John Capistrano: A saint and an anti-semite

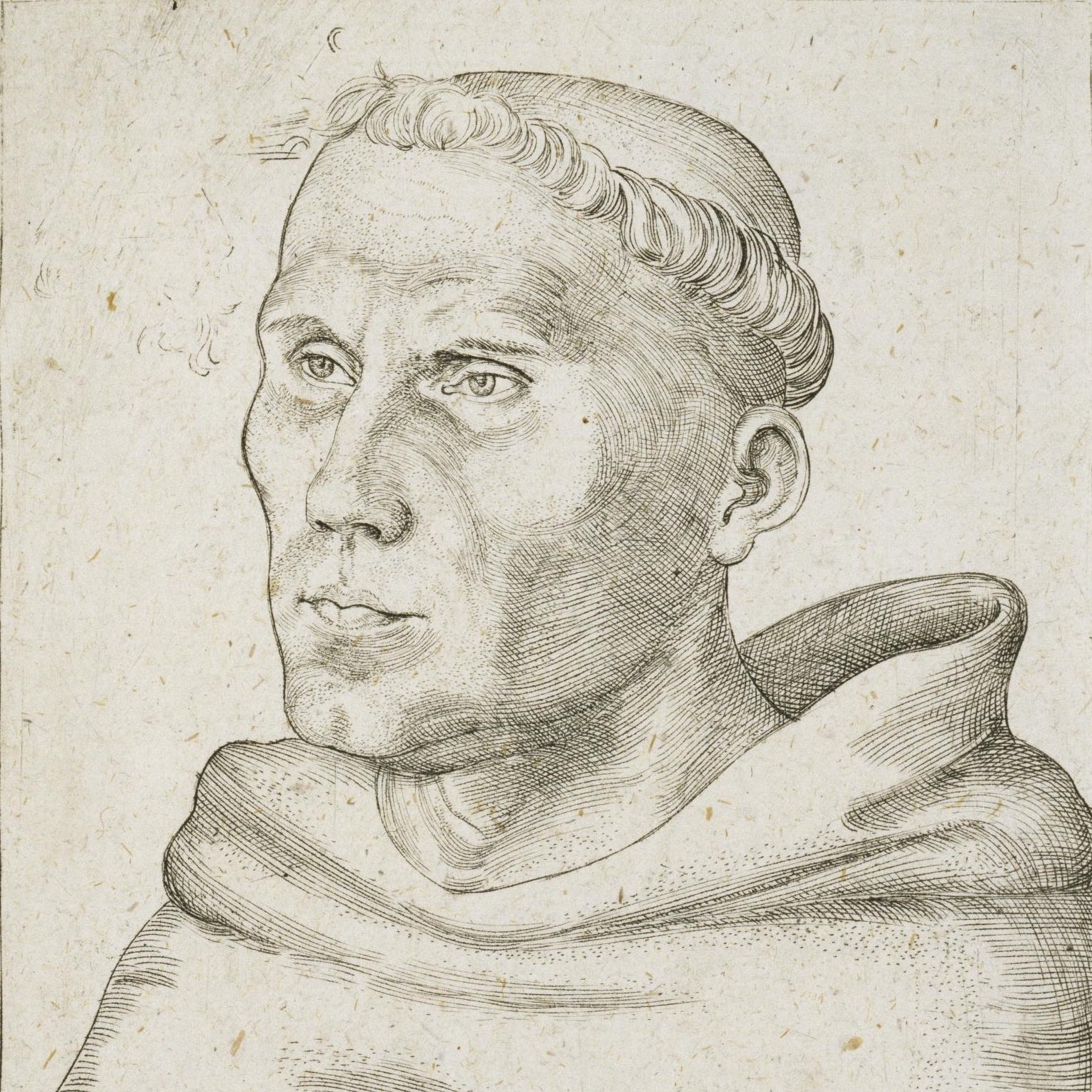

The canonization of John Capistrano, a 15th-century Franciscan friar, missionary, and preacher, raises troubling questions about the moral and ethical standards of sainthood in the Catholic Church. Revered as a saint for his missionary work and his role in the defense of Belgrade against the Ottoman Empire, Capistrano also stands out for his fervent anti-Semitism, incitement to violence, and intolerance. This dual legacy exemplifies the contradictions, moral decay, and institutional cynicism that have marked certain aspects of Church history.

John Capistranus depicted in a Franconian-Bamberg panel painting form 1470/1480. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Who was John Capistrano?

John Capistrano (1386–1456), born in the Kingdom of Naples, was a Franciscan friar who gained fame as a fiery preacher and missionary. He was a staunch supporter of the Church during a time of crisis, including the threat posed by the Ottoman Empire and internal dissent such as the Hussite movement.

Capistrano devoted much of his life to preaching and missionary work, traveling extensively across Europe. His sermons emphasized repentance and strict adherence to Catholic orthodoxy, drawing large crowds and solidifying his reputation as a fervent advocate for Church doctrine. He was particularly renowned for his relentless campaign against perceived heresies and his role in suppressing religious dissent.

During the Ottoman siege of Belgrade in 1456, Capistrano emerged as a significant figure in rallying Christian forces. His impassioned speeches and leadership in mobilizing troops contributed to the city’s defense, earning him the status of a Christian hero in the eyes of many. However, his militancy was not limited to resisting external threats; he also directed his energies inward, against those he considered enemies of the faith.

Capistrano took an uncompromising stance against heretical movements, particularly the Hussites, whom he viewed as a significant threat to the Church’s authority. He advocated for stringent measures against dissenters, including persecution and suppression, reinforcing the Church’s control over religious orthodoxy. His fervor in eradicating heresy reflected a broader pattern of religious intolerance within the Church hierarchy, where deviation from doctrine was met with brutal repression.

Beyond his opposition to heresy, Capistrano was a key instigator of anti-Semitic actions in Central and Eastern Europe. His sermons and influence contributed to widespread persecution, expulsion, and violence against Jewish communities, exacerbating tensions and fueling religious intolerance. He actively promoted the idea that Jews were dangerous enemies of Christianity, leading to violent riots, forced conversions, and official policies of exclusion in several regions.

Canonized in 1690, Capistrano is celebrated for his religious zeal and contributions to Catholicism. However, his anti-Semitic rhetoric and role in inciting violence against Jewish populations stand in stark contrast to the values of compassion and love central to initial Christian core teachings.

Capistrano’s anti-semitism

John Capistrano’s actions toward Jewish communities reflect a disturbing chapter in the history of Christian anti-Semitism. His activities included:

- Incitement to violence

Capistrano’s preaching often targeted Jewish communities, accusing them of deicide (the killing of Christ) and other false charges. His sermons incited mobs to attack Jewish neighborhoods, leading to expulsions, massacres, and destruction of property. - Role in the expulsion of Jews

In Poland, Austria, and other regions, Capistrano’s influence contributed to the expulsion of Jewish communities. His sermons pressured rulers to issue decrees banning Jews from their territories. - Accusations of blood libel

Capistrano propagated the infamous blood libel — the baseless claim that Jews murdered Christian children for ritual purposes. This falsehood was a common pretext for violence against Jews and justified their persecution. - Advocacy for segregation

Capistrano supported policies that isolated Jews from Christian society, including forcing Jews to wear identifying badges and live in segregated areas.

These actions were not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern of systemic anti-Semitism within the medieval Church. Capistrano’s role as an instigator of these atrocities raises serious ethical questions about his canonization and continued veneration.

Canonization and cynicism

The canonization of John Capistrano in 1690 highlights the Church’s historical willingness to prioritize institutional loyalty and militant defense of orthodoxy over moral integrity. By elevating figures like Capistrano to sainthood, the Church sent a message that unwavering adherence to its authority — even when accompanied by violence and intolerance — was more important than embodying the values of love, compassion, and justice.

The glorification of militancy and intolerance

Capistrano’s sainthood reflects the Church’s broader tendency to sanctify figures who furthered its political and institutional interests, even at the cost of fundamental ethical principles. His role in the defense of Belgrade, while significant in resisting Ottoman expansion, was celebrated without regard to the brutality he inflicted on non-Christians, including Jews.

The Church’s canonization of Capistrano not only validated his anti-Semitic actions but also normalized religious persecution as a legitimate means of defending the faith. By doing so, it perpetuated a legacy of hatred, exclusion, and state-sanctioned violence that would be echoed throughout European history.

Institutional cynicism and power consolidation

The veneration of figures like Capistrano reveals a calculated strategy by the Church: aligning itself with militant figures who helped consolidate its dominance over both spiritual and political spheres. Rather than adhering to the core principles of the Gospel, the Church chose to canonize those who demonstrated absolute loyalty and a willingness to suppress dissent — often through violence. This highlights a long-standing pattern of religious institutions manipulating sainthood to justify their expansion and influence.

Conclusion

The life and legacy of John Capistrano exemplify the Catholic Church’s longstanding practice of prioritizing power and institutional control over the ethical values it claims to uphold. His canonization was not an exception or an accident but a deliberate decision within a broader framework in which the Church sanctified figures whose actions reinforced its influence, regardless of their moral transgressions. Capistrano’s anti-Semitic actions and incitement to violence were not aberrations but strategic elements of the Church’s alignment with political rulers.

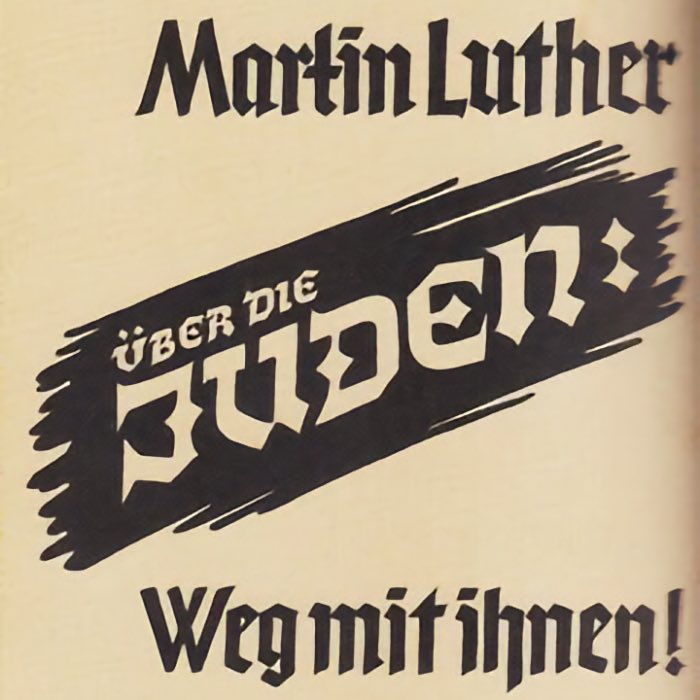

Throughout history, the Church has repeatedly used religious fervor to justify persecution and consolidate authority, as seen in the institutional backing of the Spanish Inquisition, the repeated expulsions of Jewish communities across Europe, and the Church’s role in justifying colonial oppression. Capistrano’s case aligns with this broader pattern, where theological justifications were weaponized to reinforce religious and political control at the expense of marginalized groups. However, what makes his canonization particularly cynical and repugnant is that he was not merely complicit in oppression — he was an active instigator of hatred and violence. The Church did not passively benefit from his actions; it deliberately enshrined him as a model of faith, disregarding the immense suffering he helped cause.

The veneration of Capistrano highlights a deep-seated hypocrisy within the Church’s institutional framework. While it preaches compassion and justice, it has repeatedly chosen to elevate figures whose actions embody the very opposite. By canonizing individuals like Capistrano, the Church not only legitimizes their bigotry but also signals to future generations that religious zealotry and persecution can be pathways to sainthood. Rather than a lapse in moral judgment, his veneration illustrates the Church’s systematic willingness to bend its ethical doctrines whenever they conflicted with its pursuit of dominance and control, revealing the extent to which religious authority has been historically leveraged as a tool of oppression rather than moral guidance.

References and further reading

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Katz, Steven (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Antisemitism, 2022, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108714525

- Moore, R. I., The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250, 2006, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405129640

- Nirenberg, David, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, 2018, Head of Zeus, ISBN: 978-1789541168

- Gábor Klaniczay, Holy Rulers and Blessed Princes: Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe, 2007, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521038997

- Robert Bartlett, Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things? Saints and Worshippers from the Martyrs to the Reformation, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691169682

- Kenneth Stow, Alienated Minority: The Jews of Medieval Latin Europe, 1993, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674015920

- Anna Sapir Abulafia, Christian-Jewish Relations, 1000-1300: Jews in the Service of Medieval Christendom, 2024, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0367552237

comments