The Church’s system of child abuse

The sexual abuse of children by Christian clerics represents one of the most disturbing and enduring scandals in religious history. For centuries, the Church has presented itself as a pillar of morality, yet behind this facade lies a deeply entrenched system of abuse, silence, and institutional protection of perpetrators. The exposure of these crimes in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has shattered public trust, revealing a disturbing pattern of concealment that spans across continents and generations.

Statue of an altar boy in a church. Source: Marc Pascualꜛ on Pixabayꜛ

The scale of the crisis is vast, affecting thousands — if not hundreds of thousands — of victims worldwide. Investigations have revealed that the abuse was not the result of isolated incidents but a systemic failure embedded within the Church’s very structure. More concerning, rather than prioritizing justice for the victims, the Church has historically focused on protecting its own reputation and power. The extensive cover-ups, failure to cooperate with law enforcement, and reassignment of abusive clerics to new locations illustrate the institution’s willingness to sacrifice the well-being of its most vulnerable members for the sake of self-preservation.

In this post, we investigate the widespread sexual abuse of children by Christian clerics, focusing on the Catholic Church as the largest Christian denomination. We examine the global scope of the crisis, the Church’s system of concealment, and the consequences for the victims. By comparing the responses of different countries, such as France and Germany, we highlight the importance of independent investigations and the impact of cultural and legal factors on reporting rates. Finally, we discuss what these deeply integrated abuse system means for the Church’s moral authority and its self-perception.

Sexual abuse of children by Christian clerics

The sexual abuse of children by Christian clerics is one of the most egregious and enduring scandals within the Church. For decades, if not centuries, these abuses have taken place under the veil of religious authority and institutional protection. The full extent of the crisis came to light in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as survivors spoke out, investigative journalism exposed systemic patterns of abuse, and independent commissions uncovered thousands — if not hundreds of thousands — of cases worldwide.

The consequences for the victims of clerical abuse are devastating and lifelong. Physically, victims may suffer from injuries resulting from the assaults, but the psychological damage is often even more severe. Many survivors develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and suicidal tendencies. The betrayal by a trusted religious figure exacerbates the trauma, making recovery particularly difficult. In many cases, victims turn to substance abuse, developing dependencies on drugs or alcohol as a means of coping with their pain. The economic consequences of these psychological scars are profound: many survivors struggle to maintain stable employment, relationships, or mental well-being. Social dysfunction, an inability to form trusting relationships, and economic marginalization are common patterns among survivors, leading to further cycles of hardship and vulnerability.

Widespread of the abuse

Revelations of child sexual abuse by clerics have emerged across the globe, demonstrating that this is not an isolated issue confined to any one country or denomination. The scale of abuse varies depending on the level of investigation and reporting, but estimates suggest alarming numbers:

- France: The CIASE report (2021)ꜛ estimated that at least 330,000 children were abused by clerics and lay members of the Catholic Church between 1950 and 2020.

- Germany: A 2018 report commissioned by the German Catholic Bishops’ Conference documentedꜛ 3,677 cases between 1946 and 2014, though this number is believed to be vastly underestimated. A 2024 study into the Protestant Church found over 9,000 cases.

- United States: The John Jay Report (2004)ꜛ identified over 11,000 victims of clerical abuse in the U.S. Catholic Church from 1950 to 2002.

- Australia: The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017)ꜛ estimated at least 15,000 victims.

- Ireland: The Murphy and Ryan Reportsꜛ documented thousands of cases, particularly in Catholic-run institutions.

- Latin America: Investigations in countries like Chile, Mexico, and Argentina have uncovered extensive abuse networks, often protected by Church leadership.

- Other regions: Cases have been reported across Canada, the Philippines, and African nations, with investigations revealing similar patterns of abuse and cover-ups.

These figures, though staggering, are likely conservative estimates, as many victims never come forward.

The system of concealment

The Catholic Church has operated a sophisticated system of concealment to protect abusive clerics and its own reputation rather than safeguarding victims. When an allegation was made, Church authorities often followed a set protocol designed to minimize scandal rather than deliver justice. Key elements of this system include:

- Internal investigations: Rather than involving civil authorities, bishops or internal Church tribunals handled allegations, often dismissing them as misunderstandings or exaggerations.

- Reassignment rather than punishment: Instead of defrocking or reporting abusers to law enforcement, the Church frequently transferred them to different parishes, dioceses, or even countries. Often, the pedophilic priests continued with their abuse at their new locations.

- Non-disclosure agreements and silencing victims: Survivors who came forward were often pressured into silence through legal settlements or spiritual coercion.

- Destroying or withholding records: Reports from various countries indicate that Church officials systematically destroyed documents related to abuse allegations or refused to cooperate with law enforcement.

- Blaming external factors: Church leaders have historically attempted to blame clerical celibacy, homosexuality, or modern “moral decay” rather than recognizing institutional responsibility.

In summary, the Church’s response to abuse allegations has been characterized by a pattern of denial, cover-up, and protection of abusers. This systemic concealment has allowed the abuse to continue unchecked for decades – or even centuries – and has inflicted immeasurable harm on countless victims.

Rite of Episcopal Ordination by Shawn McKnight, Jefferson City, 2018. The depicted persons are not related to the abuse scandal. However, I thought, that the depicted scenery – Two church authorities cover the bishop-to-be with a large book, probably a Bible – perfectly symbolizes the systematic cover-up of pedo-criminal figures in the Church. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Dealing with the crimes: The example of France vs. Germany

In the previous section, you may have noticed, that the reported numbers of clerically abused children vary across countries. This discrepancy is not only due to differences in the prevalence of abuse but also to the way investigations are conducted. In the case of France and Germany, the contrast in reported cases is particularly striking and can largely be attributed to differences in investigation methodologies, Church control over inquiries, and societal attitudes toward reporting abuse. While both countries have comparable Catholic Church influence and similar population sizes, the gap in reported cases is striking. France’s independent commission estimated 330,000 victims over 70 years, while Germany’s Church-led investigations only reported 3,677 cases (Catholic) and 9,000 cases (Protestant). The discrepancy strongly suggests that the real numbers in Germany are far higher than officially acknowledged.

Differences in investigation scope and Methodology

The French CIASE report (2021)ꜛ included not only clergy but also lay Church members (teachers, volunteers, etc.), leading to a much broader and more realistic assessment of the scale of abuse. It was an independent commission, gathering extensive victim testimonies and examining external reports.

In contrast, the German Catholic Church’s 2018 reportꜛ was Church-led, relying solely on internal records, which meant that cases were underreported or omitted entirely. A 2024 Protestant Church studyꜛ revealed 9,000 cases, but like the Catholic report, it did not apply a broad victim-centered methodology. If Germany had used the same approach as France, the number of reported cases would likely be hundreds of thousands.

Different levels of Church control over investigations

A key factor in the discrepancy is who controls the investigation. In France, the government mandated an independent review, ensuring transparency. The CIASE report revealed far higher numbers than Church-led investigations typically produce.

In Germany, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference controlled the inquiry, limiting its scope to Church records. Many cases remained unrecorded or were actively destroyed to protect the institution. This practice mirrors other Church-led investigations worldwide: in the U.S. (John Jay Report, 2004ꜛ), Australia (Royal Commission, 2017ꜛ), and Ireland (Murphy Report)ꜛ, independent investigations revealed exponentially more cases than Church-controlled inquiries.

Cultural and legal factors influencing reporting rates

France’s secularism (laïcité) fosters a stronger anti-clerical tradition, which has likely played a significant role in encouraging survivors to report their abuse. In a society where public trust in Church institutions is lower, victims may feel less social pressure to remain silent and are more inclined to seek justice. The culture of secular governance provides a framework where Church influence over legal proceedings is minimal, making it easier for cases to be investigated thoroughly and independently.

In contrast, Germany maintains a closer Church-state relationship, notably through the Kirchensteuer (Church Tax) system, which financially ties citizens to the institution. This economic entanglement may contribute to a reluctance among victims to report their abuse, fearing both social and legal consequences. The Church’s continued influence in public and political life could further discourage survivors from coming forward, as they may perceive the justice system as being partial to ecclesiastical authorities rather than prioritizing their testimonies.

Furthermore, the statute of limitations in Germany has historically been stricter than in France, preventing many older victims from seeking justice for crimes committed decades ago. In contrast, France’s more extensive investigation included cases from long past, recognizing the lifelong trauma inflicted upon survivors. This difference in legal frameworks has had a significant impact on the number of reported cases, allowing France to uncover a much broader scope of abuse than Germany, where many incidents may never legally surface.

Underreporting and survivor reluctance

Studies suggest that many survivors never report their abuse, especially in Church settings where victims may feel powerless. The real number of victims in Germany is likely much higher than the officially reported 12,677 cases (Catholic + Protestant). If we apply the French prevalence rate to Germany’s Catholic population, hundreds of thousands of victims could have suffered abuse.

Another major factor is clergy mobility: the Catholic Church systematically transferred abusive clerics rather than defrocking or prosecuting them, making it harder to track abusers and their victims. Many cases were covered up in different dioceses, ensuring that some crimes were never documented.

Summary

The true scale of child sexual abuse within the German Catholic Church is likely far greater than official reports suggest. Historical evidence from Germany, Ireland, and Australia demonstrates that Church-led investigations consistently underreport the extent of clerical abuse, as they prioritize institutional protection over transparency. The German Church’s reliance on internal records has severely limited the accuracy of reported numbers, whereas independent inquiries, such as the French CIASE report, have revealed exponentially higher figures.

Had Germany undertaken an independent, victim-centered investigation comparable to France’s, the estimated number of abused children would likely be in the hundreds of thousands rather than the officially acknowledged figures. The discrepancy underscores the deep-seated control the Church exercises over such inquiries, allowing for the suppression of records and discouragement of survivor testimonies.

The comparatively low numbers in Germany are not indicative of a lower incidence of abuse but rather reflect a systematic failure to fully investigate and acknowledge the scope of these crimes. The combination of institutional control, legal barriers, and survivor reluctance has contributed to the severe underreporting of these atrocities, leaving countless victims without justice or recognition.

Estimating the total numbers of abused children

The reported numbers of child sexual abuse by Christian clerics only account for periods where investigators had access to documents, records were still available, and witnesses were alive to testify. However, Christianity and its hierarchical institutions date back far longer, meaning the actual scale of clerical abuse over history is likely far greater than current estimates suggest.

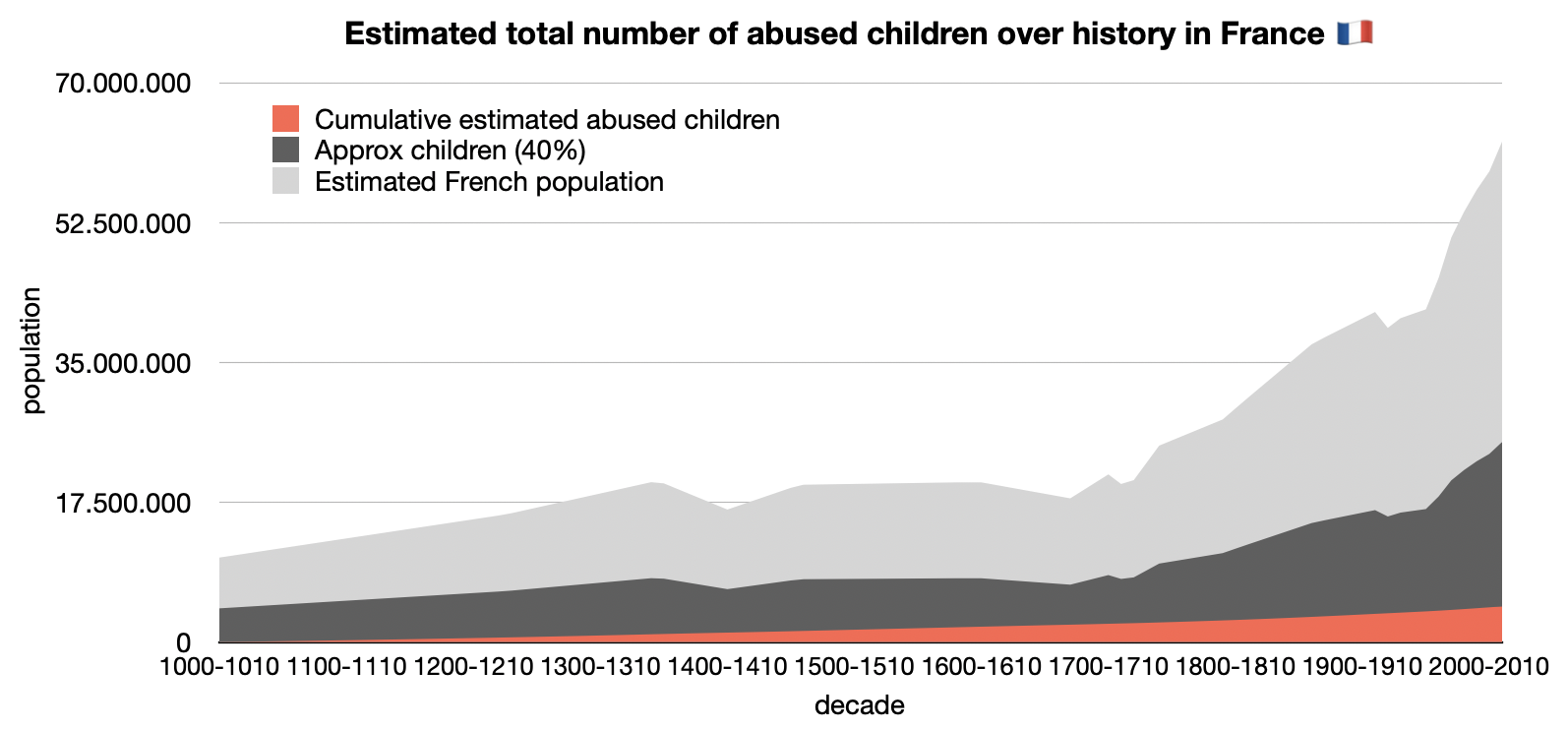

To approximate the total number of Christian clerical child abuse cases over history, we undertake a retrospective analysis based on available data and population estimates. To do so, we take the investigated number of abused children from France between 1950 and 1960 (80,000 cases) as a reference, as French reports appear to be the most accurate estimates as discussed before. This decade is particularly useful as it marks the first period of secular investigation, before media and ecclesiastical control likely led to a reduction in abuse in the following years. That is, the figures from 1950-1960 are probably the closest to those of previous decades, before public awareness forced the clergy and state to act.

In 1950-1960, the French population was approximately 42 million (sourceꜛ). Assuming a 40% child population (sourceꜛ), this results in an estimated 16.8 million children. Using these values, we calculate the abuse rate per child per decade as:

\[\text{Abuse rate per decade} = \frac{80,000}{16,800,000} = 0.0047619\]Using this abuse rate per decade, we can extrapolate backwards to estimate historical abuse levels. Since exact population data for each decade is unavailable, we interpolate values from available data (sourceꜛ). For our estimation, we start from the year 1000 CE as we assume the institutional Church was well-established by this time. We use interpolated population estimates for each decade and apply the abuse rate to calculate the number of abused children. The cumulative total is the sum of all estimated cases up to that point:

Estimated total number of abused children since 1000 CE in France (all values rounded; shortened excerpt; full table available in this Numbers tableꜛ)

| Decade | Estimated French population | Approx. children (40%) | Estimated abused children | Cumulative estimated abused children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000-1010 | 10,590,426 | 4,236,170 | 20,172 | 20,172 |

| 1010-1020 | 10,829,787 | 4,331,915 | 20,628 | 40,800 |

| 1020-1030 | 11,069,149 | 4,427,660 | 21,084 | 61,884 |

| $\qquad\vdots$ | $\qquad\vdots$ | $\qquad\vdots$ | $\qquad\vdots$ | $\qquad\vdots$ |

| 2000-2010 | 58,914,286 | 23,565,714 | 112,218 | 4,364,478 |

| 2010-2020 | 62,640,000 | 25,056,000 | 119,314 | 4,483,792 |

Caution (!)

This table anything but a precise calculation. The numbers are based on a single decade of French data and assume both a constant abuse rate and a constant child population percentage over time. It does not account for variations in reporting rates, social attitudes, or other factors that could significantly affect the numbers. Differences in gender ratios, age distributions, and other demographic factors could also influence the results. The purpose of this exercise is to illustrate the potential scale of the issue over centuries, not to provide an exact count. However, further research and refinement of these figures are necessary in order to gain a more accurate understanding of the historical prevalence of clerical abuse.

Cumulative number of abused children in France since 1000 CE. Shown are the interpolated population estimates and estimated child population (40%) per decade along with the cumulative total of abused children. All values are rounded and can be downloaded from this Numbers tableꜛ.

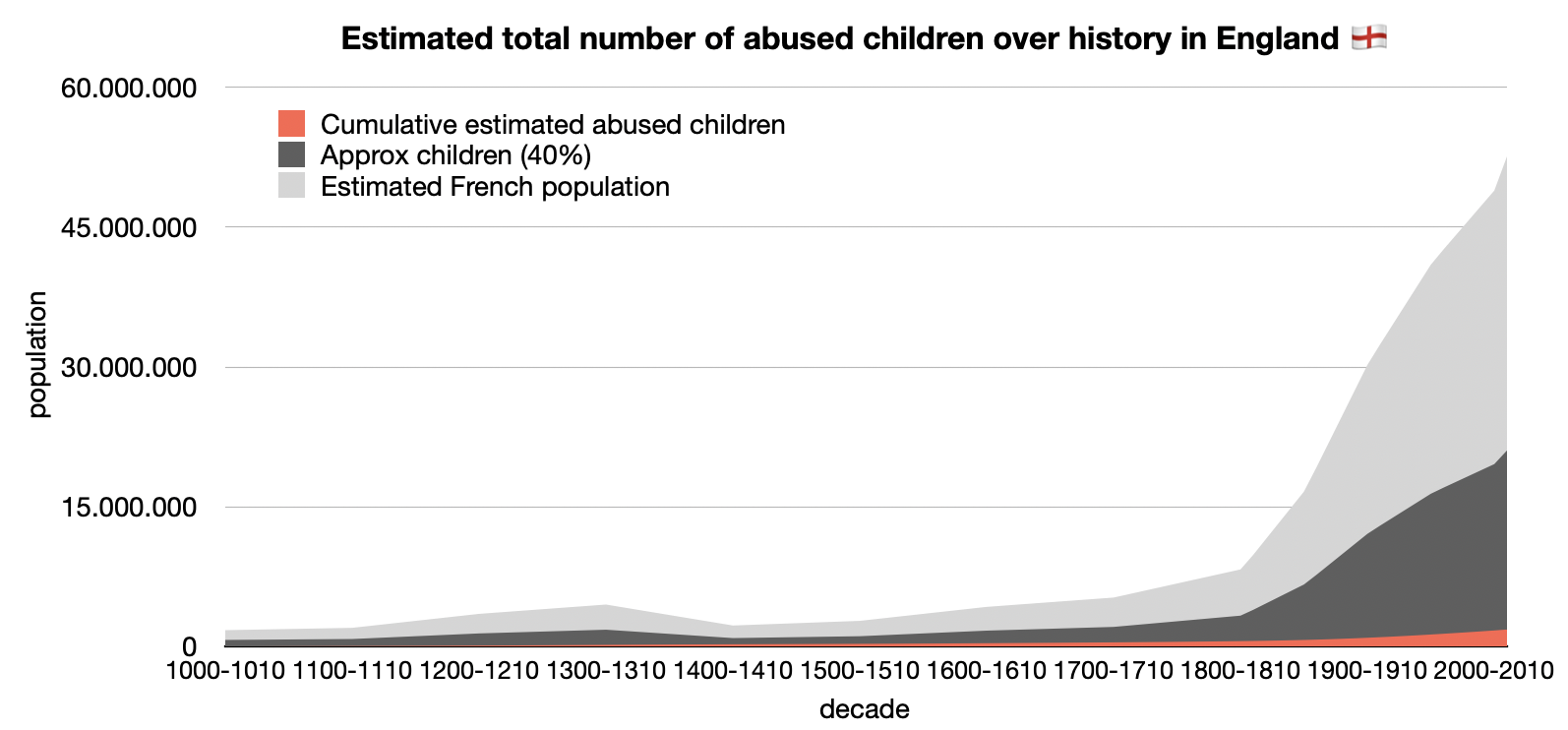

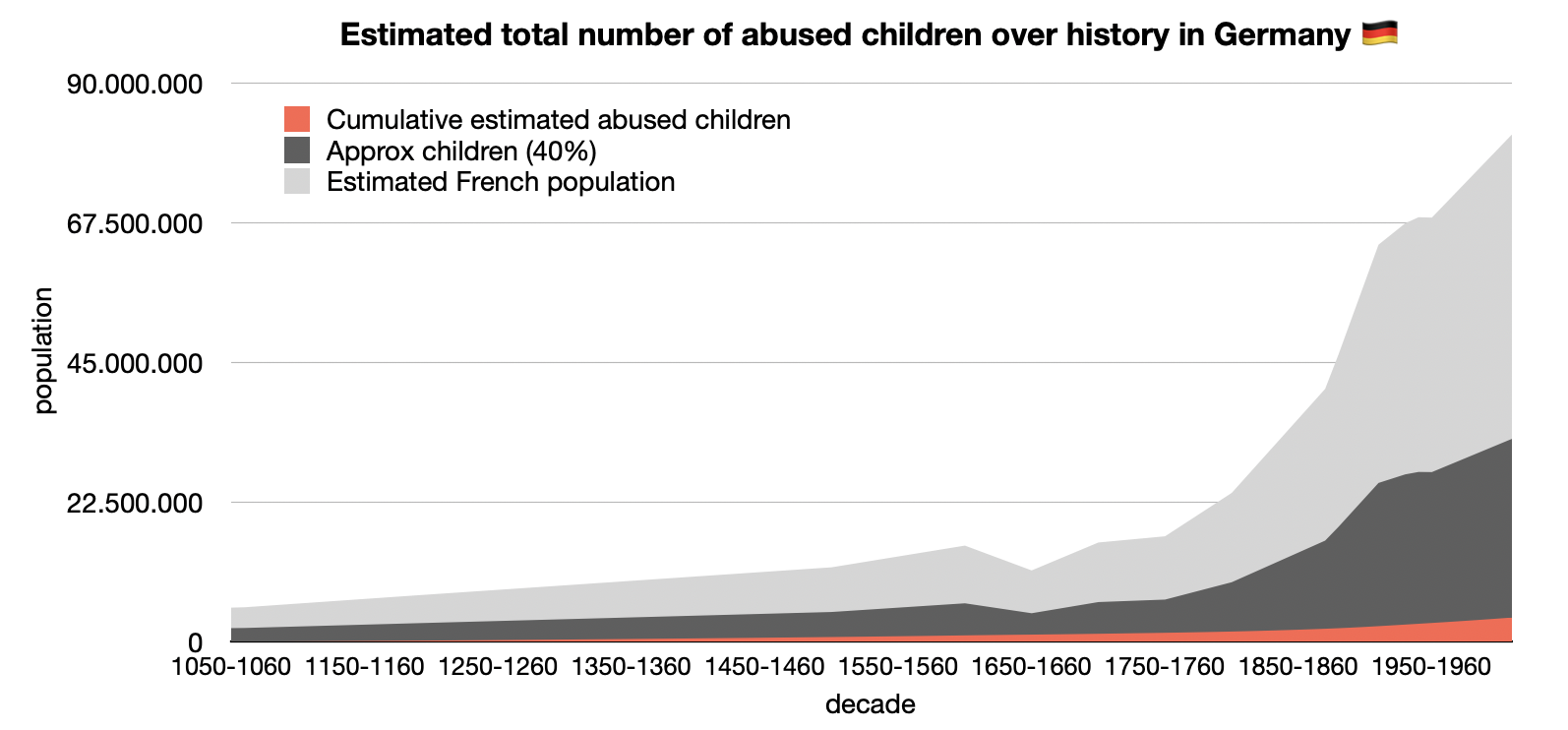

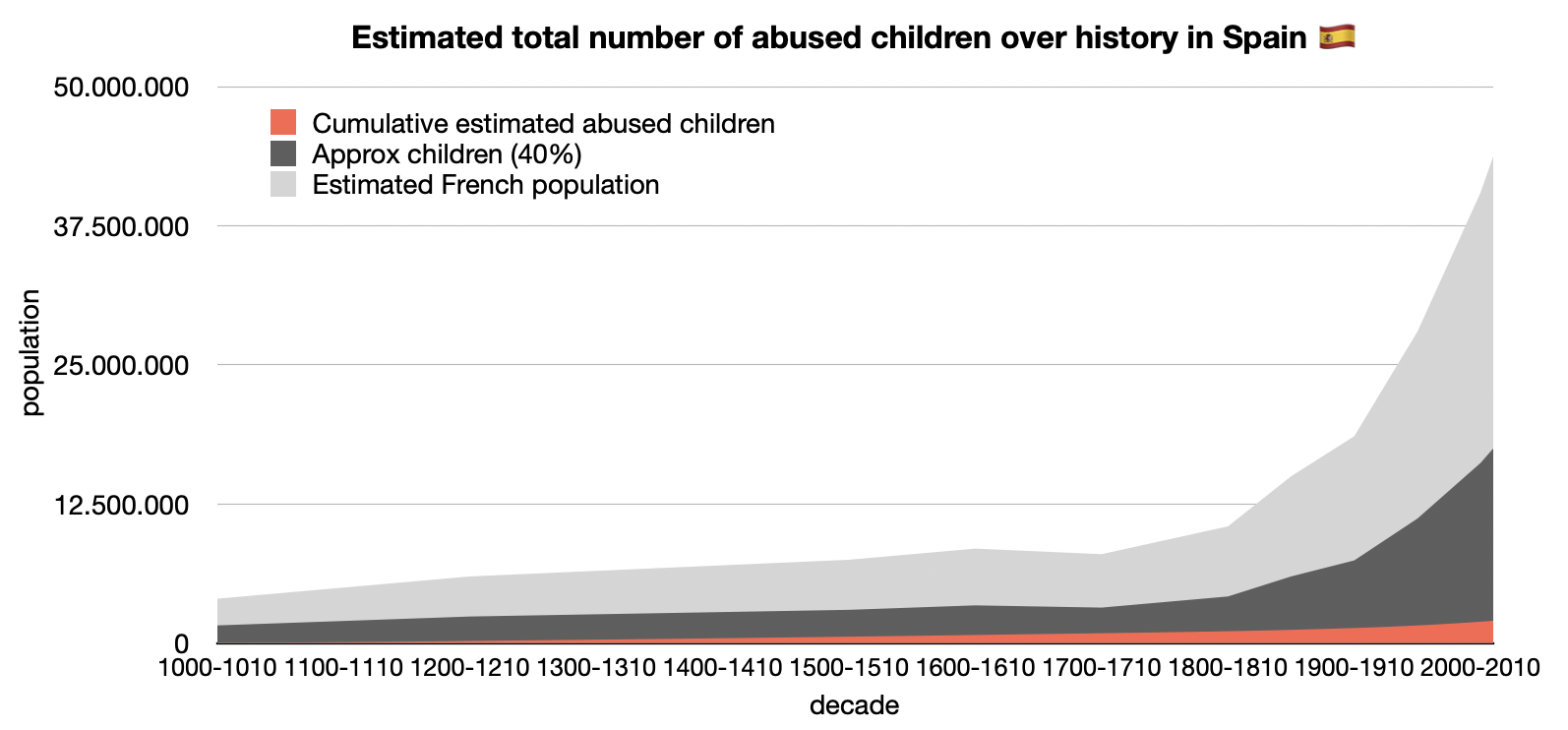

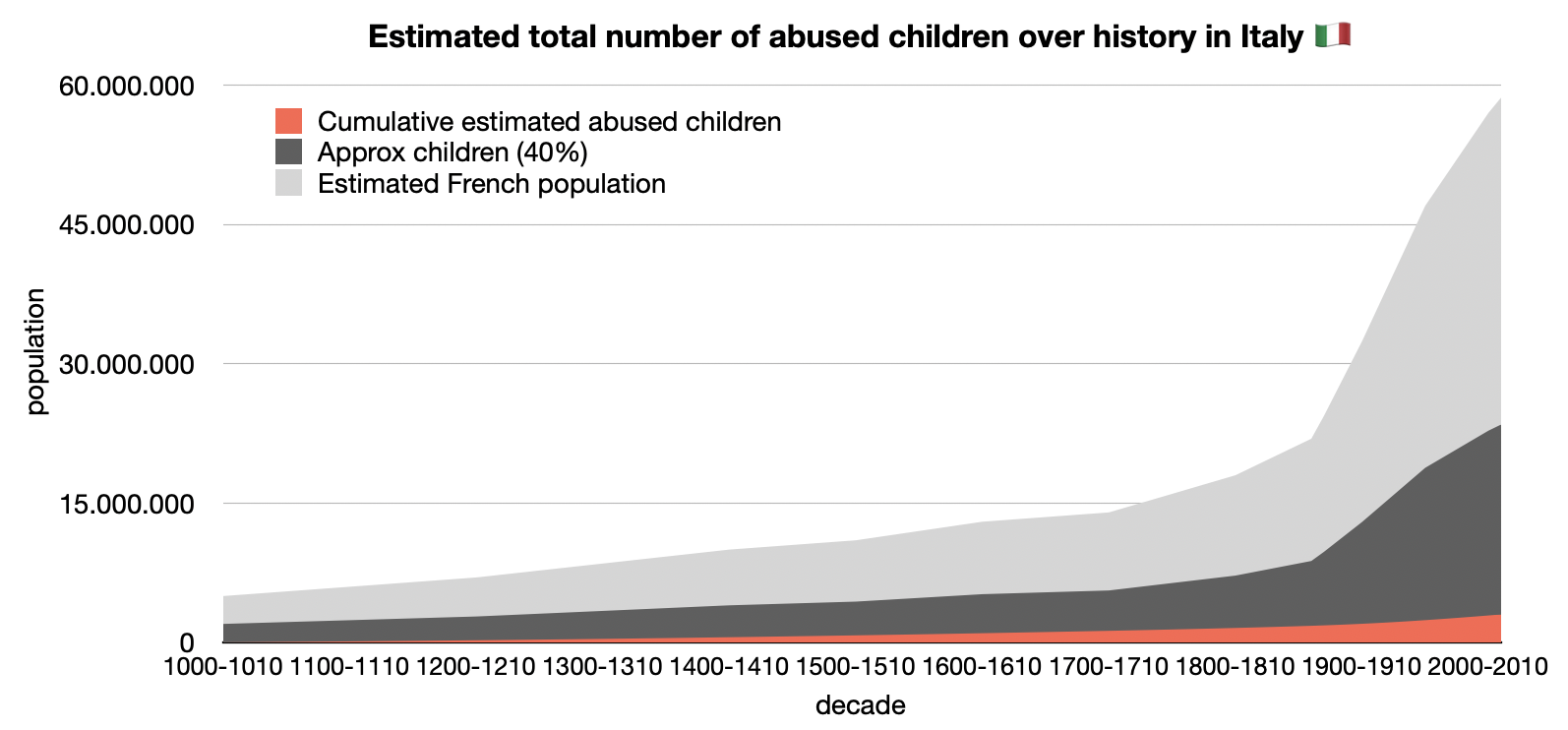

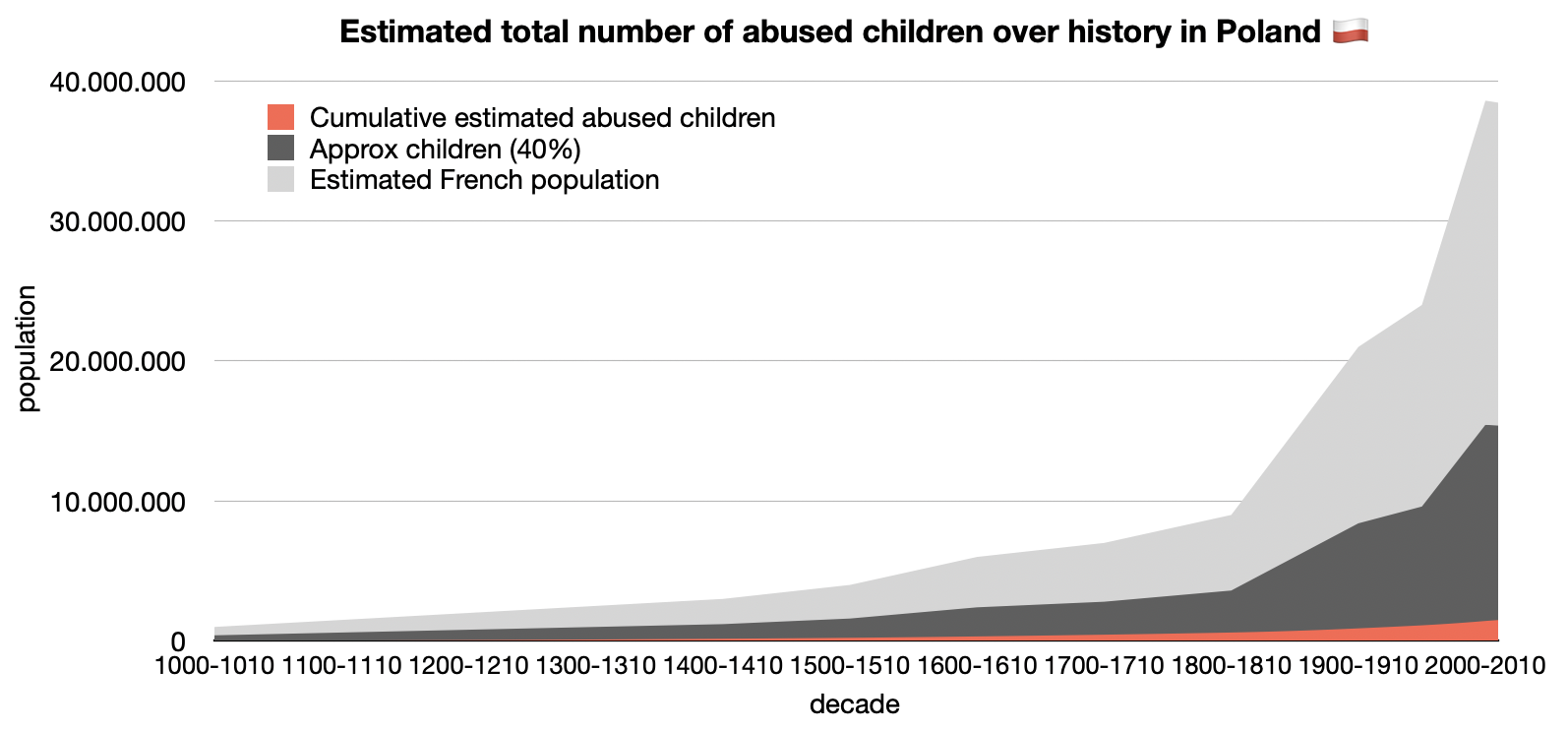

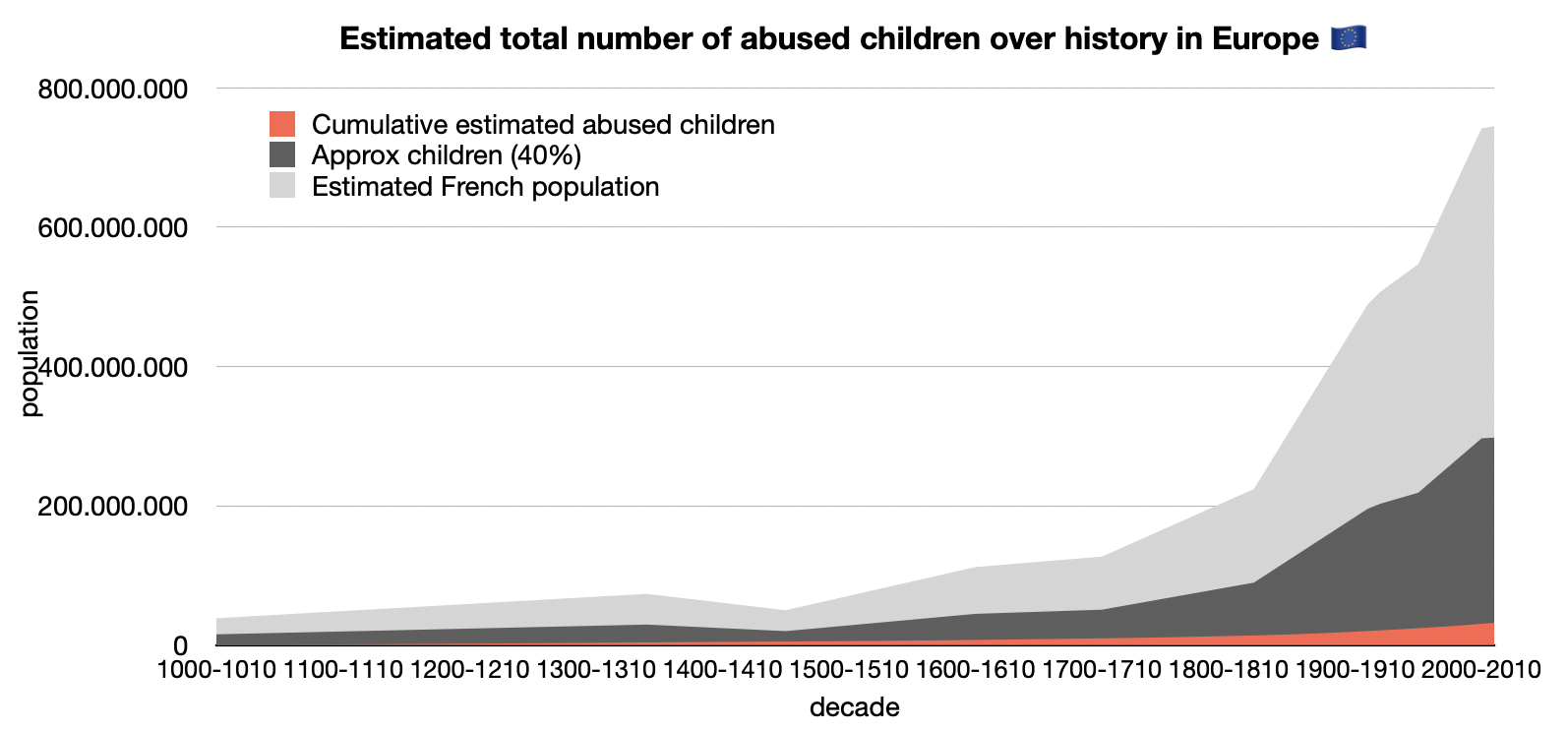

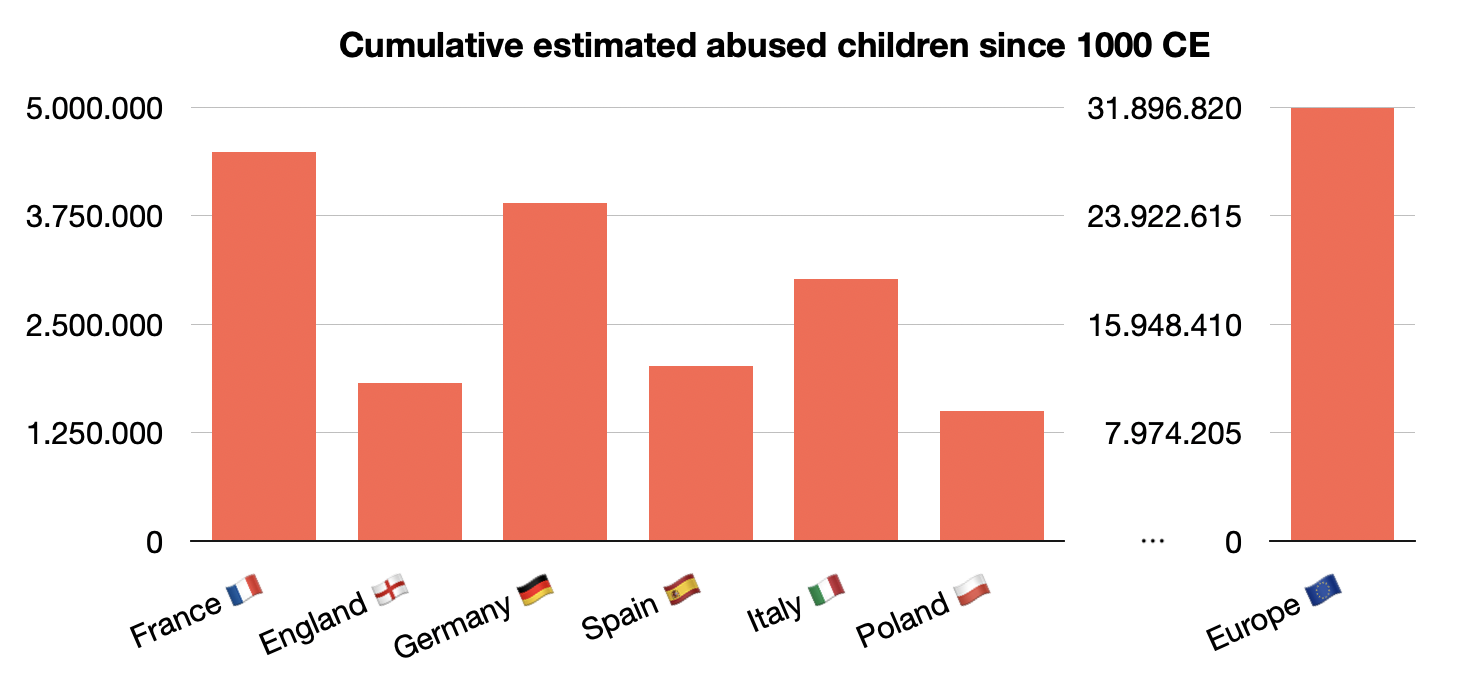

As a result of our very rough estimation, we find that the total number of abused children just in France since 1000 CE could be in the range of 4.5 million. After seeing the scale of abuse in a single country over a millennium, I asked myself: What about other major countries in Europe with a strong Christian presence, such as Germany, Italy, Spain, or Poland? Thus, I repeated the same calculation for these countries and for Europe as a whole. The results are summarized in the following plots, showing the population, estimated child population, and cumulative abused children for each decade from 1000 to 2020. All values are rounded and can be downloaded from this Numbers tableꜛ:

Cumulative numbers of abused children in England, Germany, Spain, Italy, Poland, and Europe as a whole since 1000CE. Shown are the interpolated population estimates and estimated child population (40%) per decade along with the cumulative total of abused children. All values are rounded and can be downloaded from this Numbers tableꜛ. The respective sources of the population data are listed in the references.

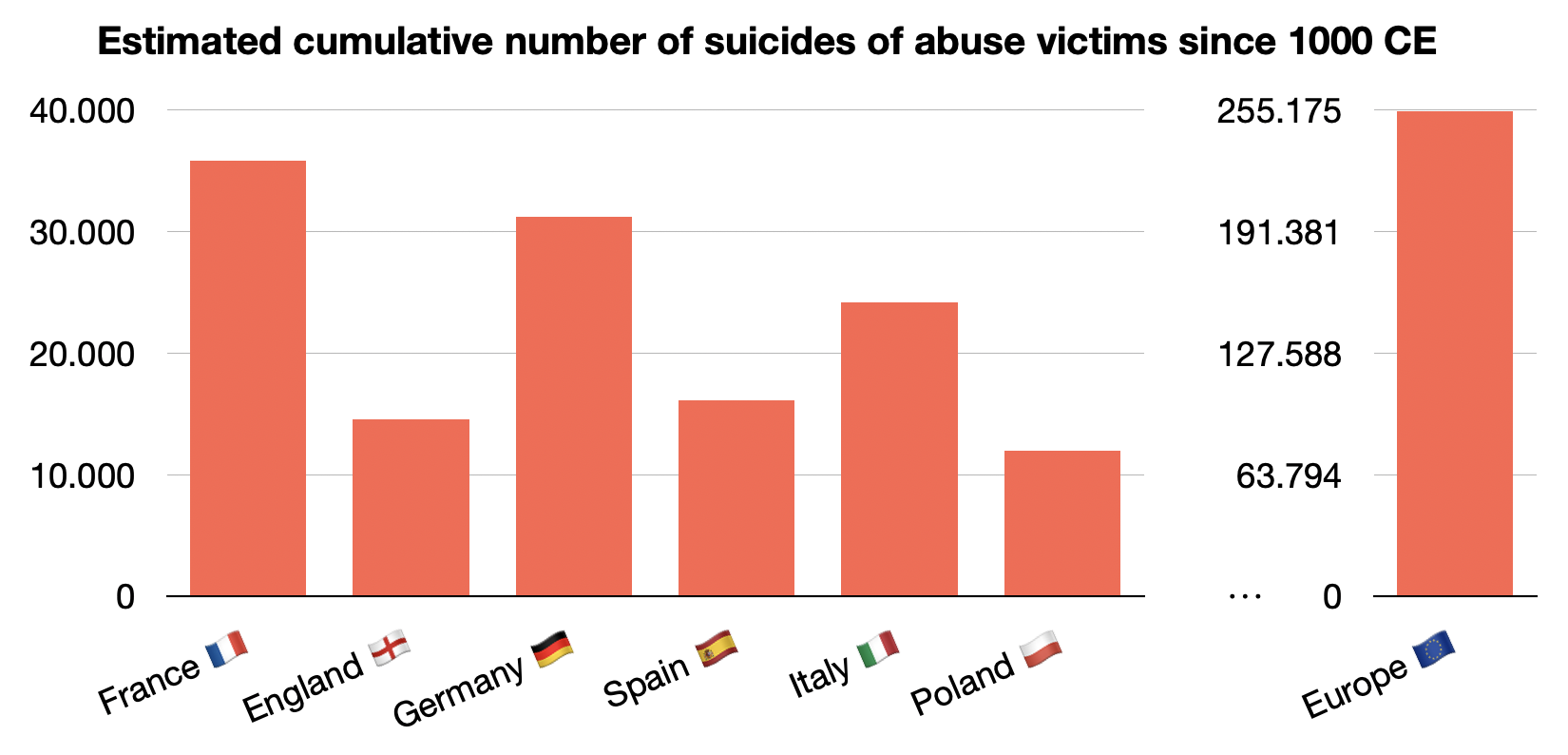

Let’s plot the total cumulative number of abused children for each country and Europe just to get a sense of the scale of the issue:

Cumulative number of abused children in France since 1000CE. Shown are the interpolated population estimates and estimated child population (40%) per decade along with the cumulative total of abused children. Plotted values are rounded and can be downloaded from this Numbers tableꜛ.

Again, these numbers are based on rough estimates and interpolations. They are not based on concrete data from each decade but rather on the assumption of a constant abuse rate and child population percentage. The actual numbers could be significantly higher or lower, depending on various factors such as reporting rates, social attitudes, and demographic changes. However, the results provide a sobering perspective on the potential scale of clerical abuse over centuries – and the shown numbers only account for Europe. The global scale of this issue, considering the presence of Christianity worldwide, is likely far greater. Wether over- or underestimating the actual numbers, the potential sheer number of abused just for Europe, roughly 32 million children, is a staggering and deeply troubling figure. Behind each digit of this enormous sum lies a life shattered by abuse, a childhood stolen, and a trust betrayed. The true extent of this tragedy may never be fully known, but the urgency of addressing it is undeniable. And the subsequent consequences of each abuse can in some cases go beyond the direct physical and psychological harm.

Beyond the direct physical and psychological consequences for each individual victim, every case of abuse also carries the risk of encouraging suicidal behavior. Assuming a conservative suicidal rate of 0.8% as estimated by a study in France (Choquet et al., 1997ꜛ), we can estimate the number of suicides due to clerical abuse in Europe since 1000 CE:

Estimated cumulative number of suicides due to clerical abuse in Europe since 1000CE. Again, these numbers are based on rough estimates and interpolations and should be interpreted with caution. Plotted values are rounded and can be downloaded from this Numbers tableꜛ.

These numbers reveal another dimension of the clerical abuse: the potential loss of life due to the psychological trauma inflicted on victims. Christian clerics who abused children have not only caused immeasurable suffering during their victims’ lives but may also have indirectly contributed to the loss of life. In Europe as a whole, the estimated number of suicides due to clerical abuse could be in the range of 256,000. An institution, claiming to represent the essence of moral and ethical values, has in fact been responsible for a tragedy of an unbearable scale. The Church’s failure to protect the most vulnerable and its systematic cover-up of these crimes have led to a legacy of pain and suffering that extends far beyond the individual victims, as each abuse case also has a ripple effect on families, communities, and societies. The long-term societal impact of such widespread abuse is immeasurable.

Calls for accountability and reform

The revelations of widespread abuse have prompted calls for reform, but the Catholic Church has failed to make meaningful structural changes. While some policies have been introduced — such as stricter guidelines on handling allegations — these reforms remain superficial. The core issue remains that the Church prioritizes its own survival over justice for victims. Despite public apologies, it continues to resist fundamental reforms. One major point of contention is the persistent practice of internal investigations rather than full cooperation with civil authorities. Without external oversight, the Church retains control over the process, often minimizing accountability and shielding offenders from justice. Additionally, demands for the release of all records related to abuse cases remain largely unanswered. Many critical documents are hidden or even destroyed, preventing full transparency regarding the extent of the abuse and those responsible for the cover-ups.

Priest preaching in front of his flock. The investigations of clerical child abuse have revealed a dark side of the Church’s power and authority, showing how it has been used to protect abusers rather than safeguarding the vulnerable. It exposed that the Church holds only one thing as truly sacred: itself, rather than the victims. Source: 12019ꜛ on Pixabayꜛ

Another crucial aspect is the issue of accountability for bishops and other high-ranking officials who knowingly concealed cases of abuse. While some individual clerics have faced consequences, there has been little to no institutional reckoning for the leadership that facilitated these crimes. The Vatican has attempted to respond to the crisis with measures such as Vos Estis Lux Mundi (2019), a directive aimed at improving internal Church accountability. However, this reform remains largely ineffective as it still entrusts investigations to Church authorities, rather than ensuring true legal oversight by secular judicial bodies. The measures also fail to mandate the automatic reporting of abuse cases to civil authorities, allowing the Church to continue handling crimes internally. Additionally, survivors and advocacy groups have criticized these reforms as mere gestures meant to restore public confidence rather than to bring meaningful justice. Without binding external accountability and the full cooperation of the Church with legal authorities, these reforms will continue to serve as little more than symbolic efforts to mitigate scandal rather than eradicate abuse.

What the Church’s behavior reveals about its stance on morality and self-perception

The systemic abuse of children and the Church’s handling of these crimes provide profound insights into the institution’s actual moral stance. While the Church publicly proclaims itself as a moral authority, advocating for virtue, compassion, and justice, its actions in these abuse scandals expose a stark contrast. Rather than addressing these crimes with honesty and accountability, the Church has demonstrated a consistent pattern of self-preservation at the cost of human suffering.

Stained glass of an altar boy. It were often the most vulnerable members of the congregation who fell victim to clerical abuse. In the immediate vicinity of clerics, they were particularly exposed to the predatory behavior of abusive priests and other church officials and church laypersons. Source: Thomasꜛ on Pixabayꜛ

The whole institutional structure of the Church, particularly within Catholicism, adds another layer to its self-identity. The fact that there was an established system for dealing with and covering up incidents of abuse shows that abuse is not just an unfortunate consequence of individual moral failings but something deeply embedded in the institution itself. This systemic approach — whether deliberate or not — demonstrates that the Church as an organization has long prioritized its own survival over addressing these egregious crimes. The persistence of these cover-ups and the intricate internal mechanisms designed to protect abusive clerics point to an institutional complicity that far exceeds passive negligence.

Choir dress of a cardinal. While this dress is commonly associated with moral integrity and authority, it reminds the victims of clerical abuse of their terrible suffering they have experienced at the hands of those who wore it. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

At its core, this is about power. Christian authority figures have historically wielded power over others through their self-exalted claim to be the supreme moral and ethical authority on Earth. However, morality and ethics, as preached by the Church, serve merely as tools for maintaining and exerting control rather than principles that the institution itself abides by. The ability to set the moral framework while remaining exempt from its application allows the Church to operate under a double standard, wherein its own actions remain largely unchallenged. This hypocrisy erodes the very foundation of its moral legitimacy, exposing its ethical teachings as a pretext for authority rather than a genuine commitment to justice and righteousness.

Stone statue of a priest or cardnial in front of a church, demonstrating the power and authority of the clergy. Source: Tania Van den Berghenꜛ on Pixabayꜛ

By fostering this structure, the Church has inadvertently — or perhaps intentionally — created an environment that not only enabled but also attracted pedo-criminals. The knowledge that the institution would shield perpetrators rather than protect victims made it a sanctuary for those seeking to exploit their position for sexual predation. The systemic concealment of crimes and the repeated reassignment of abusive priests to new locations ensured that they could continue their predation with impunity. Even today, the Church remains reluctant to fully dismantle this protective framework, demonstrating that its priorities lie not in ensuring justice but in preserving its power and status.

Conclusion

The sexual abuse of children within Christian institutions, particularly the Catholic Church, is not just a tragic anomaly but an institutional failing that spans centuries. The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that abuse was not only tolerated but systematically covered up, revealing the Church’s primary concern: the preservation of its own power and reputation over the well-being of its most vulnerable members.

The widespread and deeply embedded nature of clerical abuse challenges the Church’s self-image as a moral authority. Instead of serving as a beacon of righteousness, it has proven itself to be an institution capable of great harm, hiding behind doctrines of faith while shielding abusers from justice. The persistence of internal investigations, secrecy, and legal maneuvering to avoid accountability further underscores the Church’s failure to live up to its professed ethical and spiritual values.

Despite mounting evidence and public outcry, meaningful reform remains elusive. Superficial policy changes and apologies do not constitute true accountability, nor do they address the extensive damage inflicted upon victims and their families. The Church’s reluctance to fully confront its history of abuse and cover-ups raises serious questions about its commitment to justice and morality. Until the Church prioritizes transparency, full cooperation with secular legal systems, and genuine institutional reckoning, it cannot claim moral legitimacy.

The Catholic Church, and by extension all other Christian institutions implicated in similar abuses, must face a fundamental choice: continue to evade justice and risk total moral bankruptcy – which, in my opinion, has already occurred –, or embrace true reform and work toward meaningful restitution for survivors. True reform, however, cannot be achieved by half-measures or internal oversight alone. It would require a complete dismantling of the current Church power structure, eliminating the ability of clerical hierarchies to police themselves. Only full transparency, independent investigations, and secular legal intervention can ensure justice for victims and prevent future abuses. As long as the Church maintains its exclusive authority over its own affairs, these atrocities will not only continue but will remain hidden behind layers of institutional protection. The choice, then, is not only for the Church but for the broader society — whether to continue tolerating an institution that shields perpetrators or to demand that it finally be held accountable by the same laws that govern all other institutions.

References and further reading

- Jean-Marc Sauvé, Laetitia Atlani-Duault, Nathalie Bajos, Thierry Baubet, Sadek Beloucif, et al., Sexual Violence in the Catholic Church France 1950 – 2020 Final Report French Independent Commission on Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church (CIASE), Commission Indépendante sur les Abus Sexuels dans l’Eglise, 2021, hal-03948252ꜛ

- Sexueller Missbrauch an Minderjährigen durch katholische Priester, Diakone und männliche Ordensangehörige im Bereich der Deutschen Bischofskonferenzꜛ

- Wikipedia article on ForuM – Forschung zur Aufarbeitung von sexualisierter Gewalt und anderen Missbrauchsformen in der Evangelischen Kirche und Diakonie in Deutschlandꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the John Jay Report (2004)ꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017)ꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Murphy and Ryan Reportsꜛ

- Population and demographics data of France:

- Population and demographics data of Germany:

- Our world in data: Population of Germanyꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the History of Germanyꜛ

- Britannica article on German society, economy, and culture in the 14th and 15th centuriesꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Holy Roman Empireꜛ

- Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschungꜛ

- statista.com: Entwicklung der Bevölkerung auf der Fläche des Deutschen Kaiserreiches in den Jahren von 1816 bis 1910ꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Liste der Volkszählungen in Deutschlandꜛ

- Population and demographics data of England:

- Population and demographics data of Poland:

- Population and demographics data of Italy:

- Population and demographics data of Spain:

- Population and demographics data of Europe as a whole:

- Choquet M, Darves-Bornoz JM, Ledoux S, Manfredi R, Hassler C., Self-reported health and behavioral problems among adolescent victims of rape in France: results of a cross-sectional survey, Child Abuse Negl., 1997 Sep;21(9):823-32. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00044-6ꜛ, PMID: 9298260ꜛ

- Karlheinz Deschner, Das Kreuz mit der Kirche. Eine Sexualgeschichte des Christentums, 1974, Econ, Düsseldorf 1974; überarbeitete Neuausgabe 1992; Sonderausgabe 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811483-9-8

- Doyle, T. P., Sipe, A. W. R., & Wall, P. J., Sex, priests, and secret codes: The Catholic Church’s 2,000-year paper trail of sexual abuse, 2006, Taylor Trade Publishing, ISBN: 978-1566252652

- Frawley-O’Dea, M. G., Perversion of power: Sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, 2007, Vanderbilt University Press, ISBN: 978-0826515476

- Kieran Tapsell, Potiphar’s wife: The Vatican’s secret and child sexual abuse, 2024, C & F Press, ISBN: 978-0645221794

- Hans Günter Hockerts, Die Sittlichkeitsprozesse gegen katholische Ordensangehörige und Priester 1936–1937. Eine Studie zur nationalsozialistischen Herrschaftstechnik und zum Kirchenkampf, 1971, Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, ISBN: 3-7867-0312-4

- Fritz Leist, Der sexuelle Notstand und die Kirchen, 1972, Herder, ISBN: 3-451-01923-X

- Elinor Burkett, Frank Bruni, Das Buch der Schande: Kinder, sexueller Missbrauch und die katholische Kirche, 1995, ISBN: 3-203-51242-4

- Stephen Joseph Rossetti, Wunibald Müller, Sexueller Mißbrauch Minderjähriger in der Kirche. Psychologische, seelsorgliche und institutionelle Aspekte, 1996, Mainz, ISBN: 978-3-7867-1920-5

- Stephen Joseph Rossetti, Wunibald Müller, Auch Gott hat mich nicht beschützt. Wenn Minderjährige im kirchlichen Milieu Opfer sexuellen Missbrauchs werden, 1998, ISBN: 978-3-7867-2099-7

- Doris Wagner, Spiritueller Missbrauch in der katholischen Kirche, 2019, Herder, ISBN: 978-3-451-38426-4

- Rotraud A. Perner, Missbrauch: Kirche – Täter – Opfer, 2010, Lit Verlag, ISBN: 978-3-643-50163-9

comments