Parallelomania and parallelophobia: The cautionary challenges of comparative analysis

The human mind has a natural inclination to identify patterns and connections, even across seemingly disparate domains. This cognitive tendency has driven significant intellectual achievements, from the discovery of universal scientific principles to the comparative analysis of religions, myths, and cultures. However, this same propensity can lead to what is called “parallelomania”, the uncritical identification of parallels that lack substantive grounding, as well as its counterpart, “parallelophobia”, an excessive aversion to drawing connections for fear of oversimplification or error.

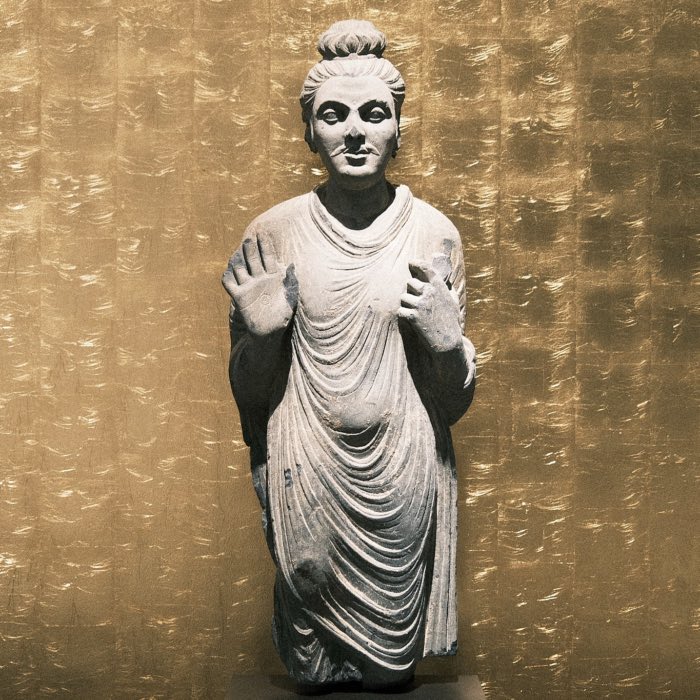

Early depictions of Christ and Buddha, from L’art Greco Bouddhique Du Gandhara by Foucherꜛ, 1905. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Both phenomena pose challenges for scholarly inquiry, particularly in fields such as comparative religion, literary studies, and anthropology, where discerning genuine relationships from superficial or coincidental similarities is a delicate task. In this post, we explore the cautionary challenges of parallelomania and parallelophobia, highlighting the risks of overzealous comparisons and the dangers of excessive aversion to connections. We also check how to navigate the middle ground by applying methodological rigor and contextual analysis to comparative inquiry.

Parallelomania: The pitfalls of overzealous comparisons

The term “parallelomania” was coined by Samuel Sandmel in 1961 to describe a methodological tendency among scholars to identify parallels between texts or traditions without sufficient evidence or critical scrutiny. While Sandmel applied the term primarily to biblical studies, its implications extend far beyond this domain.

Parallelomania often arises from a desire to establish connections that lend weight to a particular argument or theory. For instance, scholars may seek to demonstrate the influence of one tradition upon another by highlighting shared motifs, symbols, or narratives. While such comparisons can be illuminating when grounded in evidence, they risk devolving into speculation when the connections are tenuous or forced.

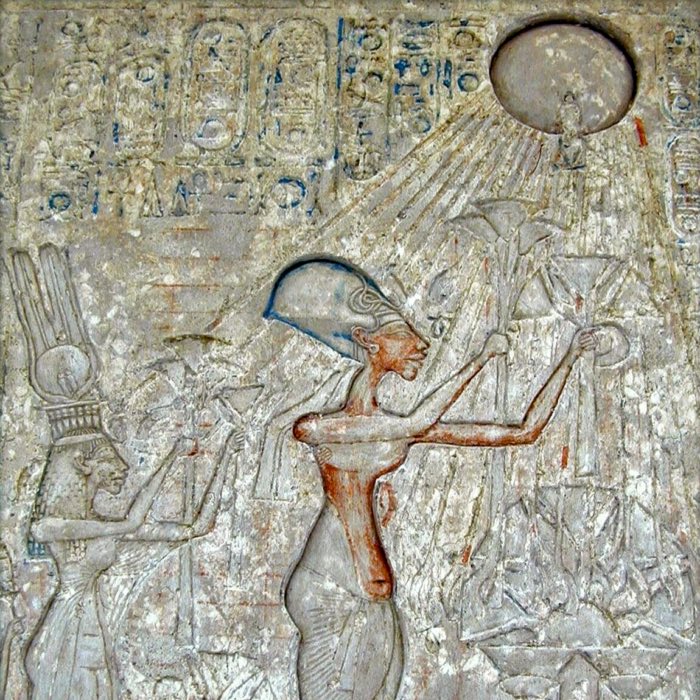

One classic example of parallelomania is the comparison of Jesus and Horus in attempts to argue for a direct borrowing of Christian motifs from Egyptian mythology. Proponents of this parallel often cite alleged similarities, such as miraculous births and resurrection themes. However, many of these claims rely on distorted or selective readings of the source material, ignoring the distinct cultural and theological contexts in which these narratives emerged.

The risks of parallelomania

Parallelomania undermines scholarly credibility and can distort our understanding of historical and cultural phenomena. By privileging superficial similarities over deeper contextual analysis, it risks erasing the unique characteristics of the entities being compared. Moreover, it can perpetuate misconceptions, as exaggerated or false parallels often gain traction in popular discourse.

Parallelophobia: The excessive aversion to connections

At the opposite extreme lies “parallelophobia”, a reluctance to acknowledge genuine connections or influences for fear of oversimplifying or compromising the integrity of the entities involved. This caution often arises as a reaction to the excesses of parallelomania but can be equally problematic.

Paralysis in comparative inquiry

Parallelophobia can lead to a form of intellectual paralysis, where scholars hesitate to draw even well-supported comparisons for fear of being accused of reductionism or ethnocentrism. This aversion can stifle interdisciplinary collaboration and limit our ability to identify shared human experiences and cross-cultural exchanges.

Case studies of parallelophobia

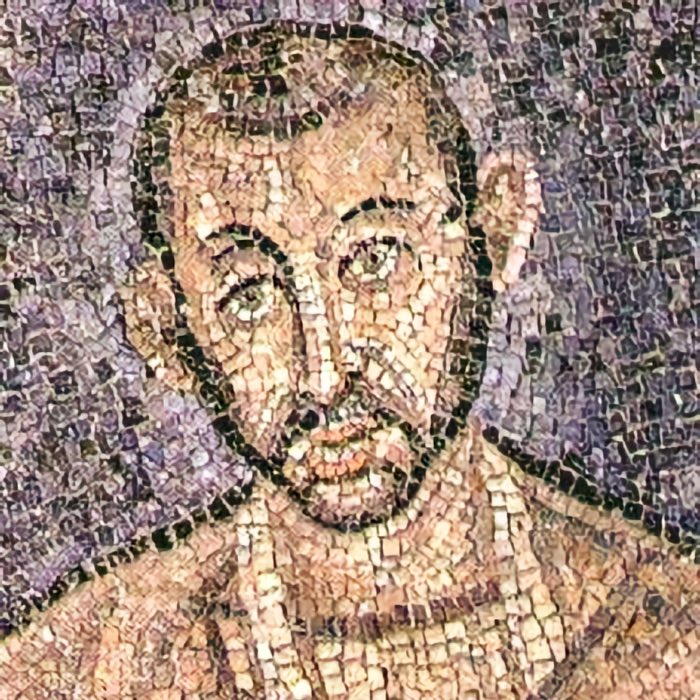

In the study of world religions, parallelophobia might manifest as a refusal to acknowledge the influence of Hellenistic philosophy on early Christian theology, despite substantial historical and textual evidence. Similarly, in literary studies, a rigid insistence on the uniqueness of a particular work can obscure the ways in which authors borrow and adapt ideas from their predecessors.

Navigating the middle ground: Methodological caution and rigor

Avoiding the twin pitfalls of parallelomania and parallelophobia requires a balanced approach that combines openness to connections with rigorous methodological scrutiny. Comparative analysis must be grounded in careful examination of evidence, attention to historical and cultural contexts, and a commitment to avoiding both overgeneralization and undue compartmentalization.

Establishing criteria for parallels*

Scholars should establish clear criteria for identifying meaningful parallels, focusing on factors such as historical plausibility, textual or material evidence, and the broader cultural frameworks in which the entities under comparison operated. Genuine parallels often involve shared influences or direct interactions, rather than coincidental similarities.

Contextualizing similarities

Contextualization is key to avoiding the pitfalls of parallelomania. For example, while resurrection themes appear in multiple religious traditions, their meanings and functions vary widely. A careful analysis of these differences can enrich our understanding of the specific cultural and theological concerns that shaped each tradition.

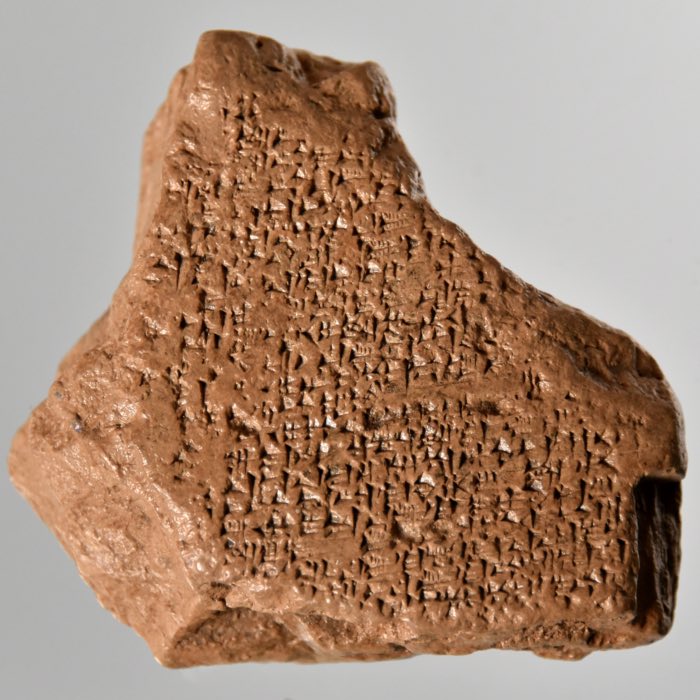

The value of genuine connections

When conducted responsibly, comparative analysis can reveal profound insights into the shared human experience. For instance, examining the similarities and differences between the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Homeric epics illuminates the ways in which ancient cultures grappled with themes of heroism, mortality, and the search for meaning. Such comparisons enhance our understanding of ancient worldviews and the relevance of these texts.

Examples

Some prominent examples of parallelomania and parallelophobia in scholarly discourse include:

- The claimed link between the Egyptian god Aten and YHWH, where Aten is seen as a precursor to the monotheistic conception of YHWH/God in Judaism.

- The claimed link between Pyrrhonism and [Buddhist](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-05-16-buddhism/) philosophy of Nagarjuna, where scholars debate the extent of direct influence versus convergent evolution.

- Richard Carrier’s theory of Jesus being invented out of the mixture of Jewish and Greco-Roman myths as a mystery cult figure.

- The claims that Jesus was a Buddhist monk or that he visited India, which are often dismissed as parallelomania due to lack of historical evidence.

Ethical dimension

Both parallelomania and parallelophobia have ethical implications, particularly when used to advance ideological or political agendas. Overzealous parallels can be weaponized to assert cultural superiority, fabricate historical narratives, or promote unfounded theories that serve particular interests. In contrast, a refusal to acknowledge connections can reinforce divisive narratives, uphold exclusivist claims, and hinder a comprehensive understanding of cultural and intellectual exchanges. Scholars, educators and anyone engaging in comparative analysis bear a responsibility to approach comparisons with humility, rigor, and a commitment to fostering mutual understanding, ensuring that analysis is driven by evidence rather than by preconceived biases or ideological motives.

Conclusion

Parallelomania and parallelophobia mark two extremes in comparative analysis, each presenting its own risks and challenges. While uncritical parallels can lead to historical distortions and misrepresentations, an overly cautious approach may obscure genuine patterns and intellectual exchanges. Striking a balance requires methodological rigor, a nuanced appreciation of complexity, and a commitment to preserving both the distinctiveness and interconnectivity of human traditions. By carefully weighing evidence and context, scholars and layperson alike can navigate these tensions and foster a more informed and meaningful discourse on cultural and historical relationships.

References and further reading

- Sandmel, S., Parallelomania, 1962, Journal of Biblical Literature. 81 (1): 1–13. doi: 10.2307/3264821ꜛ, JSTOR 3264821

- Wikipedia article on Parallelomaniaꜛ

comments