Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 11/52

Zen: Presence as practice

Zen does not begin with doctrines, rituals, or lofty goals. It begins right here, in this breath, this step, this cup of tea. At the heart of Zen is an unwavering emphasis on the now — the direct, unmediated encounter with life as it unfolds. It is not about preparing for a better future, accumulating merit, or escaping the world. It is about fully inhabiting this moment, because this moment is all there is. This teaching, while seemingly simple, carries profound implications. It is not a call to hedonism or passivity, but to wakefulness — to see clearly, feel deeply, and act precisely. Zen says: do not postpone your life. Enlightenment is not a distant peak to be reached someday; it is the immediacy of being present, without grasping, without fleeing.

Kenshō and Satori: Awakening in Zen

In Zen Buddhism, the terms kenshō (Japanese: 見性, ‘seeing one’s nature’) and satori (悟り, ‘understanding’ or ‘awakening’) are central concepts that describe the experience of sudden insight into the true nature of reality. Unlike the gradual, step-by-step cultivation of wisdom often emphasized in other Buddhist traditions, Zen speaks of a direct, immediate realization that cuts through conceptual thinking and reveals things as they truly are. In this post, we explore what kenshō and satori mean in the Zen context, how they are understood and approached, and how they relate to other core teachings such as tathatā (suchness), śūnyatā (emptiness), and dependent origination. We will also examine misunderstandings around these terms, their role in the Zen path, and how awakening is both a beginning and a continuation of practice.

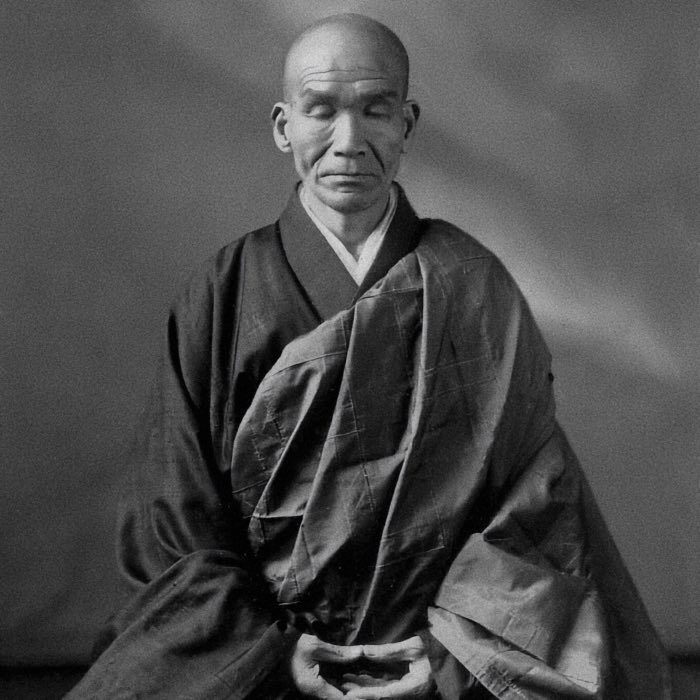

The central element of Zen: Zazen

Zazen, literally ‘seated meditation’, is not merely one technique among others in Zen; it is the very heart of its path. More than a means to an end, it embodies the entirety of the Zen approach: direct, immediate, and grounded in the here and now. Zen does not prioritize reading scriptures, performing rituals, or climbing hierarchical stages of attainment. Instead, it points us to reality as it is, and asks us to sit down and meet it. Why sitting? Because zazen strips away distractions. In stillness and silence, the usual dramas of goal-setting, striving, and self-definition begin to fall away. We return to the body, the breath, the ground beneath us. In this simplicity, we come face to face with suchness (tathatā), the unfiltered presence of things, free from projection and resistance. Zazen is not about producing insight; it is insight embodied. Not about chasing enlightenment, but realizing it was never absent. Thus, sitting becomes the most radical act: to do nothing, to go nowhere, to be fully present. And in this presence, Zen teaches, everything is revealed.

Suchness as reality: Zen, tathatā, and the interplay of emptiness

In the Mahāyāna and Zen traditions of Buddhism, the term tathatā (Sanskrit; zhēnrú 真如 in Chinese; shinnyo 真如 in Japanese) stands for one of the most pivotal yet elusive ideas: suchness, or the reality of things just as they are. As explored in our earlier post on Tathatā: Buddhism’s view on reality as it is, this concept captures the direct, unfiltered encounter with phenomena — prior to conceptualization, judgment, or dualistic thinking. It names not a transcendent essence but the experiential texture of reality when seen without clinging, projection, or resistance. In Zen, this notion finds radical expression through non-dual immediacy, poetic evocation, and embodied practice. But suchness is never isolated. Within Buddhist thought, it arises through a web of interrelated concepts: śūnyatā (emptiness), pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination), the two truths, and in the East Asian context, interpenetration. This post builds on our earlier reflections and extends them into a broader network of insight. We explore how suchness can be understood as the experiential side of emptiness, the realized face of dependent origination, and the dynamic field in which all things reflect and contain each other. Zen, in this view, becomes not a mystical path but a direct, intimate embrace of the real — not as an idea, but as encounter.

Zen’s way of knowing: From conceptual thought to direct realization

Zen (Chán) Buddhism places a radical emphasis on direct, non-conceptual realization of reality. Unlike the analytic, scholastic traditions found in some schools of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, Zen centers on awakening that occurs beyond words and letters (教外别传, jiàowài biéchuán), through intuitive insight into one’s true nature. This epistemological orientation links Zen to Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy and its deconstructive critique of conceptual elaboration (prapañca). But Zen moves beyond critique into praxis: it seeks not to defeat concepts for their own sake, but to open the practitioner to a different kind of knowing altogether. In this post, we explore the epistemology of Zen as a unique mode of Buddhist insight. It traces the shift from conceptual cognition (vijñāna) to direct knowing (prajñā), highlights key contrasts with discursive methods, and considers how Zen’s ‘non-knowing’ (不知, bù zhī) functions not as ignorance but as awakened awareness.

The influence of Daoism and Confucianism on Chinese Chán Buddhism

The emergence of Chán Buddhism in China was not an isolated event but the result of centuries of cultural, philosophical, and religious interaction. While rooted in Indian Buddhist traditions, particularly the Mahāyāna emphasis on emptiness (sūnyatā) and direct realization, Chán developed in a Chinese intellectual and spiritual environment shaped by Daoism and Confucianism. Among these, Daoism played a particularly significant role in shaping the tone, language, and orientation of early Chán, while Confucianism contributed more subtly, often influencing social structures and ethical concerns. In this post, we examine how these indigenous traditions influenced the development of Chán, both in its formative centuries and in its later interpretations.

The Five Houses of Chán: The diversification of Chinese Zen

Following the ascendancy of the Southern School and the widespread acceptance of Huineng’s approach to sudden enlightenment, Chinese Chán Buddhism entered a new phase of institutional and pedagogical development. This era, spanning the late Tang (9th century) and early Song (10th century), witnessed the emergence of what later came to be known as the Five Houses or Five Schools of Chán (五家, Wǔjiā). Rather than representing rigid institutions, these Houses were loose networks of master-disciple lineages that emphasized particular styles of teaching, training methods, and approaches to awakening. All five Houses grew from within the doctrinal and practical soil of the Southern School. While they shared Huineng’s emphasis on sudden enlightenment and direct experience, each cultivated its own tone and orientation, often shaped by local conditions, charismatic leaders, and pedagogical innovation. Some would fade over time, while others would leave a lasting mark on the global transmission of Zen, particularly in Japan. In this post, we provide a brief overview of each of the Five Houses — Guiyang, Linji, Caodong, Yunmen, and Fayan — with attention to their core characteristics, historical significance, and corresponding developments in Japanese Zen.

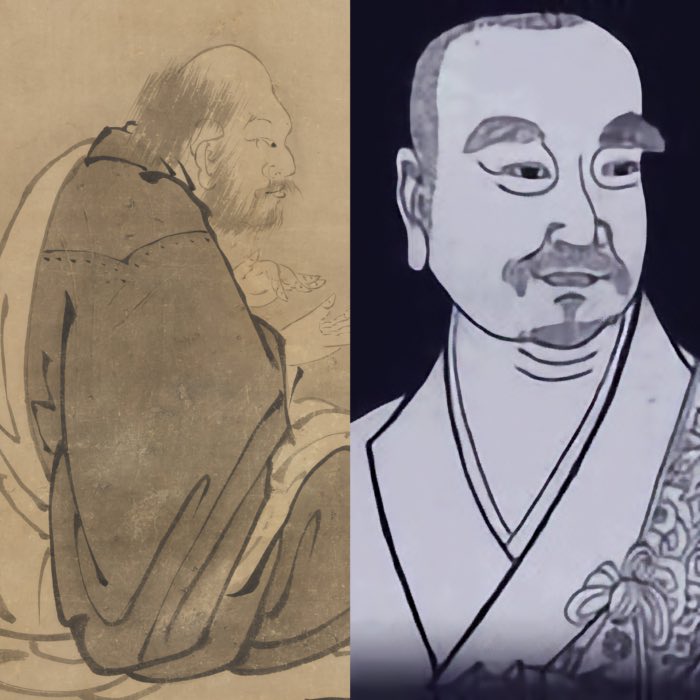

The Northern and Southern Schools of early Chinese Chán Buddhism

The division between the so-called Northern and Southern Schools of Chán Buddhism represents one of the most formative moments in the development of Chinese Zen. Though often presented as a sharp doctrinal conflict between gradual and sudden enlightenment, this dichotomy has been the subject of both historical exaggeration and modern scholarly reevaluation. Still, the polemics and personalities involved in this split, particularly those surrounding Shenxiu and Huineng, had profound consequences for the trajectory of Zen thought and institutions in East Asia. This post explores the historical roots of this division, the philosophical and pedagogical positions attributed to each school, and the broader significance of the dispute. While the Southern School would eventually come to define the orthodox self-understanding of Chán, the Northern School’s influence in courtly and monastic circles at the time was substantial and deserves closer attention..

Dajian Huineng: The sixth patriarch and the great divergence in Chinese Zen

Dajian Huineng (大鑒惠能; Japanese: Daikan Enō) is widely regarded as the Sixth Patriarch of Chinese Zen (Chán) and one of its most transformative figures. While his historical biography is shrouded in uncertainty and myth, the ideas and texts associated with his name — especially the Platform Sūtra — profoundly shaped the trajectory of Zen thought and practice. Huineng’s legacy marks a watershed in the development of Zen, characterized by a decisive shift away from gradualist approaches to enlightenment and toward the idea of sudden awakening, accessible to all regardless of education or background. Huineng’s rise to prominence also marks a critical moment in the institutional history of Chán, as the lineage split between Northern and Southern interpretations. His story, whether taken as legend, history, or both, stands as a powerful narrative of anti-elitism, immediacy, and direct realization. In this post, we explore Huineng’s historical and legendary life, his teachings, the influence of the Platform Sūtra, and the broader impact of his legacy on the direction of East Asian Zen.

Daman Hongren: The fifth patriarch and the maturation of East Mountain Zen

Daman Hongren (弘忍; Japanese: Daiman Kōnin) stands as one of the most influential figures in the formative history of Chinese Chán (Zen) Buddhism. As the fifth patriarch, he inherited a tradition that had begun to settle into communal structures under his teacher, Daoxin, and took decisive steps to deepen its philosophical articulation, broaden its pedagogical reach, and solidify its institutional presence. Hongren is most widely recognized as the teacher of Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch, but his own role is foundational in establishing what would later be called the ‘East Mountain Teachings’. These teachings emphasized seated meditation, direct awareness, and the inner realization of Buddha-nature, while avoiding elaborate metaphysics or scholastic commentary. Under Hongren’s guidance, Zen became not only a lineage of awakening but a concrete community, rooted in disciplined practice and shared insight.