Jewish worship. Their simultaneous presence within the same urban setting – along with temples dedicated to Greco-Roman, Palmyrene, and local Mesopotamian deities – illustrates the intertwined histories of Judaism and Christianity, highlighting a time when these faiths developed side by side before Christianity emerged as a dominant religion within the Roman world.

The life and practices of early Christians

The early Christians community developed in the decades following the emergence of beliefs about Jesus as the Messiah. This period was marked by efforts to define their practices and theology while navigating their place within both Jewish traditions and the broader Greco-Roman world. This article explores the life, practices, and self-perception of these early communities based on the current state of research.

The spread of early Christianity

The emergence and spread of Christianity is one of the most significant transformations in human history. Rooted in Jewish apocalyptic expectations, early Christianity evolved into a universal religion that transcended its origins. Central to this transformation were historical figures such as Paul of Tarsus and the networks of early Christian communities throughout the Roman Empire. In this post, we examine the historical development of early Christianity, focusing on its dissemination, the role of key figures, and the cultural and social dynamics that facilitated its spread.

Did Jesus' teachings shape the apostolic missions? A theological exploration

The question of whether the theological constructs attributed to Jesus were primarily perceived as a message about the imminent end of the world — and whether this perception shaped the apostolic missions — invites a closer look at the early Christian movement. In this post, we examine the historical and theological context of these attributed teachings, the role of apocalypticism in early Christianity, and the adaptability of the Gospel message over time.

The core teachings presented in the Gospels: A universal and transformative message

Understanding the essence of the teachings attributed to the figure of Jesus, as recorded in the New Testament’s Gospels, requires a focus on the values and themes central to these narratives. While the historical authenticity of these accounts remains debated, the ethical and spiritual vision they convey is radical and transformative. At the heart of the Gospel message is a call to universal love, humility, non-violence, and personal spiritual transformation. This narrative emphasizes inner moral integrity and compassion over external rituals or societal hierarchies. Thus, without the necessity of a historical Jesus, the message from the Gospels also works as a powerful and relevant framework for ethical and spiritual life.

Speculating on Lazarus as the beloved disciple of Jesus

In contemporary scholarship on early Christianity, few scholars have stirred as much controversy as Richard Carrier. Known for his mythicist position — that Jesus may not have existed as a historical figure — Carrier often encourages us to read the Gospels not as reliable historical records, but as mythological and theological narratives created by early Christian communities. It is within this framework that we can examine one of his provocative suggestions: the possibility that the ‘beloved disciple’ in the Gospel of John, traditionally identified as John himself, was actually Lazarus — whom Carrier provocatively describes as Jesus’ closest companion, or, in modern parlance, his ‘boyfriend’.

Twelve Apostles, one myth: Debunking the foundation of institutional Christianity

The figure of Jesus in the Gospels is considered, according to Richard Carrier’s mythicist theory, to be an invented mythological character developed by early Christian communities. If Jesus himself is a mythic construct rather than a historical person, the narrative of the twelve apostles must similarly be viewed through a symbolic and theological lens rather than as a literal account of historical events. This perspective challenges the foundational claims of apostolic succession and institutional authority within the Church and underscores the core message of personal spiritual transformation, rather than a dependence on institutionalized mediation. In this post, we take a closer look at the mythicist critique of the twelve apostles and its implications for both the institutional Church and the personal Christian faith.

How Jesus became God: Exploring Bart D. Ehrman's thesis on the development of Christian belief in Jesus's divinity

Bart D. Ehrman’s How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee offers a meticulously researched account of how early Christians came to view Jesus as divine. Ehrman’s work traces the evolution of Jesus’s divinity from a historical Jewish preacher to a figure exalted by his followers after his death, culminating in the formalization of his divine status in the 4th century. While Ehrman argues for a historical Jesus who was gradually deified, Richard Carrier, a leading proponent of the mythicist position, rejects the idea of a historical Jesus altogether. Carrier posits that Jesus was originally conceived as a celestial figure whose story was later euhemerized — that is, placed into a historical narrative. In this post, we examine Ehrman’s thesis in light of Carrier’s theories, exploring how both perspectives illuminate the complex development of early Christian belief.

The resurrection of Jesus as a mythological tool for early Christian legitimization

The resurrection of Jesus stands at the heart of Christian theology and has long been a central symbol of faith, hope, and redemption. However, its mythological character and constructed nature deserve deeper scrutiny. Within early Christianity, the resurrection functioned both as a theological cornerstone and a strategic narrative tool for legitimizing Jesus as the Messiah, fulfilling Jewish prophecy and providing continuity after his death. Furthermore, the theological implications of the resurrection have profoundly shaped Christian philosophy and institutional power, positioning the Church as the steward of divine authority. In this post, we take a closer look at the resurrection of Jesus as a mythological construct and explore its theological significance and institutional implications.

The role of sacrificial blood rituals in Judaism and its reinterpretation in Christianity

Blood sacrifice holds a profound and complex role within the context of Jewish religious tradition, reflecting both its ancient cultural origins and its theological evolution. This symbolism extends into the early Christian reinterpretation of sacrificial practices, culminating in the belief in Jesus’ sacrificial death. In this post, we take a closer look at these practices within their historical and cosmological frameworks ti better understand why blood sacrifice was seen as essential and how it became a central theme in the development of Christianity – whether Jesus is viewed as a historical figure or a ‘celestial construct’.

Why did Jewish apocalypticism culminate in the 1st century CE?

Throughout history, human societies have often grappled with the notion of an impending apocalypse — a final, cataclysmic event that would reshape or end the world as they knew it. For the Jewish people, the idea of doomsday gained prominence during their tumultuous history under foreign rule, evolving into a complex eschatological framework that would later influence Christianity. Inspired by a talk I recently watched by Richard Carrier titled ‘From Noah’s Flood to Rapture Day’, this post explores the origins and development of Jewish apocalyptic beliefs, tracing their roots from Persian Zoroastrian influences to the widespread messianic fervor of the 1st century CE. We will explore how these beliefs culminated in a series of failed messianic movements and ultimately shaped the emergence of Christianity as a surviving apocalyptic sect.

Zalmoxis: The Thracian cult that may have influenced the conception of Jesus

Zalmoxis is a figure deeply rooted in the spiritual traditions of the ancient Thracians, specifically the Getae, a tribe inhabiting regions corresponding to modern-day Romania and Bulgaria. His narrative, as recorded by ancient Greek sources such as Herodotus, portrays him as a teacher, prophet, or even a god who profoundly influenced the religious and philosophical outlook of the Getae. Beyond his historical and mythological significance, Zalmoxis has become a focal point in modern discussions about the origins and development of mystery cults in antiquity. In this post, we explore Zalmoxis’s role in Thracian religion, his connections to Greek mystery traditions, and Richard Carrier’s interpretation of his cult’s significance as a precursor to Christianity.

Enoch: Another exemplar for the Jesus narrative?

The mythological framework surrounding early Christianity has been a topic of considerable debate a long time. Among scholars who advocate a non-historical or mythological Jesus, such as Richard Carrier, the evolution of Jesus as a theological construct becomes a lens through which the influence of apocryphal texts can be assessed. One of the key texts in this discourse is the Book of Enoch (also known as 1 Enoch), a Jewish pseudepigraphal work that profoundly shaped Second Temple Jewish thought.

Philo of Alexandria's logos concept and its potential influence on the development of the Jesus narrative

The question of how early Christians conceptualized Jesus and whether this figure was initially understood as a historical person or a celestial being has fueled significant scholarly debate. One prominent hypothesis, advanced by Richard Carrier, suggests that the original Christian understanding of Jesus was as a celestial being, akin to an angel or intermediary figure, who was later historicized into a real human person. Central to Carrier’s argument is the idea that this celestial Jesus may have been influenced by earlier Jewish theological constructs, particularly Philo of Alexandria’s writings about the logos. However, while Philo’s logos shares certain attributes with the early Christian depiction of Jesus, Philo never names this figure ‘Jesus’ or explicitly associates it with the messianic figure of Christian tradition. This post explores Philo’s concept of the logos, its relationship to angelic intermediaries, and Carrier’s argument that early Christians conceived of Jesus as a celestial being modeled after such theological constructs.

Richard Carrier and the historicity of Jesus: Was Christianity born from a mystery cult?

The question of whether Jesus of Nazareth was a historical individual or a purely mythical figure has long engaged theologians, historians, and laypeople alike. In his book, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (2014), Richard Carrier challenges conventional scholarly assumptions and proposes that Christianity could have originated without a historical founder. Instead, it might represent a Jewish adaptation of what Carrier calls a ‘mystery cult, following patterns already established in other ancient Mediterranean religious traditions. Drawing upon the scholarly consensus, methodological critiques, parallel religious traditions, textual analysis of the Pauline epistles, and the literary nature of the gospels, Carrier puts forth an argument suggesting that early Christians may have begun with the worship of a celestial Jesus and only later placed him into human history. This post summarizes and expands upon the main lines of argument Carrier presents, based on a recorded talk in which he outlines the major findings of his research.

The mythological character of the Gospels: A critical examination of Richard Carrier's theories

The figure of Jesus Christ has been central to Western civilization for nearly two millennia, yet the nature of the New Testament narratives remains a matter of intense debate. Richard Carrier, an American historian and philosopher, has argued that early Christian texts, particularly the gospels, are not historical biographies but mythological constructs designed to convey theological truths. This hypothesis places the gospel accounts within a broader tradition of ancient religious storytelling, where myth and symbolism often served as vehicles for spiritual meaning.

How Paul's epistles engineered early Christianity

The epistles of Paul, often regarded as the cornerstone of Christian theology, were among the earliest written documents of the New Testament. Far from casual correspondence, these letters were carefully constructed to address pressing issues within emerging Christian communities. Their content reveals not only Paul’s theological convictions but also his strategic efforts to unify diverse groups, define doctrinal foundations, and establish his authority as a leader within the early church. In this post, we explore the intentionality behind Paul’s epistles, analyze their historical context, theological objectives, and their profound impact on the development of Christianity.

Scriptures rewritten: How pseudepigraphy shaped the New Testament

The New Testament, a foundational collection of texts for Christianity, consists of 27 books that span a range of literary genres, including historical narratives, theological treatises, letters, and apocalyptic visions. Traditional Christian views hold that these books were written by apostles or their close associates, lending them an air of direct apostolic authority. However, modern biblical scholarship has questioned the authenticity of several New Testament books, suggesting that many were forged or editorially reworked in antiquity. In this post, we explore the phenomenon of pseudepigraphy (writing in the name of another) in the New Testament, the historical context of forgery, and the implications for understanding early Christian communities.

Christianity: A syncretic religion in historical context

Christianity, as one of the world’s major religions, has long been the subject of extensive academic inquiry. Its origins, core teachings, and historical development have been studied through various disciplinary lenses, including theology, history, anthropology, and comparative religion. Scholars have debated how Christianity emerged, the nature of its earliest communities, and how it evolved into an institutionalized faith. In this post, we examine current scholarship on Christianity, focusing on its syncretic nature and historical context.

The phenomenon of traveling preachers in 1st-century Judea and Galilee

The role of itinerant preachers in 1st-century Judea and Galilee is an essential aspect of understanding the religious and social dynamics of the period. This broader context sheds light on figures like Jesus, who emerged within a tradition of wandering teachers and prophets. Examining the cultural and historical backdrop of itinerant preaching reveals a landscape marked by socio-political unrest, religious ferment, and apocalyptic expectations, where individuals carrying messages of divine justice, repentance, and hope played significant roles.

The rise of Rabbinic Judaism: Jewish philosophy after the Temple's destruction

The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE by the Romans marked a profound turning point in the history of Judaism. The event not only brought an end to the central institution of Jewish religious life but also precipitated a period of theological, philosophical, and cultural transformation. In the aftermath, Rabbinic Judaism emerged as the dominant expression of Jewish religious thought and practice, redefining the foundations of Jewish identity and worship.

Jesus in the setting of Jewish philosophy of his time

The figure of Jesus of Nazareth, as portrayed in the Gospels and whose teachings became the foundation of Christianity, cannot be understood apart from the Jewish philosophical and theological context in which he is set. Far from being depicted as an outsider to Judaism, the Jesus figure presented in these texts is deeply embedded in the Jewish intellectual and religious traditions of first-century Palestine. His teachings, actions, and self-representation as described in the Gospels reflect the philosophical debates, sectarian dynamics, and theological currents that characterized Second Temple Judaism. Understanding the historical context of the first century CE in Judea is crucial for situating Jesus within Jewish thought. The period was marked by profound social, political, and religious transformations, including Roman imperial rule, internal Jewish divisions, and widespread eschatological expectations. These dynamics created an environment ripe for religious innovation and reform, setting the stage for the emergence of new theological interpretations.

The evolution of Judaic philosophy and thought: A matter of constant development

Throughout its long history, Judaism has demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for adaptation and renewal, shaped by both internal evolution and external pressures. Far from being an isolated or static tradition, Judaism has continuously interacted with surrounding cultures, absorbing, reinterpreting, and, at times, resisting external influences. These interactions have played a significant role in the development of Jewish theology, religious practice, and communal identity. This article explores the dynamic relationship between Judaism and the cultures it encountered, highlighting how these exchanges have contributed to the rich diversity of Jewish thought and life.

The role of synagogues in the diaspora

The expansion of the Jewish diaspora during the Hellenistic and Roman periods profoundly shaped the nature and influence of Judaism within the Mediterranean world. As Jewish communities established themselves in the Greek-speaking metropolises of the Roman Empire, synagogues emerged as central institutions for religious, social, and cultural life. These spaces facilitated the practice of Judaism in a diasporic context, enabled the transmission of Jewish teachings in the lingua franca of Greek, and became venues of interaction between Jews and non-Jews. The unique role of synagogues as both sacred and communal spaces contributed to the gradual popularization of Judaism in the Roman world, while also highlighting tensions between inclusivity and exclusivity in Jewish religious practice.

The Jewish diaspora and religious interactions in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire of the first centuries BCE and CE was a dynamic arena of cultural and religious interaction, where diverse traditions encountered and influenced one another. Within this complex environment, Judaism occupied a unique position, both as an ancient monotheistic tradition and as a religion with a significant diasporic presence. The interactions between Judaism and other religions during this period not only shaped Jewish identity but also set the stage for the emergence of Christianity.

Hellenistic influence on Jewish theology: The case of the Septuagint and Philo of Alexandria

The encounter between Jewish theology and Hellenistic culture in the centuries following Alexander the Great’s conquests marked a transformative period in the history of Judaism. This era, known as the Hellenistic period, was characterized by the fusion of Greek philosophical ideas and Jewish religious traditions, leading to significant developments in Jewish thought. Two key manifestations of this synthesis are the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, and the works of Philo of Alexandria, a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher. Both the Septuagint and Philo’s writings illustrate how Jewish theology adapted and responded to the intellectual and cultural milieu of the Greco-Roman world.

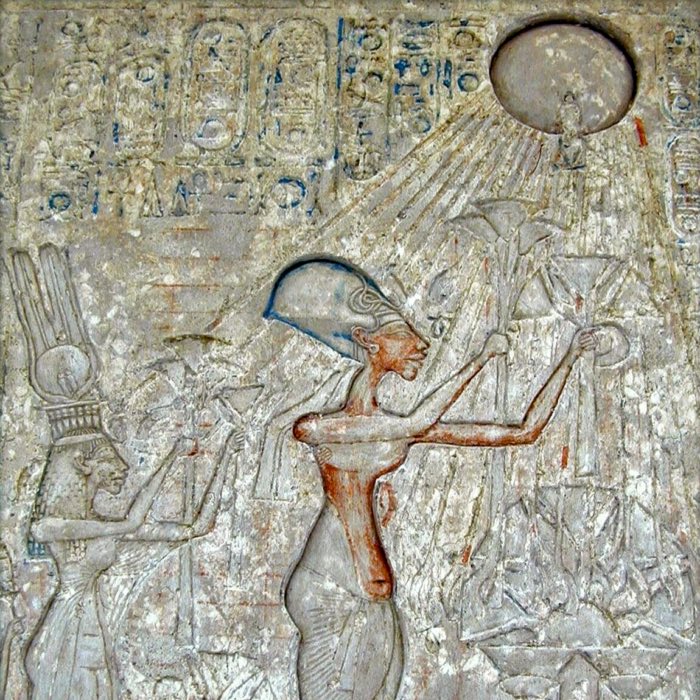

The influence of Egyptian religious concepts on Judaism

The religious traditions of ancient Egypt, with their deep theological frameworks, complex pantheon, and ritual practices, played a significant role in shaping the ancient Near Eastern religious landscape. Given the long historical interaction between Egypt and the Israelite people, including the Israelites’ sojourn in Egypt and subsequent Exodus, it is natural to explore how Egyptian religious ideas may have influenced the development of Judaism. While Judaism ultimately developed into a strictly monotheistic religion, certain themes, symbols, and theological ideas found in Egyptian religion appear to have left a lasting mark on Jewish thought and practice.

Zoroastrian influence on Judaism

The interaction between Zoroastrianism and Judaism is a subject of considerable scholarly interest, particularly because both religious traditions share striking similarities in their cosmology, eschatology, and ethical dualism. Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest known monotheistic religions, developed in ancient Persia around the 6th century BCE, a period that coincides with significant historical events in Jewish history, such as the Babylonian exile and subsequent Persian rule. This temporal and geographical proximity provides a plausible framework for cultural and religious exchange.

Do Jewish and Christian philosophy differ in openness to development?

TAfter exploring key aspects of Jewish philosophy in my recent posts, I began to wonder whether it might be more open and flexible to development than Christian philosophy. Both traditions have long histories of engaging with questions about ethics, existence, and human purpose. Yet, it appears that there is a critical distinction in how each tradition approaches intellectual development, reinterpretation, and the role of debate in theological inquiry. In this post, I therefore aim to examine this subject by exploring whether Jewish and Christian philosophies differ in their openness to development, focusing on key characteristics of both traditions, their historical contexts, and their respective attitudes toward philosophical evolution.

The philosophy of wisdom in the last century BCE and its influence on the Christianity

The final century before the Common Era was a period of profound intellectual and cultural exchange in the Mediterranean world, marked by the confluence of Jewish, Greek, and Roman philosophical traditions. Central to this era was the philosophy of wisdom, which emerged as a distinct mode of thought blending ethical reflection, theological speculation, and practical guidance for human flourishing. This philosophy, particularly as expressed in Jewish wisdom literature and its interaction with Hellenistic traditions, significantly influenced the development of early Christian thought.

Jewish ethical philosophy: From the prophets to Rabbinic thought

Jewish ethical philosophy, as articulated from the time of the biblical prophets to the development of rabbinic thought, reflects a profound and evolving tradition that grapples with questions of morality, justice, and the divine-human relationship. Rooted in the covenantal framework established in the Torah, Jewish ethical philosophy emphasizes the integration of divine law with human behavior, fostering a vision of ethics that is both transcendent and practical. Over centuries, this vision was enriched and reinterpreted through the prophetic call for justice, the wisdom literature’s emphasis on individual virtue, and the rabbinic engagement with textual interpretation and legal reasoning.

Yahweh's wager with the devil: The narrative of Job and the sadism of a deity

Few biblical narratives provoke as much discomfort and philosophical reflection as the Book of Job. This ancient story begins with a striking premise: Yahweh, the supreme deity, enters into a wager with Satan concerning the faithfulness of his servant Job. Job, described as ‘blameless and upright’, is subjected to extreme suffering, ostensibly to test whether his piety is rooted in genuine devotion or mere transactional loyalty. This unsettling portrayal of divine behavior raises troubling questions about the morality and nature of Yahweh’s actions—questions that have inspired interpretations ranging from theological apologetics to existential critiques.

The power of narrative: Theology through stories in Jewish scripture

The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, stands as one of the most influential collections of religious texts in human history, not merely for its theological content but for the narrative form through which its ideas are conveyed. Unlike systematic theological treatises, the Jewish scriptures primarily communicate theological concepts through stories — narratives that span from creation myths and patriarchal sagas to accounts of national crises, exiles, and restorations. These stories serve not only as records of collective memory but also as vehicles for theological reflection, moral instruction, and cultural identity.

The concept of sin in Judaism and its central emphasis

The concept of sin (chet) in Judaism is deeply embedded within its theological framework, serving as a pivotal element in the relationship between humanity and YHWH. Rooted in the covenantal relationship established in the Torah, sin is understood as a deviation from the divine will, a breach of the moral and legal obligations set forth in Jewish law (halakhah). Unlike some religious traditions that view sin primarily as an inherent flaw or state of being, Judaism conceptualizes sin in dynamic and relational terms, emphasizing human agency, repentance, and the possibility of reconciliation.

The development of the concept of the Messiah in Judaism

The concept of the Messiah (Mashiach, ‘anointed one’) is one of the most enduring and evolving theological ideas in Judaism, reflecting the dynamic interplay between historical events, theological reflection, and communal aspirations. Rooted in the Hebrew Bible, the messianic idea emerged as a response to the political, social, and spiritual crises faced by the Jewish people, evolving over centuries into a rich and multifaceted tradition. While initially centered on kingship and divine appointment, the concept later expanded to encompass apocalyptic, eschatological, and redemptive dimensions.

The consequence of the Babylonian exile: The placeless god and a religious revolution

The Babylonian exile (586–539 BCE) stands as one of the most transformative events in the history of ancient Israel and the development of its religion. This period, marked by the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem and the forced displacement of the Judean elite to Babylon, presented an existential crisis for the exiled community. The loss of the Temple, the central locus of worship and divine presence, necessitated a rethinking of theological concepts and religious practices. The result was a revolutionary shift in the conception of God and the nature of worship, with YHWH emerging as a ‘placeless’ deity — one no longer bound to a physical sanctuary or specific geographical location. This theological innovation had profound implications for the development of Judaism and later monotheistic traditions, as it marked a departure from the territorial and cultic structures typical of ancient Near Eastern religions.

On the historicity of central figures of the Tanakh

The Tanakh, or Hebrew Bible which contains the Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim, contains narratives that have shaped religious, cultural, and historical perspectives for millennia. Central to these narratives are key figures who play significant roles in the origin and development of ancient Israel. While traditional views regard these figures as historical individuals, modern biblical scholarship and archaeology have cast doubt on their historicity. In post, we examine the available evidence and scholarly debates surrounding the historicity of some of the most prominent figures in the Tanakh, including Moses, Abraham, Joshua, David, Solomon, and Job, emphasizing current scientific perspectives.

Origins of the books of the Jewish scriptures

The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, often perceived as a divinely inspired and immutable text, is in fact the product of centuries of human effort, cultural evolution, and theological reflection. Far from being a monolithic or static creation, the Bible emerged through a dynamic process of oral tradition, textual composition, compilation, and redaction. This process was deeply intertwined with the historical and social developments of ancient Israel and its surrounding cultures. The Bible’s origins reveal it to be a living and evolving work, reflecting the diverse voices, perspectives, and experiences of its authors and editors.

Archaeological evidence of the Israelites

The search for archaeological evidence of the Israelites — an ancient people whose narratives form the backbone of the Hebrew Bible — has long fascinated scholars and researchers. Archaeology provides a lens through which to understand the historical context of the Israelites, offering insights into their origins, settlement patterns, culture, and interactions with neighboring civilizations. However, the interpretation of archaeological data in relation to the biblical narrative remains a complex and often contentious field, shaped by differing methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and historical assumptions. In this post, we examine the archaeological evidence associated with the Israelites, focusing on their emergence in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (circa 1200–1000 BCE) in the Levant, their settlement in the central highlands, and their cultural and material practices. We also discuss the challenges and debates that arise in correlating archaeological findings with the biblical record.

Origins of YHWH and the early monolatry in the Hebrew Bible

The origins of YHWH, the God of Israel, and the early stages of monolatry as expressed in the Tanakh (or Old Testament) form a critical area of study in understanding the development of Jewish theology. The name YHWH first emerges in biblical tradition as the unique deity of the Israelites, but its historical and cultural antecedents suggest a more complex process of religious evolution. Early Israelite religion was not immediately monotheistic but likely began as a form of monolatry — a system in which one deity is exclusively worshiped without denying the existence of others. Over time, this monolatrous devotion to YHWH evolved into the monotheism that characterizes later Jewish thought.

A brief introduction to Judaism and its profound historical and philosophical significance

Judaism is not only one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions, but it also serves as a foundation upon which some of the most influential traditions in the Western world have developed, particularly Christianity. Understanding Judaism requires a multifaceted exploration of its origins, its interaction with surrounding cultures, and the rich philosophical frameworks that have emerged within its tradition. I therefore thought, it would be beneficial to provide a brief series of posts on Judaism, exploring its historical and philosophical significance. While it is of course impossible to cover all aspects of such a vast and complex tradition in a few posts, I hope to provide a starting point for those interested in further exploring Judaism and its profound influence on the world’s religious and philosophical landscape

The influence of Greek philosophy on Christian thought: Foundations of Christian philosophy

The encounter between Greek philosophy and the nascent Christian tradition represents one of the most profound and transformative moments in the history of intellectual thought. Christianity, emerging from its Judaic roots and expanding into the Greco-Roman world, engaged deeply with the philosophical traditions of antiquity. Greek philosophy provided early Christian thinkers with the intellectual tools to articulate their theology, address complex metaphysical questions, and engage with the broader cultural and philosophical currents of the Roman Empire.

The interaction of Greek philosophy and Jewish thought: Hellenistic influence and the dynamics of Jewish philosophy before the Common Era