Charlemagne…the Great? A critical review of his legacy

Charlemagne, also known as Charles the Great (Latin: Carolus Magnus), holds an exalted place in European history. Revered as a unifier of Europe, a champion of Christianity, and a proto-king embodying European values, he remains a central figure in the medieval imagination. Yet beneath this veneration lies a darker reality: Charlemagne’s rule was marked by violence, conquest, and actions that often stood in stark contradiction to the alleged core Christianity teachings. In this post, we examine the paradox of Charles’ legacy, focusing on his brutal military campaigns, his role in the forced Christianization of peoples, and the Church’s complicity in these acts.

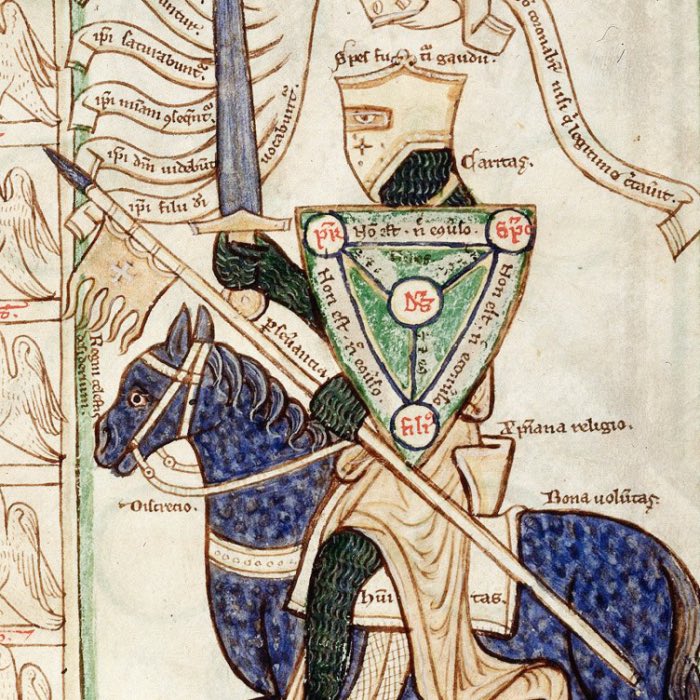

Depiction of Charlemagne in the chronicle of Ekkehard von Aura around 1112/14, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Charlemagne’s military campaigns and Christian values

Charlemagne’s reign (768–814 CE) is often celebrated for his military successes and the expansion of the Frankish Empire. However, his conquests came at a significant human cost, raising questions about their alignment with the Christian values he purportedly championed.

Conquests of Charlemagne. Blue: Frankish Empire 768 at the death of Pepin the Short. Orange: Charlemagne’s conquests between 768-814. Yellow: More or less dependent. Light yellow: Given to Byzantium in 811. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Massacre at Verden (782)

One of the most infamous events of Charlemagne’s reign was the Massacre at Verden. During his decades-long campaign against the Saxons — a pagan people resisting Frankish rule — Charlemagne ordered the execution of approximately 4,500 Saxon men who had been captured and refused to convert to Christianity. The massacre highlights the brutal methods Charlemagne used to enforce Christianity. While he claimed to be spreading the faith, his approach was not one of persuasion or compassion but of coercion, using the sword as his missionary tool. For those who resisted, conversion was a choice between baptism and death.

Charlemagne fighting the Saxons, from a 13th century miniature. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Violence against christians

Charlemagne’s campaigns were not limited to battles against non-Christian peoples. He also waged war against Christian factions, often for political gain rather than religious unity. For instance, his campaigns in Italy and the annexation of Lombard territories were as much about consolidating power as they were about defending the Church. These actions reveal the pragmatic and often hypocritical application of Christian ideals to justify political ambition.

The role of the Church: Complicity and blessing

The Curia, the central governing body of the Roman Catholic Church, actively supported Charlemagne’s campaigns. Far from condemning the violence, the Church provided theological justification for his actions, portraying him as a defender of the faith and a divinely appointed ruler.

The crowning of Charlemagne

In 800 CE, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor, a symbolic act that not only legitimized Charlemagne’s rule but also reinforced the Church’s authority over secular governance. This coronation was a pivotal moment in medieval history, intertwining religious and imperial power in a way that shaped European politics for centuries. However, it also underscored the Church’s strategic alliance with rulers who were willing to defend its interests, regardless of their methods. Charlemagne’s violent campaigns, including forced conversions and military suppression, were overlooked in favor of his role as a unifying figure. By crowning him, the papacy reinforced the notion that divine approval could be bestowed upon rulers who furthered its influence, even at the expense of fundamental Christian principles.

Pope Leo III crowning Charlemagne. From Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis, volume 1, France, second quarter of the 14th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Forced christianization

The Church’s complicity in Charlemagne’s campaigns extended to its full endorsement of forced Christianization. Under his rule, conversion was not a spiritual calling but an obligation enforced by law. Charlemagne’s Capitulary on the Saxon Territories (785 CE) mandated the death penalty for those who refused baptism, desecrated churches, or practiced traditional pagan rituals. Entire communities were given ultimatums: accept Christianity or face execution. This policy starkly contradicted the foundational Christian idea of free will in matters of faith. Rather than spreading Christianity through persuasion and example, Charlemagne and the Church used military conquest and coercion, transforming religion into a political instrument of control. Consequently, this approach not only bred resentment among the subjugated populations but also set a precedent for the use of faith as a justification for imperial expansion.

Conversion of the Saxons, A. de Neuville, c. 1869. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Charlemagne as a proto-European king: The irony of his legacy

Charlemagne is often portrayed as a unifier and a symbol of European identity. His promotion of education, legal reform, and cultural revival — collectively known as the Carolingian Renaissance — are frequently cited as evidence of his progressive and enlightened rule. However, this narrative obscures the darker aspects of his reign.

The betrayal of Christian values

The core teachings of Christianity emphasize humility, compassion, and the rejection of violence. Charlemagne’s actions, particularly his use of violence to impose religious conformity, represent a profound betrayal of these principles. The irony of his legacy lies in the fact that the Church, which should have upheld these values, actively facilitated his militaristic approach. Instead of advocating for peaceful conversion and moral persuasion, the Church endorsed his coercive measures, using religious justification to advance its own authority. This collaboration blurred the line between faith and political dominance, embedding religious violence into the foundations of European Christendom.

For his victims

For the Saxons, the Avars, and other peoples subjected to Charlemagne’s campaigns, his reign was not a golden age but a time of suffering, oppression, and loss. Entire communities were forcibly displaced, sacred traditions were dismantled, and resistance was met with extreme brutality. To these populations, Charlemagne was not a noble ruler but an agent of cultural destruction, whose actions exemplified the worst abuses of power cloaked in religious justification. His policies did not lead to the peaceful spread of Christianity but rather sowed deep resentment and enduring scars among those who were subjugated under his rule.

The “triumph” of the Church

Charlemagne’s reign marks a critical moment in the history of the Catholic Church. By aligning itself with a powerful ruler, the Church secured its political dominance and expanded its influence across Europe. However, this alliance came at a moral cost, as it reinforced the use of violence and coercion in religious matters, contradicting the fundamental principles of Christian doctrine.

A Church of power, not principle

The partnership between Charlemagne and the Church symbolized another shift from a faith centered on spiritual teachings to an institution driven by political ambition. By legitimizing Charlemagne’s militarized expansion, the Church further transformed itself into an agent of state power, using religious justification to maintain and extend its reach. This “triumph” of Christianity as a dominant political force was built on a foundation of forced conversions, suppression of dissent, and strategic alliances, raising lasting questions about the consequences of intertwining religious authority with imperial rule.

Long-term consequences

The alliance between Charlemagne and the Church shaped the medieval power structure, reinforcing the idea that rulers could wield religious legitimacy as a political tool. This precedent influenced later European monarchs, who justified their authority through divine sanction. The fusion of imperial and religious authority laid the groundwork for the Holy Roman Empire, a political entity that would dominate European politics for centuries (see, e.g., the “two swords” doctrine). Additionally, Charlemagne’s methods of forced conversion established a model that resurfaced in later religious conflicts, from the Crusades to the Inquisition. Rather than spreading Christianity through faith and conviction, his reign demonstrated how religion could be weaponized to consolidate political control.

Conclusion

Charlemagne’s portrayal as a proto-Christian king and a symbol of European values is fraught with irony. While he is celebrated for “uniting” Europe and defending Christianity, his methods — including the slaughter of entire peoples and the imposition of faith through violence — stand in stark contrast to the alleged core teachings of Christianity. The Church’s endorsement of these actions further underscores the moral compromises it made in its pursuit of power.

For all his achievements, Charlemagne’s legacy cannot be disentangled from the suffering he caused and the values he betrayed. His reign illustrates how power, when intertwined with religious justification, can reshape societies but also erode the very principles it claims to uphold. Rather than a pure symbol of unity or faith, Charlemagne’s legacy is a reminder that historical greatness often comes at a cost — one measured not just in achievements, but also in the lives affected by them.

Europe at the death of the Charlemagne in 814. Whenever we see maps of great conquerers, which always let us feel impressed by their achievements, we should also remember the human cost of these conquests. In history, almost any conquest was accompanied by violence, suffering, and loss, which is completely forgotten in the grand narratives of “greatness”, true to the motto: “History is written by the victors”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

References and further reading

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums4. Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

- Egon Boshof, Die Geschichte des Christentums – Mittelalter 1: Bischöfe, Mönche und Kaiser (642-1054), 2007, Herder, Ungekürzte Sonderausgabe, Hrsg.: Norbert Brox, Jean-Marie Mayeur, Charles Piétri, Luce Piétri, ISBN: 978-3-451-29372-6

comments