The genocide in South America and the role of the Catholic Church

The colonization of South America by European powers in the 15th and 16th centuries marked one of the darkest chapters in human history. Under the guise of spreading Christianity, European conquerors and missionaries orchestrated a devastating conquest that annihilated entire cultures, subjugated indigenous populations, and caused the deaths of millions. The Spanish and Portuguese empires, often with the active support and encouragement of the Catholic Church, framed this colonization as both a civilizing mission and a divine mandate. However, the resulting destruction starkly contradicts Christian core teachings, which emphasize love, humility, and compassion. The genocide in South America, as some historians have termed it, was not merely the product of imperial greed but also of religious dogma weaponized to legitimize conquest and violence.

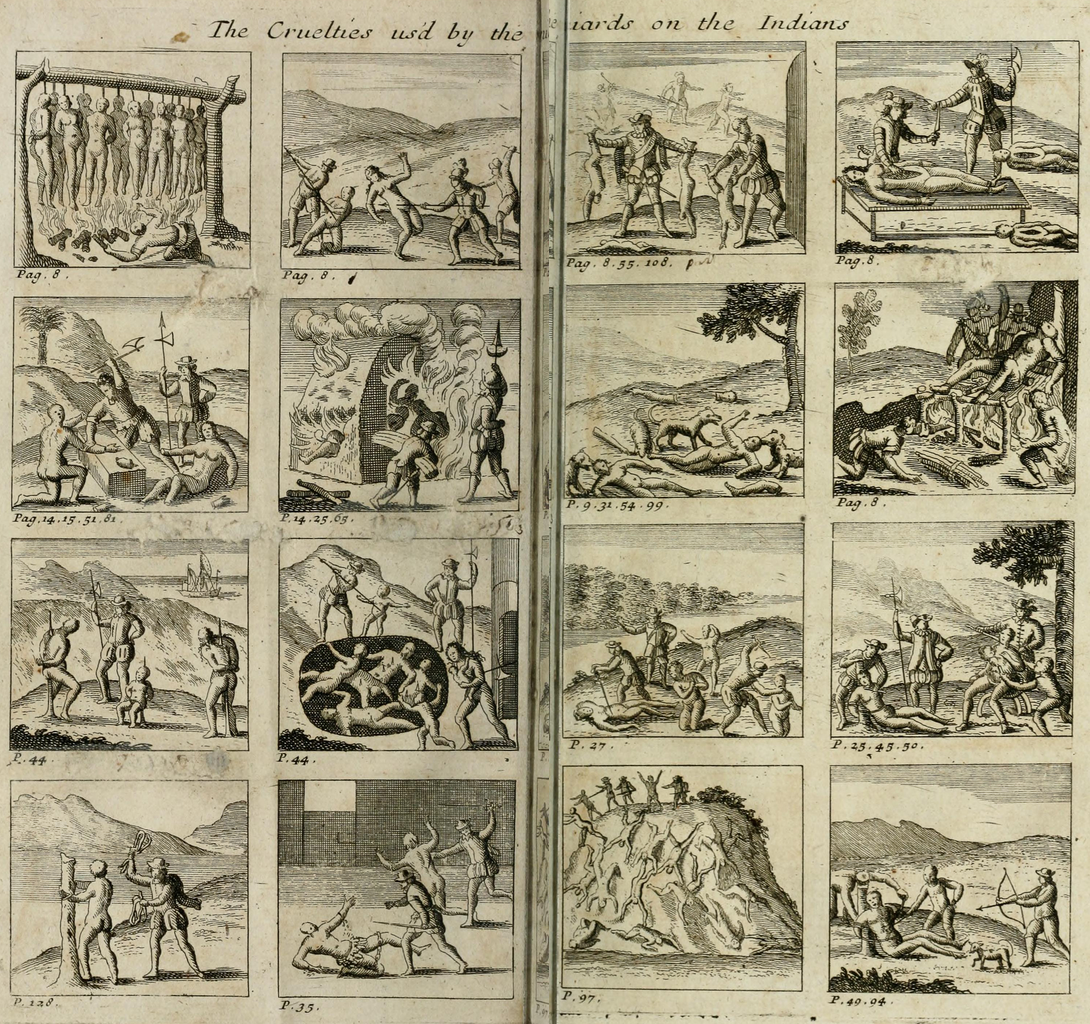

A 1598 engraving by Theodor de Bry depicting a Spaniard feeding slain Indigenous American women and children to his dogs. De Bry’s works are characteristic of anti-Spanish propaganda which resulted from the Eighty Years’ War. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The arrival of Europeans and the conquest of South America

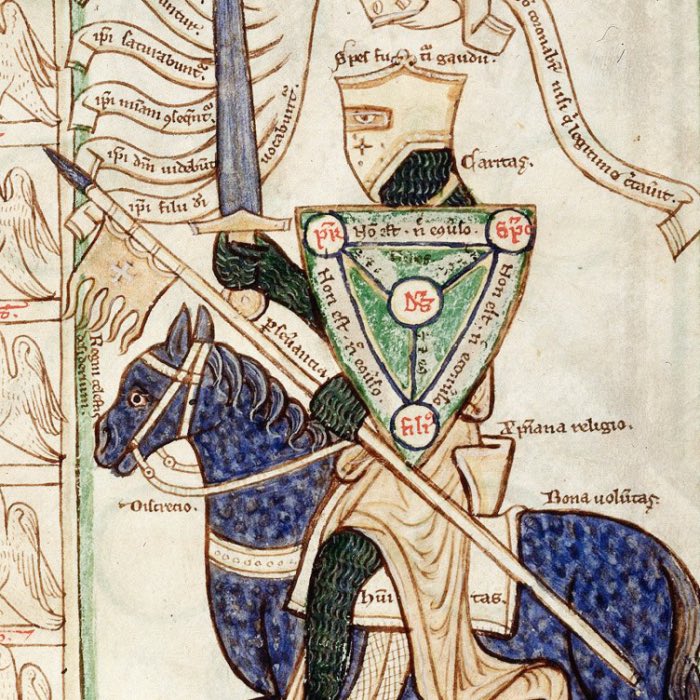

In 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Spain and Portugal, granting them vast swathes of South America. This treaty, ratified by Pope Alexander VI, symbolized the Church’s early involvement in the colonization process. The papal bulls Dum Diversas (1452) and Inter Caetera (1493) granted European monarchs the right to conquer and enslave non-Christian peoples, framing colonization as a divinely sanctioned endeavor.

Battle of the militia of Mogi das Cruzes and the Botocudos, by Oscar Pereira da Silva, 1920. The Botocudos were a group of indigenous peoples who resisted Portuguese colonization in Brazil. During the Portuguese colonization of the Americas, Cabral made landfall off the Atlantic coast. Over the following decade the indigenous Tupí, Tapuya, Caeté, Goitacá and other tribes which lived along the coast suffered large depopulation due to disease and violence. It is estimated that of the 2.5 million indigenous peoples who had lived in the region which now comprises Brazil, less than 10 percent survived to the 1600s. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

When Spanish conquistadors, such as Francisco Pizarro and Hernán Cortés, arrived in South America, they encountered highly developed civilizations, including the Inca Empire. Driven by the quest for gold and the desire to expand their empires, the Europeans unleashed brutal campaigns of conquest. Indigenous resistance was met with overwhelming violence, including massacres, enslavement, and the destruction of cultural and religious institutions.

Another illustration of Spanish atrocities by Theodor de Bry, 1664, showing the hanging, burning and clubbing of Indians by Spanish soldiers. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

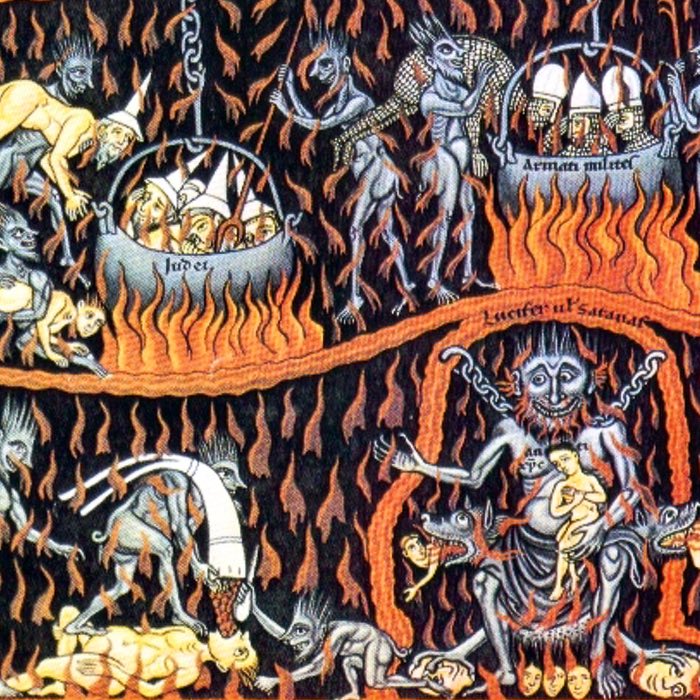

The justification for these atrocities was often couched in Christian terms. Indigenous peoples were labeled “savages” and “pagans”, their spiritual practices dismissed as idolatry. The conquistadors framed their violence as a necessary step in bringing salvation to these “heathens”, turning mass murder into a perverse form of missionary work.

The role of Christian missionaries

The Catholic Church played a dual role in the colonization of South America. On the one hand, missionaries such as the Jesuits, Franciscans, and Dominicans sought to convert indigenous peoples to Christianity. They established missions, or reducciones, where indigenous populations were resettled, ostensibly to protect them from exploitation by the colonizers. In these missions, the indigenous peoples were taught Christian doctrine, European farming techniques, and crafts.

While some missionaries genuinely sought to improve the lives of indigenous peoples, the overall impact of this mission work was devastating. Indigenous spiritual traditions were systematically eradicated, with temples destroyed, sacred objects desecrated, and rituals banned. The forced conversion to Christianity often involved coercion, violence, and the use of fear, including threats of eternal damnation.

One of the most egregious examples of religious coercion was the requirement that indigenous peoples accept baptism, often without understanding its significance. In many cases, refusal to convert was met with severe punishment, including execution. Indigenous leaders and shamans were particularly targeted, as their influence posed a threat to the missionaries’ efforts to establish Christian dominance.

The curial legitimation of violence

The Catholic Church not only sanctioned the conquest but also provided theological justification for the subjugation and exploitation of indigenous peoples. The Requerimiento, a declaration read aloud by Spanish conquistadors, exemplifies this complicity. Written in 1513 by Spanish jurist Juan López de Palacios Rubios, the Requerimiento was a legal and theological document that demanded indigenous peoples submit to Spanish rule and accept Christianity. If they refused, the conquistadors claimed divine justification to wage war, enslave them, and seize their lands.

This document, often read in Spanish to indigenous peoples who did not understand the language, symbolized the cynical use of religion to legitimize conquest. It encapsulated the deep contradiction between the Church’s professed values and its actions in South America.

The cruelties used by the Spaniards on the Indians, from A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies by Bartolomé de las Casas, 1552. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Moreover, the Church benefited materially from the colonization. The wealth extracted from South America, including gold, silver, and other resources, often flowed directly to the Church. The construction of lavish cathedrals in Europe was financed, in part, by the plunder of indigenous lands. The Church’s hierarchy, far from opposing the conquest, actively profited from it.

Depiction of Spanish treatment of the indigenous populations in the Caribbean by Theodore de Bry, illustrating Spanish Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas’s indictment of early Spanish cruelty, known as the Black legend, and indigenous barbarity, including human cannibalism, in an attempt to justify their enslavement, 1550 Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The human cost: Genocide and cultural annihilation

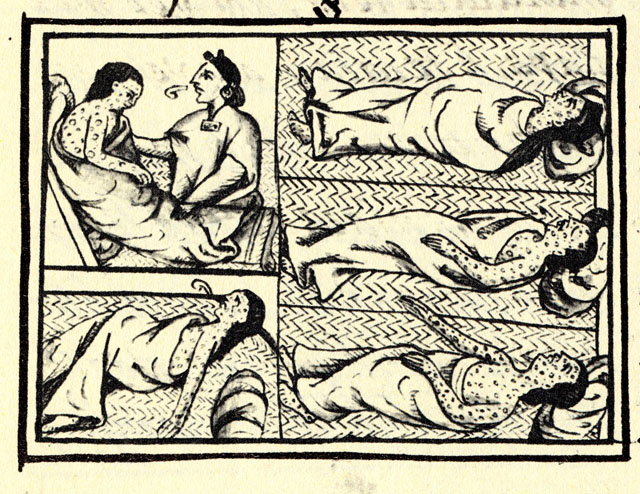

The consequences of the Christian conquest of South America were catastrophic. The indigenous population such as the Inca, Aztec, and Maya, estimated at over 50 million before the arrival of Europeans, was decimated by violence, enslavement, and disease. Smallpox, measles, and other diseases introduced by Europeans wiped out entire communities, exacerbating the devastation caused by war and forced labor.

Drawing accompanying text in Book XII of the 16th-century Florentine Codex (compiled 1540–1585), showing a Nahua suffering from smallpox. The Nahua were one of the indigenous peoples of Mexico. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The cultural impact was equally profound. Indigenous languages, traditions, and knowledge systems were suppressed, with many lost forever. The destruction of religious sites and the imposition of Christianity severed indigenous peoples from their spiritual heritage. This cultural genocide was framed as a necessary step in bringing “civilization” to South America, further highlighting the moral hypocrisy of the colonizers and their religious backers.

Theological and moral contradictions

The actions of the Catholic Church in South America represent a stark betrayal of Christianity’s self-proclaimed core values. The Gospel emphasizes love for one’s neighbor, the protection of the vulnerable, and the rejection of greed and violence. Yet the Church’s complicity in the conquest was driven by precisely the values Jesus condemned: the pursuit of wealth, power, and domination.

The forced conversion of indigenous peoples contradicts the principle of free will, a cornerstone of Christian theology. Jesus’ message was one of invitation, not coercion. By imposing Christianity through violence and intimidation, the Catholic Church undermined the very faith it sought to spread.

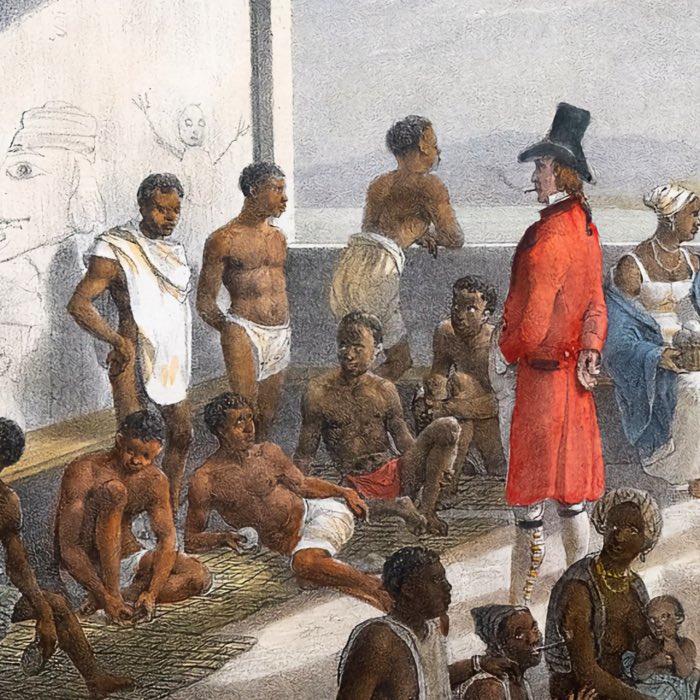

A scene below deck of a slave ship headed to Brazil, painting by the German artist Johann Moritz Rugendas, c. 1830. Rugendas had been an eyewitness to the scene. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Moreover, the Church’s support for slavery and exploitation stands in direct opposition to the Christian call to love and serve others. The reduction of indigenous peoples to mere resources for economic gain reflects a profound moral failure, one that continues to stain the legacy of Christianity.

Transatlantic slave trade between the triangular Europe, Africa, and the Americas. From Africa, slaves were shipped to the Americas, where they were sold. The ships then returned to Europe with goods such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton. On their way back to Africa, the ships transported goods such as textiles, rum, and manufactured goods. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Painting of the Marie Séraphique upon arrival at a port in Saint-Domingue, Haiti (top), in 1773, by Jean-René L’Hermite, and view of the ship’s slave deck (bottom). The latter illustrates how slaves were transported in inhumane conditions within the African slave trade to the Americas. Source top: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain), source bottom: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Overall, the actions and measures taken by the Catholic reflect the longer trend of the Church’s involvement in politics and power struggles, often at the expense of its spiritual and moral integrity. The conquest of South America was not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of collusion between the Church and secular authorities, leading to the corruption of both institutions, which marked the era of the Renaissance Church.

A plan of the British slave ship Brookes, showing how 454 slaves were accommodated on board after the Slave Trade Act 1788. This same ship had reportedly carried as many as 609 slaves and was 267 tons burden, making 2.3 slaves per ton. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Resistance and resilience

Despite the overwhelming violence and oppression, indigenous peoples in South America resisted colonization in various ways. Some communities rebelled against the conquistadors, while others preserved their traditions in secret, blending them with Christian practices to create syncretic forms of worship. This resilience highlights the enduring strength of indigenous cultures, even in the face of immense suffering.

The Natives of Cumaná attack the mission after Gonzalo de Ocampo’s slaving raid (1515). Colored copperplate by Theodor de Bry, published in the Relación brevissima de la destruccion de las Indias, 1631. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, a Spanish Dominican friar, also emerged as vocal critics of the conquest. Las Casas condemned the brutality of the colonizers and advocated for the rights of indigenous peoples, offering a rare voice of dissent within the Church. While his efforts were ultimately limited, they underscore the existence of moral opposition to the atrocities committed in the name of Christianity.

Bust of Hatuey, who rebelled against the Spanish. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Conclusion

The Christian genocide in South America stands as a stark reminder of the moral contradictions and failures of the Catholic Church during the colonial period. While the conquest was framed as a civilizing mission and an act of evangelization, it resulted in genocide, cultural annihilation, and the betrayal of Christian core teachings. The Church’s complicity in these atrocities reveals how religion can be weaponized to justify violence and oppression, highlighting the dangers of institutional power divorced from moral accountability.

The Christian genocide in South America stands as a stark reminder of the moral contradictions and failures of the Catholic Church during the colonial period. While the conquest was framed as a civilizing mission and an act of evangelization, it resulted in genocide, cultural annihilation, and the betrayal of self-proclaimed Christian core values. The Church’s complicity in these atrocities reveals how religion can be weaponized to justify violence and oppression, highlighting the dangers of institutional power divorced from moral accountability.

However, the impact of colonization did not end with military conquest and forced conversion. Indigenous resistance persisted in various forms, from armed uprisings to the preservation of cultural and spiritual traditions in secrecy. Figures such as Tupac Amaru in the Andes and the Mapuche resistance in Chile challenged colonial domination, demonstrating the resilience of indigenous identities despite relentless persecution.

In modern times, the Catholic Church has taken steps to acknowledge its role in colonization, though often in ambiguous or symbolic ways. Pope John Paul II and Pope Francis have both addressed the suffering of indigenous peoples, with Francis apologizing for the Church’s complicity in colonial abuses. However, these acknowledgments fall short of substantive restitution, leaving unresolved questions about historical justice and reparations.

Ultimately, the Church’s role in the colonization of South America underscores a broader pattern of religious institutions entangling themselves with imperial power structures. This historical episode serves as a warning about the consequences of unchallenged religious authority and the necessity of holding such institutions accountable for their past and present actions. The legacy of colonial violence lingers in the continued marginalization of indigenous communities, raising pressing moral and ethical questions that remain unanswered today.

References and further reading

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 9 -Mitte des 16. bis Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vom Völkermord in der Neuen Welt bis zum Beginn der Aufklärung, 2010, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499624438

- Bartolomé de las Casas, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, 2016, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1539797722

- Todorov, Tzvetan, The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other, 1999, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN: 9780806131375.

- Hemming, John, The Conquest of the Incas, 1970, Mariner Books, ISBN: 978-0806131375

- Pagden, Anthony, The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology, 1987, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521337045

- Hulme, Peter, Colonial Encounters: Europe and the Native Caribbean, 1492-1797, 1992, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415011464

- Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia, Oppressed But Not Defeated: Peasant Struggles Among the Aymara and Qhechwa in Bolivia, 1900-1980, 1987, UNRISDꜛ

- Stannard, David E., American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World, 1993, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195085570

- Blackburn, Carole, Harvest of Souls: The Jesuit Missions and Colonialism in North America, 1632–1650, 2000, McGill-Queen’s University Press, ISBN: 978-0773520479

comments