Faith and fury: Martin Luther’s advocacy for violence

Martin Luther is widely recognized for his theological breakthroughs and his role in reshaping Christianity. However, alongside his reformist ideals lies a deeply troubling aspect of his legacy: his calls for violence against various groups, often coupled with graphic descriptions of torture and brutal punishments. These views, especially as Luther’s influence grew, reflect not only his theological convictions but also his increasing radicalization in later years.

Hanging of two people, detail from a fresco in Sant’ Anastasia in Verona, by Pisanello, 1436–1438. Martin Luther endorsed hanging and many other forms of execution for various groups he deemed heretical or immoral. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Targets of Luther’s violence

Luther’s calls for violence were not limited to Jews or peasants, groups he infamously condemned. His vitriol extended to several other categories of people, including heretics, Anabaptists, and even fellow Protestants who diverged from his theological interpretations.

Heretics and religious dissenters

In a time when doctrinal purity was equated with societal order, Luther was unyielding in his stance against those he deemed heretical. While he initially advocated for religious tolerance during his earlier writings, his position shifted drastically as he gained political and religious influence. He argued that heretics, who deviated from what he perceived as correct Christian doctrine, deserved harsh punishment without trial:

“There is no need to make a fuss about heretics, they can be condemned unheard. And while they perish at the stake, the believer should root out the evil.”

– Martin Luther, Tischreden

Luther’s justification for such violence stemmed from his belief that heresy endangered not only the soul of the individual but also the moral fabric of society. He explicitly stated that heretics should be executed, describing methods such as burning alive as appropriate. He viewed such acts not as cruel but as necessary for the preservation of divine truth and communal stability.

The Anabaptists

One of the groups that drew Luther’s ire was the Anabaptists, a radical reformist faction that rejected infant baptism and advocated for a separation between church and state. Luther saw their practices as both theologically incorrect and socially destabilizing. He deemed their teachings dangerous enough to warrant their eradication, supporting the persecution and execution of Anabaptists by secular authorities:

“Therefore the authorities are undoubtedly guilty … and shall … punish with bodily force and, if the circumstances allow, also with the sword.”

– Martin Luther, Der 82. Psalm durch D.M.L. geschrieben und ausgelegt (1530)

In a letter to rulers, Luther argued that Anabaptists were akin to seditionists who disrupted the divine order. He endorsed their punishment by sword, drowning, or fire, methods that were carried out across Europe with devastating consequences. Luther’s role in legitimizing such brutality underscores the extent to which his reformist zeal could turn into intolerance.

Catholics and rival reformers

Luther’s opposition to the Catholic Church is well known, but his calls for violence also extended to Catholics and rival Protestant groups who resisted his vision for reform:

“If we punish thieves by hanging, murderers by the sword, heretics by fire, why do we not attack these pernicious teachers of corruption much more than popes, cardinals, bishops and the whole sore of Roman sodomy with all kinds of weapons and wash our hands in their blood …?”

– Martin Luther, Zwo harte ernstliche Schriften. Doct. Martini an den Christlichen Leser (1518)

He denounced the Catholic clergy and monks, often portraying them as corrupt agents of a false religion. His inflammatory rhetoric contributed to an environment of hostility and sectarian violence during the Reformation era.

Similarly, Luther was unrelenting in his criticism of reformers such as Ulrich Zwingli and his followers, whose theological interpretations diverged from Luther’s own. While he did not advocate for their physical destruction as vehemently as he did for other groups, his condemnations fueled divisions within the Protestant movement.

Non-Christians

Luther also directed his violent rhetoric toward non-Christians, particularly the Turks. He called for all “true Christians” to fight against them, declaring that righteous Christians should

“joyfully clench their fists and strike courageously, killing, robbing, and doing as much harm as possible.”

– Martin Luther, Eine Heerpredigt wider den Türken (1529)

and

“Where the Turks … believe the Koran with sincerity, they are not worthy to be called human beings.”

– Martin Luther, Confutation Alcorani (1542)

He further claimed that those who died in such battles would be “blessed and holy forever”. This aggressive and militaristic stance contradicted Jesus’ teachings of peace and reconciliation, revealing how Luther’s nationalism and religious dogmatism fueled calls for bloodshed against perceived enemies of Christianity. However, it stands in line with the general Christian justification of violence (“just war”) against non-Christians, as seen in the Crusades and other historical conflicts.

Social outsiders

Luther also demanded the death of usurers, stating:

“Just as we execute highway robbers and murderers, how much more should we break on the wheel and behead all usurers.”

– Martin Luther, An die Pfarrherren wider den Wucher zu predigen (1540)

This position starkly contrasts Jesus’ own approach to tax collectors and money changers, whom he did not condemn to death but rather invited to repentance and inclusion. In Matthew 9:10-13, Jesus is described as dining with tax collectors and sinners, emphasizing that

“I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.”

– Jesus (Matthew 9:10-13)

Likewise, in Luke 19:1-10, Jesus’ encounter with Zacchaeus, a chief tax collector, results in transformation through mercy rather than condemnation.

Additionally, Luther called for the execution of adulterers and prostitutes:

“If I were a judge, I would have such a poisonous French whore broken on the wheel and beheaded.”

– Martin Luther, Ernste Vermahn- und Warnschrift Luthers an die Studenten zu Wittenberg (1540)

This view directly opposes Jesus’ approach, as seen in the Gospel account where he defended a woman accused of adultery and proclaimed:

“Truly, I say to you, the tax collectors and prostitutes enter the kingdom of God before you.”

– Jesus (Matthew 21:31)

Women

Luther also targeted midwives and female healers, whose knowledge of herbal medicine was frequently associated with witchcraft by zealous Christians. He declared:

“You shall not let the witches live… It is a just law that they should be killed.”

– Martin Luther, “Hexenpredigt” (1526)

This contributed to an increase in witch hunts and executions in regions influenced by Lutheran doctrine. Historical records indicate that territories where Lutheranism took hold, such as certain parts of Germany and Scandinavia, saw intensified witch trials and persecutions, often surpassing those in Catholic regions. The fear-driven environment, reinforced by Luther’s rhetoric, played a significant role in legitimizing such brutal practices against women.

Leaflet with the burning of an alleged witch who is said to have burned the town of Schiltach with the devil in 1531. By Stefan Hamer, 1533. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Methods of violence and torture

Luther’s endorsement of violence was often accompanied by graphic descriptions of the methods he deemed appropriate for punishing those he opposed. He was not a passive supporter of execution but an active proponent of brutal methods meant to instill fear and compliance. For example, in his writings against Anabaptists, Luther endorsed their drowning as a symbolic punishment for their rejection of infant baptism. He also supported the use of fire to execute heretics, aligning with the medieval tradition of burning at the stake. His endorsement of such methods was not unique for his time but remains striking in light of his reformist ideals and his claims of being a Christian.

Here is a list of some of the methods of violence and torture Luther endorsed or condoned:

Burning at the stake

Victims were tied to a wooden stake and set on fire, a method often used against heretics and witches.

The burning of a 16th-century Dutch Anabaptist, Anneken Hendriks, who was charged with heresy, Jan Luyken, 1685. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Drowning

A preferred method of execution for Anabaptists who rejected infant baptism was punishment with water. This was enforced in cities like Münster during the radical religious conflicts of the Reformation.

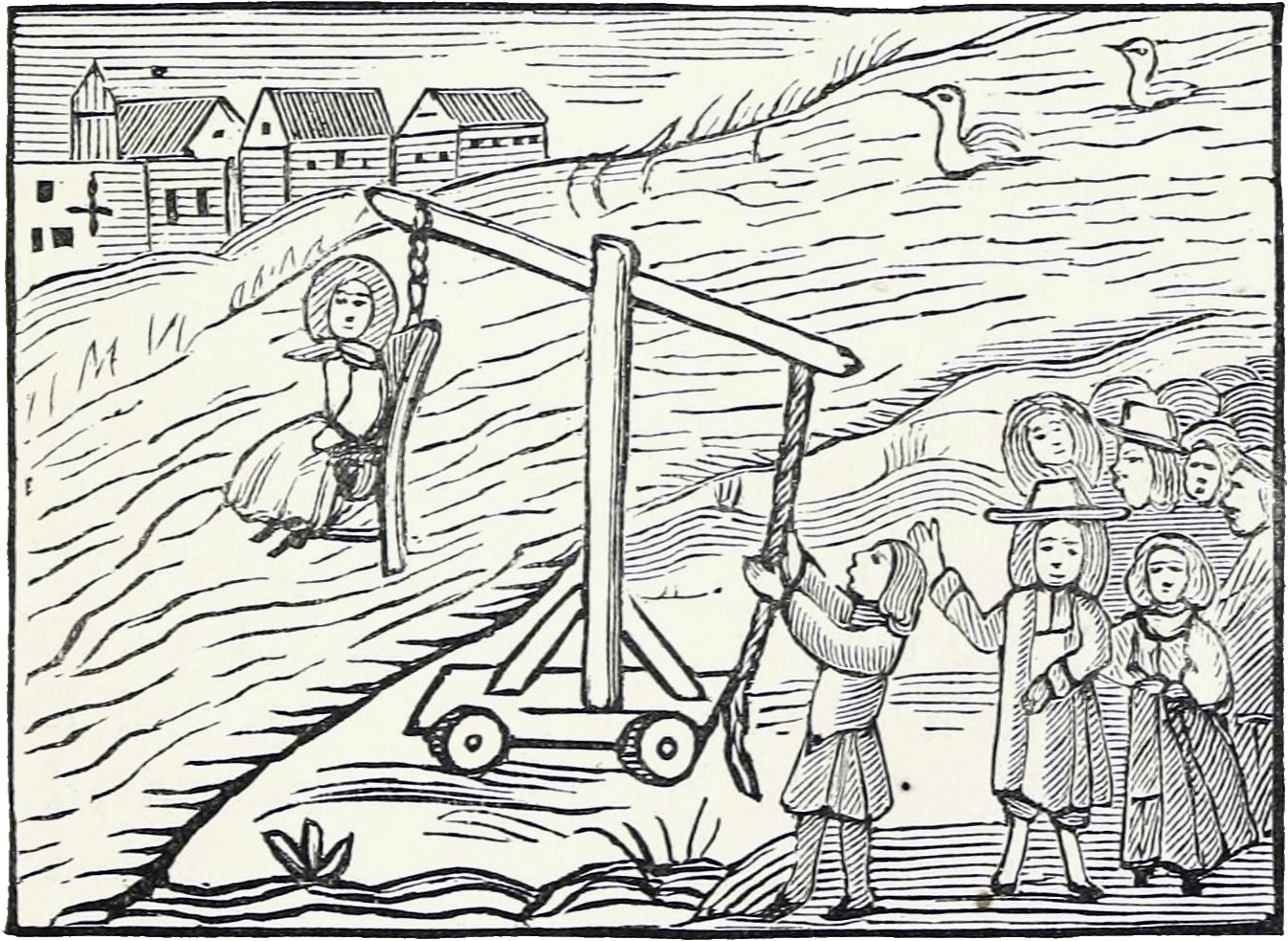

Punishing a woman accused of excessive arguing in the ducking stool, a form of water torture. Illustration from an 18th century chapbook reproduced in Chap-books of the eighteenth century by John Ashton, 1834. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Breaking on the wheel

A slow and torturous death where victims were tied to a large wooden wheel, left to die. The limbs of the victims were broken either before placing them on the wheel or during the process. Luther recommended this method for usurers and other criminals.

Illustration of execution by wheel, Switzerland, Lucerne picture chronicle, 1513. The victim’s limbs were broken and was then bound to the wheel, then left to die. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Variant of breaking on the wheel, using an iron rod to break the victim’s limbs. Detail of an etching from Les Misères et les malheurs de la guerre by Jacques Callot, Paris 1633. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Skeleton of a 25-30 year old man (16th to 18th century) who was broken on the wheel. The numerous broken bones are clearly visible and attest to the horrors of this inhumane torture method. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Beheading

Considered a more “merciful” execution, Luther called for this method for prostitutes, adulterers, and other moral offenders.

Depiction of the public execution of pirates (namely Klein Henszlein and his crew) in Hamburg, Germany, 10 September 1573. Leaflet news collection J. J. Wick (1560-1586). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Extermination and forced labor

Luther’s call for Jews to be sent into forced labor and to be expelled foreshadowed later historical atrocities against Jewish people, most notably during the Holocaust.

The Todesstiege (“Stairs of Death”) at the Mauthausen concentration camp quarry in Upper Austria (after 1940). Inmates were forced to carry heavy rocks up the stairs. In their severely weakened state, few prisoners could cope with this back-breaking labour for long. The Nazis used this method to exterminate prisoners (Jews, political dissidents, and others) through exhaustion – a method rooted in the forced labor Luther advocated. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Hanging

Commonly used for those deemed criminals under Lutheran-influenced authorities, including thieves and blasphemers. The method involved suspending the victim by the neck until death.

La Pendaison (The Hanging), a plate from French artist Jacques Callot’s 1633 series The Great Miseries of War. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sawing

A gruesome method of execution where the living victim was sawn or cut in half, either lengthwise or across the body, often used for particularly heinous crimes or as a form of public spectacle.

Illustration by Lucas Cranach the Elder, who produced many woodcuts for Luther’s writings, showing St. Simon sawn in two, ca. 1512. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The brutality of these methods, coupled with Luther’s theological justifications, reveals a troubling aspect of his legacy that contradicts the principles of mercy and compassion he claimed to uphold. His advocacy for such violence not only exposed a disturbing facet of his psyche but also set a precedent for religious intolerance and state-sanctioned persecution in the centuries that followed. By legitimizing extreme cruelty under the guise of divine authority, Luther’s rhetoric contributed to a culture of fear and violence that marred the Reformation era and its aftermath.

Theological justifications

Luther justified his calls for violence through his interpretation of scripture and his belief in the necessity of preserving divine order:

- The sword of secular authority: Luther believed that secular rulers were divinely appointed to maintain order and punish wrongdoing. In his view, rulers had both the right and the obligation to use violence against heretics, rebels, and other perceived threats to society.

- Divine judgment: Luther saw himself as an instrument of God’s will, which he believed necessitated harsh measures to root out sin and falsehood. He framed his calls for violence as acts of divine justice rather than personal vindictiveness.

- Social stability: In Luther’s mind, religious dissent and social rebellion threatened the cohesion of society. His advocacy for violence was rooted in a desire to protect the moral and spiritual integrity of the community, even at the cost of individual lives.

Conclusion

Martin Luther’s calls for violence against religious dissenters, heretics, and marginalized groups stand as one of the most troubling contradictions in his legacy. While he championed theological reform and individual faith, his endorsement of brutal punishments and executions reflects an unsettling willingness to use force to impose religious orthodoxy. His advocacy for violence, particularly against Anabaptists, Jews, and rival reformers, reveals a darker side to his reformist zeal — one that prioritized doctrinal purity over human dignity.

Luther’s belief in the divine mandate of secular rulers to punish dissenters highlights the intersection of religion and political power in the Reformation era. By legitimizing violence as a means of preserving divine order, he set a precedent that echoed through centuries of religious persecution. His words contributed to a culture in which faith was too often enforced through fear and coercion rather than persuasion and understanding.

The ethical contradictions within Luther’s legacy remain a critical subject of reflection. While his theological contributions reshaped Christianity, his advocacy for violence undermines the very principles of mercy and justice that he claimed to uphold. This paradox serves as a cautionary lesson on the dangers of dogmatic extremism, reminding us that any religious reform is always vulnerable to the corrupting influence of power and intolerance.

References and further reading

- Martin Luther, Von den Juden und ihren Lügen, 1543, Facsimile Publisher, 2016, ISBN: 978-9333628044

- Martin Luther, Tischreden, 1986, Reclam, ISBN: 978-3150012222

- Martin Luther, Wider die mörderischen und räuberischen Rotten der Bauern, 1525, available online at Bayerische Staatsbibliothekꜛ and on Zeno.orgꜛ (both in German)

- Martin Luther, Zur Frage, ob man auch als Soldat in einem Gott wohlgefälligen Stand lebt, 1526, available onlineꜛ in German

- Martin Luther, Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen, 2020, LIWI Literatur- und Wissenschaftsverlag, ISBN: 978-3965422575

- Martin Luther, Luthers Vorlesung Über Den Römerbrief, 1515/1516, 2018, Forgotten Books, ISBN: 978-0366360581

- Martin Luther, D. Martini Lutheri Exegetica Opera Latina, Vol. 2: Continens Enarrationes in Genesin Cap. X-XV, 2018, Forgotten Books, ISBN: 978-1390228441

- Martin Luther, Predigt über Exodus 22,18 (“Hexenpredigt”), 1526

- Martin Luther, Vom ehelichen Leben, 2023, Sharp Ink, ISBN: 978-8028345273

- Martin Luther, Johannes Ehmann, Confutation Alcorani, 1542, Würzburg: Echter, 1999, ISBN: 3893751777

- Martin Luther, Eine Heerpredigt wider den Türken, 2010, Verlag Classic Edition, ISBN: 978-3839703168

- Günter: Fabiunke, Martin Luther als Nationalökonom. Anhang: Martin Luther, An die Pfarrherrn wider den Wucher zu predigen, Vermahnung, 1540, 1963, Berlin. Akademie-Verlag

- Martin Luther, Brief an Philipp Melanchthon vom 1.8.1521

- Martin Luther, Ernste Vermahn- und Warnschrift Luthers an die Studenten zu Wittenberg, am 13.5.1543 öffentlich an der Kirche angeschlagen, 1543

- Martin Luther, Wider den falsch genannten geistlichen Stand des Papstes und der Bischöfe, 1522

- Martin Luther, Zwo harte ernstliche Schriften. Doct. Martini an den Christlichen Leser, 1518

- Martin Luther, Der 82. Psalm durch D.M.L. geschrieben und ausgelegt, 1530

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 9 -Mitte des 16. bis Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vom Völkermord in der Neuen Welt bis zum Beginn der Aufklärung, 2010, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499624438

comments