The expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290: A precedent for persecution in Europe

The expulsion of Jews from England in 1290 marked one of the earliest formal expulsions of an entire Jewish population from a European nation. This act, carried out under the edict of King Edward I, was a culmination of decades of anti-Semitic policies, economic exploitation, and religious prejudice. The expulsion not only profoundly affected the Jewish community of England but also set a precedent for similar actions across Central Europe, leading to widespread displacement and the migration of Jews to more tolerant regions such as Spain and Eastern Europe. In this post, we explore the historical context, immediate consequences, and long-term legacy of the expulsion.

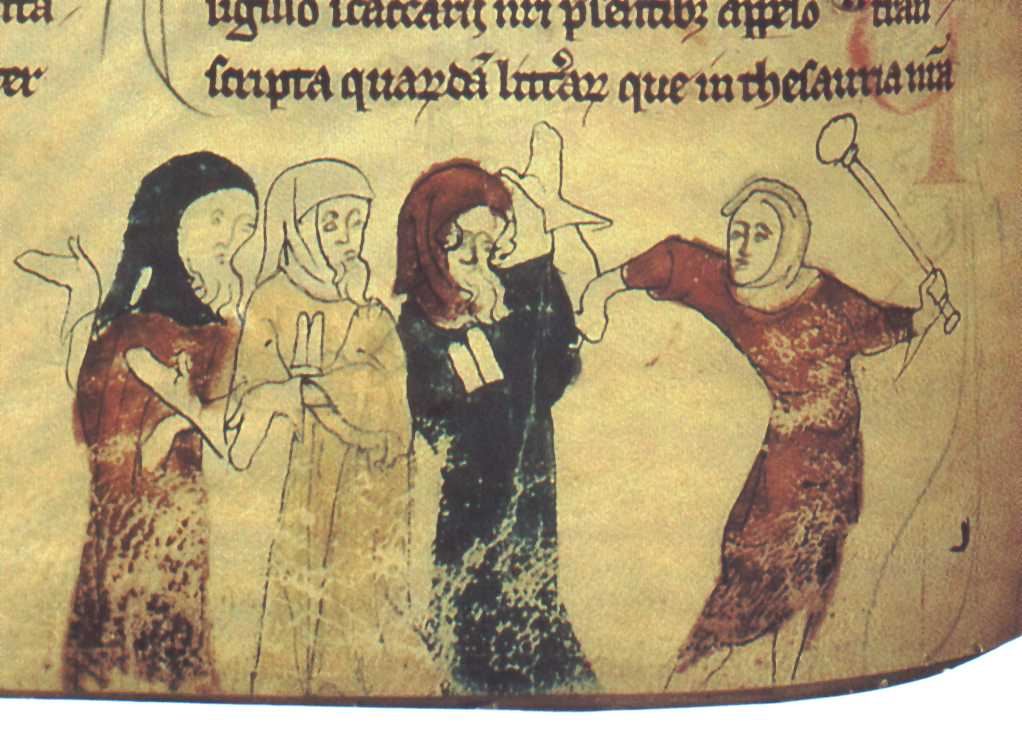

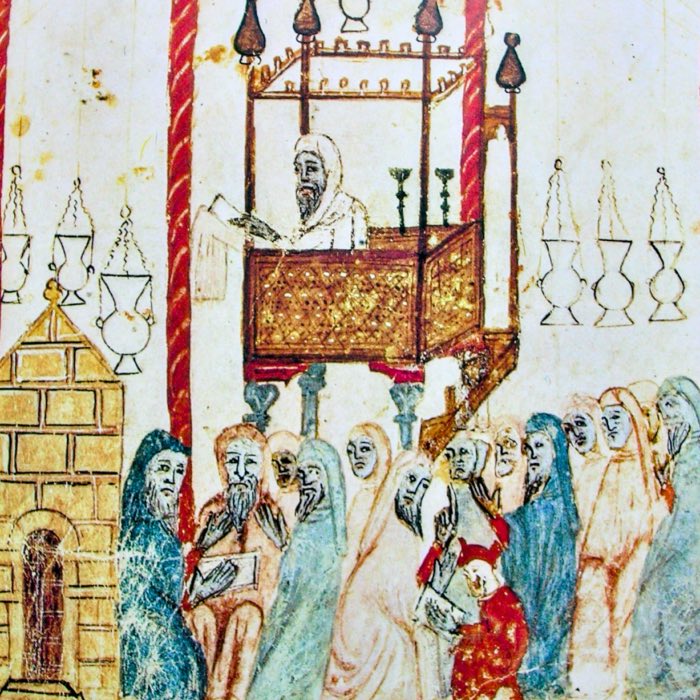

Miniature showing the expulsion of Jews following the Edict of Expulsion by Edward I of England (18 July 1290), Marginal Illustration from the Rochester Chronicle, 14th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical context

Jews were first invited to England following the Norman Conquest in 1066. Under William the Conqueror, Jewish communities played a significant role in the economy, primarily as moneylenders — a profession barred to Christians under Church law. Their position as creditors, however, made them frequent targets of resentment.

Over the next two centuries, Jews in England faced increasing restrictions, hostility, and violence:

- Economic exploitation: The Crown heavily taxed Jewish communities and often confiscated their wealth. Jews were seen as a financial resource, exploited to fund royal projects such as wars and infrastructure.

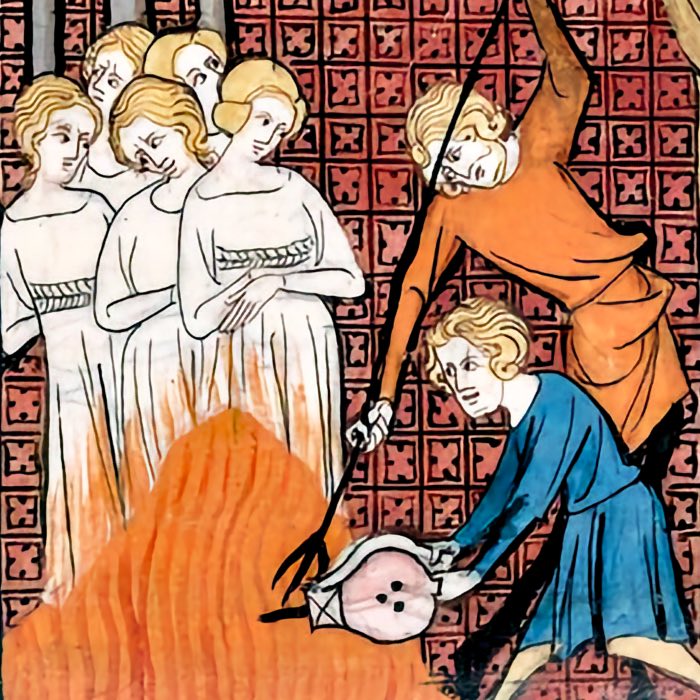

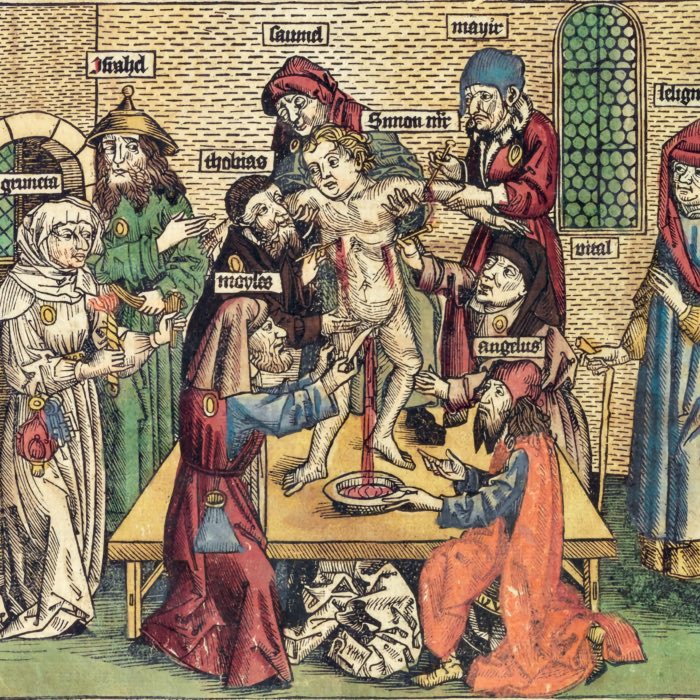

- Religious prejudice: The Church’s anti-Semitic rhetoric, including accusations of usury, desecration of the host, and blood libel, fueled popular animosity against Jews. This religiously motivated hatred was amplified during the Crusades.

- Violence and pogroms: Anti-Jewish riots, such as those in London (1189) and York (1190), resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Jews and the destruction of Jewish property.

By the late 13th century, Jewish communities in England were impoverished, marginalized, and increasingly scapegoated for economic and social tensions.

The edict of expulsion, 1290

On July 18, 1290, King Edward I issued the Edict of Expulsion, ordering all Jews to leave England by November 1 of that year. Approximately 3,000 Jews were forced to leave the country. The reasons for the expulsion were multifaceted:

- Economic factors: By the late 13th century, Jews’ economic utility to the Crown had diminished. Edward I had borrowed heavily from Italian banking families, reducing his reliance on Jewish moneylenders. Expelling the Jews allowed him to seize their remaining assets.

- Religious pressure: The Church increasingly urged rulers to purge their realms of Jewish populations. Anti-Semitic laws passed during the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) required Jews to wear identifying badges and restricted their rights, creating an environment ripe for expulsion.

- Political expediency: The expulsion of Jews was popular among the general Christian population and the nobility, both of whom resented Jewish moneylenders. By expelling the Jews, Edward secured political goodwill.

Immediate consequences of the expulsion

The expulsion of Jews from England had profound consequences for both the Jewish community and the kingdom itself. One of the most immediate effects was the forced migration of the expelled Jewish population. Many sought refuge in other parts of Europe, including France, Spain, and Poland, where they hoped to rebuild their lives. However, their exile did not necessarily lead to stability, as many faced further persecution and expulsion in these regions in the centuries that followed.

From an economic perspective, the removal of Jewish communities had a significant impact on England’s financial system. King Edward I, who orchestrated the expulsion, seized Jewish wealth and debts owed to Jewish moneylenders, temporarily enriching the royal treasury. However, this action also disrupted local economies that had relied on Jewish financial services. Christian lenders eventually filled the void left behind, but their lending practices often imposed harsher terms on borrowers, leading to economic instability and increased financial hardships for many in the kingdom.

Religiously, the expulsion reinforced the dominance of Christianity in England by eliminating one of the few non-Christian communities in the country. This contributed to a growing culture of religious homogeneity, which in turn fostered a climate of intolerance toward other religious minorities. Without the presence of Jewish communities, England became increasingly insulated from religious diversity, a characteristic that would persist for centuries.

A chain reaction of expulsions across Europe

The expulsion of Jews from England set a precedent that influenced similar actions across Central and Western Europe. In the following centuries, Jewish communities were systematically expelled from various territories, often as a means for rulers to consolidate power and seize Jewish assets.

In France, expulsions occurred multiple times, with one of the most significant taking place in 1306 under the reign of Philip IV. The king expelled the Jewish population and confiscated their assets, using the wealth to fund his military campaigns. Despite brief periods of readmission, Jewish communities in France continued to face expulsion and persecution throughout the Middle Ages.

Similarly, various German principalities undertook expulsions in the 14th and 15th centuries. These actions were frequently justified by accusations of usury, blood libel, or host desecration—charges that were often fabricated to provide rulers with a pretext for expelling Jewish populations while benefiting from the confiscation of their wealth. The fragmented political landscape of the Holy Roman Empire meant that while some regions expelled Jewish communities, others provided temporary refuge, leading to ongoing cycles of migration and displacement.

Perhaps the most well-known expulsion was that of Spain in 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella issued the Alhambra Decree, forcing Jews to either convert to Christianity or leave the country. Portugal followed with a similar expulsion in 1496. These expulsions marked the culmination of centuries of tension between Jewish communities and Christian authorities in the Iberian Peninsula. As a result, many Jewish families migrated to more tolerant regions such as the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, and parts of Eastern Europe.

These widespread expulsions created a lasting pattern of displacement, pushing Jewish communities eastward to Poland, Lithuania, and the Ottoman Empire, where they found comparatively greater tolerance. Over time, Eastern Europe became a major center of Jewish life and cultural development.

The migration to Spain and Eastern Europe

Following their expulsion from England and other Western European countries, many Jews sought refuge in Spain and Eastern Europe, regions that offered varying degrees of safety and opportunities for rebuilding their communities.

In Spain, Jewish communities had thrived for centuries, contributing to a flourishing of Jewish culture, philosophy, and scholarship. During the early medieval period, this “Golden Age” saw Jewish intellectuals engage in dialogue with Muslim and Christian scholars, producing remarkable works in science, philosophy, and theology. However, as Christian kingdoms advanced during the Reconquista, the climate shifted, culminating in the harsh anti-Jewish policies that led to the final expulsion in 1492. The Sephardic Jews who left Spain faced a difficult journey, with some settling in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire, while others moved to parts of Italy and the Netherlands.

Eastern Europe, particularly Poland and Lithuania, emerged as new centers of Jewish life in the wake of these expulsions. Polish kings, such as Bolesław the Pious, recognized the economic and administrative skills of Jewish communities and granted them protection and privileges. As a result, Poland became one of the most significant havens for Jewish refugees, leading to the development of a rich and vibrant Jewish culture that persisted for centuries. By the 16th century, Eastern Europe had become the heart of the Jewish diaspora, shaping Jewish identity and communal life well into the modern era.

Conclusion

The expulsion of Jews from England in 1290 was a turning point in medieval Jewish history, setting a precedent for the systematic exclusion of Jews from Western Europe. This event contributed to an enduring cycle of persecution, displacement, and migration that shaped Jewish life for centuries. It underscored the precarious position of Jewish communities, who were both vital to and scapegoated by the societies they lived in.

For England, the expulsion marked the beginning of a nearly 400-year absence of Jewish communities. It was not until the mid-17th century, under Oliver Cromwell, that Jews were officially permitted to return. Meanwhile, the ripple effects of the expulsion influenced policies across Europe, reinforcing shared patterns of intolerance and exclusion. Despite these hardships, Jewish communities adapted and found new centers of settlement, particularly in Eastern Europe, where they contributed to the cultural and economic life of their host societies.

References and further reading

- Katz, Steven (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Antisemitism, 2022, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108714525

- Moore, R. I., The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250, 2006, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405129640

- Nirenberg, David, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, 2018, Head of Zeus, ISBN: 978-1789541168

- Kenneth Stow, Alienated Minority: The Jews of Medieval Latin Europe, 1993, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674015920

- Anna Sapir Abulafia, Christian-Jewish Relations, 1000-1300: Jews in the Service of Medieval Christendom, 2024, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0367552237

comments