The fall of the Western Roman Empire and the role of Christianity during the Migration Period

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE and the subsequent migration and settlement of Germanic and Gothic peoples marked a transformative period in European history. While these events often evoke images of chaos and decline, they also created fertile conditions for the spread of Christianity. Far from being a passive beneficiary, Christianity actively adapted to and shaped the political and cultural dynamics of the post-Roman world. The religion’s message, institutional flexibility, and ability to integrate with existing social and political structures enabled it to thrive among the migrating peoples, ultimately becoming the unifying spiritual framework of medieval Europe. This post examines the relationship between the migration of peoples, the fall of the Western empire, and the spread of Christianity, focusing on its adoption by Germanic and Gothic kings and their inhabitants, culminating in Charlemagne’s Christian empire. We explore how the disruptions of Late Antiquity contributed to Christianity’s ascendancy as both a religious and political force.

Barbarian invasions of the Roman Empire from 100-500 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

The decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire was not a singular catastrophic event but a gradual process spanning centuries. Multiple factors contributed to its decay, including economic instability, military decline, internal strife, and external invasions. Over time, these pressures weakened Rome’s ability to maintain control over its vast territories.

Economic and administrative decline

Rome’s economy faced significant strain due to a combination of excessive taxation, rampant inflation, and an overreliance on slave labor, which stifled technological progress and innovation. As agricultural production declined, food shortages and economic disparity widened, exacerbating social unrest. The empire’s inability to reform its tax system further weakened its financial base, making it increasingly difficult to fund the military and public infrastructure. Corruption and administrative inefficiency pervaded the government, with positions often sold to the highest bidder rather than awarded based on merit. The deterioration of governance led to weakened central authority and an inability to effectively manage the vast territories of the empire.

Military weakness and external invasions

The decline of Rome’s military prowess was a crucial factor in its downfall. The Roman legions, once a formidable force, increasingly relied on mercenaries, many of whom were Germanic warriors with uncertain allegiances. This reliance on foreign troops eroded Rome’s military discipline and effectiveness. The empire faced relentless pressure from barbarian groups, including the Visigoths, Vandals, and Huns. In 410 CE, Alaric and his Visigothic forces successfully sacked Rome, a symbolic event that underscored the empire’s vulnerability. Later, in 455 CE, the Vandals launched another devastating attack on the city, further illustrating Rome’s deteriorating ability to defend itself. The empire’s border defenses crumbled, allowing waves of invaders to push deeper into Roman territory, overwhelming an already weakened system.

The deposition of the last emperor

The final blow to the Western Roman Empire came in 476 CE when the Germanic chieftain Odoacer deposed the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus. Unlike his predecessors, Romulus wielded little real power, and his removal was met with little resistance. Rather than establishing a new Roman ruler, Odoacer declared himself King of Italy, marking the definitive end of Roman imperial rule in the West. This transition led to a power vacuum that was filled by various Germanic kingdoms, which established their own rule over former Roman territories. Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman Empire, later known as the Byzantine Empire, persisted for nearly a thousand more years, continuing to influence European and Mediterranean affairs long after the fall of the Western Roman world.

The role of Christianity during the Migration Period

By the 4th century CE, Christianity had already gained a foothold within the Roman Empire, culminating in Emperor Constantine’s Edict of Milan in 313 CE, which granted it legal status. The subsequent Edict of Thessalonica in 380 CE declared Christianity the official religion of the empire. As the Western Roman Empire crumbled under internal decay and external pressures, Christianity emerged as a source of stability and continuity.

The Church as a stabilizing force

With the erosion of Roman administrative structures, the Christian Church stepped into roles previously occupied by imperial authorities. Bishops, particularly in urban centers like Rome, became key political and social leaders, providing governance, mediating disputes, and maintaining social order. The Church’s well-established hierarchy and network of dioceses allowed it to exert influence across fragmented territories.

Christianity’s appeal to Germanic and Gothic peoples

The Christian message of hope, salvation, and a universal moral order resonated with many of the migrating peoples who encountered the declining empire. The structured rituals and teachings of the Church offered a framework for spiritual and social coherence, while its emphasis on loyalty and communal values aligned with the kinship-based societies of Germanic and Gothic tribes.

Conversion and integration: Germanic and Gothic peoples

The conversion of Germanic and Gothic tribes to Christianity was a gradual and multifaceted process, influenced by political, cultural, and missionary efforts. These conversions were not merely spiritual but also deeply political, as tribal leaders sought alliances with Christian authorities and adopted the faith to legitimize their rule.

The conversion of the Goths

The Gothic peoples, particularly the Visigoths, were among the first Germanic tribes to adopt Christianity. Their conversion began in the 4th century under the influence of the missionary Ulfilas, who translated the Bible into the Gothic language. Notably, the Visigoths embraced Arian Christianity, a theological perspective that viewed Christ as subordinate to God the Father, in contrast to the Nicene orthodoxy upheld by the Roman Church.

The adoption of Arianism by the Goths highlights the interplay between theological and political factors. Arian Christianity distinguished the Goths from the Roman populace, allowing them to maintain a distinct identity while aligning with Christian beliefs. However, this theological divergence later created tensions between Gothic rulers and the Roman Church, shaping the dynamics of religious and political integration.

Frankish conversion and the rise of the Merovingians

The conversion of the Franks under King Clovis I in the late 5th century marked a turning point in the Christianization of Europe. Unlike the Goths, Clovis embraced Nicene Christianity, aligning his kingdom with the Roman Church. This decision strengthened his legitimacy as a ruler and facilitated alliances with the Romanized Gallo-Christian elite.

Clovis’s baptism by Bishop Remigius of Reims symbolized the integration of Frankish kingship with Christian authority, setting a precedent for the close relationship between Church and state in medieval Europe. The Frankish embrace of Christianity also enabled the Church to extend its influence into regions previously beyond the reach of Roman control.

The role of missionaries and monasticism

Missionary activity played a critical role in the spread of Christianity among the migrating peoples, particularly in regions beyond the former Roman borders. Monastic communities, with their emphasis on learning, piety, and practical service, became centers of cultural exchange and religious transformation.

Missionaries to the Germanic peoples

Figures such as St. Patrick in Ireland, St. Augustine of Canterbury in England, and St. Boniface in Germany were instrumental in converting Germanic and Celtic populations to Christianity. These missionaries often adapted their approach to local customs and beliefs, incorporating elements of indigenous spirituality into Christian practices.

For example, St. Boniface’s felling of the sacred Donar Oak in the 8th century symbolized the triumph of Christianity over paganism, serving as a deliberate act of religious and political domination. The destruction of this sacred site was meant to demonstrate the power of the Christian God over traditional Germanic deities and to undermine local pagan belief systems. The wood was subsequently used to construct a Christian chapel, further reinforcing the authority of the Church in the newly converted regions. Such actions exemplify the Church’s strategic and often forceful approach to missionary work, which combined theological rigor with the suppression of indigenous traditions.

Monasticism as a cultural bridge

Monasticism emerged as a powerful force for Christianization, particularly in rural and frontier regions. Monasteries served as centers of education, agriculture, and administration, providing a model of communal life that resonated with tribal societies. The Rule of St. Benedict, with its emphasis on discipline, prayer, and labor, became a blueprint for monastic life and a key vehicle for the spread of Christianity.

Charlemagne and the culmination of Christianization

The Christianization of Europe reached its zenith under Charlemagne (768–814), whose reign marked the consolidation of Christian rule in the Frankish Empire and the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire. Charlemagne’s policies reflected a synthesis of Roman, Frankish, and Christian traditions, creating a unified political and religious framework that shaped medieval Europe.

Charlemagne’s religious reforms

Charlemagne actively promoted the Christianization of his empire through a combination of military conquest, legislation, and patronage of the Church. He supported the establishment of schools, the standardization of liturgical practices, and the production of religious texts, fostering a cultural revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance.

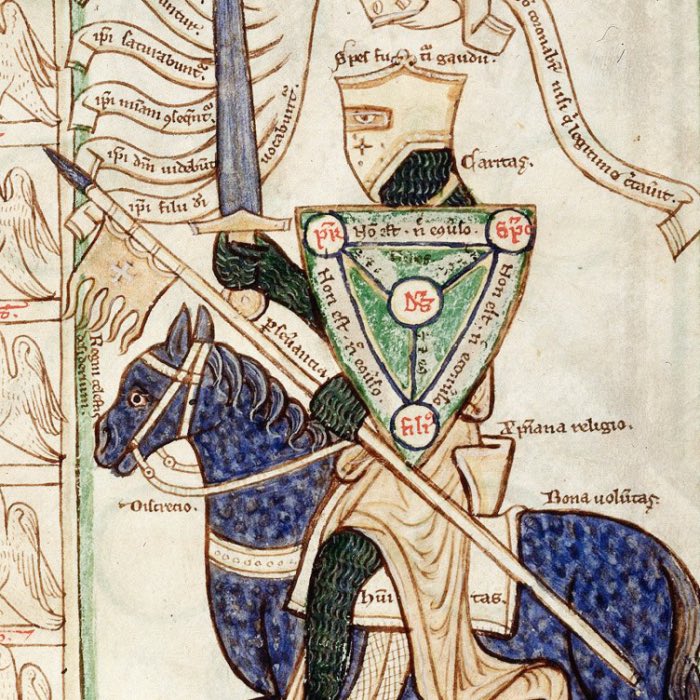

The forced conversion of the Saxons during Charlemagne’s campaigns illustrates the dual role of Christianity as both a spiritual and political force. Theological-ideological legitimacy for such measures were provided by ecclesiastical authorities and doctrines such as the concept of the “just war” by Augustine of Hippo. These were coercive measures aimed at facilitating the integration of the various tribal groups into a unified Christian community.

The legacy of the Christian empire

Charlemagne’s coronation as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800 symbolized the fusion of Christian and imperial authority, cementing the Church’s central role in European governance. This alliance between the Frankish monarchy and the Roman Church provided a model for the relationship between Church and state, also known as the “two swords” doctrine, that would persist throughout the Middle Ages.

The Church in the Eastern Roman Empire

While the Western Roman Empire collapsed, the Eastern Roman Empire, commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, not only survived but flourished. Unlike in the West, where the Church stepped into the power vacuum left by the Roman administration, the Church in the East remained closely integrated with the imperial government.

The role of the Church in Byzantine politics

From the time of Emperor Constantine, the Eastern Church enjoyed a privileged position within the state. Byzantine emperors considered themselves both political and spiritual leaders, a concept known as “Caesaropapism”. Unlike the decentralized structure that developed in the West, where bishops and the Pope gained independent power, the Patriarch of Constantinople remained subordinate to the emperor. This close relationship allowed the emperor to control religious doctrine, appoint bishops, and intervene in theological disputes.

Theological developments and conflicts

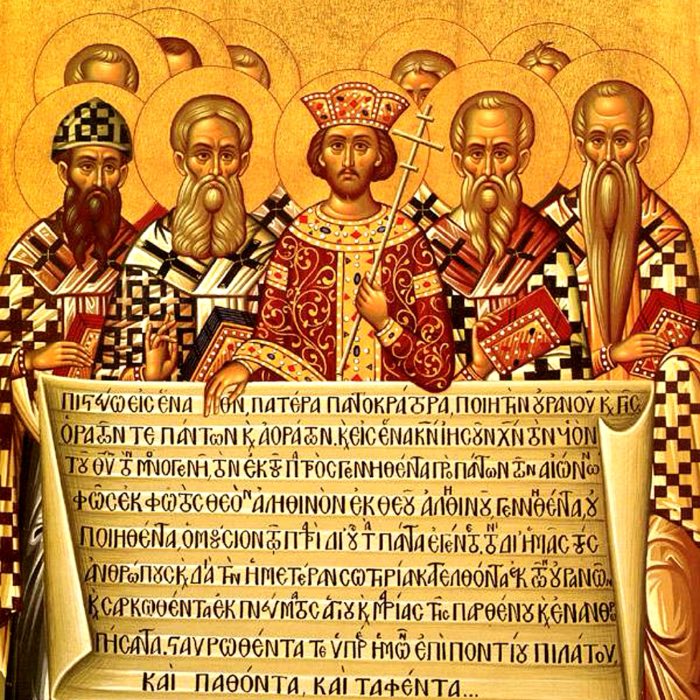

The Eastern Church became the center of major theological debates, many of which shaped the development of Christianity as a whole. Key controversies, such as the Arian dispute, the Nestorian schism, and the Monophysite controversy, were often intertwined with imperial politics. The councils convened in the East, such as the Council of Nicaea (325 CE) and the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE), set doctrinal standards that defined Orthodox Christianity and influenced the entire Christian world.

The emergence of Orthodox Christianity

Over time, the Church in the East developed distinct theological traditions and liturgical practices, leading to what is now known as Eastern Orthodoxy. The use of Greek rather than Latin, the emphasis on mystical theology, and the iconographic traditions of the Byzantine Church set it apart from the Roman Catholic Church. This divergence eventually culminated in the Great Schism of 1054, which formally separated the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches.

The Church as a stabilizing force in the Byzantine Empire

Much like in the West, the Church in Byzantium played a stabilizing role in society, but in a different way. The strong relationship between the emperor and the Church ensured religious unity within the empire. Monasticism flourished, with monastic communities becoming centers of learning, manuscript preservation, and missionary work. Unlike the West, where monasteries helped integrate Germanic peoples into Christianity, Byzantine monasticism played a role in converting Slavic peoples and spreading Orthodox Christianity to Eastern Europe.

Conclusion

The migration of peoples and the fall of the Western Roman Empire created conditions that paradoxically favored the spread of Christianity. As Roman administrative structures crumbled, the Church emerged as a stabilizing force, offering spiritual, social, and political cohesion to fragmented societies. The conversion of Germanic and Gothic tribes, facilitated by missionary activity and pragmatic adaptation, extended Christianity’s reach beyond the former Roman borders.

The culmination of this process under Charlemagne marked the establishment of a Christian Europe, where faith and governance were intertwined. By adapting to the challenges of a changing world, Christianity not only survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire but emerged as the defining spiritual and cultural force of medieval Europe.

References and further reading

- Heather, Peter, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, 2006, Pan Macmillan, ISBN: 978-0525566656

- Brown, Peter, The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000, 2013, Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 978-1118301265

- Fletcher, R., The barbarian conversion: from paganism to Christianity, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520218598

- Noble, T. F. X., The Republic of St. Peter: the birth of the Papal State, 680–825, 1986, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN: 978-0812212396

- Wallace-Hadrill, J. M., The Frankish Church, 1983, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198269069

- Beard, Mary, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, 2016, Profile Books, ISBN: 978-1846683817

comments