The Renaissance Popes: Corruption and power without piety

The Renaissance period (14th–17th centuries) was marked by profound cultural and intellectual renewal, but also by political maneuvering, corruption, and an unprecedented display of secular power by the papacy. During this time, the papal office transformed from a largely spiritual institution into a formidable political entity, deeply entangled in European power struggles. This shift is most glaringly illustrated by the reigns of Sixtus IV, Alexander VI, and Julius II — three pontiffs who embodied the extremes of papal secularization. They actively engaged in nepotism, warfare, and territorial expansion, prioritizing personal ambitions and political dominance over spiritual and theological concerns. Their actions collectively cemented the image of the Renaissance papacy as an era of moral decay and unrestrained secular ambition.

Julius II and Emperor Maximilian I at the Feast of the Rosary, Albrecht Dürer, 1506. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sixtus IV: The architect of nepotism and dynastic ambition

Sixtus IV (r. 1471–1484) was among the first Renaissance popes to embrace an unabashedly secular approach to power. His tenure was defined by rampant nepotism, a practice that would become a defining feature of the period. Sixtus appointed numerous relatives to key ecclesiastical and political positions, not as a means of ecclesiastical reform, but to consolidate his family’s dominance in Rome and beyond.

Portrait of Sixtus IV, Pedro Berruguete, c. 1500, oil on canvas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The pope’s favoritism was particularly evident in his patronage of the Della Rovere family. He appointed his nephews, including Giuliano della Rovere (the future Julius II), to influential cardinalates, ensuring that his lineage maintained a grip on papal politics long after his death. This brazen nepotism not only weakened the credibility of the papacy but also transformed the College of Cardinals into a battlefield of competing aristocratic factions.

Fresco by Melozzo da Forlì, 1477, from left: Giovanni della Rovere, Girolamo Riario, Bartolomeo Platina, Giuliano della Rovere (later Julius II), Raphael Riario, all grandsons of the pope, Sixtus IV. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Sixtus IV was also deeply involved in secular power struggles, notably his role in the infamous Pazzi Conspiracy (1478), an attempt to overthrow the Medici rule in Florence. While the plot ultimately failed, the fact that a pope was orchestrating a violent coup against a powerful ruling family exemplifies the complete abandonment of any pretense of spiritual leadership in favor of secular dominance.

Moreover, Sixtus IV’s massive patronage of the arts, including the commissioning of the Sistine Chapel, served a dual purpose: elevating his personal legacy while reinforcing papal authority through cultural grandeur. However, such expenditures drained the papal treasury, prompting the widespread sale of indulgences — an economic strategy that would later contribute to the eruption of the Protestant Reformation.

Alexander VI: The epitome of corruption and personal excess

Few popes have achieved as notorious a reputation as Alexander VI (r. 1492–1503). Born Rodrigo Borgia, his papacy was characterized by unrestrained hedonism, dynastic ambition, and a willingness to manipulate and betray allies for personal gain. The Borgia name became synonymous with corruption, a legacy Alexander cemented through his political machinations.

Portrait of Pope Alexander VI Borgia, Pedro Berruguete, c. 1495, oil on canvas, Vatican Museums. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

His election in 1492 was itself tainted by simony, with vast sums of money used to secure votes from the College of Cardinals. Once in power, Alexander prioritized the expansion of his family’s influence, particularly through his son, Cesare Borgia, whom he sought to establish as a ruling prince in Italy. Alexander’s use of the papacy as a means to carve out a personal dynasty was unprecedented in its audacity.

His tenure also saw flagrant moral transgressions, including public acknowledgment of his numerous illegitimate children — an act that blatantly contradicted ecclesiastical expectations of celibacy. The opulence and debauchery of the Borgia court further tarnished the Church’s reputation, with rumors of orgies, poisonings, and assassination plots surrounding his reign. The Banquet of Chestnuts (1501), an alleged scandalous orgy held within the Vatican, whether entirely factual or exaggerated by political enemies, became emblematic of the unrestrained excesses of his court.

Portrait of Vannozza dei Cattanei, the mistress of Pope Alexander VI, by Innocenzo di Pietro Francucci da Imola, 1550, oil on canvas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

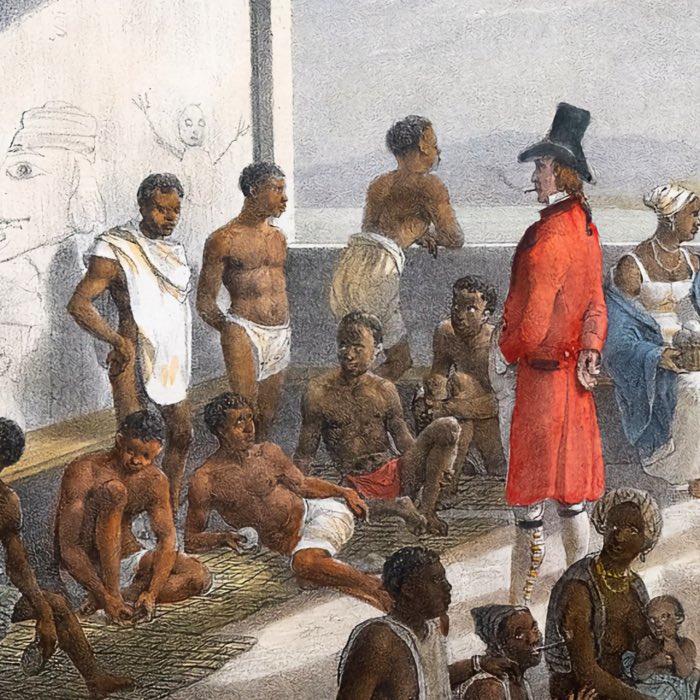

Beyond his personal debauchery, Alexander VI was a ruthless political strategist. His maneuvering during the Italian Wars, shifting alliances between France, Spain, and various Italian states, highlighted his willingness to use the papacy as a political weapon. His most consequential political act was the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which divided the New World between Spain and Portugal, demonstrating the pope’s role in global geopolitics rather than spiritual leadership.

Italy 1494. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Julius II: The warrior pope and the militarization of the papacy

If Sixtus IV and Alexander VI had redefined the papacy as a secular power, Julius II (r. 1503–1513) completed this transformation by openly embracing militarism. Unlike his predecessors, who relied on intrigue and manipulation, Julius preferred direct military confrontation, earning him the title of the “warrior pope”.

Pope Julius II, detail from the Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, fresco in the Raphael Rooms, Raphael, 1511. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Julius II was relentless in his pursuit of territorial expansion for the Papal States. He personally led armies into battle, donning armor and commanding troops in conflicts such as the War of the League of Cambrai (1508–1510) and the conquest of Bologna. His determination to restore papal control over central Italy saw him locked in wars against Venice, France, and various Italian city-states. This aggressive militarization of the papacy shattered any lingering perception of the pope as a purely spiritual leader.

Pope Julius II on the walls of the conquered city of Mirandola, Raffaello Tancredi, 1890, oil on canvas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Despite his militarism, Julius was also a significant patron of the arts, commissioning Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and initiating the construction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica. These projects, though masterpieces of Renaissance art, further drained the papal treasury and necessitated the sale of indulgences — one of the key grievances that would fuel Martin Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517.

Julius commissioning works from Bramante and Raphael, by Alexander Baranov, 1827. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Julius II’s legacy is deeply paradoxical. On one hand, he strengthened the political power of the papacy and solidified control over the Papal States. On the other hand, his militarism, financial extravagance, and indulgence sales directly contributed to the growing disillusionment with the Catholic Church, paving the way for the Protestant Reformation.

Discussion: The transformation of the papacy

The Renaissance period fundamentally altered the nature of the papacy. What had previously been a primarily spiritual institution, albeit with temporal power, fully embraced the characteristics of a secular kingdom. The Papal States, under these popes, functioned as a territorial monarchy with military and diplomatic ambitions comparable to those of contemporary European rulers.

This transformation raises critical questions: Was the papacy ever truly distinct from secular power, or was its Renaissance manifestation merely an evolution of earlier tendencies? By the early 16th century, the papacy had abandoned nearly all pretense of spiritual primacy, instead operating as a princely state. The shift set the stage for later conflicts, particularly the Protestant Reformation, which was fueled in part by outrage over the corruption and worldliness of Renaissance popes. In retrospect, the Renaissance papacy might best be understood as the culmination of a long process of political entanglement — one that, rather than strengthening the Church, ultimately fractured its influence and credibility in Europe.

How did the papacy evolve after the Renaissance?

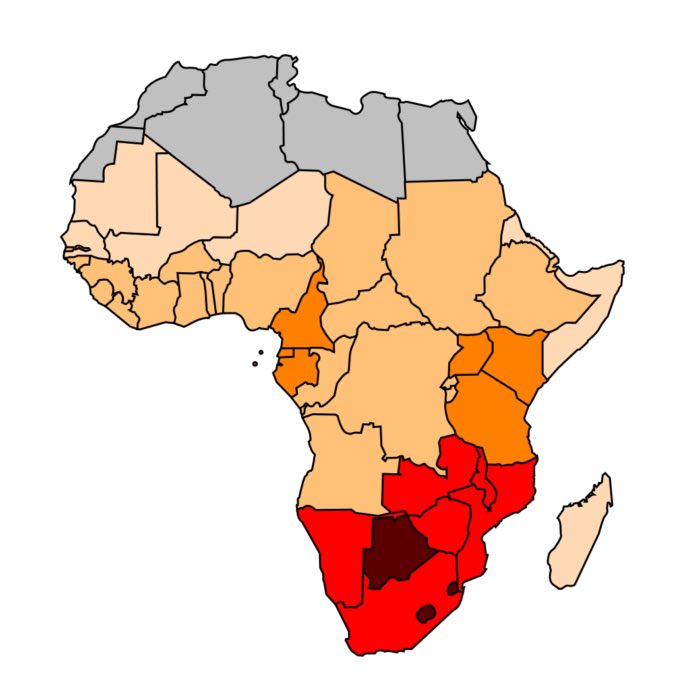

Following the Renaissance, the Papal States continued to function as a secular entity, maintaining significant territorial control in central Italy. However, the shifting political landscape of Europe, particularly the rise of nation-states and the increasing secularization of governance, gradually diminished papal influence as a political force. The 19th century saw the most dramatic change, culminating in the capture of Rome in 1870 by the Kingdom of Italy, effectively ending the Papal States as a political entity. In 1929, the Lateran Treaty between the Holy See and Fascist Italy formally established Vatican City as an independent city-state, redefining the papacy’s role in the modern world. No longer a secular kingdom, the papacy today is primarily a religious authority, exerting global influence through spiritual leadership rather than direct political or military control. However, the echoes of its Renaissance past persist in its diplomatic engagements and the Vatican’s continued presence as a sovereign entity.

The Kingdom of Italy and the Papal States in 1870. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Map of the today’s Vatican City, the successor of the Papal States. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Conclusion

The Renaissance popes exemplified the peak of the papacy’s secularization, shifting its focus from spiritual leadership to political ambition, military conquests, and dynastic power struggles. Their actions, marked by nepotism, corruption, and militarization, redefined the role of the pope, transforming the papacy into a powerful, yet morally compromised, political institution. While their patronage of the arts left behind some of the most iconic cultural and architectural achievements of the Renaissance, their governance significantly eroded the moral authority of the Catholic Church.

This period of unrestrained papal power ultimately sowed the seeds of its own decline, as widespread discontent with corruption and indulgence sales directly contributed to the Protestant Reformation. The gradual secularization of European politics further weakened the temporal influence of the papacy, culminating in the loss of the Papal States in the 19th century.

Though the Vatican today functions primarily as a spiritual and diplomatic entity, the legacy of the Renaissance popes remains an essential chapter in the history of the Church — one that illustrates the dangers of unbridled power and the consequences of prioritizing secular ambition over spiritual integrity.

References and further reading

- Duffy, Eamon, Saints & Sinners: A History of the Popes, 2015, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300206128

- Partner, Peter, Renaissance Rome, 1500-1559: A Portrait of a Society, 1980, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520039452

- Hibbert, Christopher, The Borgias and Their Enemies: 1431-1519, 2009, Mariner Books, ISBN: 978-0547247816

- Shaw, Christine, Julius II: The Warrior Pope, 1997, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 978-0631202820

- Strathern, Paul, The Medici: Power, Money, and Ambition in the Italian Renaissance, 2017, Pegasus Books, ISBN: 978-1681774084

- Norwich, John Julius, Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy, 2012, Random House, ISBN: 978-0812978841

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

comments