Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 32/52

Greek philosophy and the foundations of Western thought

Greek philosophy represents a pivotal chapter in the history of Western intellectual development. Originating in the ancient Mediterranean world, it marks a transformative shift from mythological explanations of the cosmos to systematic and rational inquiry — a movement encapsulated by the transition from mythos to logos. This post begins a series exploring the evolution of Greek philosophical thought, its key figures, and its impact on Western intellectual traditionsXT.

Aphrodite and the interconnections in the ancient world

While Nike and other angel-like figures in Greek mythology seem to have no connections to any Meospotamian deities, there is one goddess whose origins are deeply rooted in the Near East: Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty. Her worship and iconography bear striking resemblances to earlier deities of the region, particularly Inanna-Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. This connection reflects the significant cultural and religious exchanges that shaped early Greek religion, especially during the period of Orientalization in the eighth century BCE.

Multicultural interconnections and independent developments in early civilizations

The ancient world, though characterized by significant geographic, temporal, and cultural diversity, was interconnected through trade, migration, conquest, and shared intellectual traditions. Mesopotamia, often referred to as the cradle of civilization, stood at the nexus of these interconnections, influencing and being influenced by neighboring cultures such as the Egyptians, Hittites, Greeks, Persians, and the peoples of the Indus Valley. Despite the vast distances and centuries separating these civilizations, their exchanges facilitated the diffusion of ideas, technologies, and religious practices.

The emergence of early civilizations – A summary

The earliest civilizations in human history represent diverse cultural, geographical, and technological achievements that laid the foundation for modern societies. From the Fertile Crescent to the Andean highlands, these civilizations display remarkable similarities in their pathways to complexity while showcasing unique adaptations to their environments. By examining the civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, India, the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations, the Hittite Empire, the Nok Culture, the Kingdom of Kush, the Canaanite Civilization, the Korean Gojoseon Kingdom, the Jomon Culture of Japan, the Elamite Civilization, the Olmec and Maya civilizations, the Norte Chico civilization, and the Inca Empire, we can discern overarching patterns and distinctive features that defined early human development.

The Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, known as Tawantinsuyu in Quechua, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America, flourishing between the 15th and early 16th centuries CE. Centered in the Andean highlands of South America, the empire extended across present-day Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina. Renowned for its advanced infrastructure, administrative organization, and cultural achievements, the Inca Empire represents the pinnacle of Andean civilization. Its legacy continues to influence modern Andean cultures.

The Norte Chico civilization

The Norte Chico civilization, also known as the Caral-Supe civilization, is one of the oldest known complex societies in the Americas. Flourishing between approximately 3000 BCE and 1800 BCE along the arid coast of modern-day Peru, Norte Chico represents an early cradle of civilization in the New World. Distinguished by monumental architecture, complex societal organization, and a reliance on maritime and agricultural resources, it predates more widely known Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations like the Maya and Inca.

The Maya civilization

The Maya civilization, which flourished between approximately 2000 BCE and 1500 CE, represents one of the most sophisticated and enduring cultures of the ancient Americas. Centered in the tropical lowlands of present-day Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, and southern Mexico, the Maya are renowned for their achievements in writing, astronomy, mathematics, and monumental architecture. The civilization’s intricate socio-political structures and vibrant cultural traditions continue to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike.

The Olmec civilization

The Olmec civilization, often referred to as the ‘mother culture’ of Mesoamerica, flourished in the Gulf Coast region of present-day Mexico between approximately 1500 BCE and 400 BCE. Renowned for their monumental stone heads, intricate art, and foundational cultural contributions, the Olmecs set the stage for subsequent civilizations such as the Maya and Aztecs. Their influence extended far beyond their geographic boundaries, leaving an enduring legacy in Mesoamerican religion, architecture, and societal organization.

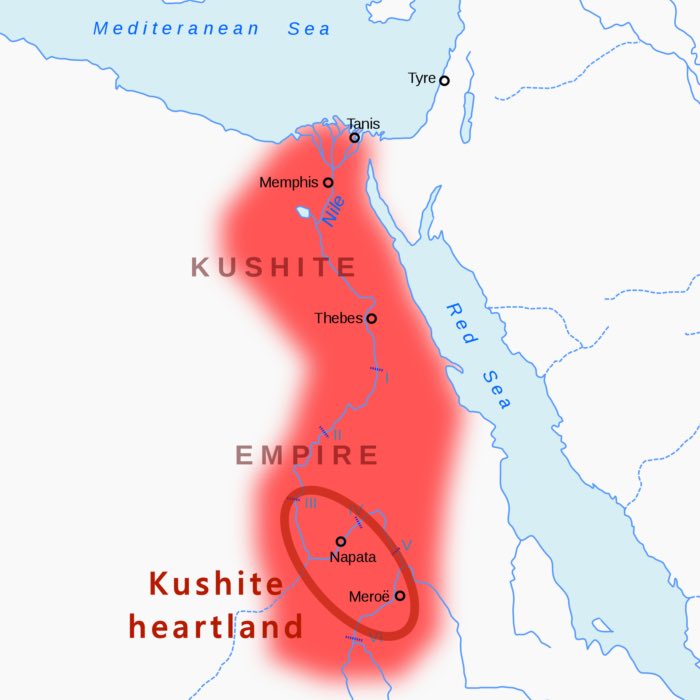

The Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush, flourishing between approximately 1070 BCE and 350 CE, was a major civilization in northeastern Africa, centered in what is now modern-day Sudan. Positioned along the Nile River, Kush played a pivotal role in regional politics, trade, and culture, often interacting with its more famous northern neighbor, Egypt. Renowned for its wealth, monumental architecture, and artistic achievements, the Kingdom of Kush is one of Africa’s great early civilizations, demonstrating the sophistication and interconnectedness of ancient African societies.

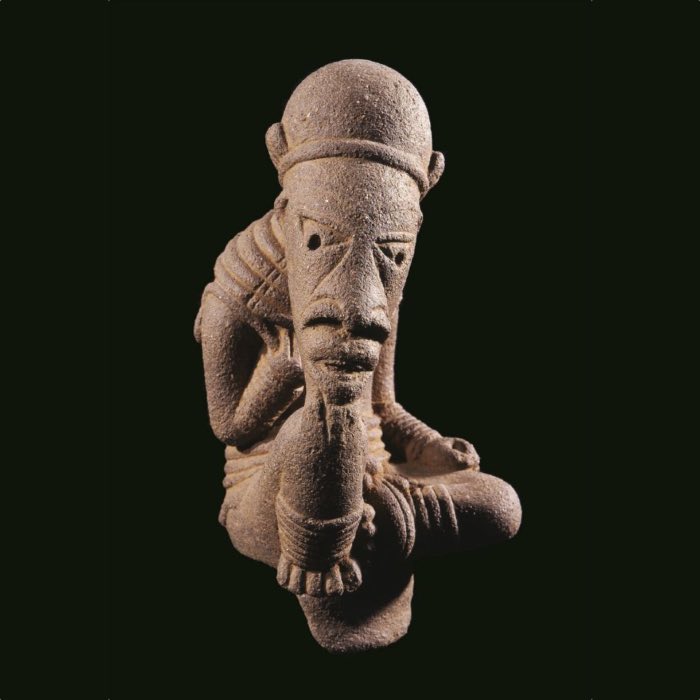

The Nok culture

The Nok culture, flourishing in present-day Nigeria from approximately 1000 BCE to 300 CE, is one of the earliest known complex societies in sub-Saharan Africa. Renowned for its distinctive terracotta sculptures and early ironworking, the Nok culture represents a significant chapter in African history. Its cultural and technological achievements influenced later West African civilizations, laying the foundation for complex societies in the region.