The Black Holocaust and the complicity of the Catholic Church

The Black Holocaust, often referred to as Maafa (a Swahili term meaning “great disaster”), represents one of the most prolonged and devastating human atrocities in history. It encompasses the mass enslavement, exploitation, and extermination of African people, particularly through the Trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Atlantic slave trades. This prolonged system of oppression did not end with slavery’s formal abolition but continued through colonialism, imperialism, systemic racism, and the economic disenfranchisement of African and African-descendant populations worldwide.

Public punishment in Santa Ana Square, Brazil, Johann Moritz Rugendas, lithograph, after 1827, before 1835. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Central to this system was the role of the Catholic Church, which not only provided theological justification for the enslavement of Africans but also materially benefitted from it. Papal decrees facilitated European expansion and the trade of enslaved persons, while Church institutions engaged in and profited from slavery. Even after abolition, the Church was slow to confront its moral culpability, and its complicity remains a subject of historical reckoning.

The dimensions of the Black Holocaust

The Black Holocaust, or Maafa, spans multiple regions and centuries, encompassing various forms of enslavement and exploitation imposed upon African populations. These include the Trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Atlantic slave trades, all of which had devastating consequences for African societies.

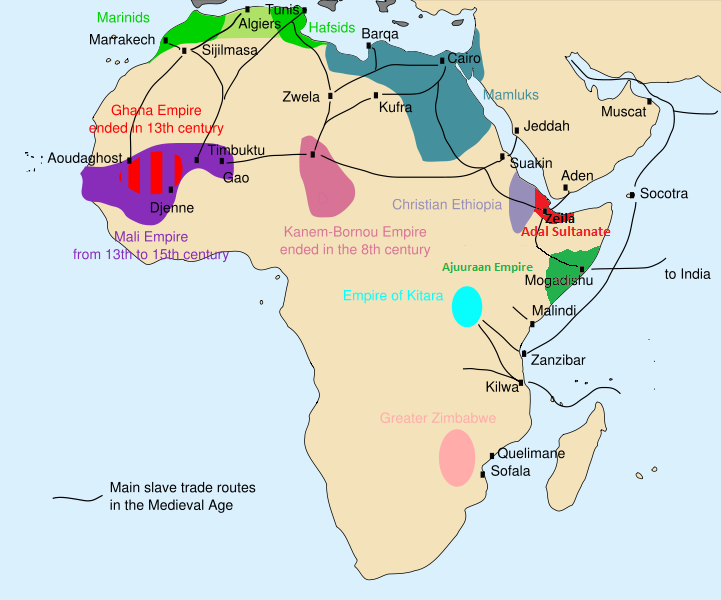

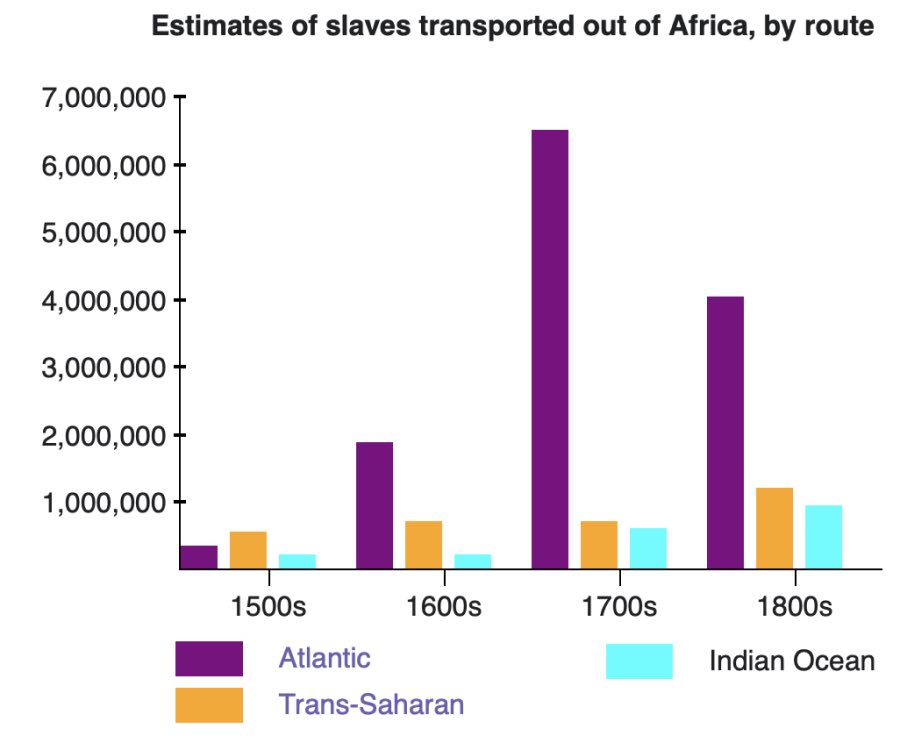

Slave trade out of Africa, 1500–1900. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The origins and scope of Maafa

The enslavement of Africans was not limited to the transatlantic trade but was part of a broader global system of forced labor and human trafficking. Each major trade route had its distinct patterns and participants:

- The Trans-Saharan slave trade – Conducted primarily by Arab and Berber traders, this trade route transported African captives into North Africa and the Middle East. Many were forced into domestic servitude, military service, or concubinage.

- The Indian Ocean slave trade – African slaves were taken to the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia, where they were used as laborers, concubines, and soldiers. This trade persisted for centuries, well beyond the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade.

- The Red Sea slave trade – Focused on East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, this trade saw African captives subjected to forced labor and social marginalization in predominantly Islamic regions.

- The Atlantic slave trade – European colonial powers, including Portugal, Spain, Britain, France, and the Netherlands, enslaved millions of Africans and transported them to the Americas. This trade fueled the economies of European empires and devastated African populations.

The main slave routes in medieval Africa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Estimates of slaves transported out of Africa, by route. Based on Saleh & Wahby (2022)ꜛ. Source: Wikipediaꜛ (license: public domain)

The impact of the slave trades on Africa

The long-term effects of the Black Holocaust on African societies were catastrophic. The large-scale removal of people disrupted African communities, economies, and governance structures. The loss of millions of people, particularly young and able-bodied individuals, severely weakened African societies and economies. The demand for captives fueled warfare between African groups, creating a cycle of violence that hindered long-term economic development. Traditional African leadership systems were often undermined or destroyed, leading to increased European control and later colonization. This destruction of African governance further facilitated European imperial expansion, as many African states became unable to resist foreign domination effectively.

Transatlantic slave trade between the triangular Europe, Africa, and the Americas. From Africa, slaves were shipped to the Americas, where they were sold. The ships then returned to Europe with goods such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton. On their way back to Africa, the ships transported goods such as textiles, rum, and manufactured goods. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The role of European and Arab powers

Both European and Arab traders played central roles in sustaining and expanding the African slave trade. European colonial empires, particularly Portugal, Spain, Britain, France, and the Netherlands, aggressively pursued the transatlantic trade, using enslaved labor to build their overseas economies. This exploitation was not limited to plantation economies but also extended into the construction of infrastructure, urban development, and industrial production.

A slave market in Brazil, showing men, women and children being sold. Some are cooking food over an open fire, Johann Moritz Rugendas (?). Rugendas arrived in Brazil in 1822, hired as an illustrator for Baron von Langsdorff’s scientific expedition. Rugendas remained on his own in Brazil until 1825, exploring and recording his many impressions of daily life in the provinces of Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, and quickly the coastal provinces of Bahia and Pernambuco on his journey back to Europe. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Complicit countries: Slaves embarked to America from 1450 until 1866 by country. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

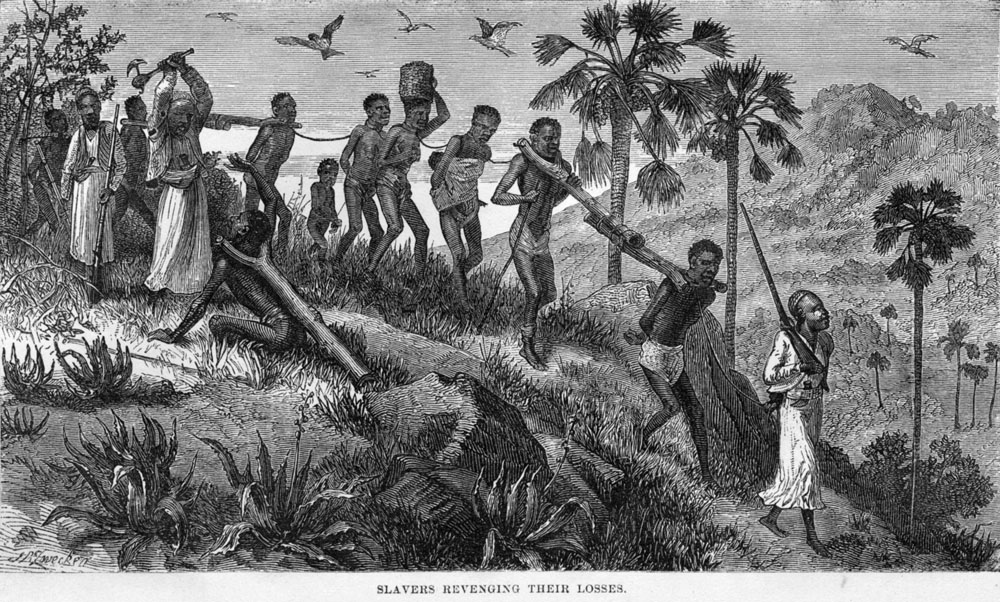

Meanwhile, the Arab slave trade predated European involvement and continued long after the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade. Enslaved Africans were frequently used in the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia, often working in domestic servitude, agriculture, and military service. The persistence of this trade underscores the global reach of African enslavement and the extensive complicity of different political and religious entities in maintaining systems of forced labor.

Arab-Swahili slave traders and their captives along the Ruvuma River in Mozambique. Captioned, “Slavers Revenging their Losses”, shows a coffle of men, women, and children, led by Arab slavers; one of the guards is murdering a captive unable to keep up with the rest. These people were taken across Central Africa to the east coast of Africa. The engravings in this book are based on, according to the editor, “rude sketches” made by Livingstone. On June 19, 1866, Livingstone wrote: “We passed a woman tied by the neck to a tree and dead, the people of the country explained that she had been unable to keep up with the other slaves in a gang, and her master had determined that she should not become the property of anyone else if she recovered after resting a time. … we saw others tied up in a similar manner … the Arab who owned these victims was enraged at losing his money by the slaves becoming unable to march, and vented his spleen by murdering them”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The slave market in Zanzibar, Émile Bayard, c. 1860. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The lingering effects of Maafa

Even after the formal abolition of slavery, the structural legacies of Maafa continued to shape global racial and economic hierarchies. Former colonial powers imposed economic and political systems that perpetuated African dependency and exploitation, ensuring that African nations remained economically subordinate to their former colonial rulers. Structural racism and economic disparities persist among African and African-descendant populations, with wealth gaps and limited access to opportunities rooted in centuries of forced labor and dispossession. Additionally, racial oppression, segregation, and disenfranchisement continue to affect African-descendant communities in the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe. Systemic discrimination, racial violence, and barriers to political participation remain significant challenges that trace their origins to the enslavement and exploitation of African peoples.

Burning of a village in Africa and capture of its inhabitants, 1859. To escape slave raids some Africans escaped into swamp regions or to other areas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

African opposition to the slave trade: On July 1, 1839, enslaved Mende people aboard the Amistad revolted and took control of the ship. Color Engraving and Frontispiece from John Warner Barber, A History of the Amistad Captives, 1840. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The role of the Catholic Church in legitimizing the enslavement of Africans

The Catholic Church, as the most powerful religious institution in medieval and early modern Europe, played a decisive role in shaping attitudes toward slavery. Unlike early Christian communities, which were diverse in their perspectives on slavery, the medieval Church aligned itself with state powers and economic interests that relied on forced labor. This alignment became particularly evident with the rise of European exploration and expansion.

Portrait of Pope Nicholas V (r. 1447-1455), Peter Paul Rubens, 1612-1616. Nicholas V issued the papal bull Dum Diversas in 1452, authorizing the Portuguese to enslave non-Christian peoples. In 1455, he issued the bull Romanus Pontifex, granting Portugal exclusive rights to trade and conquer in Africa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Papal bulls issued in the 15th century explicitly sanctioned the conquest of non-Christian territories and the enslavement of their populations. Pope Nicholas V’s Dum Diversas (1452) granted King Afonso V of Portugal the authority to enslave “Saracens, pagans, and any other unbelievers”. This decree was reaffirmed in Romanus Pontifex (1455), which expanded on this initial authorization by granting Portugal exclusive rights to trade and conquer in Africa, thereby embedding slavery into the emerging global economy. These decrees not only provided religious justification for the forced subjugation of Africans but also directly facilitated the development of the transatlantic slave trade, as Portuguese ships began systematically capturing and selling enslaved people.

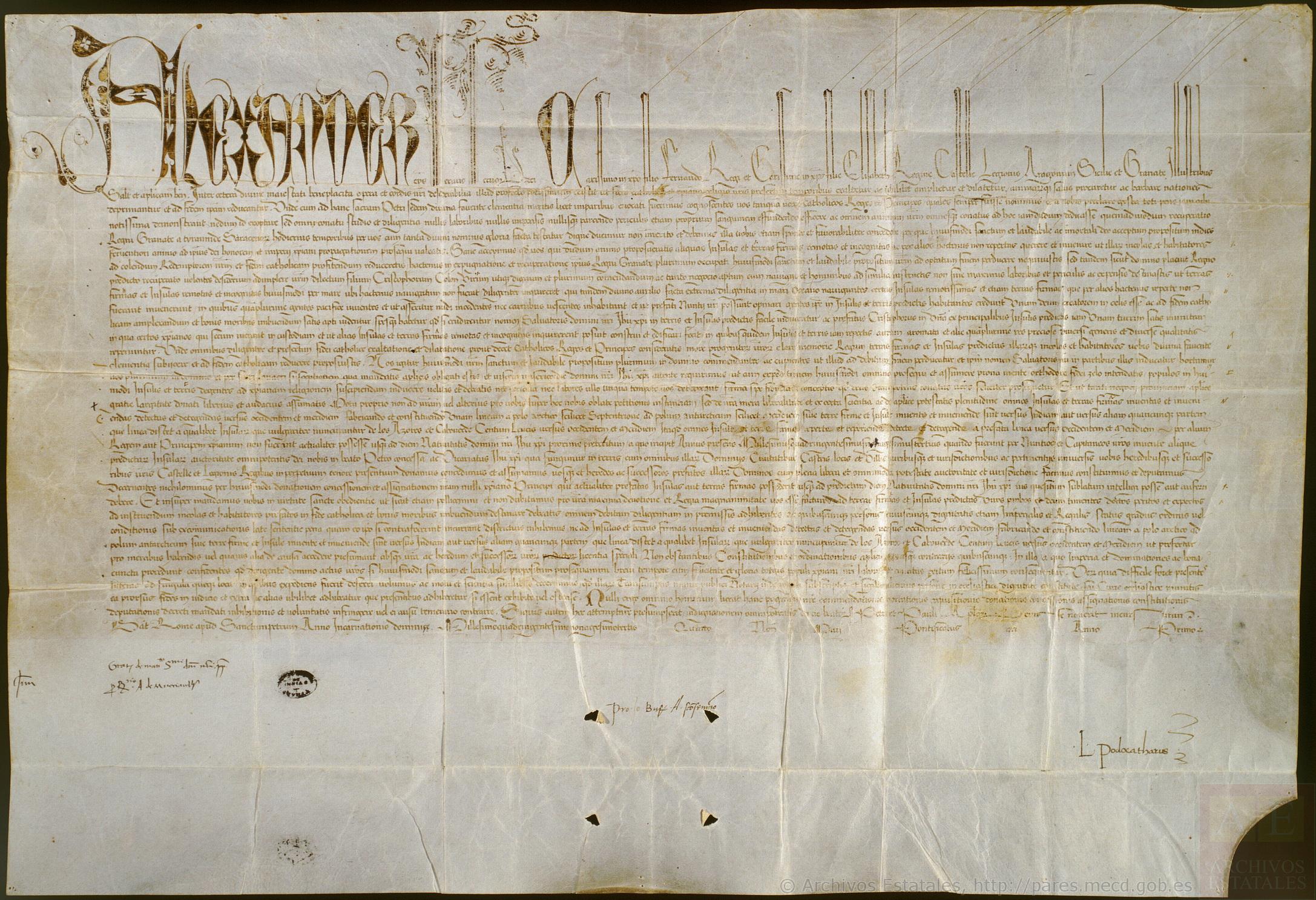

Inter caetera document dated May 4, 1493 in the Archivo General de Simancas. This papal bull by Pope Alexander VI divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Spain and Portugal along a meridian 100 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

When Spain and Portugal expanded their colonial empires, papal approval reinforced the ideological foundation of African enslavement. The 1493 bull Inter Caetera by Pope Alexander VI played a crucial role in formalizing colonial domination by dividing newly “discovered” lands between Spain and Portugal. This document effectively legitimized the seizure of indigenous territories and the subjugation of non-Christian peoples under European rule. While framed as a means of spreading Christianity, these decrees became instruments of imperial conquest, paving the way for centuries of brutal exploitation, land dispossession, and racialized slavery. The Church’s endorsement of these practices solidified a structure in which European monarchs and religious institutions profited from human trafficking on an unprecedented scale.

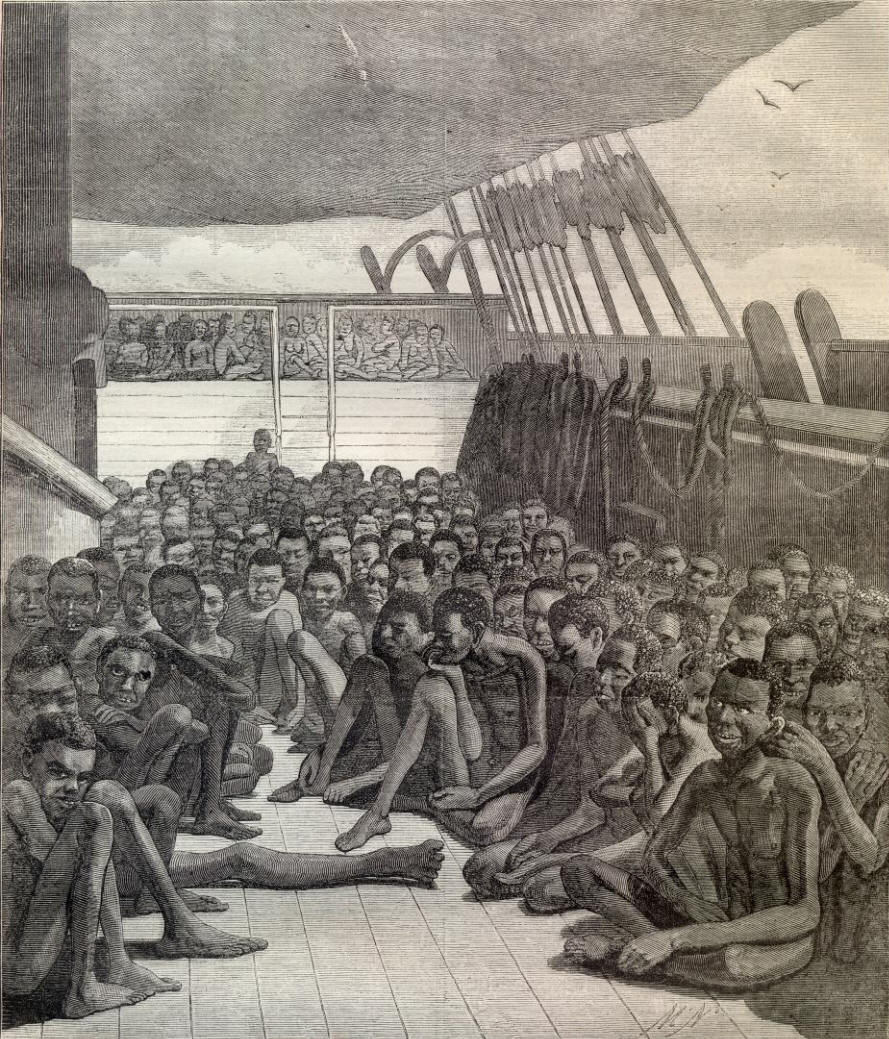

A wood engraving after a daguerreotype of slaves on the captured slave-ship, Wildfire, brought to Key West in 1860 from Harper’s Weekly. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Church as a beneficiary of the transatlantic slave trade

Beyond legitimizing the slave trade, the Catholic Church directly profited from it. Religious orders such as the Jesuits, Franciscans, and Dominicans owned and operated plantations in the Americas, using enslaved African labor to generate wealth. Jesuit missions in Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America were particularly notable for their extensive use of enslaved people. Enslaved Africans not only worked on plantations but also built churches, monasteries, and other religious institutions that remain standing today.

Painting of the Marie Séraphique upon arrival at a port in Saint-Domingue, Haiti (top), in 1773, by Jean-René L’Hermite, and view of the ship’s slave deck (bottom). The latter illustrates how slaves were transported in inhumane conditions within the African slave trade to the Americas. Source top: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain), source bottom: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Church’s financial entanglement in slavery extended beyond plantations. Ecclesiastical institutions received tithes and donations derived from the profits of slavery. Bishops and clergy often acted as intermediaries in the trade, blessing ships and overseeing the religious conversion of enslaved Africans, a process that did not include granting them freedom but instead sought to reconcile their subjugation with Christian doctrine.

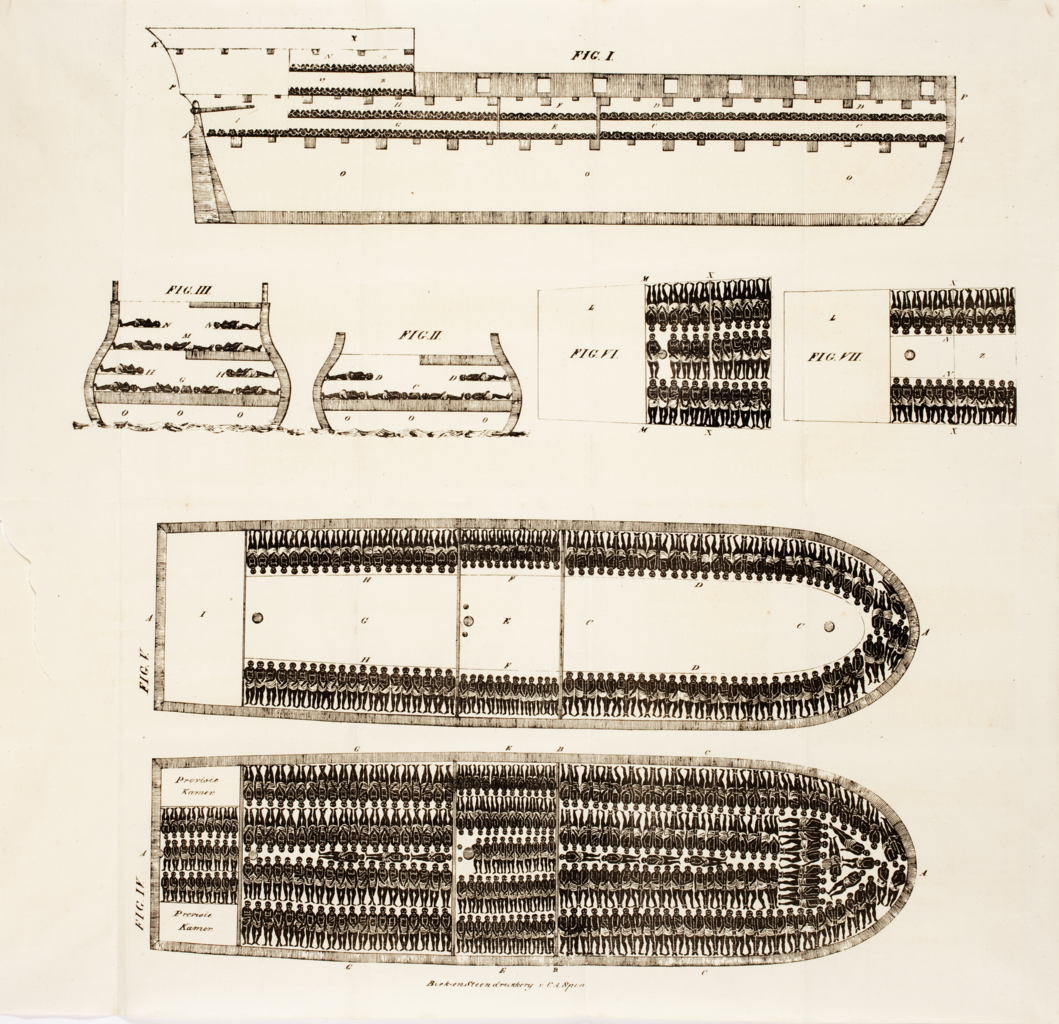

Diagram of a large slave ship, showing the Storing slaves on a trans-Atlantic transport ship with four slave decks, from Thomas Clarkson’s The cries of Africa to the inhabitants of Europe, c. 1822. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Moreover, Catholic doctrines and practices reinforced the racial hierarchy that underpinned slavery. Baptized Africans were not freed from servitude but were instead placed within a paternalistic framework in which the Church saw itself as a guardian of their souls while denying them their basic human rights. The moral contradictions inherent in this system went largely unchallenged by Church authorities.

A scene below deck of a slave ship headed to Brazil, painting by the German artist Johann Moritz Rugendas, c. 1830. Rugendas had been an eyewitness to the scene. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Theological contradictions and moral failures

The Church’s role in slavery highlights profound theological contradictions. Christianity, at its core, espouses the principles of love, dignity, and justice. Yet, for centuries, Catholic authorities defended slavery as part of a divinely sanctioned order. The doctrine of Just War, which allowed for the enslavement of non-Christians defeated in battle, was adapted to justify the perpetual servitude of Africans, who were deemed inferior and in need of Christian guidance.

Enslaved people inside a sugar boiling house on the island of Antigua, William Clark, 1823. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 1.0)

The idea that slavery could coexist with Christian morality was widely accepted by Catholic theologians well into the 19th century. Even when Pope Paul III issued Sublimis Deus (1537), which declared that Indigenous peoples had souls and should not be enslaved, it made no such clear statement regarding Africans. The selective application of moral arguments underscored the Church’s prioritization of European imperial and economic interests over universal Christian ethics.

Enslaved people working on a coffee plantation in Brazil, c. 1882. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Even when abolitionist movements gained traction, the Church remained ambivalent. While some Catholic leaders, particularly in Latin America, spoke out against slavery, the Vatican as an institution was slow to act. It was not until Pope Gregory XVI’s In Supremo Apostolatus (1839) that the Church explicitly condemned the slave trade. However, this condemnation did not translate into immediate action, as Catholic nations, including Spain and Portugal, continued their involvement in slavery for decades.

Punishing slaves at Calabouco, in Rio de Janeiro, Augustus Earle, c. 1822. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The legacy of the Catholic Church’s complicity

The consequences of the Church’s complicity in slavery did not end with abolition. Colonialism, another system of economic and racial subjugation, was deeply intertwined with Catholic missions. Many of the same ideological frameworks used to justify slavery were repurposed to legitimize European control over Africa and its people. Catholic schools and missionary efforts often served as tools of cultural erasure, replacing indigenous African traditions with European customs under the pretense of Christianization.

A slave being inspected. Engraving by Whitney, Jocelyn & Annin, after Frank Blackwell Mayer, was originally published in Captain Canot, or Twenty Years of an African Slaver by Brantz Mayer. It depicts an African man being inspected by a white man while another white man talks with slave traders. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Church’s reluctance to fully acknowledge its historical role in slavery remains a contentious issue. While modern popes, including John Paul II and Francis, have expressed regret over the suffering inflicted by the transatlantic slave trade, these statements have been largely symbolic. There has been no formal institutional reckoning, no financial restitution, and little effort to address the systemic inequalities that persist as a result of slavery and colonialism.

Major slave trading regions of Africa, 15th–19th centuries, nspired by Benjamin, Thomas, The Atlantic World: Europeans, Africans, Indians, and their Shared History, 1400-1900, 2009, Cambridge University Press. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The lasting impact of the Black Holocaust is evident in the economic and social disparities that continue to affect African and African-descendant populations. Structural racism, economic disenfranchisement, and the marginalization of African heritage remain global issues. The Catholic Church, as a historically significant participant in these injustices, bears a moral responsibility to engage in meaningful reparative action, beyond mere words of apology.

Bunce Island in Sierra Leone exported tens of thousands of Africans to the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia. Gadsden’s Wharf in Charleston, South Carolina, received the majority of imported slaves from Bunce Island. African Americans in the Sea Islands can trace their ancestry to Sierra Leone. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Conclusion

The Black Holocaust is not just a historical event but an ongoing reality, deeply embedded in the structures of modern society. The Catholic Church played a critical role in legitimizing, enabling, and profiting from the enslavement of Africans, and its complicity extended beyond the slave trade into the colonial era and beyond. The theological contradictions and moral failures that allowed this to happen remain unresolved, as the Church has yet to take substantive steps toward reparative justice.

This dark chapter of history casts a long shadow over the Church’s moral authority and its professed commitment to justice. In light of these atrocities, its credibility is irreparably called into question. Can an institution that was complicit in the systematic dehumanization of millions still claim to be a beacon of morality? I think not. While it has traditionally presented itself as the moral and theological compass of Christian civilization, its direct engagement in slavery, colonial expansion, and systemic oppression calls this identity into question. The Church did not function as a purely religious institution concerned with salvation — it was a political force entangled in territorial expansion, economic exploitation, and racial subjugation. From the Renaissance popes to the colonial era, it wielded its influence to sanctify violence and justify systemic oppression, prioritizing power and wealth over the very values it claimed to uphold. The Black Holocaust exemplifies this betrayal, exposing a history of complicity that cannot be excused as an unfortunate misstep but rather as a deliberate strategy to maintain dominance. This history serves as a stark reminder that the Catholic Church’s moral authority is not inherent or absolute; rather, it is eroded by its own historical actions. Christianity’s claims to moral leadership are forever tainted by its complicity in oppression.

Despite public acknowledgments of past wrongs by various Church leaders, meaningful action to address historical injustices remains absent. The systemic exploitation of African labor, culture, and resources under the guise of religious duty continues to shape modern socio-economic disparities. Reparations — whether through financial compensation, institutional reform, or direct investment in African and African-descendant communities — have yet to be seriously considered at an institutional level.

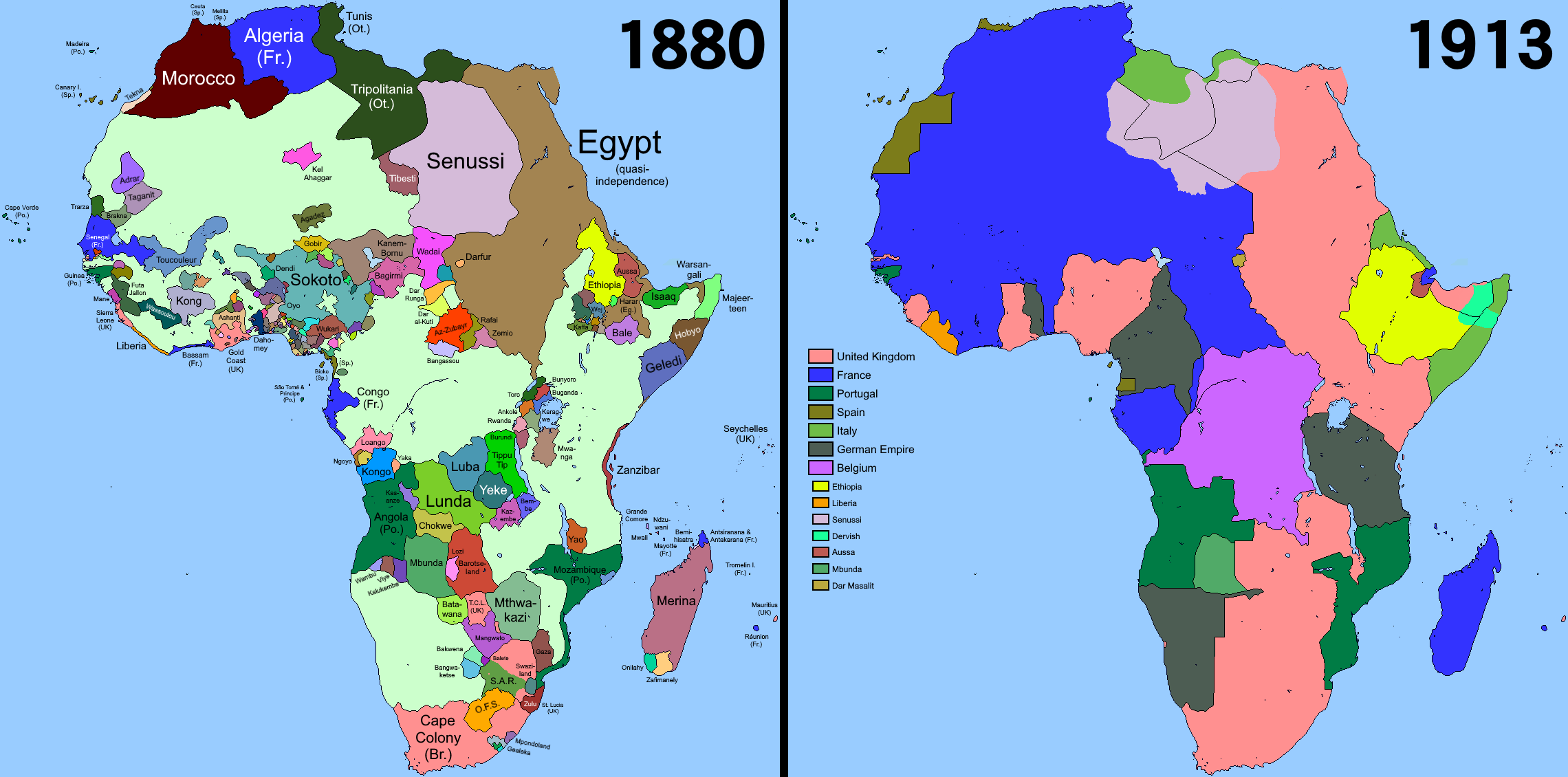

Africa before and after colonization. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The persistence of structural racism and the marginalization of African heritage within Catholic institutions further underscores the need for concrete action. The Church cannot erase its past, but it can be held accountable for it. True reconciliation demands more than words — it requires action. A true reckoning demands urgent action. Without direct restitution and institutional reform, the Church’s complicity in the Black Holocaust will remain an indelible stain on its legacy.

Nyamata Memorial Site, skulls, Nyamata, Rwanda. The skulls exposed are a testimony to the horrors of the 1994 Rwanda genocide – a symbol of remembrance and a call for justice for atrocities committed by institutions in charge. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

References and further reading

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 9 -Mitte des 16. bis Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vom Völkermord in der Neuen Welt bis zum Beginn der Aufklärung, 2010, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499624438

- Saleh, Mohamed; Saleh, Sarah, “Boom and Bust”. Migration in Africa, 2022, 56–74, doi: 10.4324/9781003225027-5ꜛ

- Davis, David Brion, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World, 2006, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195140736

- Blackburn, Robin, The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800, 2010, Verso, ISBN: 978-1844676316

- Thornton, John, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, 1998, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521627245

- Hochschild, Adam, Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves, 2005, Houghton Mifflin, ISBN: 978-0618104697

- Kendi, Ibram X., Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, 2016, Bold Type Books, ISBN: 978-1568584638

- Davis, David Brion, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, 1966, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195056396

- Blackburn, Robin. *The Making of New World Slavery: From the

- Maxwell, John Francis, Slavery and the Catholic Church: The History of Catholic Teaching Concerning the Moral Legitimacy of the Institution of Slavery, 1975, Rose for the Anti-Slavery Society for the Protection of Human Rights, ISBN: 9780859920155

- Copeland, M. Shawn, Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being, 2009, Fortress Press, ISBN: 978-0800662745

- Horne, Gerald, The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century, 2020, Monthly Review Press, ISBN: 978-1583678725

- Noonan, John T. Jr., A Church That Can and Cannot Change: The Development of Catholic Moral Teaching, 2005, University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN: 978-0268036041

- Stuckey, Sterling, Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory and the Foundations of Black America, 2013, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199931675

- O’Malley, John W., The Jesuits: A History from Ignatius to the Present, 2014, Globe Pequot Publishing Group Inc/Bloomsbury, ISBN: 978-1538104293

- Davis, David Brion, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World, 2008, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195339444

- Hochschild, Adam, Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves, 2006, Mariner Books, ISBN: 978-0618619078

comments