Christianity vs. Eastern traditions: Divergent paths to the Absolute

After examining the nature and institutional framework of Christianity in our previous post, we now turn to a broader comparison between Christianity and Eastern traditions. The distinction between the two traditions lies at the heart of some of the most profound philosophical, theological, and cultural differences in human thought. While Christianity, emerging as a synthesis of Jewish traditions and Greco-Roman philosophy, centers on the worship of an absolute, omniscient deity, Eastern traditions such as Daoism and Buddhism often emphasize a spiritual philosophy. These traditions blur the lines between religion and philosophy, offering a path for individual enlightenment and harmony with the cosmos. By examining the foundational tenets of these traditions, we can better understand how they represent two fundamentally distinct approaches to the pursuit of the Absolute.

Sculpture of Zen master Taisen Deshimaru in the Zen garden of Kosan Ryumon-ji in Weiterswiller, France. Deshimaru was a Japanese Sōtō Zen Buddhist teacher who introduced Sōtō Zen Buddhism to Europe in the 1960s. Through his writings and teachings, he made Zen practice accessible to a wide European audience. He founded the Association Zen Internationale and established the first Zen temple in Europe, La Gendronnière, in France. Today, many European Zen centers are affiliated with his teachings. Unlike Christian traditions, Zen Buddhism emphasizes direct experience and personal realization of the Absolute. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Christianity: Fusion of Jewish tradition and Greco-Roman philosophy

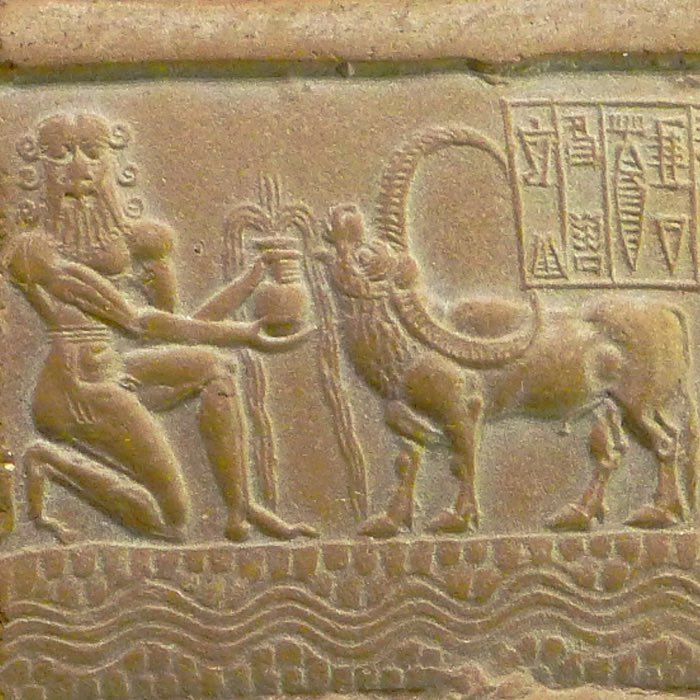

Mesopotamian foundations

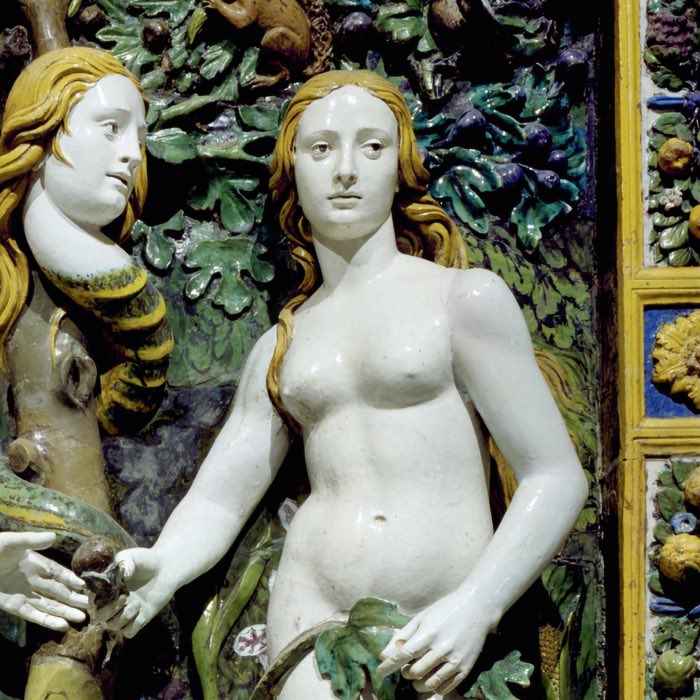

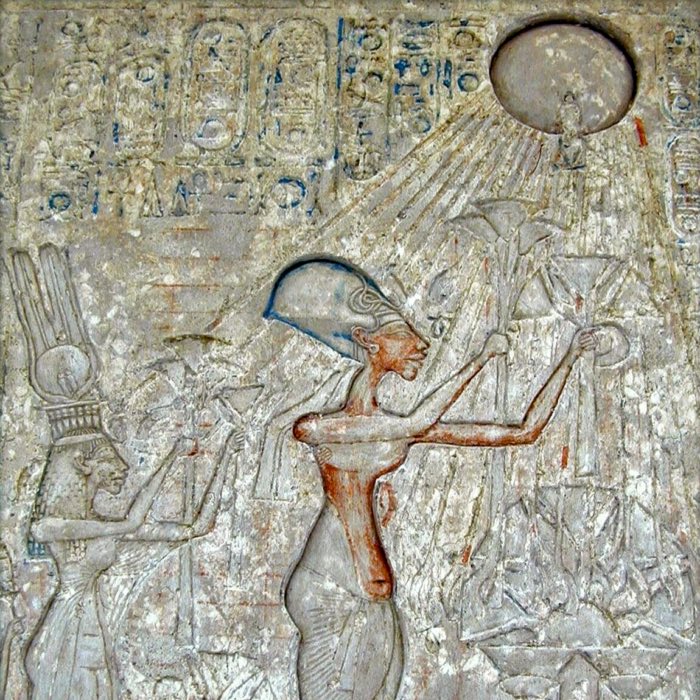

The origins of Christianity can be traced back through Judaism, which itself was influenced by ancient Mesopotamian civilizations, where belief in powerful celestial beings governed the understanding of life and the cosmos. Mesopotamian religions were polytheistic, with gods such as Anu, Enlil, and Ishtar wielding control over the elements, human destiny, and the natural world. These gods were anthropomorphic, embodying human virtues and vices while existing in a realm distinctly separate from humanity. The relationship between humans and the divine was transactional, maintained through rituals, sacrifices, and strict adherence to divine laws.

This framework laid the groundwork for later developments in Judaism, which shifted the polytheistic paradigm toward monotheism. The Hebrew Bible presents a single, omnipotent deity who is both creator and moral lawgiver. Yahweh’s authority is absolute, requiring obedience from his followers under a covenantal relationship. This conception of a transcendent deity became central to the Jewish tradition and, subsequently, Christianity.

Christianity: A Greco-Roman mystery cult with Jewish foundations

Christianity did not emerge solely from Jewish traditions but rather as a distinct stream within Judaism that evolved into a Greco-Roman mystery cult centered around the figure of Jesus Christ. It appropriated Jewish foundational elements but was heavily shaped by Hellenistic thought and the structural and theological frameworks of existing mystery religions in the Greco-Roman world. This synthesis allowed Christianity to transition from a Jewish sect into a broader, more adaptable religion, incorporating elements of divine incarnation, sacrificial redemption, and mystical rites common in contemporary mystery cults. Central to Christianity is the belief in the Incarnation — that God took human form in Jesus, bridging the divine and human realms. This idea reinforces Christianity’s focus on divine authority and its intervention in the human condition.

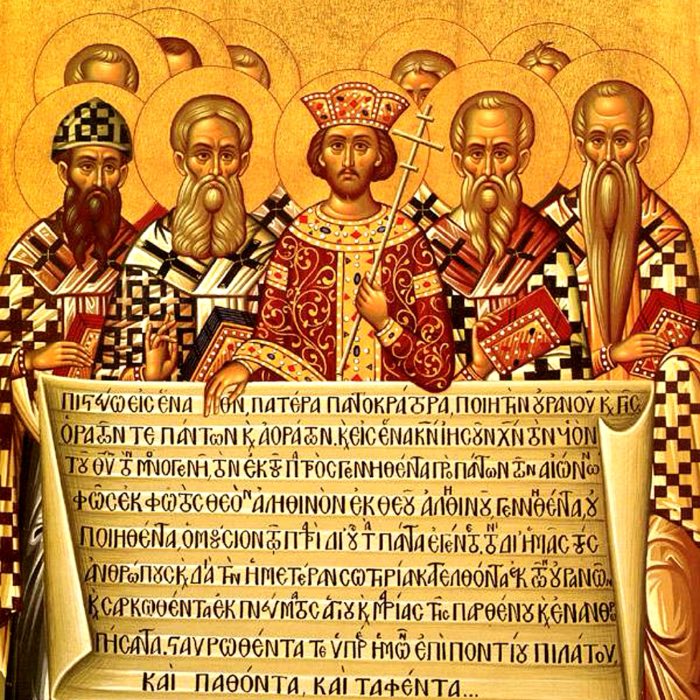

The institutionalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire was crucial in shaping its identity as a Greco-Romanized mystery religion. As it assimilated Neoplatonic and Stoic philosophical elements, Christianity was systematically transformed from a diverse movement into a codified theological system, ensuring hierarchical control and dogmatic rigidity. This transformation ensured that Christianity was no longer simply a continuation of Jewish traditions but a new religious framework that drew heavily from Greco-Roman philosophical and religious influences. The establishment of creeds, such as the Nicene Creed, and the hierarchical structure of the Church were deliberate mechanisms to solidify theological control, ensuring a rigid distinction between orthodoxy and heresy. The emphasis on absolute truths and a single path to salvation reflects the broader Christian tendency to prioritize divine authority and universal moral imperatives.

Eastern traditions: Spiritual philosophy and the cosmic order

Daoism: Harmony with the Dao

In contrast to Christianity’s focus on a supreme deity, Daoism in China offers a spiritual philosophy centered on aligning oneself with the Dao, an ineffable force that underlies and sustains the universe. The Dao is not a god but a principle that governs natural order, spontaneity, and balance. The Daoist text Dao De Jing, attributed to Laozi, emphasizes concepts such as wu wei (non-action or effortless action), which encourages individuals to live in harmony with the natural flow of life rather than imposing control.

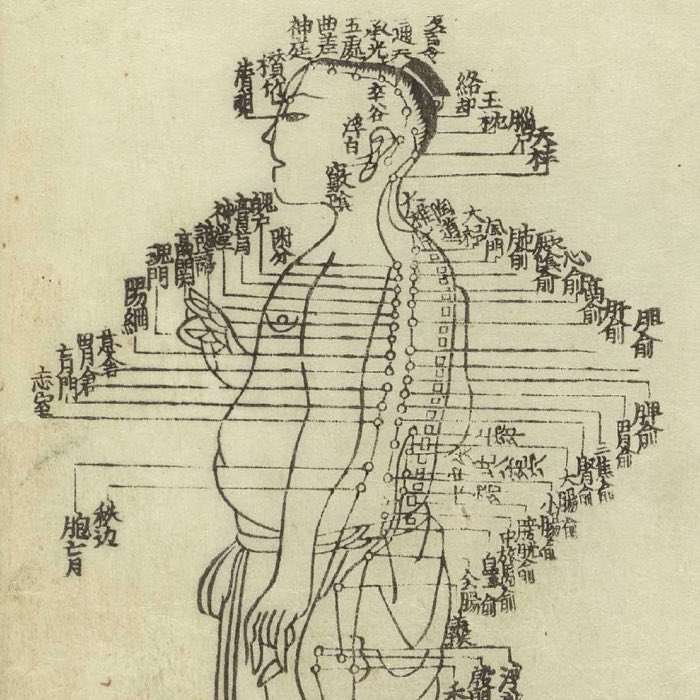

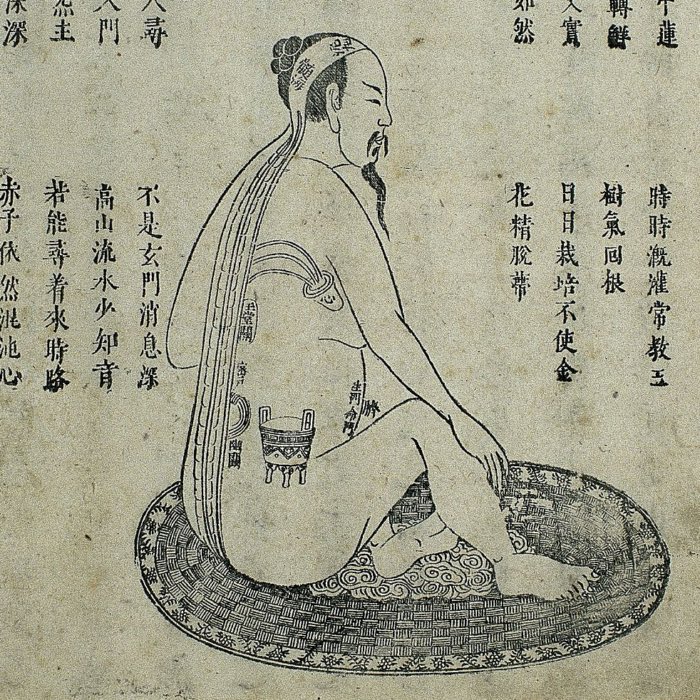

Daoism blurs the lines between religion and philosophy. Rituals and practices, such as meditation, tai chi, and alchemy, aim to harmonize the body, mind, and spirit with the Dao. Unlike Christianity, Daoism does not present a definitive moral code or an absolute deity. Instead, it offers a flexible framework for achieving balance and tranquility, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all existence.

Buddhism: The path to liberation

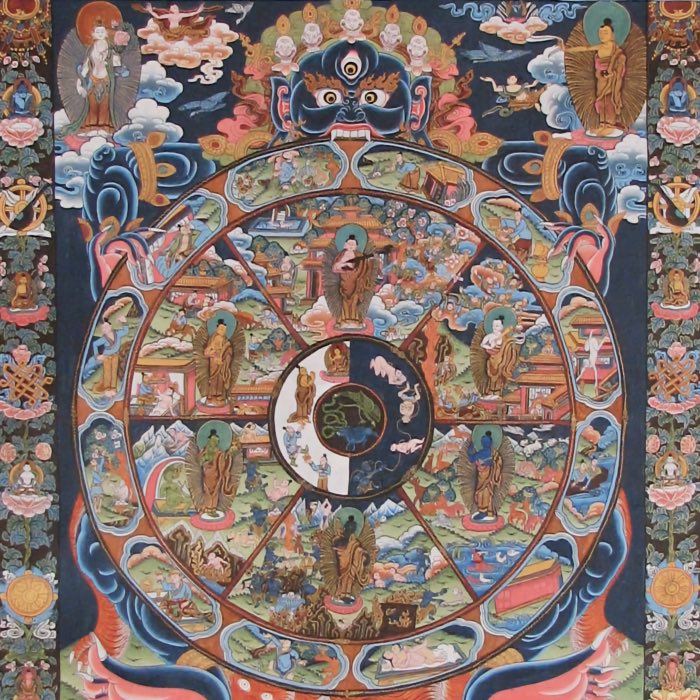

Buddhism, originating in India and spreading to China, Korea, and Japan, exemplifies another Eastern approach that diverges from Christianity’s absolutes. Founded by Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, Buddhism centers on the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, which outline a practical guide for overcoming suffering (dukkha) and achieving enlightenment (nirvana).

Rather than appealing to a creator deity, Buddhism focuses on the individual’s journey toward liberation through ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom. The Buddhist concept of impermanence (anicca) and the absence of a permanent self (anatta) challenge the notion of an eternal soul, a concept prevalent in Christianity. Practices such as meditation and mindfulness are aimed at transcending the cycles of desire and attachment, fostering spiritual growth.

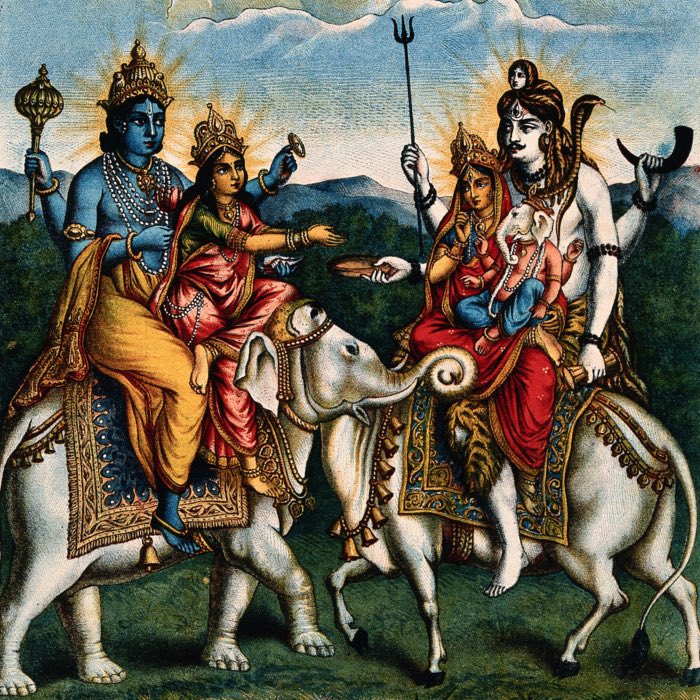

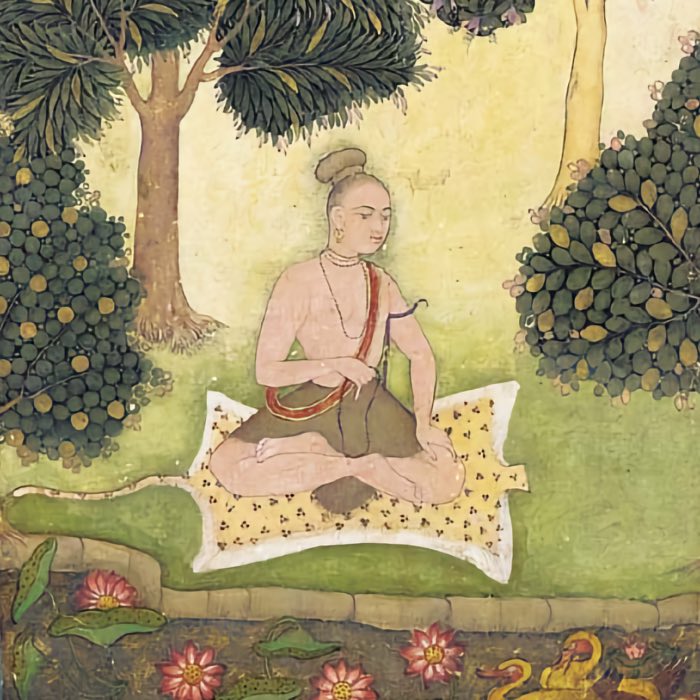

Hinduism: The roots of Eastern spirituality

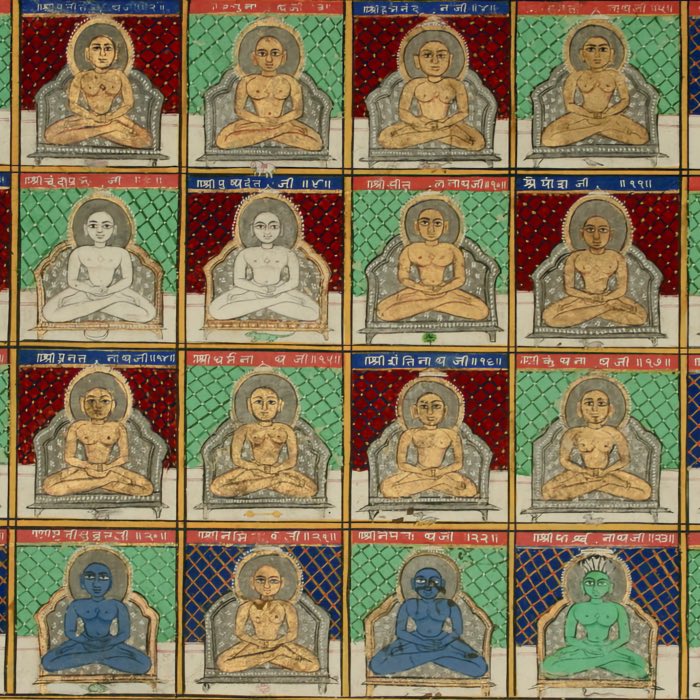

Hinduism, one of the world’s oldest religious traditions originating in India, provides a rich set of beliefs that influenced other major Eastern traditions such as Buddhism and Jainism. Rooted in the Vedas, Hinduism encompasses a vast array of deities, practices, and philosophical systems. Unlike Christianity’s monotheism, Hinduism embraces polytheism while maintaining a profound metaphysical unity in the concept of Brahman—the ultimate reality.

The Hindu emphasis on dharma (duty) and karma (action and its consequences) reflects a cyclical worldview, contrasting sharply with the linear eschatology of Christianity. The Upanishads, philosophical texts within the Hindu canon, explore profound questions about the self (atman), the universe, and the divine, offering insights that resonate with both religious devotion and philosophical inquiry.

Christianity and Eastern traditions: Defining and approaching the Absolute

Despite their theological and philosophical differences, both Christianity and Eastern traditions engage with the idea of an ultimate reality, but their approaches diverge fundamentally. While Eastern traditions encourage direct, personal exploration of the Absolute, Christianity, through its institutional structures, historically confined spiritual pursuit within rigid theological boundaries. The metaphysical connection between these traditions exists in their shared concern with the Absolute, yet Christianity’s hierarchical framework often obstructed individual engagement, enforcing prescribed belief over exploratory experience.

The Absolute in Christianity: Personification and revelation

In Christianity, the Absolute is not freely explored but personified as a deity whose nature and will are dictated by institutional doctrines, reinforcing hierarchical authority and control over spiritual engagement. This personification makes the invisible visible, providing a tangible focal point for worship and devotion. In Christianity, for example, the concept of God as Father, Creator, and Redeemer allows believers to relate to the divine on a personal level. The Incarnation, in which God becomes human in the person of Jesus Christ, exemplifies this effort to bridge the transcendent and the immanent.

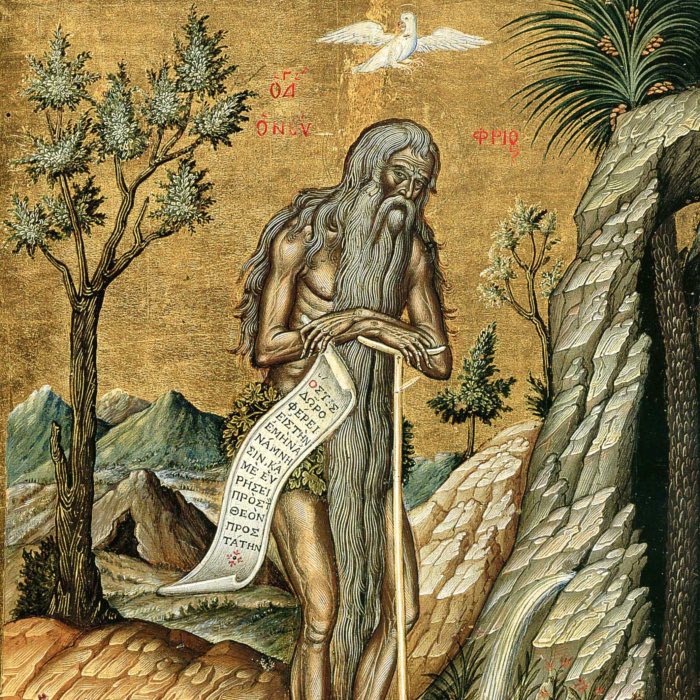

While this approach emphasizes divine revelation — the idea that the Absolute reveals itself to humanity through scripture, prophets and saints, bones and other relics, icons, and sacred events — mystical traditions within Christianity often found themselves at odds with institutional authority. Figures such as Meister Eckhart and St. John of the Cross attempted to reclaim a more direct experience of the Absolute but frequently faced suppression from the Church, illustrating how institutional Christianity historically sought to control spiritual experience rather than foster it.

The Absolute in Eastern traditions: Negation and inner realization

Eastern traditions approach the Absolute not as a personal deity but as an ineffable principle that transcends all categories of thought and language. In Daoism, the Dao is described as nameless and beyond definition: “The Dao that can be spoken is not the eternal Dao”. Similarly, in Buddhism, the ultimate reality is characterized by sunyata (emptiness), a concept that defies conceptualization and invites direct experiential understanding through meditation and mindfulness.

Hindu philosophy, particularly in the Upanishads, describes Brahman as the unchanging, infinite reality that underlies all existence. Like the Dao or sunyata, Brahman is beyond human grasp but can be approached through practices such as meditation, devotion, and self-inquiry (jnana yoga). These paths emphasize inner transformation and direct experience rather than external revelation.

Parallel paths: Apophatic theology and mysticism

The Eastern emphasis on negation and inner realization finds parallels in Western apophatic theology. Both traditions recognize the limitations of human language and thought when it comes to describing the Absolute. For example, the Christian tradition of via negativa (“the way of negation”) asserts that God cannot be fully understood through positive attributes but can be approached by stripping away all inadequate concepts.

Moreover, mystical practices in both traditions aim to transcend the ego and connect with the Absolute on a direct, experiential level. Whether through Christian contemplative prayer, Buddhist meditation, or Daoist practices of harmony with the Dao, these approaches reveal a shared human aspiration to unite with the ultimate reality.

Reconciling the transcendent and the immanent

While Christianity and Eastern traditions diverge in their articulation of the Absolute, both grapple with the tension between its transcendence and immanence. Christianity often resolves this tension through the concept of divine incarnation, as in the Christian belief in Jesus Christ. Eastern traditions, on the other hand, emphasize the immanence of the Absolute within the natural world and the individual self, inviting practitioners to discover the divine within themselves.

While both Christianity and Eastern traditions engage with questions of the Absolute, Christianity’s institutionalized structure has largely restrained direct experiential spirituality, in contrast to the open-ended exploration characteristic of Eastern traditions. This divergence highlights how Christianity, rather than facilitating a metaphysical pursuit, has historically functioned as a regulatory system that channels and restricts access to the divine. Both seek to understand the ultimate nature of existence and provide pathways for individuals to connect with it, offering profound insights into the human experience.

Comparative summary: Christianity vs. Eastern traditions

The following table summarizes the key differences between Christianity and Eastern traditions in their approach to the divine, ethics, relationship with the Absolute, cosmology, and mysticism:

| Aspect | Christianity | Eastern traditions | Common ground |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of the Divine | Personal, transcendent deity whose authority is enforced through institutionalized doctrine | Impersonal, ineffable principle beyond language (e.g., Dao, Brahman, or sunyata) | Acknowledgment of an ultimate, transcendent reality |

| Ethics | Divine moral absolutes and commandments dictated by scripture and institutional authority | Contextual, fluid ethics emphasizing harmony and balance | Emphasis on human responsibility and moral action |

| Relationship with the Absolute | Mediated through scripture, church hierarchy, rituals, veneration of dead body parts and other objects, and belief in divine revelation | Inner transformation to realize unity with the Absolute through direct experience | Use of spiritual practices to approach the transcendent |

| Cosmology | Linear eschatology with a definitive beginning and end, guided by divine intervention | Cyclical view of existence (e.g., samsara, reincarnation), with liberation from suffering as the goal (moksa, nirvana) | Exploration of humanity’s place within the cosmos |

| Mysticism | Suppressed or regulated within institutionalized Christianity, with mystics often clashing with Church authority | Meditation and direct experience of ultimate reality widely embraced | Pathways to transcendence and union with the Absolute |

Conclusion

The divergence between Christianity and Eastern traditions reflects fundamental differences in how human cultures have sought to understand existence, morality, and the divine. Christianity, though rooted in Jewish traditions, was deliberately redefined through the lens of Greco-Roman philosophy and mystery cults. This synthesis led to the establishment of absolute truths, divine authority, and a linear view of history, framed within the broader theological systems of the Roman world.

In contrast, Eastern traditions, exemplified by Hinduism, Daoism and Buddhism, offer a more fluid, philosophical approach that prioritizes harmony, self-realization, and the cyclical nature of life. While Christianity solidified itself through institutional control and dogmatic rigidity, Eastern traditions remained open-ended, encouraging direct personal engagement with the Absolute rather than submission to theological authority. This fundamental difference in approach has not only shaped the philosophical and theological landscapes of these traditions but has also determined how individuals engage with the Absolute — either through institutionalized doctrine and mediated faith or through direct, personal exploration.

References and further reading

Please refer to the reference lists in all my previous posts since the beginning of this year (or follow the articles listed below in the linked articles sections), as this post serves more or less as a summary of those previous posts.

comments