Momotarō at Schloss Arenfels – A Japanese fairy tale in light and stone

Schloss Arenfels, a historic castle near Bad Hönningen in Rheinland-Pfalz (Rhineland-Palatinate), recently hosted a remarkable cultural event that bridged Japanese folklore, contemporary light art, and European historical architecture. The famous Japanese fairy tale Momotarō, often known as Peach Boy, became the centerpiece of an immersive light installation that turned the facade and interior rooms of the castle into a living canvas. Through the interplay of light, projection, and spatial design, visitors were invited not only to see the story but to step into it, experiencing it as a visual journey. Luckily, I had the chance to visit this unique event and experience the fusion of storytelling, technology, and cultural exchange firsthand.

The illuminated front facade of Schloss Arenfels.

The illuminated front facade of Schloss Arenfels.

A story told through light and space

The tale of Momotarō, first fully documented in the Edo period (1603-1868), remains one of Japan’s most iconic folk tales. It tells of an elderly, childless couple who discover a giant peach floating down the river. When they cut it open, they find a baby boy inside – a divine gift who will bring them happiness and honor. As the boy grows, his strength and sense of justice set him apart. When Momotarō learns that a band of Oni (demonic ogres) has been terrorizing nearby villages, he vows to defeat them and restore peace.

The illuminated facade of the main building seen from the inner courtyard.

The illuminated facade of the main building seen from the inner courtyard.

Armed with kibi dango (millet dumplings), a symbol of nourishment and sharing, Momotarō embarks on his quest. Along the way, he befriends a dog, a monkey, and a pheasant, who join him after receiving dumplings as a token of friendship. Together, they sail to Onigashima, the Oni’s island stronghold. After a fierce battle, they defeat the demons, recover stolen treasures, and return home as heroes.

At Schloss Arenfels, this legendary hero’s journey was retold through hi-res light projection mapping directly onto the outer walls of the castle. The medieval stonework served as both screen and symbolic landscape, merging the ancient Japanese narrative with the physical reality of the European fortress. Visitors arriving after dusk were greeted by the floating narration, drifting across the textured walls like a visual haiku, blending light, nature, and story into a single aesthetic statement.

As the projection unfolded, central scenes of Momotarō’s tale appeared one by one, rendered in vivid, almost ukiyo-e inspired designs, yet dynamically animated to follow the architectural contours of the castle itself. The climactic battle at Onigashima transformed the castle into a flaming Oni fortress, where shadows of combatants flickered across towers and archways, bridging traditional Japanese imagery with the spatial and historical presence of the European building.

Momotarō’s journey to Onigashima projected onto the facade.

Momotarō’s journey to Onigashima projected onto the facade.

The passage over the sea to Onigashima.

The passage over the sea to Onigashima.

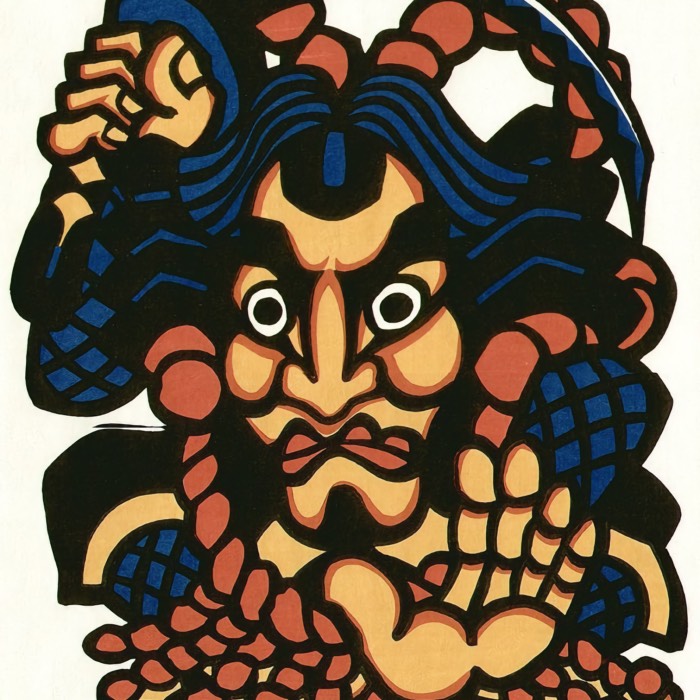

Momotarō’s fight against the Oni.

Momotarō’s fight against the Oni.

Momotarō’s fight against the Oni.

Momotarō’s fight against the Oni.

Momotarō finally defeats the Oni.

Momotarō finally defeats the Oni.

Interior installations – storytelling across rooms

Inside the castle, the immersive experience continued. Several rooms were transformed into themed environments, each evoking a particular scene or mood from the story:

Wooden sculpture of a Roman soldier.

Wooden sculpture of a Roman soldier.

The historical staircase of the castle, meticulously decorated with Chinese lanterns.

The historical staircase of the castle, meticulously decorated with Chinese lanterns.

Another view of the historical steel staircase.

Another view of the historical steel staircase.

A portrait (unknown) in the interior of Schloss Arenfels.

A portrait (unknown) in the interior of Schloss Arenfels.

A porcelain figure, embedded in the decoration for the event.

A porcelain figure, embedded in the decoration for the event.

A room with a chimney, set up for the atmosphere of the event.

A room with a chimney, set up for the atmosphere of the event.

Another room set up for the event.

Another room set up for the event.

Porcelain with Chinese motifs was part of the table decoration on one of the rooms.

Porcelain with Chinese motifs was part of the table decoration on one of the rooms.

Wallpaper with Chinese motifs.

Wallpaper with Chinese motifs.

The coat of arms of the family of the castle’s owner, flooded with red light from a light show in the same room.

The coat of arms of the family of the castle’s owner, flooded with red light from a light show in the same room.

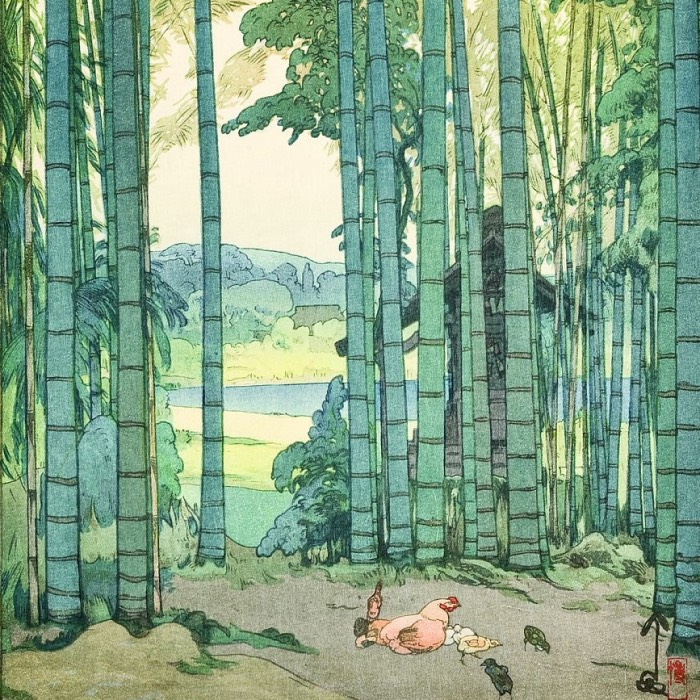

One room glowed in the light of the colorful projections narrating Momotarō’s discovery and childhood:

In one room, colorful drawings projected onto a wall niche narrated the story of Momotarō’s discovery by the old couple and his childhood under their care.

In one room, colorful drawings projected onto a wall niche narrated the story of Momotarō’s discovery by the old couple and his childhood under their care.

Momotarō’s discovery in the giant peach.

Momotarō’s discovery in the giant peach.

The old couple takes care of Momotarō.

The old couple takes care of Momotarō.

Momotarō grew up to under the care of his adoptive parents.

Momotarō grew up to under the care of his adoptive parents.

Momotarō grew up to under the care of his adoptive parents.

Momotarō grew up to under the care of his adoptive parents.

Momotarō learns the martial arts.

Momotarō learns the martial arts.

Momotarō decides to leave his parents to fight the Oni.

Momotarō decides to leave his parents to fight the Oni.

Another space plunged visitors into darkness and flickering red shadows, recreating the atmosphere of Onigashima:

Light show in the interior of Schloss Arenfels.

Light show in the interior of Schloss Arenfels.

Light show in the interior of Schloss Arenfels.

Light show in the interior of Schloss Arenfels.

The heroes’ loyalty and courage were reflected in bold projections and subtle symbolic props — from the Oni’s oversized presence to the brave actions of Momotarō and his animal companions:

The giant Oni projected on the walls of the interior of the castle.

The giant Oni projected on the walls of the interior of the castle.

The same room and wall, just a few seconds later, Momotarō fights the Oni. Both, the illuminated tale and the room’s furniture as well as their shadows fuse into a single visual experience.

The same room and wall, just a few seconds later, Momotarō fights the Oni. Both, the illuminated tale and the room’s furniture as well as their shadows fuse into a single visual experience.

The visitors became kind of part of the light show as their shadows were projected on the walls due in the interior of the castle.

The visitors became kind of part of the light show as their shadows were projected on the walls due in the interior of the castle.

These spatial interpretations were not literal retellings, but rather poetic impressions, allowing visitors to experience the emotional landscape of the story rather than merely observing its plot points. This use of immersive design invited a more intuitive, sensory engagement with the material, encouraging visitors to feel the bravery, fear, and triumph embedded in the tale.

Symbolism and moral meaning – more than a fairy tale

While Momotarō is often presented as a children’s story, its deeper symbolism and moral lessons reflect essential elements of Japanese cultural and ethical thought. The peach, for instance, is not merely a plot device but a symbol of life, purity, and supernatural blessing. Momotarō’s sharing of dumplings with his companions highlights the central virtue of generosity and cooperation, essential in Japanese ethical philosophy, where the success of the collective matters more than individual glory.

The Oni, representing chaos, greed, and oppression, are not just monsters — they embody forces that threaten social harmony. Momotarō’s quest is thus a cosmic act of justice, restoring the natural and moral balance between human society and the supernatural world. His filial piety — his desire to protect the village and honor the parents who raised him — reinforces the importance of loyalty to family and community, a key value in Confucian-influenced Japanese culture.

In some historical interpretations, the Oni have also been seen as stand-ins for foreign invaders or pirates, adding a further layer of cultural memory and national defense to the story. Momotarō, in this reading, becomes a defender of the homeland, a motif familiar not only in Japanese legend but in heroic traditions worldwide.

By staging this morally rich narrative within the walls of Schloss Arenfels, the installation subtly suggested that fairy tales across cultures share universal ethical foundations — courage, loyalty, justice, and the eternal confrontation between order and chaos. This transcultural dialogue, expressed through light art, transformed the installation into a meditation on storytelling itself: why we tell stories, how they reflect our values, and how they evolve when retold in new cultural and spatial contexts.

Conclusion

The Momotarō installation at Schloss Arenfels was more than a spectacle of light and color. It was an act of cultural translation, bringing Japanese narrative tradition into conversation with European history and contemporary art technology. The fusion of ancient tale, modern projection mapping, and medieval architecture created a multi-layered cultural artifact, one that encouraged both aesthetic appreciation and reflection on shared human values.

By revisiting this classic fairy tale through the lens of light and space, the installation reminded me of the power of storytelling to transcend borders, connecting us across time and space, and revealing the enduring truths at the heart of all great tales.

References and further reading

- S. Noma, Momotarō, In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia,1993, Kodansha, ISBN: 4-06-931098-X

- Ralph F. McCarthy, Ioe Saito, The Adventure of Momotaro, the Peach Boy, 2000, Kodansha’s Children’s Classics, ISBN: 4-7700-2098-8

- Momotaro - Folk Legends - Kids Web Japan - Web Japanꜛ, Retelling of the saga at Kids Web Japan of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Momotaro: die Geschichte vom Sohn des Pfirsichs. Kindergerechte Nacherzählung der Geschichte auf Deutschꜛ

- Momotaro, der Junge der aus dem Pfirsich kam. Über den Momotaroschrein bei Inuyama, Nagoyaꜛ

- YouTube promo video of the eventꜛ

comments