The incident of William of Norwich in 1144: The birth of the Blood Libel against the Jews

The case of William of Norwich in 1144 marks the first recorded instance of the blood libel — an accusation that would fuel centuries of anti-Semitic persecution in Europe. This libel falsely accused Jewish communities of murdering Christian children for ritual purposes, embedding a myth that perpetuated hatred, violence, and exclusion against Jews. The story of William of Norwich not only illustrates the devastating impact of religious prejudice but also demonstrates how such myths were exploited for social, political, and economic purposes. Furthermore, it shows how deeply ingrained anti-Semitic attitudes were in the Christian societies theologically and socially, paving the way for centuries of persecution and violence.

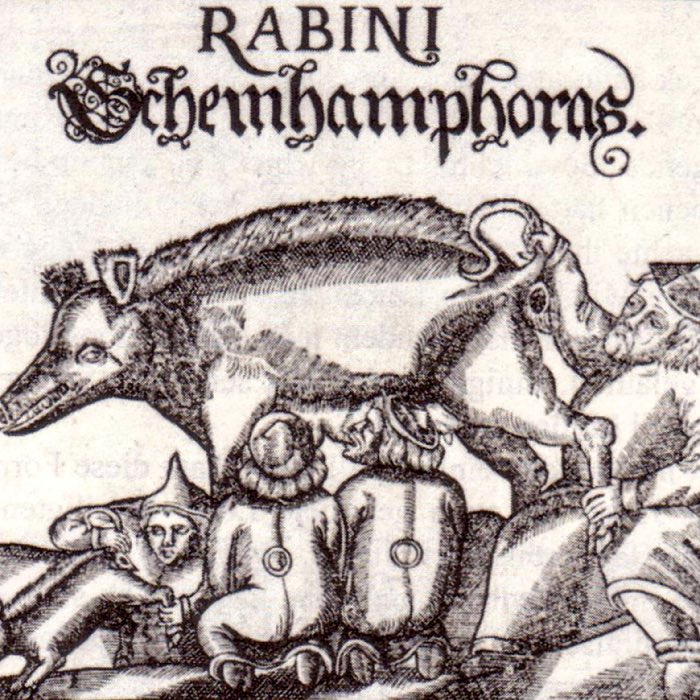

William of Norwich depicted in St Peter and St Paul’s Church, Eye, Suffolk, c. 1500. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical context

By the mid-12th century, Jews in England were a small but significant minority, primarily involved in trade, finance, and other professions restricted to Christians by Church law. Although they were under the protection of the Crown, their status was precarious, as they were often seen as outsiders and scapegoats for social unrest.

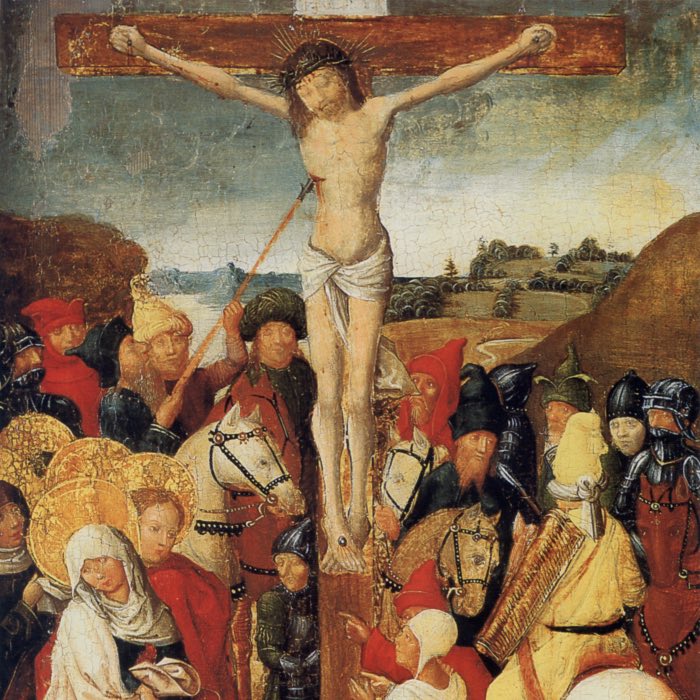

Religious tensions further exacerbated their vulnerability. Medieval Christianity increasingly viewed Jews as culpable for the death of Jesus, and sermons frequently vilified them as dangerous enemies of the faith. This climate of suspicion and hostility set the stage for the blood libel.

The death of William of Norwich

In 1144, the body of a 12-year-old boy named William was discovered in Thorpe Wood, near Norwich. William, an apprentice to a local skinner, was last seen alive on March 20th, Holy Tuesday. His body bore signs of violence, including possible strangulation and minor wounds, though the precise circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

Initially, local authorities and the community suspected that his death was the work of bandits or a tragic accident. However, within weeks, rumors began to take hold, suggesting a far more sinister narrative. Fueled by existing anti-Jewish sentiments and religious superstition, whispers spread that William had been abducted, tortured, and murdered by in a ritualistic act supposedly linked to the celebration of Passover. This accusation, entirely without evidence, would mark the beginning of a dangerous and recurring myth that would have devastating consequences for Jewish communities across Europe.

The role of Thomas of Monmouth

The narrative of William’s supposed martyrdom was primarily constructed by Thomas of Monmouth, a Benedictine monk at Norwich Cathedral. In 1150, Thomas arrived in Norwich and became intrigued by William’s story, eventually writing The Life and Passion of William of Norwich, a hagiography that would popularize the blood libel myth.

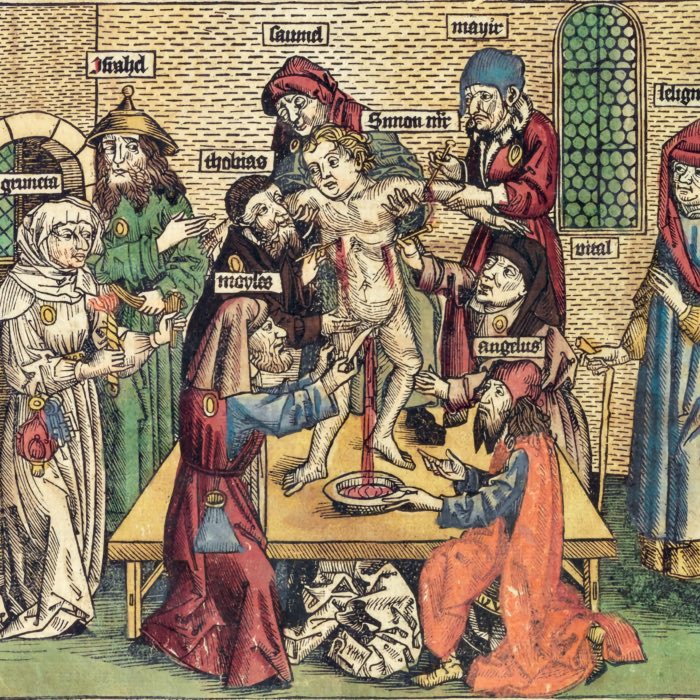

According to Thomas, William had been abducted by Jews, tortured, and crucified in a mockery of Jesus’ Passion. Thomas claimed that this act was part of a Jewish ritual in which Christian blood was used for religious purposes — allegedly to atone for Jewish sins or as a substitute for sacrifices in the Temple.

Thomas’s account was based on hearsay and fabricated confessions extracted under duress. Nevertheless, it became widely circulated and contributed to William’s veneration as a martyr. Despite the lack of evidence, William’s story was exploited to justify further persecution of Jews.

The spread of the Blood Libel

The blood libel against Jews in Norwich set a dangerous precedent. Over the following centuries, similar accusations surfaced in other parts of Europe, including:

- 1190 in Bury St Edmunds, England: Another child martyr was proclaimed (57 Jews were massacred), just 2 days after the York Massacre, leading to the expulsion of the local Jewish community.

- 1255 in Lincoln, England: The alleged martyrdom of Hugh of Lincoln became another pretext for anti-Jewish violence.

- 1475 in Trent, Italy: The case of Simon of Trent resulted in the torture and execution of many Jews, despite the lack of evidence.

In each case, the blood libel was used as a tool to incite violence, extort wealth, or justify expulsions of Jewish communities.

The Blood Libel as a tool of persecution

The blood libel gained traction for several reasons. First, religious propaganda played a crucial role in cementing the myth within Christian societies. The narrative reinforced existing Christian stereotypes of Jews as Christ-killers and agents of evil. It contrasted Christian innocence with alleged Jewish malevolence, providing a theological justification for exclusion and violence.

Second, economic motives were another significant factor. Jewish communities often held important economic roles, particularly in moneylending, a profession largely restricted to them due to Christian prohibitions on usury. Accusations of blood libel provided a convenient pretext for seizing Jewish property, canceling debts, and forcing conversions. Monarchs and local authorities frequently exploited these accusations to confiscate wealth and redistribute it among Christian nobles or the Crown.

And third, social scapegoating also contributed to the spread of the blood libel. In times of crisis, such as famine, economic downturns, or plagues, Jewish communities were often targeted as scapegoats. The blood libel intensified this tendency by portraying Jews as an existential threat to Christian society, fueling widespread fear and mob violence.

The consequences for Jews in England

The blood libel and related accusations culminated in a series of violent pogroms and legal restrictions against Jews in England. These events reinforced deep-seated prejudices and significantly altered the course of Jewish history in medieval England.

One of the most infamous incidents occurred in 1190, during the York Massacre. In this tragic event, a mob, inflamed by anti-Jewish rhetoric and economic grievances, besieged the Jewish community. Seeking refuge in Clifford’s Tower, around 150 Jewish men, women, and children found themselves trapped with no escape. Faced with imminent death at the hands of the violent mob, many chose to take their own lives rather than fall into the hands of their persecutors. The survivors who surrendered were ultimately slaughtered. This massacre was not an isolated event but part of a broader wave of anti-Jewish violence that spread across England during this period.

The mounting hostility and systematic discrimination against Jewish communities culminated in the Edict of Expulsion in 1290, issued by King Edward I. This decree ordered the expulsion of all Jews from England, marking the first official large-scale expulsion of Jews from a European nation. Over the preceding decades, Jewish communities had been subjected to increasing restrictions, including prohibitions on land ownership and heavy taxation. Many were forced to convert to Christianity, and others faced arbitrary arrests and executions. The expulsion was largely motivated by a mix of economic interests and religious intolerance, as Jewish moneylenders had become a target for debt cancellation and royal appropriation of wealth.

Although the Jews were officially allowed to return to England in 1656, their history in medieval England left a lasting scar. The blood libel myth persisted long after their expulsion, influencing anti-Semitic rhetoric and fueling repeated waves of violence against Jewish communities throughout Europe. The enduring power of this myth demonstrates the profound and far-reaching consequences of religious and social scapegoating.

Theological and social implications

The blood libel not only deepened the divide between Christians and Jews but also served as a tool to reinforce existing religious and social hierarchies. By perpetuating myths that demonized Jewish communities, it justified exclusion, violence, and economic marginalization. These accusations were particularly powerful because they leveraged deeply ingrained theological narratives that painted Jews as outsiders and adversaries to Christian society.

Moreover, unchecked prejudice and collective fears were particularly striking in Christian societies, where theological dogma, political structures, and religious institutions often reinforced rigid social boundaries. Unlike many other religious traditions, medieval Christianity was heavily centralized and structured, allowing for the widespread dissemination of ideas that vilified Jews, non-Christians in general, and other minorities such as women and homosexuals. Christian doctrine, enforced through Church edicts and influential clerical authorities — all written by men with rigid theological and social ideas —, shaped societal norms and dictated public attitudes, making such myths difficult to challenge. The concept of religious exclusivity and the idea of heretical threats further fueled intolerance, resulting in widespread social acceptance of baseless accusations like the blood libel.

The ability of religious and political leaders to manipulate these prejudices for economic and social gain made the phenomenon even more persistent. While anti-Semitic sentiments existed in other cultures, Christian Europe uniquely institutionalized these myths in both law and practice, embedding them into the social fabric in ways that endured for centuries.

Ironically, these deeply ingrained prejudices and fabricated accusations starkly contradicted core Christian teachings on love, compassion, and justice. Instead of fostering reconciliation and understanding, religious leaders and political authorities used the blood libel as a means to manipulate public sentiment, directing collective fears and frustrations towards an already vulnerable minority. This distortion of religious values not only fueled centuries of persecution but also demonstrated how fear and prejudice could be systematically weaponized to serve the interests of those in power.

Conclusion

The blood libel myth, which originated with the case of William of Norwich in 1144, became one of the most enduring and damaging anti-Semitic tropes in history. It was repeatedly invoked during the medieval period to justify massacres and expulsions and later resurfaced in early modern Europe, even influencing the propaganda of Nazi Germany.

Despite repeated refutations by scholars and religious authorities, the myth has proven difficult to eradicate, reflecting the power of fabricated narratives in shaping collective memory and social attitudes. The case of William of Norwich illustrates how prejudice, ignorance, and political expediency can converge to construct falsehoods with devastating consequences. The blood libel myth was not merely a product of religious fanaticism; it was also a tool for economic and social persecution, enabling rulers and mobs to justify violence, confiscate property, and reinforce societal hierarchies.

By examining the origins and impact of this and similar myths, we can better understand the dangers of unchecked prejudice — especially in societies where centralized religious and political structures have historically enabled and institutionalized such narratives — and the urgent need to confront and challenge harmful narratives that perpetuate hatred and division.

References and further reading

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 7 12. und 14. Jahrhundert: Von Kaiser Heinrich VI. (1190) zu Kaiser Ludwig IV. dem Bayern (1347), 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498013202

- E. M. Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of Blood Libel in Medieval Europe, 2015, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0190219628

- Katz, Steven (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Antisemitism, 2022, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108714525

- Moore, R. I., The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250, 2006, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405129640

- Nirenberg, David, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, 2018, Head of Zeus, ISBN: 978-1789541168

- Kenneth Stow, Alienated Minority: The Jews of Medieval Latin Europe, 1993, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674015920

- Anna Sapir Abulafia, Christian-Jewish Relations, 1000-1300: Jews in the Service of Medieval Christendom, 2024, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0367552237

comments