Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 12/52

Daoxin: The fourth patriarch and the institutional grounding of Zen

Dayi Daoxin (道信; Japanese: Dai’i Dōshin) occupies a crucial position in the formation of Chinese Chán (Zen) Buddhism. Recognized as the fourth patriarch in the traditional Zen lineage, he marks a transition from the loosely affiliated, wandering teacher-student model of the early patriarchs to a more stable, monastic framework. While retaining the emphasis on direct realization and meditative discipline, Daoxin helped establish Chán as a viable and coherent school within Chinese Buddhism. His long tenure at Mount Shuangfeng, his accessible teachings, and his success in attracting a large monastic following contributed significantly to Chán’s consolidation. Through Daoxin, Zen began to develop not only as a lineage of spiritual insight but also as a living institution, rooted in community and practice.

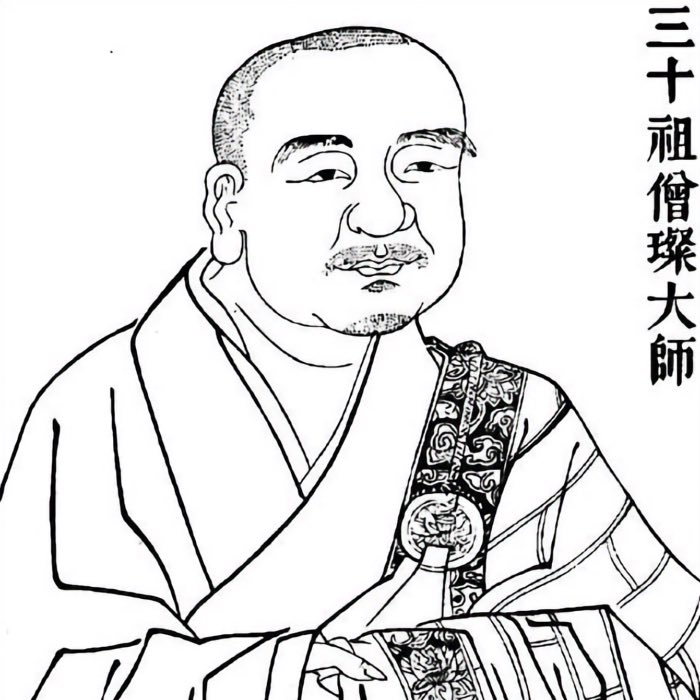

Sengcan: The third patriarch of Chán Buddhism and the spirit of equanimity

Jianzhi Sengcan (僧璨; Japanese: Kanchi Sōsan) is traditionally regarded as the third patriarch of Zen (Chán) Buddhism in China, the disciple and Dharma heir of Dazu Huike. Though little is known about his life, and few direct teachings can be reliably traced to him, Sengcan’s reputation in Zen tradition is anchored in both his role as transmitter of the lineage and his association with the celebrated Zen poem Xinxin Ming (Faith in Mind). His image, as transmitted through generations of Zen lore, reflects qualities of balance, equanimity, and profound inner stillness. In this post, we try to put together as much as possible about Sengcan’s life, including his teachings, the Xinxin Ming, and his legacy in the Zen tradition.

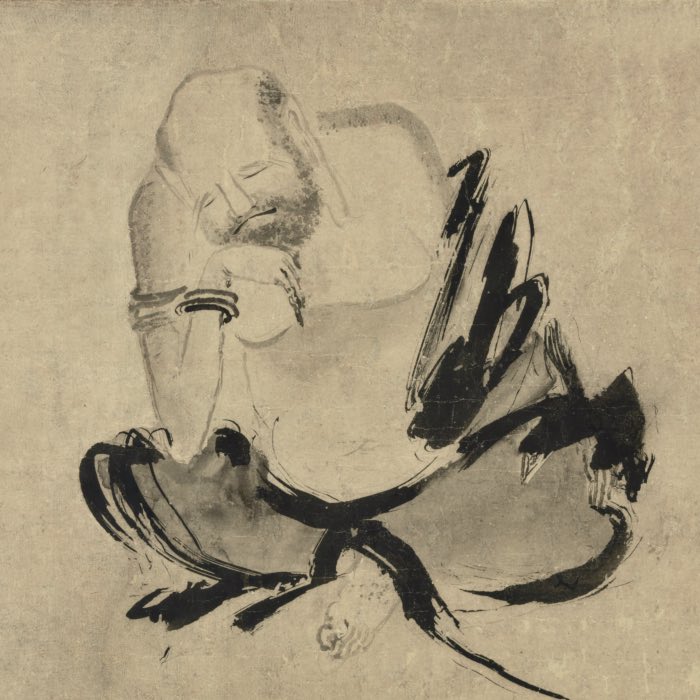

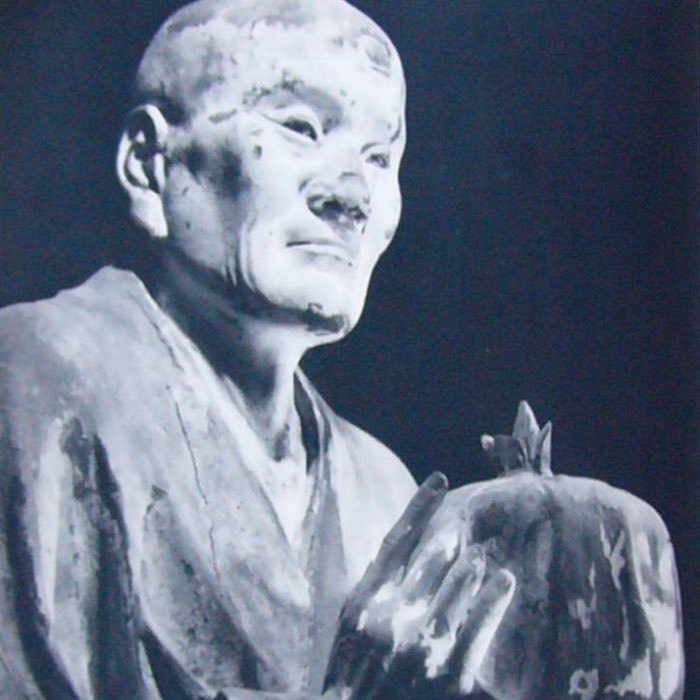

Dazu Huike: The second patriarch of Chán Buddhism and the embodiment of sincere seeking

Dazu Huike (大祖慧可; Japanese: Taiso Eka) is known in Zen (Chán) tradition as the second patriarch of Chinese Buddhism and the foremost disciple of Bodhidharma. While details of his life remain shrouded in a mix of history and hagiography, Huike’s symbolic and pedagogical legacy remains powerful. He is remembered not only as the recipient of Bodhidharma’s mind-to-mind transmission, but also as the embodiment of radical sincerity and dedication to awakening. The dramatic stories associated with Huike — including the infamous account of him severing his own arm to demonstrate resolve — are not merely tales of asceticism or extremity. They function within the Zen tradition as mythic expressions of the urgency, courage, and directness expected on the path to liberation. This post explores the multi-faceted role of Huike within the early formation of Chán, examining both his legacy and the symbolic depth of the narratives that surround him.

The Six Patriarchs of Zen: Foundations and transformations of the Chán tradition

Zen (Chán) places special emphasis on direct realization, meditative practice, and the transmission of insight from teacher to student. Central to this lineage-based model of spiritual authority is the narrative of the ‘Six Patriarchs’ — a succession of figures who, according to tradition, preserved and conveyed the essence of Zen through a direct, mind-to-mind transmission. Far more than mere historical personalities, these patriarchs came to symbolize key developments in the evolution of Zen thought and practice from its roots in India to its distinct formation in China. In this post, we briefly explore the lives and teachings of these six pivotal figures, tracing their impact on the development of Zen and its subsequent diversification into various schools.

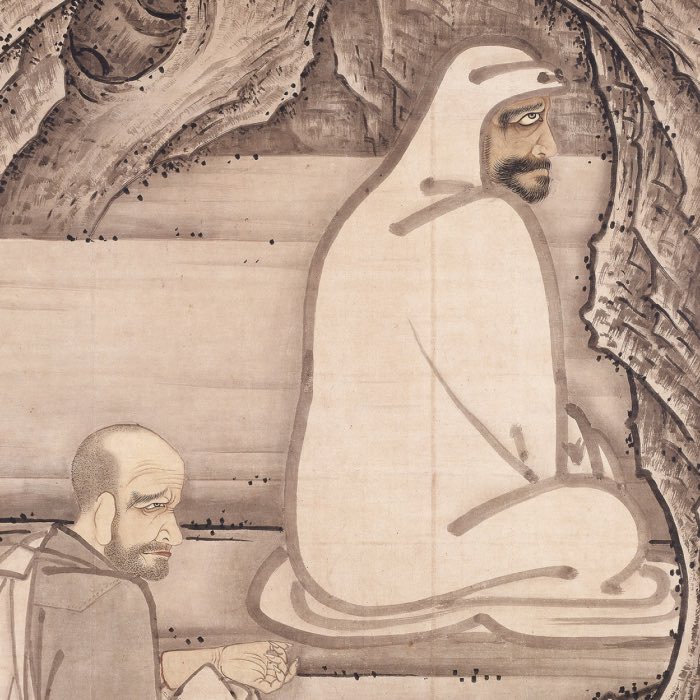

Bodhidharma’s coming from the West: Reassessing the myth and its historical substance

Bodhidharma occupies a singular position in the history of Zen Buddhism: a semi-legendary figure who, though sparsely attested in early sources, is later credited with founding the Chán (Zen) tradition in China. His image — a fierce, bearded monk arriving from the West, meditating for years in silence, and sparring intellectually with an emperor — has become iconic, yet his historical reality remains elusive. This post does not aim to either venerate Bodhidharma as a saintly founder or debunk him as a fabricated myth. Instead, it seeks to assess what can be understood of Bodhidharma as a symbol of a specific turning point in the development of East Asian Buddhism.

Zen Buddhism: Overview of its historical and philosophical roots

Zen Buddhism is frequently portrayed in modern popular culture as a set of cryptic sayings, minimalist aesthetics, and serene meditation gardens. However, these representations often isolate Zen from its deeper philosophical and historical foundations. Contrary to such portrayals, Zen is not an isolated or esoteric tradition detached from Buddhist roots. Rather, it is a school within Mahāyāna Buddhism, one that emphasizes direct experiential realization of the foundational teachings first articulated by Siddhartha Gautama and later refined in Mahāyāna thought, particularly through the Madhyamaka and Huayan traditions. This post marks the beginning of a new series exploring Zen Buddhism as a tradition deeply rooted in classical and Mahāyāna Buddhist thought. The first post in this series offers a contextual and philosophical overview of Zen Buddhism as a historically continuous development within the broader framework of Buddhist philosophy. It focuses on Zen’s unique interpretative lens, its roots in early Indian thought, and its evolution through Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese cultures.

Yogācāra and the nature of mind — Consciousness-only and the path to non-duality

After Nāgārjuna’s radical deconstruction of all views through śūnyatā and the two truths, Buddhist philosophy faced a new challenge: how to speak meaningfully about experience and practice without slipping back into metaphysical reification. The Yogācāra school, also known as Cittamātra (‘Mind-only’), emerged in response. Rather than opposing Nāgārjuna, Yogācāra complements his insights by turning from the negation of essence to an exploration of consciousness as the medium through which all experience arises. Yogācāra does not argue that everything is mental in the idealist sense; rather, it shows how our experience of reality is inextricably shaped by mental processes — and how liberation depends on transforming consciousness itself. In this post, we explore the core teachings of Yogācāra, its relation to Madhyamaka, and how it offers a vital bridge between analytical emptiness and the non-dual immediacy of Zen.

Asaṅga and Vasubandhu: Synthesizing Yogācāra thought

Asaṅga and Vasubandhu are two of the most influential thinkers in the history of Mahāyāna Buddhism, renowned for their foundational role in developing the Yogācāra, or ‘Consciousness-Only’, school. Working in the 4th and 5th centuries CE, these brothers synthesized philosophical analysis, meditative insight, and ethical reflection to create a comprehensive vision of how consciousness shapes experience and how liberation is possible. In this post, we explore their lives, core doctrines, and the lasting impact of their thought on Buddhist philosophy in India, East Asia, and beyond.

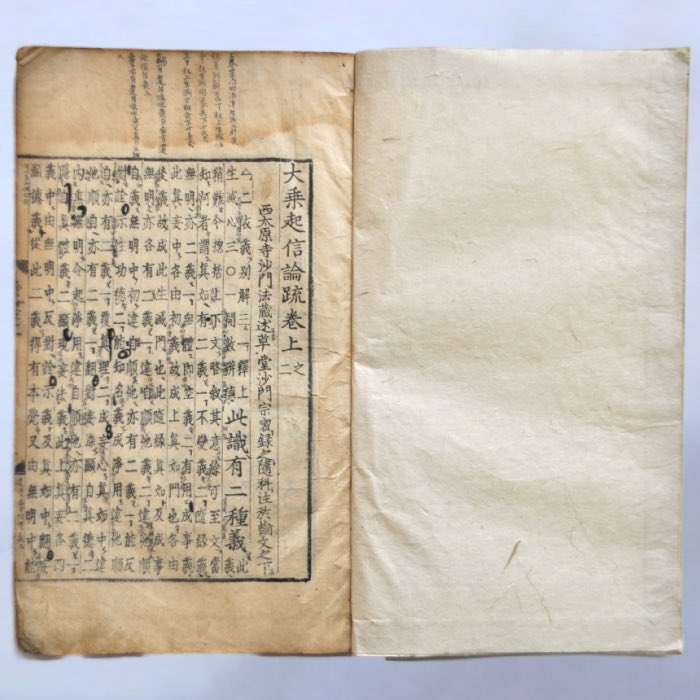

The Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna: Unifying mind and suchness

The Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna is a foundational text in East Asian Buddhism, renowned for its profound synthesis of Indian Mahāyāna doctrines and Chinese philosophical concerns. Traditionally attributed to Aśvaghoṣa but now widely regarded as a 6th-century Chinese composition, the text played a crucial role in shaping the doctrinal landscape of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese Buddhism. By articulating the concept of the ‘One Mind’ with its dual aspects of suchness and arising-and-ceasing, it offers a powerful framework for reconciling emptiness, Buddha-nature, and the process of awakening. In this article, we explore the origins, core teachings, and far-reaching influence of The Awakening of Faith, highlighting its significance as a bridge between philosophy and practice in the Mahāyāna tradition.

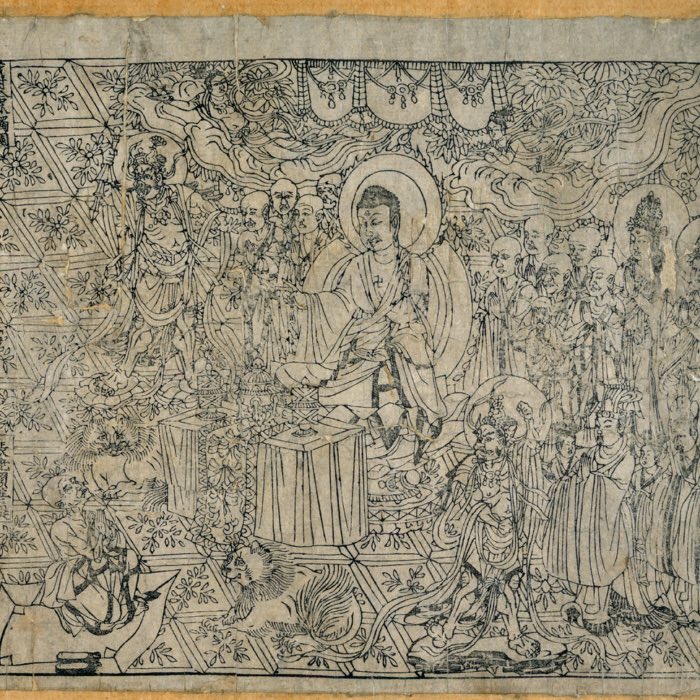

Prajñāpāramitā literature and the language of emptiness

The Prajñāpāramitā literature stands at the heart of Mahāyāna Buddhism, introducing the radical and transformative concept of emptiness (śūnyatā) and redefining wisdom (prajñā) as direct, non-conceptual insight into the nature of reality. Composed between the 1st century BCE and the early centuries CE, these texts challenged established Buddhist doctrines and inspired new currents of philosophical and meditative practice. In this post, we explore the origins, core themes, and far-reaching influence of the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, highlighting their role in shaping the language, thought, and spiritual aspirations of Mahāyāna traditions across Asia.