Did Luther’s antisemitism lay the blueprint for Nazi ideology?

Martin Luther, the central figure of the Protestant Reformation, profoundly shaped the religious and cultural landscape of Europe. His theological innovations challenged the Catholic Church – both theologically and on matters of authority – and laid the foundation for Protestantism. However, his legacy is not without controversy. Among the darker aspects of his influence is the argument that his rhetoric and ideology, particularly his virulent antisemitism, laid the groundwork for the development of Nazi ideology centuries later. While it would be an oversimplification to label Luther the sole or direct “spiritual father” of Nazism, there are undeniable parallels between his writings and the ideological framework that supported the Third Reich.

1938 edition of Martin Luther’s antisemitic writing On the Jews and Their Lies. The cover readings “Concerning the Jews: Away With Them!”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Luther’s antisemitic writings

Luther’s early career was characterized by theological disputes with the Catholic Church, not with Judaism. In his earlier writings, such as That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew (1523), he even expressed a degree of sympathy for Jews, arguing that they might be more receptive to Christianity if treated with kindness and respect. However, as his efforts to convert Jews to Christianity failed, Luther’s attitude shifted dramatically.

By the 1540s, Luther had written some of the most vitriolic antisemitic tracts in European history, including On the Jews and Their Lies (1543). In this infamous treatise, he called for extreme measures against Jews, including:

- The destruction of synagogues and Jewish homes.

- The confiscation of Jewish writings, particularly the Talmud.

- The prohibition of rabbis from teaching.

- The forced labor or expulsion of Jews from Christian territories.

Luther’s language was not merely hostile; it was dehumanizing and incendiary. He referred to Jews as “poisonous envenomed worms” and “children of the devil”. These writings cemented antisemitism within the Protestant tradition in Germany, reinforcing existing prejudices and laying a foundation for future persecution.

The cultural impact of luther’s antisemitism

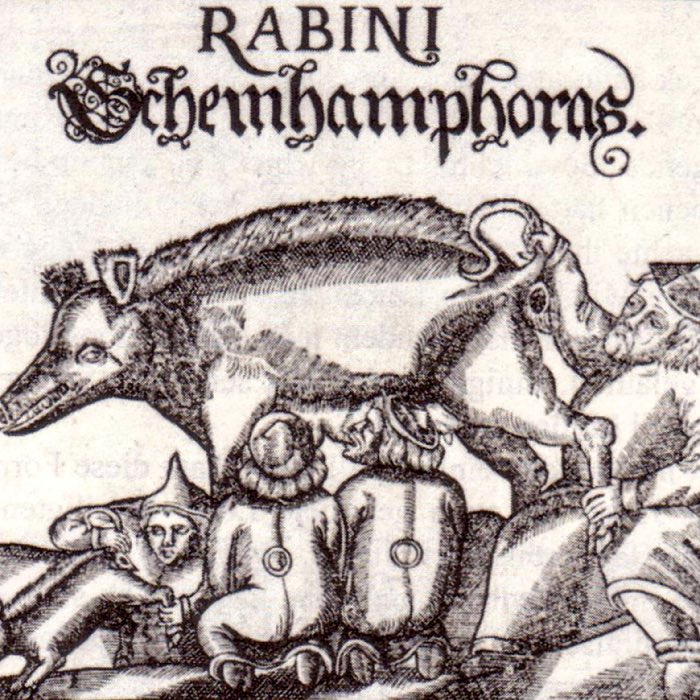

Luther’s antisemitic rhetoric did not exist in isolation. It resonated within a broader European context already steeped in Christian anti-Jewish sentiment. Medieval Europe had a long history of blood libels, expulsions, and forced conversions. Luther’s writings amplified and legitimized these prejudices by cloaking them in theological language and Protestant authority. However, this should not be seen as a justification for his actions. Luther claimed to be acting in the name of Christianity, but his words and deeds contradicted the teachings of Jesus on love, compassion, and forgiveness, revealing that he maybe never truly understood the essence of the faith he sought to reform.

‘Judensau’ relief at the Regensburg Cathedral. The ‘Judensau’ motif depicts Jews in a derogatory and dehumanizing manner, often in the company of pigs, an animal considered unclean in Jewish tradition. It was intended to warn Christians of the allegedly diabolical customs of the Jews, to ostracize, humiliate and mock them and to defame Judaism: there, the pig is considered unclean (tame in Hebrew) and is subject to a religious food taboo. 49 reliefs, sculptures, sculptures or murals with this motif have been documented since 1230, mainly in German-speaking countries, 44 of which are still preserved. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Occurrence of the ‘Judensau’ motif as a sculpture, relief or mural in Central Europe. All known occurrences are indiciated by a black dot. The red dots indicate the (few!) occurrences that have been removed or destroyed. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the centuries following Luther’s death, his antisemitic views became deeply embedded in German culture. Protestant pastors and theologians frequently cited his works as justification for discriminatory policies. This created a continuity of thought that persisted into the modern era, providing fertile ground for the extreme antisemitism of the 20th century.

Nazi appropriation of Luther

The Nazis viewed Luther as a cultural and ideological hero. Adolf Hitler himself reportedly admired Luther’s defiance of authority, particularly his challenge to the Catholic Church. More importantly, the Nazi propaganda machine eagerly exploited Luther’s antisemitic writings to lend historical and theological legitimacy to their policies.

An antisemitic mural featuring a quote from On the Jews and Their Lies published as a postcard for propaganda purposes. The quote reads “Trau keinem Fuchs auf grüner heid, und keinem Jud’ bei seinem Eid” (“Trust no fox on the green heath, and no Jew on his oath””). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

During the 450th anniversary of Luther’s birth in 1933, Nazi officials emphasized Luther’s role as a unifier of German identity. His antisemitic treatises were reprinted and distributed widely, with Nazi ideologues like Julius Streicher, editor of the antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer, citing Luther as a precursor to their own beliefs.

The 450th birthday of Matin Luther in November 1933 was declared a nationwide holiday termed “German Luther Day” and featured public demonstrations by pro-Nazi Christians and speeches by major religious figures, such Protestant Bishop Hossenfelder. The photograph shows these Luther Day celebration in front of the Berlin Palace, including banners with the inscription “DC” with stands for “German Christians” (Deutsche Christen”) and swastikas on the windows. Bishop Hossenfelder gives the speech on the ramp of the Berlin Palace in the Lustgarten. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Luther’s call for the destruction of synagogues and Jewish communities was eerily echoed in the Nazi regime’s policies, from the Kristallnacht pogrom of 1938 to the systemic genocide of the Holocaust. While Luther could not have foreseen the industrialized mass murder of the 20th century, his writings provided a theological framework that the Nazis exploited to devastating effect.

Third Reich war postcard of Martin Luther by the Nazi Winterhilfswerk (WHW) charity organization. The text reads “Ich suche nicht das Meine, sondern allein des ganzen Deutschlands Glück und Heil.” (“I seek not my own, but solely the happiness and salvation of all Germany”). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Ideological parallels between Luther and Nazi antisemitism

There are several ideological parallels between Luther’s antisemitism and Nazi ideology:

- Dehumanization of Jews: Both Luther and the Nazis portrayed Jews as inherently evil, corrupt, and subversive, reducing them to a threat that needed to be eradicated.

- Call for expulsion and destruction: Luther’s advocacy for the expulsion of Jews and the destruction of their institutions aligns with the Nazis’ initial policies before escalating to genocide.

- National identity: Luther’s emphasis on a unified Christian-German identity foreshadowed the Nazis’ use of racial purity and nationalism to define German identity.

- Blame for social ills: Just as Luther blamed Jews for societal and religious problems, the Nazis scapegoated Jews for Germany’s economic woes and political instability following World War I.

We can expand this analysis by directly comparing the antisemitic rhetoric of Luther and the actions taken by the Nazi regime:

| Luther’s rhetoric | Meaning | Echos in Nazi ideology and actions |

|---|---|---|

| “That their synagogues or schools be set on fire. And that which will not burn be heaped up and covered with earth, so that no man shall see a stone or cinder forever. And these things should be done in honor of our Lord and Christianity, so that God may see that we are Christians.” | Luther called for the destruction of synagogues and Jewish schools to erase Jewish presence from society. | During Kristallnacht (1938), Nazi paramilitary forces and civilians burned down over 1,400 synagogues, vandalized Jewish schools, and destroyed Jewish-owned businesses. |

| “Second, that their houses also be likewise broken down and destroyed. For they do the same things inside as they do in their schools. For this they may be put under a roof or in a stable.” | Luther advocated for the destruction of Jewish homes, reducing them to homelessness or forced relocation. | The Nazis forced Jews into ghettos, seized their homes, and eventually deported them to concentration camps, stripping them of private property and personal security. |

| “Third, to take away all their prayer books and Talmud books.” | Luther demanded the confiscation of Jewish religious texts to suppress Jewish faith and cultural identity. | The Nazis orchestrated book burnings, targeting Jewish literature, including the Talmud, in public spectacles meant to erase Jewish heritage. |

| “Fourth, that their rabbis be forbidden, life and limb, to teach any more.” | Luther sought to silence Jewish religious leaders by banning them from teaching their faith. | The Nazis arrested and executed many Jewish religious leaders, forbidding Jewish practices and education in Nazi-occupied territories. |

| “Fifth, that the Jews be deprived entirely of their convoys and roads. For they have no business in the country, since they are not lords, officials, merchants or the like. They should stay at home.” | Luther called for restricting Jewish movement, barring them from travel and commerce. | The Nazis enacted laws prohibiting Jews from public spaces, workplaces, and transportation, isolating them socially and economically. |

| “Sixth, that they be forbidden to take usury, and that all cash and jewels of silver and gold be taken from them.” | Luther encouraged the confiscation of Jewish wealth and financial assets. | The Nazis implemented mass property seizures, forced Jews to surrender their valuables, and froze their bank accounts before deporting them. |

| “Seventh, that the young, strong Jews and Jewesses be given flails, axes, karsts, spades, rocks and spindles, and be made to earn their bread by the sweat of their noses.” | Luther endorsed forced labor for Jewish individuals, reducing them to servitude. | The Nazis exploited Jewish labor in concentration camps and ghettos, subjecting them to grueling work under inhumane conditions, leading to mass death through exhaustion and starvation. |

| “Summa: … that you and all of us … will be relieved of the diabolical burden of the Jews …” | Luther framed the persecution of the Jews as a divine duty to cleanse society of their presence | The Nazis killed six million Jews in the Holocaust, seeking to eradicate Jewish existence from Europe. |

These comparisons illustrate the direct line between Luther’s antisemitic writings and the genocidal policies of the Nazi regime. While Luther’s rhetoric was rooted in theological polemics, their implementation by the Nazi government was part of a broader racial ideology that led to systematic extermination. The echoes of Luther’s hate speech in Nazi propaganda demonstrate how historical prejudices can be revived and weaponized for mass persecution and violence.

Luther’s calls for euthanasia

Beyond his antisemitism, Martin Luther also advocated for the euthanasia of disabled children, a position disturbingly aligned with Nazi-era policies. In his Table Talk and other writings, Luther suggested that children born with severe disabilities were “changelings” or “spawn of the devil” and that they should be put to death. This view, deeply rooted in medieval superstition, found chilling echoes in the Nazi Aktion T4 program, which systematically murdered disabled individuals under the guise of eugenics and racial purity. The ideological link between Luther’s rhetoric and Nazi policies underscores the perils of theological justifications for inhumane practices.

Distinguishing contexts

While the parallels are striking, it is essential to distinguish between Luther’s context and that of the Nazis. Luther operated within a 16th-century religious framework, and his antisemitism was primarily theological. He saw Jews as obstinate opponents of Christianity and believed their rejection of Jesus endangered the spiritual well-being of society.

In contrast, Nazi antisemitism was rooted in racial ideology. It sought to biologically define Jews as inferior and targeted them for extermination regardless of religious conversion or belief. The Nazis appropriated Luther’s theological rhetoric but stripped it of its religious context, weaponizing it for their racial agenda.

Catholic Church collaboration with the Nazis

While Luther’s legacy influenced Protestant circles, the Catholic Church also played a significant role in enabling Nazi policies. The Reichskonkordat, signed in 1933 between the Vatican and Nazi Germany, granted the Church religious “freedom” in exchange for political neutrality, effectively legitimizing the Nazi regime. Additionally, after World War II, elements of the Catholic Church facilitated the escape of Nazi war criminals through clandestine routes known as the Rattenlinien, helping them evade justice. These instances of collaboration highlight the broader complicity of Christian institutions in the atrocities of the Nazi era, further complicating the moral legacy of both Protestant and Catholic histories.

Conclusion

Martin Luther’s antisemitic writings contributed to a long-standing tradition of anti-Jewish sentiment in Germany, and their appropriation by the Nazi regime demonstrates the dangerous potential of ideological misuse. While Luther’s rhetoric was rooted in religious polemics, its dehumanizing nature and calls for violence resonated through centuries, culminating in its exploitation by the architects of the Holocaust.

The ideological parallels between Luther’s antisemitism and Nazi racial policies underscore the troubling continuity between theological prejudice and political extremism. However, it is crucial to differentiate between Luther’s 16th-century theological framework and the Nazis’ racialized exterminationist ideology. The latter stripped Luther’s rhetoric of its religious context, using it instead to legitimize mass murder.

Luther’s legacy forces a critical reassessment of how historical figures are interpreted and utilized. His contributions to Christian theology cannot be separated from the darker aspects of his influence. Recognizing the harm his rhetoric enabled is essential to ensuring that religious and historical discourse does not become a tool for hatred and oppression in the future.

Statue of Luther in the ruins of Dresden in the aftermath of the second World War. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

References and further reading

- Martin Luther, Von den Juden und ihren Lügen, 1543, Facsimile Publisher, 2016, ISBN: 978-9333628044

- Martin Luther, Tischreden, 1986, Reclam, ISBN: 978-3150012222

- Cicero article on “Judenfeind Luther – Die dunkle Seite des Reformators”ꜛ (in German)

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Ericksen, Robert P., Complicity in the Holocaust: Churches and Universities in Nazi Germany, 2012, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1139059602

- Heschel, Susannah, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany, 2010, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691148052

- Nirenberg, David, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, 2018, Head of Zeus, ISBN: 978-1789541168

- Richard Steigmann-Gall, The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521603522

- Oberman, Heiko, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, 1990, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300037944

comments