Is Christianity a true religion?

Christianity has long been regarded as one of the world’s dominant religions, shaping cultures, laws, and individual belief systems for centuries. Yet, beneath its theological claims and institutional authority lies a deeper question — what exactly is Christianity? Is it a genuine religion in the truest sense, or does it serve a different function altogether?

Left: One of the earliest depictions of Jesus: Here as the good. Early Christian ceiling painting in the Calixtus Catacomb in Rome, around 250. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: Portrait of Pope Pius VII and Cardinal Caprara, Jacques-Louis David, ca. 1805. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

I initially approached this question with the assumption that Christianity could be separated into two distinct components: an original, authentic religious core and the later institutions that manipulated and distorted it. However, through my research, which I presented in my previous series of posts, I found that no such subdivision exists. Christianity, from its inception, has functioned as an institutionalized system designed to wield power and maintain authority rather than as a vehicle for genuine spiritual exploration.

In this concluding post, we eventually seek to answer the question: Is Christianity a true religion? To do so, we must first establish a definition of religion that transcends etymology and addresses the fundamental nature of spiritual pursuit. From there, we will examine how Christianity aligns — or fails to align — with this definition, shedding light on its true nature and function in Western society.

Introduction

Before I began my series exploring the history of Christianity, I initially assumed a dichotomy between an “authentic,” that is, original Christianity, and the institutions that later emerged, transforming it into something distinct. However, the more I researched, the more I realized that this dichotomy does not exist at all.

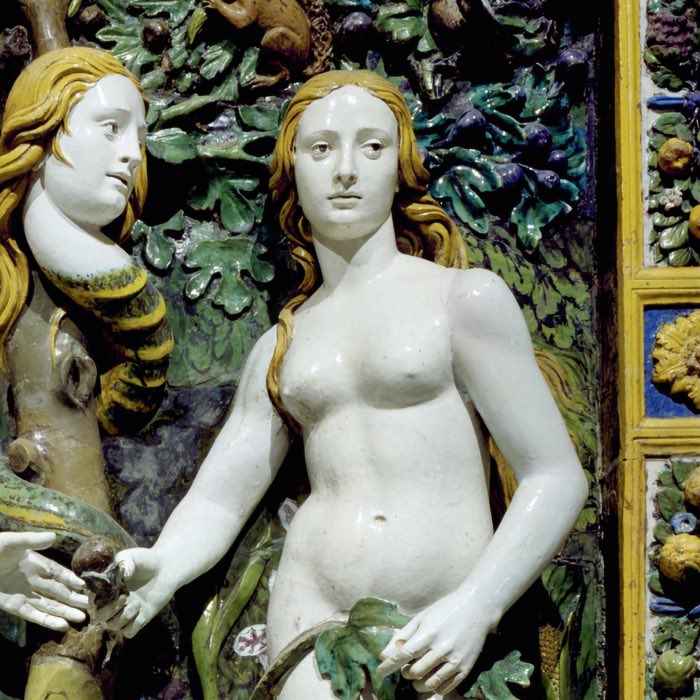

When examining the origins of Christianity, one must conclude that this supposed division never existed. Christianity is the very history of its institutions — a story of power consolidation that we have explored in previous discussions. Christianity is not something separate from the clergy and their actions; rather, it is precisely what these early and later leaders created, shaping it into an inflated mystery cult infused with Greco-Roman philosophy. Today, it continues to be managed and preserved through dogma. Christianity, in fact, does not function without “ecclesiastical leadership,” no matter how one attempts to frame it. Why? Because “Christianity” was designed by and for the Church. Its entire theological structure serves the purpose of legitimizing ecclesiastical authority in every respect. Anyone who claims that the Church has deviated from its own teachings is mistaken — those very teachings were and remain the Church’s instruments of power and control. This is an inseparable reality, a truth that emerges unmistakably from historical analysis.

It is possible that, in its earliest form, Christian teachings had genuine spiritual intentions, providing a path for believers to engage with the Divine/Absolute and with ethics. However, since those early, perhaps innocent beginnings, these teachings have been instrumentalized solely for power legitimization and execution. The doctrine became nothing more than a tool of control and justification for authority.

So, is Christianity truly a religion? Is it a faith held together and controlled by a central institution, the Church? Or is the Church merely a secular organization that exploits religion as a means of legitimization? To answer this question, we must first establish a definition of religion.

What is the truest definition of religion?

The Latin word religio has its roots in the verb religare, meaning “to bind” or “to reconnect”. This etymology suggests that religion, in its essence, is about a bond — between humanity and the Absolute, the Divine, or the ultimate reality. However, defining religion in its truest form requires moving beyond etymology into a more fundamental understanding.

Religion can be broadly understood as the pursuit of exploring and experiencing the Absolute. It encapsulates the human drive to engage with the fundamental nature of existence, whether conceptualized as God, the Absolute, Truth, or Being itself. This pursuit is not limited to any institutionalized form but is rather an existential endeavor — one that seeks to bridge the gap between human consciousness and the ultimate reality it strives to comprehend.

By framing religion in this way, it becomes a universal concept that includes both individual and communal attempts to approach the Absolute. The essence of religion lies not in rigid doctrines or institutions but in the direct engagement with the deepest realities of existence. It is about understanding, experiencing, and transforming in relation to this ultimate reality. Some traditions emphasize intellectual contemplation, while others stress mystical experience or ethical practice, but all share this foundational pursuit.

Thus, in its purest sense, religion is neither a static belief system nor a hierarchical institution. It is the active and dynamic endeavor to connect with the Absolute, the eternal search for meaning and transcendence that defines the human experience.

Is Christianity a true religion?

Christianity, at least in its institutionalized and dogmatic form, often presents itself less as a path to explore the Absolute and more as a predefined system of absolute truth that must be accepted rather than actively pursued. This contrasts with traditions that emphasize direct personal experience, such as certain schools of Buddhism, mystical branches of various religions, or even philosophical approaches to the Absolute.

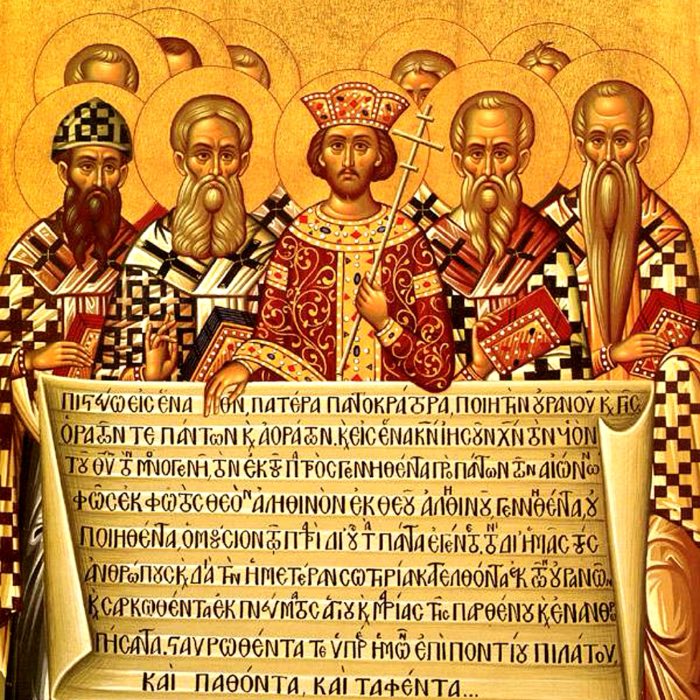

Instead of fostering an open-ended journey toward understanding and experiencing the divine, Christianity established itself as the sole possessor of revealed truth, mediated through scripture, creeds, and church authority. This structural framework enforces an approach in which truth is not discovered by individual seekers but dictated by institutional authority, leaving little room for independent exploration.

The role of the believer is often reduced to passive acceptance of this truth rather than an active seeker engaging with the Absolute in a personal and dynamic way. Faith, within this framework, becomes a matter of adherence to established doctrines rather than a lived and evolving experience of the divine.

Experiences of the divine are not explored freely but must conform to the approved theological framework, limiting individual spiritual discovery. This results in a religious structure that prioritizes obedience over inquiry, hierarchy over personal revelation, and dogma over fluid exploration of the divine.

This institutionalization arguably stifles what could have been an organic, exploratory approach to the divine. The mystics of Christianity — Meister Eckhart, Origen, or the Hesychasts — tried to reclaim a more direct experience of the Absolute, but they often clashed with the Church’s authority because their approaches encouraged independent spiritual activity rather than passive faith – which could have been a threat to the Church’s power.

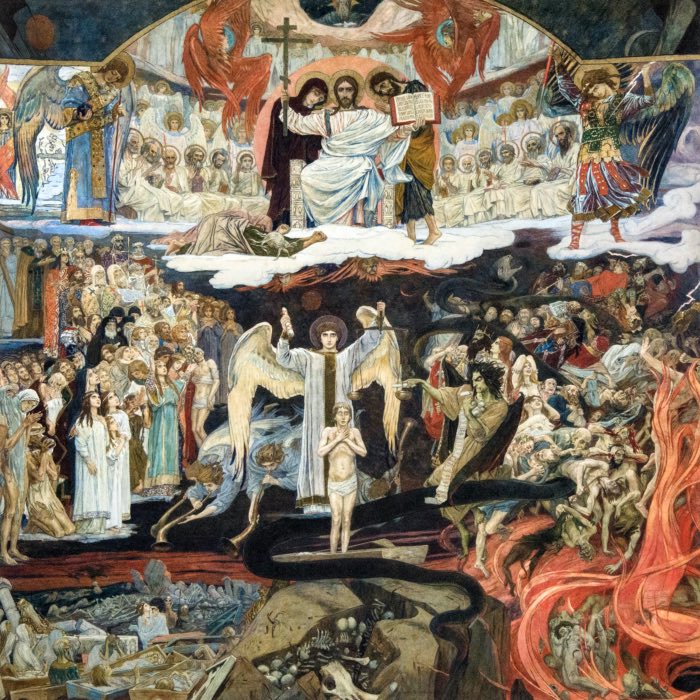

Thus, Christianity as an institution does not align with the truest definition of religion as the active and dynamic pursuit of the Absolute. Instead, it functions as a system of dogmatic control, ensuring that engagement with the divine remains within tightly regulated boundaries. If true religion is about direct experience and exploration, then Christianity, as a structured system of authority and imposed belief, operates more as an ideological framework than a genuine religious pursuit.

So what is Christianity?

If Christianity does not align with the our definition of religion, then what is it? Rather than being a genuine religious pursuit, I think, Christianity can be more accurately described as an ideological system intertwined with institutional power. Its primary function has been to provide a framework for authority, shaping social structures, politics, and cultural norms through its doctrines and institutions. Of course, there is an underlying belief system that the faithful Christians believe in. But this believe system is instrumental in the hands of Christian and secular institutions, leaders and anyone who wants to use it to legitimize power and actions.

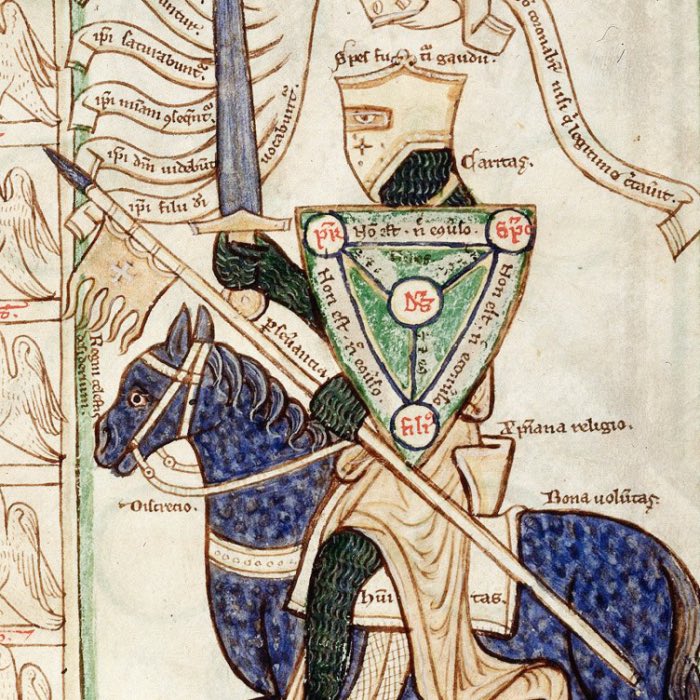

Overall, Christianity has served as a mechanism for organizing society under a unified worldview, one that dictates not just spiritual matters but also moral, legal, and even economic systems. Unlike a religion that encourages exploration of the Absolute, Christianity has functioned more as a theocratic system — an apparatus that enforces a specific worldview while legitimizing its own institutional control.

The alibi function

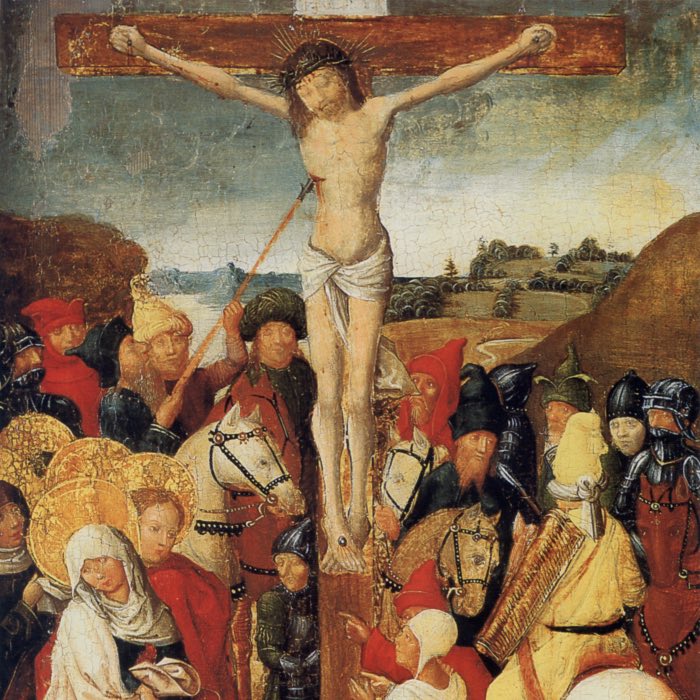

Christianity presents itself as a religion of love, yet its history is one of violence, deception, and exploitation. Time and again, atrocities have been justified under the guise of faith, rebranded as acts of divine will and moral righteousness. The mechanism by which Christianity achieves this is through an intricate self-reinforcing system that allows its adherents to absolve themselves of guilt, regardless of their actions.

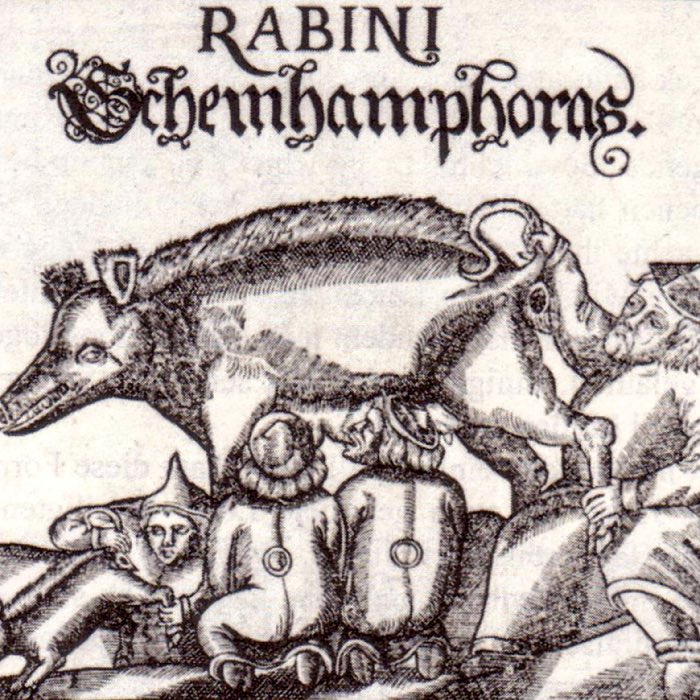

Believers, to soothe their own consciences, redefine their deeds as virtuous — even when they involve conquest, genocide, and abuse — by attributing them to the fulfillment of a divine plan. In the name of spreading love and salvation, entire civilizations have been wiped out, and oppressive structures have been perpetuated for centuries. This self-justification is not a historical accident but an inherent function of the Christian faith, providing a perpetual alibi for moral transgressions.

This dynamic allows Christianity to serve not only as a tool for institutional power but also as a deeply personal psychological mechanism that shields individuals from confronting the ethical implications of their actions. By framing all conduct within the scope of divine intent, Christianity creates a moral loophole — one that permits even the most egregious crimes to be reframed as acts of faith. This is not merely an unfortunate consequence of religious belief but a defining characteristic of Christianity’s structure, ensuring that its adherents can simultaneously engage in acts of oppression while maintaining the conviction that they are instruments of divine love and justice.

Conclusion

Christianity, as we have explored, functions not as a true religion in the purest sense but rather as an ideological structure designed for institutional power and control. Unlike spiritual traditions that encourage individual exploration of the Absolute, Christianity has historically imposed a rigid framework that prioritizes obedience over inquiry, doctrine over experience, and authority over personal revelation.

The institutionalization of Christianity has ensured that its function remains inseparable from its mechanisms of power. By presenting itself as the sole possessor of divine truth, it has wielded control over its adherents, dictating belief and behavior under the guise of moral and spiritual guidance. This has not only preserved its authority but has also provided a systemic alibi for its historical transgressions — legitimizing conquest, oppression, and even atrocity as divine will.

Ultimately, if we define religion as the pursuit of the Absolute through personal and communal engagement, then Christianity fails to meet this standard. It does not offer an open-ended exploration of the divine but enforces a structured belief system that functions more like a theocratic ideology than a true spiritual path. What Christianity has built is not a religion of personal enlightenment but an apparatus for sustaining ecclesiastical authority.

Recognizing this distinction forces us to rethink the role of Christianity in history and in modern society. Is it truly a faith that seeks to connect humanity with the divine, or is it a socio-political construct that has successfully perpetuated its own dominion through theological justification? If spirituality is about seeking truth and transcendence, then perhaps the true religious path lies outside of Christianity’s institutionalized dogma, in the unrestricted exploration of the Absolute beyond the confines of prescribed belief. However, this is a decision that each individual must make for themselves, guided by their own understanding of what constitutes a genuine religious pursuit and guided by their own moral compass.

References and further reading

Apart from Karlheinz Deschner, Horst Herrmann, Der Anti-Katechismus - 200 Gründe gegen die Kirchen und für die Welt, 1993, Goldmann, ISBN: 9783442123438’s monumental work Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums (The Criminal History of Christianity; 1986–2013), which consists of multiple volumes critically investigating the dark history of Christianity, please refer to the reference lists in all my previous posts since the beginning of this year, where I have presented a comprehensive overview of the history of Christianity, its core values, its spread, its institutionalization, and its impact on society.

comments