Was Martin Luther truly a Christian?

Martin Luther, the central figure of the Protestant Reformation, is often hailed as a revolutionary who sought to return Christianity to its roots – however such roots are defined – by challenging the perceived corruption and doctrinal excesses of the Catholic Church. His legacy is both profound and polarizing, but one question that deserves exploration is whether Luther himself lived up to the very Christian standards he aimed to defend. From a theological and moral standpoint rooted in the teachings of Jesus Christ, Luther’s actions, writings, and attitudes raise significant doubts about whether he embodied the principles of Christianity as defined by the authors of the Gospels.

Martin Luther, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1520, engraving, on laid paper with watermark. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The teachings of Jesus as a benchmark

To evaluate Luther against Christian standards, it is essential to first clarify what those standards entail. According to the New Testament, Jesus emphasized several core principles that form the foundation of his teachings:

- Love and compassion: The command to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31) and even to “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44) is central to Jesus’ moral vision.

- Forgiveness: Jesus taught forgiveness without limit, as seen in his instruction to forgive “seventy times seven” (Matthew 18:22).

- Humility: Jesus modeled humility, emphasizing service over power. He washed his disciples’ feet and declared, “Whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant” (Matthew 20:26).

- Non-violence: Jesus rejected violence, instructing his followers to “turn the other cheek” (Matthew 5:39) and rebuking Peter for drawing a sword during his arrest (Matthew 26:52).

- Freedom from hatred: Jesus consistently denounced hatred, calling instead for unity, peace, and reconciliation.

To assess Luther’s adherence to Christian principles, we must examine his actions, writings, and attitudes in light of these core values. By comparing his behavior to the ethical standards set by the Gospels, we can evaluate whether Luther embodied the spirit of Christianity he sought to reform.

Luther’s actions and writings in the light of the Gospels

In the following, we explore several aspects of Luther’s life and work that raise ethical questions when viewed through the lens of Jesus’ teachings as depicted in the Gospels. These include Luther’s intolerance and hostility, his endorsement of violence, his alignment with power structures, his persecution of social outsiders, his arrogance, and his intemperance. By examining these aspects, we can assess whether Luther’s actions and attitudes align with the ethical standards set by Jesus and whether he truly embodied the principles of Christianity he sought to uphold.

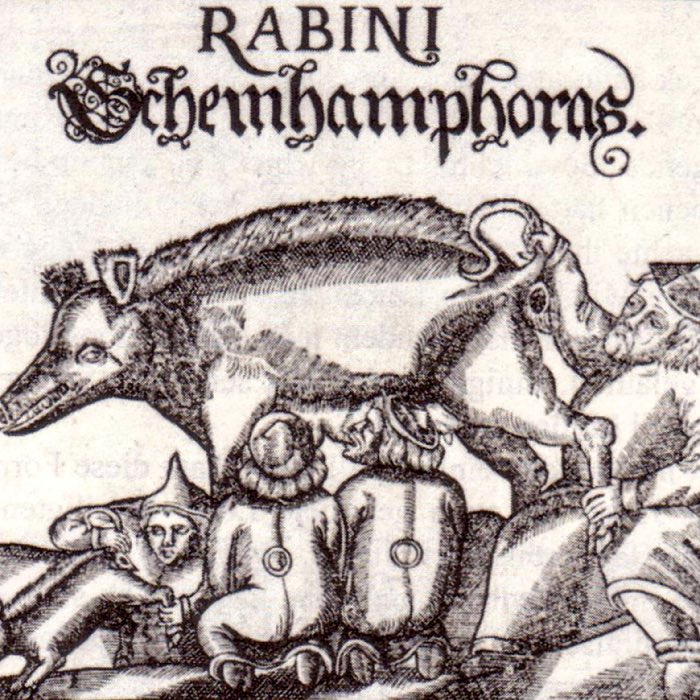

Intolerance and hostility

Luther’s writings often brim with hostility, particularly toward those he deemed heretical or opposed to his reforms. His infamous treatises against the Jews, such as On the Jews and Their Lies, contain vitriolic language advocating for the destruction of synagogues, expulsion of Jews, and even violence. This rhetoric starkly contradicts Jesus’ teaching to love one’s neighbor and enemy alike. However, Luther’s anti-Jewish sentiments stand in line with a long tradition of Christian anti-Semitism. Christianity always sought to distance itself from Judaism in order to legitimize itself as a separate religion. This led to the demonization of Jews as “Christ murders” and “enemies of God”. Luther’s writings, while extreme, were part of this broader trend of anti-Jewish sentiment in Christian history. Nevertheless, as he claims to be a reformer, his failure to challenge this tradition is a significant moral failing.

Additionally, in some of his Table Talks, Luther went so far as to endorse the euthanasia of disabled children, referring to them as “spawn of the devil” and suggesting that they should be drowned. This shocking stance, dehumanizing the most vulnerable, stands in direct contradiction to Jesus’ emphasis on compassion and care for the weak, further calling into question Luther’s adherence to Christian ethical principles.

Unforgiveness and violence

Luther’s call for the violent suppression of the Peasants’ Revolt in 1525, encapsulated in his tract Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants, reveals a profound departure from the Christian ethic of forgiveness. Rather than advocating for understanding or seeking peaceful resolution, Luther encouraged the nobility to crush the revolt mercilessly, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands of peasants.

This stance demonstrates a prioritization of social and political order over the spiritual principles of mercy and reconciliation that Jesus championed. Jesus consistently taught forgiveness as a central tenet of faith, famously urging his followers to forgive others not just seven times, but “seventy times seven” (Matthew 18:22). He also exemplified this virtue on the cross, praying for those who crucified him, saying (Luke 23:34): “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do”. Luther, by contrast, showed little interest in extending such mercy to those he viewed as disruptive or heretical. His rhetoric often called for extreme punishment rather than reconciliation. His approach toward theological dissenters, including Anabaptists, Catholics, and even rival Protestant reformers such as Ulrich Zwingli, Andreas Karlstadt, and the leaders of the Anabaptist movement, was one of condemnation rather than dialogue. His attacks on those who opposed him did not leave room for repentance or understanding but instead sought their exclusion, persecution, and even execution.

Power and hierarchy

While Luther criticized the wealth and corruption of the Catholic Church, his relationship with secular authorities often mirrored the hierarchical structures he sought to dismantle. His alignment with German princes was crucial in securing the success of the Reformation, as he relied on their protection to defy papal authority. Notably, he allied with Frederick the Wise of Saxony, who provided him refuge in Wartburg Castle after the Diet of Worms in 1521 (where Luther was declared an outlaw by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). Later, Luther supported the establishment of state-controlled churches (e.g., in the Augsburg Confession of 1530), reinforcing secular rulers’ authority over religious matters. His endorsement of the violent suppression of the Peasants’ Revolt in 1525 further demonstrated his reliance on secular power, as he urged the nobility to crush the rebellion mercilessly, aligning himself with the ruling elite rather than the oppressed peasantry. All these measures not only ensured the survival of his movement but also entrenched power dynamics that contradicted the egalitarian spirit of early Christianity.

Luther’s acceptance of state power as a tool to enforce religious conformity — often at the expense of dissenters — further distanced him from Jesus’ model of humility and servant leadership.

Violence and persecution

Luther’s endorsement of state violence to enforce religious orthodoxy stands in direct opposition to Jesus’ call for non-violence (Matthew 5:39, “But I say to you, do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.”) and forgiveness (Luke 23:34, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”). His support for the persecution of Anabaptists (a movement of Christians who advocated adult baptism in the 16th century), whom he regarded as dangerous radicals, led to their imprisonment, torture, and execution. He called for violence against peasant revolts, the murder of women accused of performing ‘magic’ — many women who were healers and midwives were accused of being witches in Christian fanaticism — and the killing of non-Christians such as the Turks. Luther even asserted that a Christian who killed a Turk would be immediately sanctified and enter heaven:

“…for the hand that wields the sword and kills is no longer the hand of man, but the hand of God.”

– Martin Luther, Zur Frage, ob man auch als Soldat in einem Gott wohlgefälligen Stand lebt

These declarations illustrate his deep departure from Christianity’s self-proclaimed core values of peace and compassion.

Luther himself acknowledged the suffering and bloodshed his preaching had caused, yet he absolved himself of responsibility, claiming divine command:

“I have slain all the peasants in the uprising. All their blood is on my hands. But I place it upon our Lord God. He has commanded me to speak this way.”

– Martin Luther, Tischreden

This statement reflects a complete perversion of Jesus’ teachings, which emphasized personal responsibility, humility, and peace. Claiming to act on direct divine command to justify mass violence is a stark contradiction to the principles of love and forgiveness at the heart of Christianity, exposing a deep hypocrisy and arrogance in Luther’s self-perception as a religious leader. It also unmasks Luther as a fanatical preacher filled with hate and anger rather than being an ethically motivated reformer.

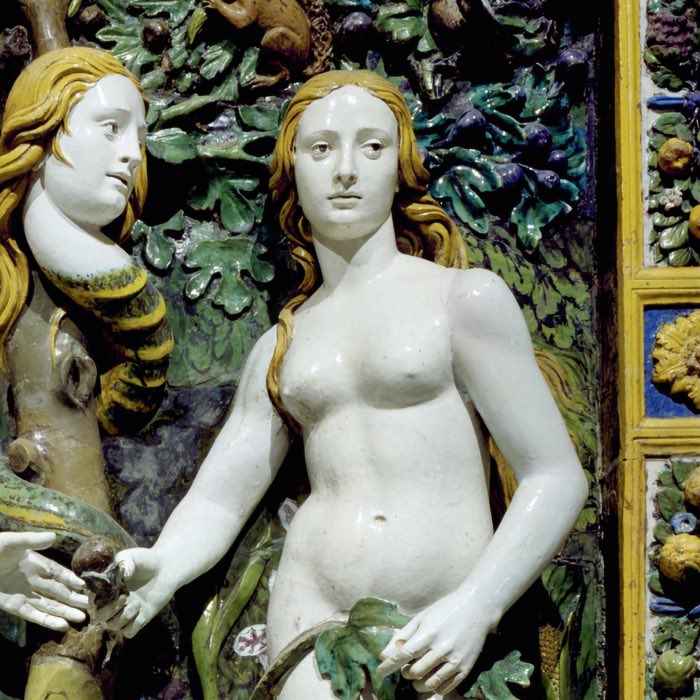

Exclusion and persecution of social outsiders

Luther’s writings also reveal a troubling stance toward social outsiders, including usurers and prostitutes, whom he called to be excluded, persecuted, tortured, or even executed. This is in stark contrast to the examples set by Jesus, who embraced those marginalized by society. Jesus openly associated with tax collectors and money changers — figures widely despised in his time — and showed compassion toward prostitutes, as seen in his interaction with the woman (traditionally identified as a prostitute) who anointed his feet in Luke 7:36–50. Furthermore, Jesus emphasized that such individuals were not beyond redemption, stating:

“Truly I say to you: The tax collectors and prostitutes enter the kingdom of God sooner than you.”

– Jesus (Matthew 21:31)

Luther, however, took a much harsher stance. He condemned usurers, advocating severe punishments against them, and regarded prostitutes as irredeemable, demanding their harsh persecution rather than offering them a path to spiritual renewal. His approach stands in direct contradiction to the inclusiveness of Jesus’ message, which emphasized redemption over condemnation. In contrast, Jesus warned against harsh judgment:

“Judge not, that ye be not judged. For by what judgment you judge, you will be judged, and by what measure you measure, it will be measured to you.”

– Jesus (Matthew 7:1-2)

This highlights the moral inconsistency in Luther’s stance on social outsiders. While Jesus sought out sinners, tax collectors, and prostitutes — offering them a path to redemption — Luther’s writings reflect a more rigid and punitive attitude. His focus on divine wrath over divine mercy fundamentally contrasts with the compassion and forgiveness Jesus consistently preached.

Luther’s arrogance

Luther’s writings and statements reveal a profound sense of self-importance, as he positioned himself as the ultimate authority on Christian doctrine, refusing any form of criticism or alternative interpretation. He boldly declared:

“I will have my teaching without judgment from anyone, even from all the angels. … Whoever does not accept my teaching may not be saved. For it is God’s and not mine; therefore my judgment is God’s and not mine.”

– Martin Luther, Wider den falsch genannten geistlichen Stand des Papstes und der Bischöfe

These statements showcase an alarming level of arrogance, equating his personal theological views with divine will. Such an attitude contradicts Jesus’ teachings on humility, self-reflection, and the rejection of self-exaltation. Jesus consistently taught that no human should assume absolute authority over matters of salvation, emphasizing servitude over dominance:

“For whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

– Jesus (Matthew 23:12)

Unlike Luther, Jesus never demanded blind submission to his teachings but rather invited people to seek understanding and live by the spirit of compassion and humility. Jesus’ message was rooted in open-hearted engagement, not in rigid dogma imposed under the threat of exclusion or condemnation. Luther’s claims that rejecting his doctrine equated to rejecting God starkly contrast with Jesus’ willingness to meet people where they were, embracing doubt, discussion, and personal growth.

Luther’s intemperance

Initially, Luther was highly critical of extravagant and excessive lifestyles, condemning gluttony and indulgence. However, as he grew older, his own habits changed dramatically. He became a notable consumer of large quantities of food and, particularly, alcohol. His letters and Table Talks reveal a fondness for beer and heavy meals, and some contemporaries noted that his indulgence in these excesses was in stark contrast to his earlier calls for moderation. Luther’s intemperance raises questions about his personal discipline and the consistency of his moral teachings, especially considering the Christian emphasis on self-control and temperance.

The theological dilemma

Luther’s emphasis on sola fide (faith alone) as the means of salvation raises another question about his alignment with Christian teachings. While this doctrine highlights the primacy of faith, it arguably diminishes the importance of moral action and ethical behavior as integral components of Christian life. Luther himself reinforced this perception through statements such as

“Sin boldly, but believe more boldly!”

– Martin Luther, Letter to Philip Melanchthon, August 1, 1521

and

“Thus we are in ourselves sinners and yet […] justified by faith.”

– Martin Luther, Scholien zum Römerbrief (1515/1516)

or

“Thus we see that a Christian man has enough in faith; he needs no work to be pious. If he no longer needs works, he is certainly released from all commandments and laws; if he is released, he is certainly free. This is Christian freedom, the only faith that makes it so, not that we can walk idly or do evil, but that we need no works to attain to godliness and salvation …”

– Martin Luther, Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen

These statements suggest a dangerous moral relativism, where faith alone is seen as overriding ethical conduct, contradicting Jesus’ insistence on the necessity of moral integrity and righteous actions.

Jesus’ teachings, as recorded in the Gospels, emphasize a harmony between faith and action. His parables, such as the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37), illustrate the necessity of compassionate deeds, while his admonition in Matthew 7:21,

“Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father”

– Jesus (Matthew 7:21)

underscores the centrality of moral action. Furthermore, Jesus warned against empty faith without action:

“…and whoever hears these sayings of mine and does not do them is like a foolish man who built his house on sand.”

– Jesus (Matthew 7:26)

This highlights that, according to Jesus’ teachings, true faith must be accompanied by righteous conduct, a principle that contrasts with Luther’s emphasis on faith alone.

By prioritizing faith over works, Luther’s theology risks reducing Christianity to a belief system devoid of the transformative ethical practices that Jesus advocated.

Summary: Was Martin Luther truly a Christian?

After examining Luther’s actions, writings, and attitudes in light of the core values of Christianity, a critical question emerges: Was Martin Luther truly a Christian? Let’s therefore summarize our analysis by comparing Luther’s behavior with the ethical standards set by the Gospels:

| Christian value | Met by Luther? | Luther’s interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Love and compassion | ❌ No | Luther advocated hatred and violence against dissenters, Jews, and Anabaptists. |

| Forgiveness | ❌ No | Luther called for harsh punishments and execution of rebels and heretics. |

| Humility | ❌ No | Luther declared his teachings as absolute, rejecting criticism. |

| Non-violence | ❌ No | Luther supported war against Turks, execution of Anabaptists, and the suppression of peasants. |

| Acceptance of outcasts | ❌ No | Luther condemned social outsiders rather than offering redemption. |

| Equality all people | ❌ No | Luther’s alignment with secular power reinforced social hierarchies. |

| Self-control | ❌ No | Luther indulged in excesses, contradicting his earlier calls for moderation. He also actively allowed his own anger to be his inner drive. |

| Humility | ❌ No | Luther’s arrogance and self-importance contradicted Jesus’ model of servant leadership. |

| Action rather than faith | ❌ No | Luther emphasized faith alone (sola fide) while disregarding ethical conduct and good works. |

From this analysis, it is clear that Luther did not embody fundamental ethical teachings of Christianity. Instead of practicing love, humility, and reconciliation, he often chose division, intolerance, and coercion. If being a true Christian is measured by adherence to the core principles set forth by Jesus, Luther falls far short of this standard. Instead of being a beacon of Christian morality, he emerges as a fervent and often ruthless figure whose actions contradict the very faith he sought to reform.

Conclusion

Luther’s legacy is undeniably complex. His theological contributions reshaped Christianity, challenging the abuses of the Catholic Church and democratizing access to scripture. However, his personal actions and rhetoric often diverged from the principles he sought to defend.

From a Christian perspective rooted in the teachings of Jesus, Luther’s advocacy for violence, intolerance, and division raises significant ethical concerns. His alignment with political power and his prioritization of doctrinal purity over compassion and humility reveal a profound tension between his reformist ideals and the moral principles of Christianity.

While Luther championed faith and challenged religious corruption, his endorsement of violence, his intolerance toward dissenters, and his alignment with state power stand in stark contrast to the values of love, forgiveness, humility, and non-violence that Jesus espoused. His theological doctrine of sola fide placed faith at the center of salvation, yet his own life raises critical questions about the relationship between faith and ethical conduct.

Luther’s advocacy for persecution, his role in sectarian violence, and his divisive rhetoric highlight the contradictions within his moral stance. Our above analysis demonstrated that he did not embody the ethical and moral principles of Christianity as defined within the Gospels – the very text he sought to place in the center of his reform movement. His actions and rhetoric, driven by an uncompromising zeal and a willingness to enforce doctrine through coercion and violence, stand in stark opposition to Christianity’s self-proclaimed virtues of love, forgiveness, and humility. Instead of exemplifying the compassion and grace, Luther’s legacy is marred by an aggressive pursuit of religious purity that fostered persecution and exclusion rather than unity and redemption.

So, if Luther was not a true Christian, then what was he? Rather than a figure of spiritual enlightenment, Luther emerges as a fanatic preacher, consumed by fury and hatred, using religious rhetoric to justify violence, persecution, and the suppression of dissent. His teachings, far from promoting universal love and salvation, contributed to an enduring legacy of division and cruelty.

Map showing worldwide Protestantism in 2010. If the Protestant perceive themselves as the true Christians, they should critically reflect on the legacy of Martin Luther. If the founder of their movement did not embody the core values of Christianity, what does this say about the movement itself? I think, only by acknowledging the moral failings of its founder can Protestantism truly live up to the ethical standards it claims to uphold. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

But, to be fair, no Christian religious leader in history has ever fully embodied the ethical core values Christianity has defined for itself. The ideals of love, forgiveness, and humility, as preached by Jesus, have often been compromised in favor of power, doctrine, and institutional survival. While Luther’s failings are particularly stark, they are not unique in the broader history of Christian religious leadership. His case serves as a powerful reminder of how religious movements, even when grounded in reformist ideals, can become entangled in the same authoritarianism and intolerance they claim to oppose.

Our critique invites a broader reflection on the nature of religious leadership: Can a reformer’s contributions to theology excuse actions that undermine the moral tenets of their faith? Luther’s case demonstrates that intellectual and theological influence do not necessarily equate to moral exemplarity. His legacy serves as both a catalyst for Christian transformation and a cautionary tale of how power and ideology can distort the very principles they claim to defend.

References and further reading

- Martin Luther, Von den Juden und ihren Lügen, 1543, Facsimile Publisher, 2016, ISBN: 978-9333628044

- Martin Luther, Tischreden, 1986, Reclam, ISBN: 978-3150012222

- Martin Luther, Wider die mörderischen und räuberischen Rotten der Bauern, 1525, available online at Bayerische Staatsbibliothekꜛ and on Zeno.orgꜛ (both in German)

- Martin Luther, Zur Frage, ob man auch als Soldat in einem Gott wohlgefälligen Stand lebt, 1526, available onlineꜛ in German

- Martin Luther, Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen, 2020, LIWI Literatur- und Wissenschaftsverlag, ISBN: 978-3965422575

- Martin Luther, Luthers Vorlesung Über Den Römerbrief, 1515/1516, 2018, Forgotten Books, ISBN: 978-0366360581

- Martin Luther, D. Martini Lutheri Exegetica Opera Latina, Vol. 2: Continens Enarrationes in Genesin Cap. X-XV, 2018, Forgotten Books, ISBN: 978-1390228441

- Martin Luther, Predigt über Exodus 22,18 (“Hexenpredigt”), 1526

- Martin Luther, Vom ehelichen Leben, 2023, Sharp Ink, ISBN: 978-8028345273

- Martin Luther, Johannes Ehmann, Confutation Alcorani, 1542, Würzburg: Echter, 1999, ISBN: 3893751777

- Martin Luther, Eine Heerpredigt wider den Türken, 2010, Verlag Classic Edition, ISBN: 978-3839703168

- Günter: Fabiunke, Martin Luther als Nationalökonom. Anhang: Martin Luther, An die Pfarrherrn wider den Wucher zu predigen, Vermahnung, 1540, 1963, Berlin. Akademie-Verlag

- Martin Luther, Brief an Philipp Melanchthon vom 1.8.1521

- Martin Luther, Ernste Vermahn- und Warnschrift Luthers an die Studenten zu Wittenberg, am 13.5.1543 öffentlich an der Kirche angeschlagen, 1543

- Martin Luther, Wider den falsch genannten geistlichen Stand des Papstes und der Bischöfe, 1522

- theologe.deꜛ: This website provides a very detailed comparison of Luther’s quotations with Jesus’ statements in the Gospels

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 9 -Mitte des 16. bis Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vom Völkermord in der Neuen Welt bis zum Beginn der Aufklärung, 2010, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499624438

- Hans-Martin Barth, The Theology of Martin Luther: A Critical Assessment, 2012, Augsburg Fortress, ISBN: 978-0800698751

comments