How the Jewish community of Frankfurt reflects Europe’s complex Jewish history

Throughout European history, Jewish communities have oscillated between periods of relative peace and prosperity and times of persecution, often driven by Christian fanaticism and exclusionary policies. In Germany, Jews contributed significantly to cultural, economic, and intellectual life, despite facing systemic discrimination and violence. The Enlightenment brought gradual emancipation, enabling Jewish communities to integrate more fully into broader society.

“Untitled” by Ariel Schlesinger, sculpture on the forecourt of the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt. The landmark of the new Jewish Museum in Frankfurt is this double tree, which seems to be a reflection of itself. The sculpture draws its inspiration from the history of Frankfurt’s Jews: the feeling of being simultaneously connected and uprooted. At the same time, it goes back to various Jewish sources, such as the Kabbalistic tree of life, which reflects divine creation. Read more about this sculpture on the museum’s websiteꜛ.

“Untitled” by Ariel Schlesinger, sculpture on the forecourt of the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt. The landmark of the new Jewish Museum in Frankfurt is this double tree, which seems to be a reflection of itself. The sculpture draws its inspiration from the history of Frankfurt’s Jews: the feeling of being simultaneously connected and uprooted. At the same time, it goes back to various Jewish sources, such as the Kabbalistic tree of life, which reflects divine creation. Read more about this sculpture on the museum’s websiteꜛ.

I recently visited the Jewish Museumꜛ in Frankfurt, where I had the opportunity to witness this rich history firsthand. The museum’s exhibits, artifacts, and narratives vividly illustrate the resilience and contributions of Frankfurt’s Jewish population across the centuries. In this post, I will briefly summarize the this history along with the museum’s portrayal of this complex and multifaceted story.

Light well of the new Jewish Museumꜛ in Frankfurt. The building is characterized by a striking architectural design that incorporates both historical and modern elements, reflecting the complex history of Frankfurt’s Jewish community.

Light well of the new Jewish Museumꜛ in Frankfurt. The building is characterized by a striking architectural design that incorporates both historical and modern elements, reflecting the complex history of Frankfurt’s Jewish community.

Early Jewish presence in Frankfurt

Jewish life in Frankfurt can be traced back to at least the 12th century. The first documented mention of Jews in the city appears in 1150, indicating an established presence in the economic and social culture of medieval Frankfurt. Like elsewhere in Christian Europe, Jews were subject to restrictions, forced into specific trades, and periodically targeted by violence.

Top: Excavation of the Judengasse in Frankfurt, now part of the Jewish Museumꜛ. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). – Bottom: The arched Judengasse on a city view by Matthäus Merian from 1628. The square at the southern end is the Judenmarkt. On the right, there is the cemetery. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

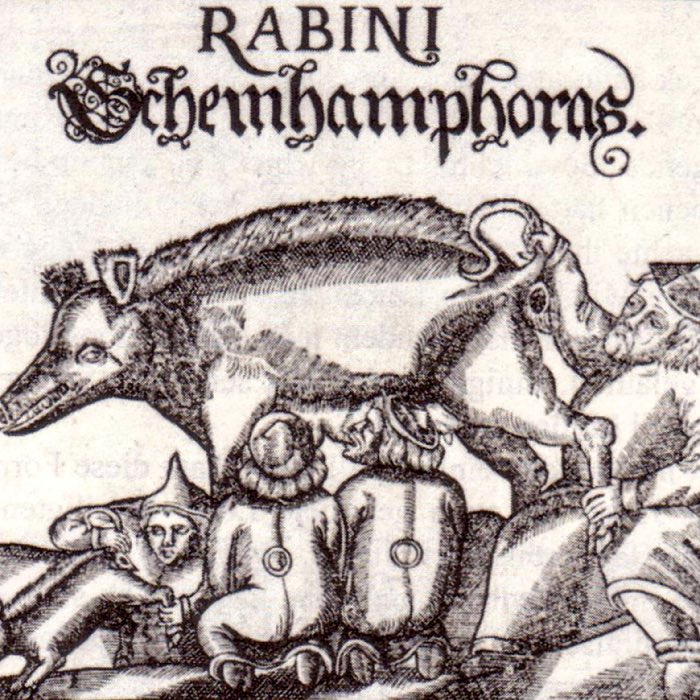

One of the earliest major tragedies unfolded 145 years after the horrific pogroms in the Rhineland of 1096. In 1241, a devastating pogrom culminated in the massacre of a significant portion of the Jewish community—an event grimly remembered as Judenschlachten (“Slaughter of Jews”). Another pogrom took place in 1349, and during the Fettmilch Uprising of 1614–1616, the Jewish community was again violently expelled from Frankfurt. Despite such persecutions, Jews played an essential role in the city’s economy, particularly in finance, trade, and moneylending—activities often imposed on them due to Christian restrictions on usury.

The anti-semitic looting of Frankfurt’s Judengasse during the Fettmilch Uprising 1614–1616. Engraving by Matthäus Merian from 1628. The uprise was a revolt of the guilds and the urban poor against the patricians and the Jewish community. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

By the 15th century, Jews in Frankfurt were confined to the Judengasse, the city’s Jewish ghetto. Established in 1462, this enclosed area became both a site of oppression and a vibrant center of Jewish culture and commerce. The Judengasse saw the growth of prominent families, such as the Rothschilds, and was home to scholars, merchants, and religious leaders. However, repeated outbreaks of anti-Jewish violence, including expulsions and ghetto fires, underscored the precariousness of Jewish life.

Frankfurt Judengasse around 1868. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Changes during the Enlightenment

The 18th century ushered in a new era for Frankfurt’s Jews, driven by the intellectual currents of the Enlightenment and the gradual erosion of Christian exclusivity in civic life. The Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, encouraged the integration of Jewish communities into European society through secular education and economic diversification.

Westend Synagogue in 2008. The Westend Synagogue was built in 1908-1010 and is the largest synagogue in Frankfurt. It was the only one of the former four large synagogues to survive the November pogroms of 1938 and the bombing raids of the Second World War. Until the demise of Jewish life in Frankfurt during the Nazi era, it served as a place of worship for the liberal Reform wing. It was reconsecrated in 1950 after provisional renovation and faithfully restored from 1989 to 1994. After the ghetto was abolished in 1806, the wealthy among Frankfurt’s Jews left the former Judengasse with its cramped, unsanitary living conditions. From around 1860, many who considered themselves part of the liberal bourgeoisie moved to the newly developed Westend. The synagogue was built in Art Nouveau style with Assyrian-Egyptian echoes, designed by architect Franz Roeckle, a later member of the NSDAP. The building of the synagogue illustrates the self-confidence and integration of the Jewish community in Frankfurt at the beginning of the 20th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Judenedikt of 1811, issued by Grand Duke Karl Theodor von Dalberg, granted Jews in Frankfurt increased civil rights, allowing them to participate more fully in the city’s commercial and intellectual life. Though full equality was still a distant goal, Jewish individuals gained access to professions beyond finance, and the community began engaging in broader German cultural and political movements. The emancipation process, however, remained slow and uneven, with residual prejudices manifesting in political debates and social interactions.

Old photos of a synagogue, most likely the Westend Synagogue in Frankfurt.

Old photos of a synagogue, most likely the Westend Synagogue in Frankfurt.

Old photos of a synagogue, most likely the Westend Synagogue in Frankfurt.

Old photos of a synagogue, most likely the Westend Synagogue in Frankfurt.

The Rothschilds and economic contributions

Among the most influential Jewish families in Frankfurt’s history, the Rothschilds epitomize the transformative impact of Jewish economic participation. Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812) founded a banking dynasty from the Judengasse, leveraging a vast network of international finance to become one of Europe’s most powerful economic forces.

Salomon Mayer von Rothschild (1774-1855), by Wilhelm Heinrich Schlesinger (1814-1893), Austria, Vienna, 1838, Oil on canvas. Salomon Mayer von Rothschild opened the S. M. von Rothschild bank in Vienna in 1820. He established close business ties with the emperor and with Klemens von Metternich, the most influential politician of the day. Under Salomon’s leadership, the Rothschild family also began financing industrial enterprises. They were involved in railway construction, mines, the iron industry, and the extraction of raw materials. Salomon von Rothschild was also responsible for the elevation of the family to nobility. Nevertheless, as a Jew, he was not allowed to own property in the city. He rented an entire hotel for his wife, Caroline Stern, and their two children.

Salomon Mayer von Rothschild (1774-1855), by Wilhelm Heinrich Schlesinger (1814-1893), Austria, Vienna, 1838, Oil on canvas. Salomon Mayer von Rothschild opened the S. M. von Rothschild bank in Vienna in 1820. He established close business ties with the emperor and with Klemens von Metternich, the most influential politician of the day. Under Salomon’s leadership, the Rothschild family also began financing industrial enterprises. They were involved in railway construction, mines, the iron industry, and the extraction of raw materials. Salomon von Rothschild was also responsible for the elevation of the family to nobility. Nevertheless, as a Jew, he was not allowed to own property in the city. He rented an entire hotel for his wife, Caroline Stern, and their two children.

The Rothschilds not only contributed to Frankfurt’s economy but also played a crucial role in funding European governments, industrial ventures, and philanthropic initiatives. Their financial success enabled them to support Jewish institutions and champion causes related to Jewish emancipation. By the 19th century, their influence had extended far beyond Frankfurt, yet their origins in the city’s Jewish quarter underscored the community’s economic resilience and adaptability.

Order awarded to Mayer Carl von Rothschild (1820-1886): Belgium, Germany, Denmark, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Austria, Romania, Russia, Sweden, Spain, Turkey, 19th century, silver, partly gold, enamel, textile. Examples like these illustrate the integration, acceptance and recognition of the Jewish community in the 19th century.

Order awarded to Mayer Carl von Rothschild (1820-1886): Belgium, Germany, Denmark, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Austria, Romania, Russia, Sweden, Spain, Turkey, 19th century, silver, partly gold, enamel, textile. Examples like these illustrate the integration, acceptance and recognition of the Jewish community in the 19th century.

Inscription of the Carl V. Rothschild Public Library, which was founded in 1887 by Baroness Louise V. Rothschild. The inscription reads: “1893 Transformed into a permanent foundation by Baroness Carl V. Rothschild and her daughters 1895 Relocated to this house which the V. Rothschild family had occupied. In 1906, Baroness Salomon V. Rothschild, Lady Rothschild, and Baroness James V. Rothschild donated the after Barhaus (?) with the provision that the institution should remain permanently at this location.” The engagement of the Rothschild family in cultural and educational initiatives reflects their commitment to the welfare of the Jewish community and broader society.

Inscription of the Carl V. Rothschild Public Library, which was founded in 1887 by Baroness Louise V. Rothschild. The inscription reads: “1893 Transformed into a permanent foundation by Baroness Carl V. Rothschild and her daughters 1895 Relocated to this house which the V. Rothschild family had occupied. In 1906, Baroness Salomon V. Rothschild, Lady Rothschild, and Baroness James V. Rothschild donated the after Barhaus (?) with the provision that the institution should remain permanently at this location.” The engagement of the Rothschild family in cultural and educational initiatives reflects their commitment to the welfare of the Jewish community and broader society.

Cultural and intellectual flourishing

The 19th and early 20th centuries marked a golden era of Jewish cultural and intellectual life in Frankfurt. The Jewish community produced influential thinkers, writers, and scholars who shaped both Jewish and broader European thought.

Key figures included Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, a leader of modern Orthodox Judaism, and philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, whose existential and theological writings remain central to Jewish thought. Jewish publishers and intellectuals contributed to Frankfurt’s status as a hub of literary and philosophical discourse, participating in both Jewish and secular spheres of knowledge.

Jewish newspapers, salons, and cultural associations fostered a vibrant exchange of ideas, illustrating the integration of Jewish intellectuals into German cultural life while maintaining a distinct Jewish identity.

Meorot. Magazine of the Zionist Youth of Germany, Volume 26, No place given, 1970.

Meorot. Magazine of the Zionist Youth of Germany, Volume 26, No place given, 1970.

Zedaka box of the Keren Kajemet LeJisrael (KKL), Berlin, around 1930, non-ferrous metal, rolled, sawn, covered with printed leather. The Keren Kajemet Lefisrael, also known as the Jewish National Fund, was founded in 1901. Its purpose was to collect donations for the purchase of land in Erez Israel, the British Mandate, now Israel, in order to create a national home for Jews. To this end, the fund set up collection boxes in public and private places. These were usually simple blue or white cans. This one is more elaborately designed. The book-like shape and leather cover mimic the “Golden Books” of the KKL, in which all donations to the organization were recorded.

Zedaka box of the Keren Kajemet LeJisrael (KKL), Berlin, around 1930, non-ferrous metal, rolled, sawn, covered with printed leather. The Keren Kajemet Lefisrael, also known as the Jewish National Fund, was founded in 1901. Its purpose was to collect donations for the purchase of land in Erez Israel, the British Mandate, now Israel, in order to create a national home for Jews. To this end, the fund set up collection boxes in public and private places. These were usually simple blue or white cans. This one is more elaborately designed. The book-like shape and leather cover mimic the “Golden Books” of the KKL, in which all donations to the organization were recorded.

Another Zedaka box, Denmark, Copenhagen, 1901 Pewter, cast, engraved.

Another Zedaka box, Denmark, Copenhagen, 1901 Pewter, cast, engraved.

“Anti-Anit – Tatsachen zur Judenfrage”. This loose-leaf collection, first printed in 1924, was outstanding with seven editions and 40,000 printed copies. It was intended to provide factual information about the Jewish question and to counteract anti-Semitic propaganda. The collection was published by the Philo-Verlagꜛ, which was founded in 1919 by the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith and was forcibly closed in Nazi Germany in 1938.

“Anti-Anit – Tatsachen zur Judenfrage”. This loose-leaf collection, first printed in 1924, was outstanding with seven editions and 40,000 printed copies. It was intended to provide factual information about the Jewish question and to counteract anti-Semitic propaganda. The collection was published by the Philo-Verlagꜛ, which was founded in 1919 by the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith and was forcibly closed in Nazi Germany in 1938.

Religious life and institutions

Frankfurt was home to a diverse Jewish religious landscape, ranging from traditional Orthodox communities to Reform and Liberal movements. The city saw the development of institutions that shaped modern Judaism, including the Hirschian Neo-Orthodoxy movement and significant contributions to Reform Judaism.

Synagogues such as the Westend Synagogue and educational institutions provided spaces for religious practice and scholarly study. Despite differences in observance and ideology, Frankfurt’s Jews maintained a dynamic religious life that accommodated various theological perspectives.

Babylonian Talmud, Frankfurt am Main, 1715/16, According to tradition, Moses received a written and an oral Torah at Sinai. The written Torah comprises the five books of Moses. The oral Torah, the rabbinical discussions about the commandments and their interpretations, was written down around 200 CE and edited and canonized as the Mishnah in Hebrew. It forms the central text of the Talmud and is commented on, discussed and supplemented by another text, the Gemara, in Aramaic. The Gemara also contains stories, anecdotes and parables. The dialogical and dynamic character of the Talmud is also reflected in the layout of the text pages: the Mishnah and Gemara are in the middle, with later commentaries and discussions in the margins.

Babylonian Talmud, Frankfurt am Main, 1715/16, According to tradition, Moses received a written and an oral Torah at Sinai. The written Torah comprises the five books of Moses. The oral Torah, the rabbinical discussions about the commandments and their interpretations, was written down around 200 CE and edited and canonized as the Mishnah in Hebrew. It forms the central text of the Talmud and is commented on, discussed and supplemented by another text, the Gemara, in Aramaic. The Gemara also contains stories, anecdotes and parables. The dialogical and dynamic character of the Talmud is also reflected in the layout of the text pages: the Mishnah and Gemara are in the middle, with later commentaries and discussions in the margins.

Circumcision set in velvet case, Czech Republic, after 1848 Silver, steel, wood, velvet.

Circumcision set in velvet case, Czech Republic, after 1848 Silver, steel, wood, velvet.

Signs showing honorable duties during the service, Frankfurt am Main, around 1906, wood, velvet, gilded silver. Jewish worship services center on a reading from the Torah, which is kept in a Torah ark in the syna-gogue. Congregation members are responsible for removing the Torah scroll from the ark, carrying it to the reading desk, and preparing for the reading. Members of Frankfurt’s neo-Orthodox congregation were given one of these silver plaques to perform this task. At the time, members of the neo-Orthodox congregation could purchase especially honorable holiday duties by auction. The proceeds went to charitable causes. The Liberal congregation, however, regarded auctions during services as inappropriate and thus rejected the practice.

Signs showing honorable duties during the service, Frankfurt am Main, around 1906, wood, velvet, gilded silver. Jewish worship services center on a reading from the Torah, which is kept in a Torah ark in the syna-gogue. Congregation members are responsible for removing the Torah scroll from the ark, carrying it to the reading desk, and preparing for the reading. Members of Frankfurt’s neo-Orthodox congregation were given one of these silver plaques to perform this task. At the time, members of the neo-Orthodox congregation could purchase especially honorable holiday duties by auction. The proceeds went to charitable causes. The Liberal congregation, however, regarded auctions during services as inappropriate and thus rejected the practice.

Torah shield with oak leaves and palm branches, E. Schürmann & Co., Frankfurt am Main, around 1875 Silver, chased, partially gilded. The visible details on this Torah shield are very expressive. At the bottom, a wreath surrounds the tablets of the Ten Commandments, consisting of ‘German’ oak leaves and ‘Jewish’ palm leaves. palm leaves. This sign was used by the liberal community in Frankfurt in their main synagogue. The members of the congregation defined themselves as German citizens of the Jewish faith. They therefore dispensed with the centuries-old prayers requesting a return to Israel in their liturgy. The followers of neo-orthodoxy, on the other hand, retained these prayers, but understood them as an expression of religious longing.

Torah shield with oak leaves and palm branches, E. Schürmann & Co., Frankfurt am Main, around 1875 Silver, chased, partially gilded. The visible details on this Torah shield are very expressive. At the bottom, a wreath surrounds the tablets of the Ten Commandments, consisting of ‘German’ oak leaves and ‘Jewish’ palm leaves. palm leaves. This sign was used by the liberal community in Frankfurt in their main synagogue. The members of the congregation defined themselves as German citizens of the Jewish faith. They therefore dispensed with the centuries-old prayers requesting a return to Israel in their liturgy. The followers of neo-orthodoxy, on the other hand, retained these prayers, but understood them as an expression of religious longing.

Ner Tamid, Austria, Mattersdorf, around 1840, silver.

Ner Tamid, Austria, Mattersdorf, around 1840, silver.

Hanukkah candlestick with music box, Germany, 1890-1920 White metal with musical mechanism. Hanukkah means consecration. The festival is celebrated in December and lasts eight days. It commemorates the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem over 2000 years ago. Hanukkah is primarily a domestic festival. The eight-branched candelabra is lit immediately after dark, with one more candle lit each day. Games, presents for the children and songs accompany the celebration. This Hanukkah candlestick has a music box in its base that plays the song ‘Maos Zur’ (Rock of my Salvation). It is a traditional and very well-known song for Hanukkah.

Hanukkah candlestick with music box, Germany, 1890-1920 White metal with musical mechanism. Hanukkah means consecration. The festival is celebrated in December and lasts eight days. It commemorates the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem over 2000 years ago. Hanukkah is primarily a domestic festival. The eight-branched candelabra is lit immediately after dark, with one more candle lit each day. Games, presents for the children and songs accompany the celebration. This Hanukkah candlestick has a music box in its base that plays the song ‘Maos Zur’ (Rock of my Salvation). It is a traditional and very well-known song for Hanukkah.

Wine jug and wine cup for traveling, France, around 1900, glass in silver frame with inscription. This jug and cup for wine, which is drunk at the beginning of the Sabbath or on a holiday, comes with a casket. They can be taken anywhere in it. Because even those who are not at home on Shabbat or another holiday should observe the feast day. The ceremony associated with drinking the wine is called Kiddush. The person performing the Kiddush fills the cup with red wine and says a blessing before drinking it. Everyone present then also takes a sip of wine.

Wine jug and wine cup for traveling, France, around 1900, glass in silver frame with inscription. This jug and cup for wine, which is drunk at the beginning of the Sabbath or on a holiday, comes with a casket. They can be taken anywhere in it. Because even those who are not at home on Shabbat or another holiday should observe the feast day. The ceremony associated with drinking the wine is called Kiddush. The person performing the Kiddush fills the cup with red wine and says a blessing before drinking it. Everyone present then also takes a sip of wine.

Kiddush goblet, from left to right: Silberwarenfabrik Adolf G. Meyer, Frankfurt am Main, 1926, silver, pressed from the model, engraved, hallmarked, partially gilded; Mang Hopfer (d. 1694), Augsburg, mid-17th century, silver, cast, engraved, hallmarked, engraved inscription; Frankfurt am Main, 1924 silver, hallmarked, engraved monogram: PB (Paul Bloch).

Kiddush goblet, from left to right: Silberwarenfabrik Adolf G. Meyer, Frankfurt am Main, 1926, silver, pressed from the model, engraved, hallmarked, partially gilded; Mang Hopfer (d. 1694), Augsburg, mid-17th century, silver, cast, engraved, hallmarked, engraved inscription; Frankfurt am Main, 1924 silver, hallmarked, engraved monogram: PB (Paul Bloch).

Hanukkah candlestick, Lazarus Posen Witwe silverware factory, Frankfurt am Main, early 20th century, silver. This Hanukkah candlestick comes from the Frankfurt silverware factory Lazarus Posen Witwe. Brendina Posen continued her husband’s business under this name from 1869. Her wares were considered extremely elegant, durable and stylish. European courts and wealthy, fashion-conscious customers ordered their silverware from her. During the pogrom night of November 9, 1938, the National Socialists destroyed the two stores in Frankfurt and Berlin. The owners of the company, grandsons of the founder, fled to the USA and Israel, where they produced high-quality silverware until their deaths.

Hanukkah candlestick, Lazarus Posen Witwe silverware factory, Frankfurt am Main, early 20th century, silver. This Hanukkah candlestick comes from the Frankfurt silverware factory Lazarus Posen Witwe. Brendina Posen continued her husband’s business under this name from 1869. Her wares were considered extremely elegant, durable and stylish. European courts and wealthy, fashion-conscious customers ordered their silverware from her. During the pogrom night of November 9, 1938, the National Socialists destroyed the two stores in Frankfurt and Berlin. The owners of the company, grandsons of the founder, fled to the USA and Israel, where they produced high-quality silverware until their deaths.

Hanukkah candlestick, Germany, 1920-1930 Brass, silver-plated.

Hanukkah candlestick, Germany, 1920-1930 Brass, silver-plated.

Shabbat candlestick, Berlin, 1820s, silver, chased, cast, hallmarked. The Shabbat begins on Friday evening. To welcome it and mark the beginning of the weekly holiday, two candles are lit to a blessing. This ritual is traditionally the task of a woman in the family. These two silver Shabbat candlesticks are marked with the abbreviation H. St., which is engraved in Latin letters on the base plate. The initials stand for Henriette Steinhausen, to whom these candlesticks belonged. Her granddaughter Rose Steinhausen donated the two chandeliers to the museum. Classicist chandeliers like these have been used since around 1800 and are still popular today.

Shabbat candlestick, Berlin, 1820s, silver, chased, cast, hallmarked. The Shabbat begins on Friday evening. To welcome it and mark the beginning of the weekly holiday, two candles are lit to a blessing. This ritual is traditionally the task of a woman in the family. These two silver Shabbat candlesticks are marked with the abbreviation H. St., which is engraved in Latin letters on the base plate. The initials stand for Henriette Steinhausen, to whom these candlesticks belonged. Her granddaughter Rose Steinhausen donated the two chandeliers to the museum. Classicist chandeliers like these have been used since around 1800 and are still popular today.

Besamim towers, Lazarus Posen Witwe silverware factory, Frankfurt am Main, around 1910, silver, cast from the model, chased, engraved, partially gilded. At the end of the Shabbat day of rest, the ceremony of the Havdala is performed: it marks the end of the holy time and the beginning of the secular week. The ceremony consists of a blessing over a glass of wine, the lighting of a candle with a flaming light and the smell of aromatic spices such as cloves. Theophile Jacob and his wife donated one of these Besamim towers (left) to their community in Sarrebourg, France, in 1909/10. The Hawdala ceremony is not only celebrated privately, but also in the synagogue. The Besamim tower comes from the art trade. It is not clear whether it was stolen from the synagogue during the Nazi era or sold into the trade from private ownership.

Besamim towers, Lazarus Posen Witwe silverware factory, Frankfurt am Main, around 1910, silver, cast from the model, chased, engraved, partially gilded. At the end of the Shabbat day of rest, the ceremony of the Havdala is performed: it marks the end of the holy time and the beginning of the secular week. The ceremony consists of a blessing over a glass of wine, the lighting of a candle with a flaming light and the smell of aromatic spices such as cloves. Theophile Jacob and his wife donated one of these Besamim towers (left) to their community in Sarrebourg, France, in 1909/10. The Hawdala ceremony is not only celebrated privately, but also in the synagogue. The Besamim tower comes from the art trade. It is not clear whether it was stolen from the synagogue during the Nazi era or sold into the trade from private ownership.

Besamim box, Emestus Römer (d. 1744), Hanau, mid-18th century, silver, embossed.

Besamim box, Emestus Römer (d. 1744), Hanau, mid-18th century, silver, embossed.

Etrog bowl, Felix Horovitz silver workshop (1877-1928), Frankfurt am Main, around 1904, silver, sand model casting, polished, engraved. The seven-day festival of Sukkot in the fall commemorates the Israelites’ wandering in the desert after their exodus from Egypt. According to tradition, it is accompanied by the waving of a festive bouquet. It consists of branches of palm trees, myrtle and willow as well as the etrog. This citrus fruit may only be used undamaged. It is therefore kept in a special bowl. According to its inscription, the bowl shown here was donated to the Börneplatz synagogue in Frankfurt. In ancient times, Sukkot was celebrated with a pilgrimage to the temple and the festive bouquets were laid around the altar there on the last day. The engraved willow branches on the silver bowl are a reminder of this.

Etrog bowl, Felix Horovitz silver workshop (1877-1928), Frankfurt am Main, around 1904, silver, sand model casting, polished, engraved. The seven-day festival of Sukkot in the fall commemorates the Israelites’ wandering in the desert after their exodus from Egypt. According to tradition, it is accompanied by the waving of a festive bouquet. It consists of branches of palm trees, myrtle and willow as well as the etrog. This citrus fruit may only be used undamaged. It is therefore kept in a special bowl. According to its inscription, the bowl shown here was donated to the Börneplatz synagogue in Frankfurt. In ancient times, Sukkot was celebrated with a pilgrimage to the temple and the festive bouquets were laid around the altar there on the last day. The engraved willow branches on the silver bowl are a reminder of this.

Torah curtain, Germany, 1866, rust-red velvet, metal thread embroidery, appliquéd sequins, brocade fabric, metal fringes made of silver wire. A Torah curtain hangs in front of the Torah shrine. The motifs on this curtain refer to central elements of the temple: the Ark of the Covenant, in which the tablets of the law were kept, can be seen in the middle. The two pillars are reminiscent of the entrance to the temple. The seven-branched temple candlestick and the table of showbread can be seen on them. These motifs emphasize the connection between the Temple and the synagogue service: the Holy of Holies of the Temple with the Ark of the Covenant is symbolically linked to the Torah shrine in the synagogue. The curtain is adorned with a crown inscribed with ‘Crown of the Torah’. This curtain was donated by the ‘Society of the Holy Vestments’. In the Bible, the term ‘holy garments’ also refers to the clothing of the priests. This establishes a further relationship between the temple and the synagogue.

Torah curtain, Germany, 1866, rust-red velvet, metal thread embroidery, appliquéd sequins, brocade fabric, metal fringes made of silver wire. A Torah curtain hangs in front of the Torah shrine. The motifs on this curtain refer to central elements of the temple: the Ark of the Covenant, in which the tablets of the law were kept, can be seen in the middle. The two pillars are reminiscent of the entrance to the temple. The seven-branched temple candlestick and the table of showbread can be seen on them. These motifs emphasize the connection between the Temple and the synagogue service: the Holy of Holies of the Temple with the Ark of the Covenant is symbolically linked to the Torah shrine in the synagogue. The curtain is adorned with a crown inscribed with ‘Crown of the Torah’. This curtain was donated by the ‘Society of the Holy Vestments’. In the Bible, the term ‘holy garments’ also refers to the clothing of the priests. This establishes a further relationship between the temple and the synagogue.

Sefirat haOmer, book for counting the Omer with illustrations, Offenbach am Main, 1804/05. This booklet contains prayers for the 49 days between Passover and Shavuot. From Passover onwards, each day is ritually counted. At the time of the Temple, a sacrifice was made in the Temple on the first of these 49 days from the new harvest, called the Omer after an ancient measure of grain. Today, the ritual counting commemorates the loss of the temple and other catastrophes in Jewish history. In traditional circles, it is therefore customary to observe certain mourning rules. For example, no weddings are celebrated, people do not shave and do not have their hair cut. This is only permitted on the 33rd day - as can be clearly seen on the woodcut in the booklet.

Sefirat haOmer, book for counting the Omer with illustrations, Offenbach am Main, 1804/05. This booklet contains prayers for the 49 days between Passover and Shavuot. From Passover onwards, each day is ritually counted. At the time of the Temple, a sacrifice was made in the Temple on the first of these 49 days from the new harvest, called the Omer after an ancient measure of grain. Today, the ritual counting commemorates the loss of the temple and other catastrophes in Jewish history. In traditional circles, it is therefore customary to observe certain mourning rules. For example, no weddings are celebrated, people do not shave and do not have their hair cut. This is only permitted on the 33rd day - as can be clearly seen on the woodcut in the booklet.

Torah scroll from the Baumweg Synagogue, Germany, 20th century, parchment, rolled onto wooden sticks.

Torah scroll from the Baumweg Synagogue, Germany, 20th century, parchment, rolled onto wooden sticks.

Everyday life and challenges of assimilation

The growing acceptance of Jews into German society brought both opportunities and tensions. Many Jewish families sought to assimilate by adopting German customs, names, and languages, while others struggled to balance integration with preserving Jewish traditions.

Intermarriage, secularization, and participation in German nationalism complicated Jewish identity. The push for assimilation was met with persistent anti-Semitic sentiments, reminding Jewish citizens that their acceptance remained conditional in many spheres of life.

Moses with the Ten Commandments Munich, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), 1817/18, Oil on canvas. This painting presents the founding figure of the Jewish tradition. A comparatively young Moses is pointing to the Hebrew-inscribed tablets with the Ten Commandments. Moses is depicted as a teacher explaining the word of God. The tents in the background allude to the Israelites’ journey through the wilderness, led by Moses. In his memoirs, Oppenheim wrote: ‘The first painting that I composed was of Moses, life-size; I presented him in toga-like dress, which Professor Langer disapproved of. He asked me why I did this in this way, and not difjerently? I replied that I did this because it was how I imagined Moses, to which Langer said tenderly, ‘Well, if you know better!’ and left.’ The style and monumental format of the Moses painting correspond to historical painting that frequently turns to Christian motifs, yet Oppenheim adopts this style to Jewish tradition. The self-assured visual idiom of the painting incorporates jewish tradition into a history of art shaped by Christianity.

Moses with the Ten Commandments Munich, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), 1817/18, Oil on canvas. This painting presents the founding figure of the Jewish tradition. A comparatively young Moses is pointing to the Hebrew-inscribed tablets with the Ten Commandments. Moses is depicted as a teacher explaining the word of God. The tents in the background allude to the Israelites’ journey through the wilderness, led by Moses. In his memoirs, Oppenheim wrote: ‘The first painting that I composed was of Moses, life-size; I presented him in toga-like dress, which Professor Langer disapproved of. He asked me why I did this in this way, and not difjerently? I replied that I did this because it was how I imagined Moses, to which Langer said tenderly, ‘Well, if you know better!’ and left.’ The style and monumental format of the Moses painting correspond to historical painting that frequently turns to Christian motifs, yet Oppenheim adopts this style to Jewish tradition. The self-assured visual idiom of the painting incorporates jewish tradition into a history of art shaped by Christianity.

Mourning Jews in Exile, by Eduard Bendemann (1811-1889), After 1832, Oil on canvas. Eduard Bendemann was christened as a child. Nevertheless, he painted motifs from Jewish tradition in the Nazarene style of historical art, just like Moritz Daniel Oppenheim. This painting presents a dramatic event in Jewish history: in 586 BC, the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem and abducted the population. A quote from Psalm 137 - ‘By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept, when we remembered Zion’ - was originally on the frame. ‘Mourning Jews in Exile’ is Bendemann’s best-known work. It exists in multiple versions, one of which is this painting. The work also achieved broad distribution in prints.

Mourning Jews in Exile, by Eduard Bendemann (1811-1889), After 1832, Oil on canvas. Eduard Bendemann was christened as a child. Nevertheless, he painted motifs from Jewish tradition in the Nazarene style of historical art, just like Moritz Daniel Oppenheim. This painting presents a dramatic event in Jewish history: in 586 BC, the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem and abducted the population. A quote from Psalm 137 - ‘By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept, when we remembered Zion’ - was originally on the frame. ‘Mourning Jews in Exile’ is Bendemann’s best-known work. It exists in multiple versions, one of which is this painting. The work also achieved broad distribution in prints.

The Rescue of Hagar and Ishmael in the Desert, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Rome, 1826 Oil on wood. This painting shows Abraham’s second wife, Hagar, and their son ishmael, who are banished to the desert upon the request of Abraham’s first wife, Sarah. The image is both an illustration and an interpretation of a biblical story. Beginning in the Letters of Paul, Christian theology understood Sarah as the personification of Christianity and Hagar as the embodiment of Judaism, with the latter having lost its significance. Oppenheim’s painting, however, emphasizes the conciliatory aspect of the story: the outcasts are saved from dying of thirst by the intervention of an angel sent by God. In Islam, Ishmael is considered both a prophet and the progenitor of the Arab peoples.

The Rescue of Hagar and Ishmael in the Desert, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Rome, 1826 Oil on wood. This painting shows Abraham’s second wife, Hagar, and their son ishmael, who are banished to the desert upon the request of Abraham’s first wife, Sarah. The image is both an illustration and an interpretation of a biblical story. Beginning in the Letters of Paul, Christian theology understood Sarah as the personification of Christianity and Hagar as the embodiment of Judaism, with the latter having lost its significance. Oppenheim’s painting, however, emphasizes the conciliatory aspect of the story: the outcasts are saved from dying of thirst by the intervention of an angel sent by God. In Islam, Ishmael is considered both a prophet and the progenitor of the Arab peoples.

Copy of Raphael’s ‘Madonna della Tenda’, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Munich, 1817/18, Oil on canvas. As a student at the Academy of Art in Munich, Oppenheim copied several famous works from the Old Masters, such as the ‘Madonna della tenda’ by Raphael. The image shows Mary with the infant jesus and John the Baptist. If we compare the copy to the original, we notice that Oppenheim’s painting dispenses with the halos around the three figures. Also, John the Baptist’s cross is missing. By eschewing Christian symbols, Oppenheim creates an interfaith version of this Christian scene.

Copy of Raphael’s ‘Madonna della Tenda’, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Munich, 1817/18, Oil on canvas. As a student at the Academy of Art in Munich, Oppenheim copied several famous works from the Old Masters, such as the ‘Madonna della tenda’ by Raphael. The image shows Mary with the infant jesus and John the Baptist. If we compare the copy to the original, we notice that Oppenheim’s painting dispenses with the halos around the three figures. Also, John the Baptist’s cross is missing. By eschewing Christian symbols, Oppenheim creates an interfaith version of this Christian scene.

Self-portrait with his first wife, Adelheid, née Cleve (1800-1836), by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Frankfurt am Main, 1829, Oil on canvas. In this self-portrait, the painter, who had made a name for himself by this time, gazes out with self-assurance at the viewer. His first wife, Adelheid, is seated next to him. Discreet status symbols, such as luxurious clothing, jewelry, and velvet that has apparently been laid down carelessly, underscore the couple’s affiliation with the middle-class society of the city of Frankfurt. The spectacles and the letter indicate that they are educated. The body language of the married couple, turned slightly toward each other, emphasizes their intimacy. The painting’s composition reproduces the contemporary ideal of a romantic marriage.

Self-portrait with his first wife, Adelheid, née Cleve (1800-1836), by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Frankfurt am Main, 1829, Oil on canvas. In this self-portrait, the painter, who had made a name for himself by this time, gazes out with self-assurance at the viewer. His first wife, Adelheid, is seated next to him. Discreet status symbols, such as luxurious clothing, jewelry, and velvet that has apparently been laid down carelessly, underscore the couple’s affiliation with the middle-class society of the city of Frankfurt. The spectacles and the letter indicate that they are educated. The body language of the married couple, turned slightly toward each other, emphasizes their intimacy. The painting’s composition reproduces the contemporary ideal of a romantic marriage.

Left: Baruch Eschwege (1785-1848) as a Military Volunteer Hanau, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), 1817/18, Oil on canvas. This portrait shows Oppenheim’s brother-in-law, Baruch Eschwege, wearing the uniform of the Volunteer Fighters of the Electorate of Hesse. Like many other German Jews, he volunteered for the armed forces to fight in the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon and against Germany’s occupation. Although Napoleon had decreed equality under law for Jews and ensured that the law was applied in the conquered territories, the majority of German Jews viewed the French army as a hostile occupation force. They were dedicated to the Wars of Liberation and the national-liberal uprising associated with it. – Right: Dr. Jakob Weil (1792-1864), by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Frankfurt, 1847, Oil on canvas. Oppenheim painted his portrait of the philologist and journalist Jakob Weil upon a commission from the Masonic Lodge of the Rising Dawn, of which he was a member. Frankfurt’s Jewish intellectuals met in the lodge in the 1830s and 1840s. Jews were not allowed to be members of many other clubs and associations. The painting was seized by the Nazis, later taken to Moscow, and then ended up in East Berlin. It was stored there for years with other ‘abandoned’ art until the search for former owners began. In 2011, the painting was restored to the Masonic Lodge of the Rising Dawn, which donated the work to the Jewish Museumꜛ.

Left: Baruch Eschwege (1785-1848) as a Military Volunteer Hanau, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), 1817/18, Oil on canvas. This portrait shows Oppenheim’s brother-in-law, Baruch Eschwege, wearing the uniform of the Volunteer Fighters of the Electorate of Hesse. Like many other German Jews, he volunteered for the armed forces to fight in the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon and against Germany’s occupation. Although Napoleon had decreed equality under law for Jews and ensured that the law was applied in the conquered territories, the majority of German Jews viewed the French army as a hostile occupation force. They were dedicated to the Wars of Liberation and the national-liberal uprising associated with it. – Right: Dr. Jakob Weil (1792-1864), by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), Frankfurt, 1847, Oil on canvas. Oppenheim painted his portrait of the philologist and journalist Jakob Weil upon a commission from the Masonic Lodge of the Rising Dawn, of which he was a member. Frankfurt’s Jewish intellectuals met in the lodge in the 1830s and 1840s. Jews were not allowed to be members of many other clubs and associations. The painting was seized by the Nazis, later taken to Moscow, and then ended up in East Berlin. It was stored there for years with other ‘abandoned’ art until the search for former owners began. In 2011, the painting was restored to the Masonic Lodge of the Rising Dawn, which donated the work to the Jewish Museumꜛ.

Hanukkah lamp ‘The Five Maccabees’, by Benno Elkan (1877-1960), Frankfurt am Main, around 1925, Bronze. In anti-Semitic images and texts, Jews were typically portrayed as weaklings. In 1898, Max Nordau introduced the concept of the ‘Muskeljude’ or muscled Jew, to counter this perception. With his call for athletic training, he wanted to prepare Jews for the creation of a Jewish state. In the ensuing period, Jewish sports clubs were founded throughout the German Empire, many of which still bear the name "Maccabi" or "Bar Kochba" today, recalling the Jewish rebels of antiquity. The Hanukkah candelabra displayed here, made by Benno Elkan in 1925, shows five of the Maccabees who rose up against the Greeks. They stand for vigor, heroism, and strenth.

Hanukkah lamp ‘The Five Maccabees’, by Benno Elkan (1877-1960), Frankfurt am Main, around 1925, Bronze. In anti-Semitic images and texts, Jews were typically portrayed as weaklings. In 1898, Max Nordau introduced the concept of the ‘Muskeljude’ or muscled Jew, to counter this perception. With his call for athletic training, he wanted to prepare Jews for the creation of a Jewish state. In the ensuing period, Jewish sports clubs were founded throughout the German Empire, many of which still bear the name "Maccabi" or "Bar Kochba" today, recalling the Jewish rebels of antiquity. The Hanukkah candelabra displayed here, made by Benno Elkan in 1925, shows five of the Maccabees who rose up against the Greeks. They stand for vigor, heroism, and strenth.

Stickers with responses to anti-Semites, first third of the 20th century (reproductions). A new mass medium emerged in the late nineteenth century: the sticker. This miniature form of advertising, which was stuck on letters or objects in public space, was used to spread antiSemitic propaganda. In response, the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith and the Jewish communities produced stickers themselves with slogans directed against Jew-hatred. Many made use of quotes from well-known figures. With this form of educational advertising, these Jewish groups attempted to reach as many people as possible. When the Nazis assumed power in 1933, the stickers were banned.

Stickers with responses to anti-Semites, first third of the 20th century (reproductions). A new mass medium emerged in the late nineteenth century: the sticker. This miniature form of advertising, which was stuck on letters or objects in public space, was used to spread antiSemitic propaganda. In response, the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith and the Jewish communities produced stickers themselves with slogans directed against Jew-hatred. Many made use of quotes from well-known figures. With this form of educational advertising, these Jewish groups attempted to reach as many people as possible. When the Nazis assumed power in 1933, the stickers were banned.

The fragile prosperity before 1933

By the early 20th century, Frankfurt’s Jewish community had achieved unprecedented prosperity and influence. Jewish businesses, cultural institutions, and philanthropic initiatives flourished, with Jewish entrepreneurs and intellectuals playing key roles in banking, commerce, and academia. The community actively participated in city life, establishing educational institutions, cultural organizations, and charitable foundations that benefited both Jews and non-Jews alike. However, this prosperity was precarious. Nationalist and anti-Semitic movements, fueled by economic instability and political unrest, increasingly targeted Jewish success, fostering resentment and exclusionary rhetoric. The shadow of systemic discrimination loomed ever larger, foreshadowing the coming catastrophe that would shatter this fragile prosperity.

Landscape of Kinnereth, by Jakob Nussbaum (1873-1936), Frankfurt am Main, 1925, Oil on canvas mounted on hardboard.

Landscape of Kinnereth, by Jakob Nussbaum (1873-1936), Frankfurt am Main, 1925, Oil on canvas mounted on hardboard.

Banks of the Main River, with a View of the Old Bridge, by Jakob Nussbaum (1873-1936), Frankfurt am Main, 1903, Oil on canvas.

Banks of the Main River, with a View of the Old Bridge, by Jakob Nussbaum (1873-1936), Frankfurt am Main, 1903, Oil on canvas.

Chalk drawings by Else Meidner (1901-1987).

Chalk drawings by Else Meidner (1901-1987).

During the Nazi era

With the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933, Frankfurt’s Jewish community faced systematic anti-semitic persecution. Jewish businesses were boycotted, professionals were dismissed from their positions, and discriminatory laws stripped Jews of their rights. Like in other cities such as Cologne, Jews were gradually isolated from public life, prohibited from attending universities, working in the civil service, or even frequenting certain public spaces. The 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom led to the destruction of synagogues, Jewish businesses, and homes, further accelerating the exodus of Jews from the city. Many sought to emigrate, but restrictive immigration policies and financial burdens made escape increasingly difficult.

‘O Drama Judaico’ with a written dedication to the União, an aid association for refugees from nazism, Rabbi Dr. Heinrich Lemle (1909-1978), Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, 1944

‘O Drama Judaico’ with a written dedication to the União, an aid association for refugees from nazism, Rabbi Dr. Heinrich Lemle (1909-1978), Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, 1944

By the early 1940s, deportations to concentration camps had begun. Entire families were rounded up and sent to ghettos and extermination camps in the East. Frankfurt’s once-thriving Jewish community was decimated, with thousands murdered in the Holocaust. Few survived the atrocities, and those who did often returned to find their homes and properties confiscated. The legacy of this destruction remains a painful chapter in the city’s history, remembered through memorials, survivor testimonies, and continued historical research.

‘Siddur’, Norbert Strauss (born 1927) received this prayer book In 1940 from his Hebrew teacher as a gift for his bar mitzvah and took it with him when he emigrated Rodelheim.

‘Siddur’, Norbert Strauss (born 1927) received this prayer book In 1940 from his Hebrew teacher as a gift for his bar mitzvah and took it with him when he emigrated Rodelheim.

Jacket from the Dachau concentration camp (1944/1945), owned by Friedrich Schafranek (1924-2013).

Jacket from the Dachau concentration camp (1944/1945), owned by Friedrich Schafranek (1924-2013).

Gauge I Märklin 5804 Compartment Car 2nd KI. DB. Reminder of the deportation of October 19, 1941 Göppingen, 2nd half of the 20th century, Plastic, metal.

Gauge I Märklin 5804 Compartment Car 2nd KI. DB. Reminder of the deportation of October 19, 1941 Göppingen, 2nd half of the 20th century, Plastic, metal.

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Exhibition ‘Zerstörte Leben’ (‘Destroyed Lives’).

Since 1945

The post-war period saw a slow and complex process of Jewish revival in Frankfurt. Survivors, displaced persons, and returning refugees faced immense challenges, from reclaiming lost property to overcoming the psychological scars of the Holocaust. Despite these hardships, they began rebuilding Jewish institutions, fostering a renewed sense of community and identity. In the early years, Jewish life was marked by uncertainty, as many survivors initially viewed Germany as a temporary place of residence. However, with time, efforts to reestablish Jewish religious, cultural, and educational structures took hold, leading to the gradual revival of Jewish life in the city.

Fritz Bauer (1903-1968) was persecuted by the National Socialists as a Jew and Social Democrat. He returned to the Federal Republic of Germany from exile in Sweden in 1949. He was convinced that a humane society after the end of National Socialism consisted of preserving the dignity of every individual.

Fritz Bauer (1903-1968) was persecuted by the National Socialists as a Jew and Social Democrat. He returned to the Federal Republic of Germany from exile in Sweden in 1949. He was convinced that a humane society after the end of National Socialism consisted of preserving the dignity of every individual.

The establishment of new synagogues, cultural centers, and educational programs helped to reestablish Jewish traditions while adapting to the realities of a new era. Organizations such as the Central Council of Jews in Germany played a crucial role in advocating for the rights and recognition of Jewish communities. Commemorative efforts, including the establishment of memorials and historical research projects, helped to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive while reinforcing the resilience of the Jewish people.

The case of Dr. Herbert Lewin, 1949. Several anti-Semitic incidents after 1945 testify to the fact that attitudes from the Nazi period persisted. This is illustrated by the story of Herbert Lewin. The municipal authorities of the city of Offenbach annulled his election as director of a women’s clinic and justified their decision with racist arguments. The press reports led to the appointment of an investigative commission that confirmed Dr. Lewin as director of the clinic.The episode led to the resignation of Mayor Kasperkowitz of Offenbach.

The case of Dr. Herbert Lewin, 1949. Several anti-Semitic incidents after 1945 testify to the fact that attitudes from the Nazi period persisted. This is illustrated by the story of Herbert Lewin. The municipal authorities of the city of Offenbach annulled his election as director of a women’s clinic and justified their decision with racist arguments. The press reports led to the appointment of an investigative commission that confirmed Dr. Lewin as director of the clinic.The episode led to the resignation of Mayor Kasperkowitz of Offenbach.

Today, Frankfurt hosts one of Germany’s largest Jewish communities, with a vibrant cultural and religious presence. The Jewish Museumꜛ, commemorative projects, and interfaith initiatives serve as reminders of the community’s enduring legacy and resilience. Annual events such as Jewish cultural festivals, lectures, and Holocaust remembrance ceremonies highlight both the historical significance and the continuing contributions of Jewish life in Frankfurt. Despite the challenges of the past, the Jewish community in Frankfurt remains an integral part of the city’s diverse cultural landscape.

Paysage. Le mur rose, by Henri Matisse (1869-1954), France, Corsica, 1898, Oil on canvas. This painting was part of the collection of Frankfurt businessman Harry Fuld (1879-1932). Theft and late restitution: The Nazis systematically plundered Jewish property, particularly works of art. The full return of these artworks to their owners and heirs continues to the present day. After the war, the provenance of many artworks could not be ascertained and they ended up in the collections of large museums. The Washington Declaration of 1998 renewed efforts at financial compensation and restitution. The painting "Paysage. Le mur rose" by Henri Matisse originally belonged to the businessman Harry Fuld, who founded H. Fuld & Co. Telefon und Telegraphenwerke AG in Frankfurt. His son had to leave the painting behind when he emigrated from Germany in 1937. In 1945, this work was discovered in a hiding place in a French military prison. The story of this painting stands for those of many other works of art.

Paysage. Le mur rose, by Henri Matisse (1869-1954), France, Corsica, 1898, Oil on canvas. This painting was part of the collection of Frankfurt businessman Harry Fuld (1879-1932). Theft and late restitution: The Nazis systematically plundered Jewish property, particularly works of art. The full return of these artworks to their owners and heirs continues to the present day. After the war, the provenance of many artworks could not be ascertained and they ended up in the collections of large museums. The Washington Declaration of 1998 renewed efforts at financial compensation and restitution. The painting "Paysage. Le mur rose" by Henri Matisse originally belonged to the businessman Harry Fuld, who founded H. Fuld & Co. Telefon und Telegraphenwerke AG in Frankfurt. His son had to leave the painting behind when he emigrated from Germany in 1937. In 1945, this work was discovered in a hiding place in a French military prison. The story of this painting stands for those of many other works of art.

Conclusion

The history of the Jewish community in Frankfurt reflects both remarkable resilience and the persistent challenges of discrimination and exclusion. While Jewish individuals and families shaped Frankfurt’s economic, cultural, and intellectual identity, their successes often provoked resentment and exclusionary politics. The promises of the Enlightenment and emancipation were never fully realized, as prejudices persisted in both overt and subtle forms. The Holocaust demonstrated the ultimate consequence of such hostilities, leading to the near destruction of a once-thriving community.

Today, Frankfurt’s Jewish community, though significantly smaller than before 1933, has reestablished a presence in the city. However, the scars of the past remain deeply embedded in collective memory. The Jewish Museumꜛ serves as an essential institution, preserving and documenting this complex history while ensuring that the voices of those who suffered are not forgotten. It stands as a reminder that while Jewish life in Frankfurt endures, vigilance against discrimination and historical amnesia remains crucial.

Whenever you find yourself in Frankfurt, I highly recommend visiting the Jewish Museumꜛ. It provides a profound insight into the centuries of Jewish life in the city, offering a nuanced perspective on both historical hardships and cultural achievements. Through its exhibitions, the museum fosters awareness and understanding, making it an essential stop for anyone interested in Frankfurt’s rich and complex past.

References and further reading

- Tobias Freimüller, Frankfurt und die Juden: Neuanfänge und Fremdheitserfahrungen 1945-1990, 2020, Wallstein, ISBN: 978-3835336780

- Sylvia Asmus, Jessica Beebone, Kinderemigration aus Frankfurt am Main: Geschichten der Rettung, des Verlusts und der Erinnerung, 2021, Wallstein, ISBN: 978-3835339842

- Friedrich Lotter, Johann Christian Lotter, Aus dem Dunkel: Wie Juden aus Frankfurt/Oder den Nazis entkamen, 2024, Independently published, ISBN: 979-8303900233

- Amos Elon, Matthias Fienbork (translator), Der erste Rothschild: Biographie eines Frankfurter Juden, 1998, Rowohlt Buchverlag, ISBN: 978-3498016630

- Amos Elon, The pity of it all: A portrait of Jews in Germany 1743–1933, 2004, Penguin, ISBN: 978-0140283945

- Eugen Mayer, Die Frankfurter Juden: Blicke in die Vergangenheit, 1966, Kramer, Waldemar, ISBN: 978-3782903653

- Fritz Backhaus, Gisela Engel, Die Frankfurter Judengasse: Jüdisches Leben in der frühen Neuzei, 2007, Frankfurter Societäts-Druckerei, ISBN: 978-3797309273

- RachelHeuberger, Helga Krohn, Hinaus aus dem Ghetto… Juden in Frankfurt am Main, 1800-1950, 1988, S.Fischer, ISBN: 978-3100314079

- Stern, Fritz, The failure of illiberalism: Essays on the political culture of modern Germany, 1992, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231079099

- Helga Krohn, “Es war richtig, wieder anzufangen”: Juden in Frankfurt am Main seit 1945, 2011, Brandes & Apsel, ISBN: 978-3860996911

- Historisches Museum, Frankfurts demokratische Moderne und Leopold Sonnemann - Jude, Verleger, Politiker, Mäzen, 2009, Frankfurter Societäts-Druckerei, ISBN: 978-3797311504

- Wesbite of the Jewish Museum in Frankfurtꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Philo-Verlagꜛ

comments