Pope Leo I: The architect of papal primacy and the foundations of Roman Christianity

Pope Leo I, known as Leo the Great (r. 440–461 CE), played a transformative role in shaping the self-identity of the Catholic Church and the role of the papacy. His pontificate came at a pivotal moment in the history of Christianity, as the Roman Empire faced profound crises, both internal and external. Leo’s theological contributions, political actions, and strategic emphasis on the centrality of the Bishop of Rome not only elevated the papacy’s authority but also laid the groundwork for the institutional Church’s consolidation of power. This post examines how Leo’s assertions of temporal and spiritual authority, his theological framing of Peter and Paul, and his role in defining Roman Christianity set the stage for the papacy’s influence and the Church’s evolving relationship with political power.

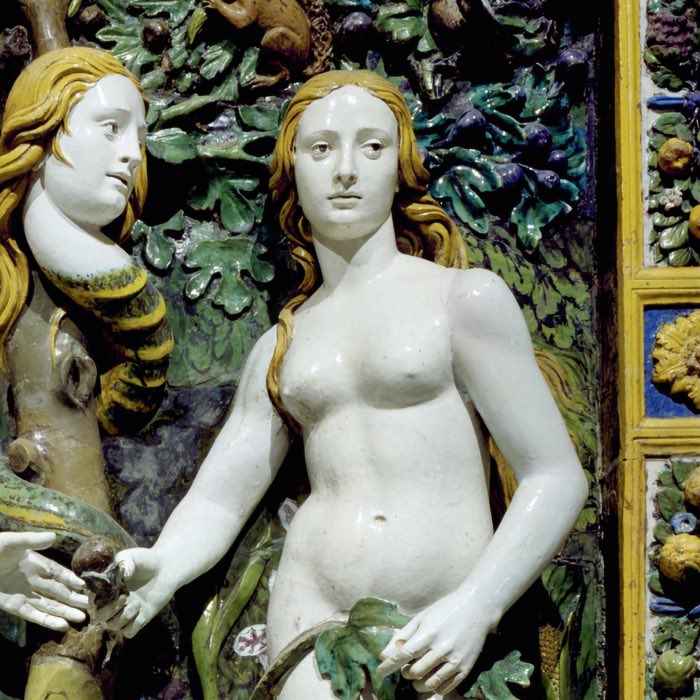

Leo I with Attila, from a book illumination, 14th century. When Rome was threatened by the Huns under Attila in 452, Leo confronted the Hun king outside Mantua and (at least according to some sources) probably prevented the Huns from advancing towards Rome by paying a large sum of money. However, Attila was in fact already in retreat and by no means on his way to Rome, so that some of the reports probably exaggerate Leo’s role. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical context: Crisis and opportunity in the late Roman Empire

The mid-5th century was a period of profound instability for the Roman Empire. The Western Empire faced relentless invasions by barbarian tribes such as the Huns and Vandals, while internal divisions and weakening imperial authority left Rome vulnerable. The Church, once a persecuted minority, had by this time gained significant influence, benefiting from Emperor Constantine’s earlier recognition of Christianity and its subsequent elevation to the status of the state religion under Theodosius I in 380 CE.

However, this newfound prominence brought challenges. The Church was no longer a grassroots spiritual movement but an institution increasingly entangled in imperial politics and burdened with theological disputes. It was in this environment that Pope Leo I ascended to the papacy, a position that had yet to fully assert its dominance over other patriarchates in Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

The doctrine of papal primacy: Leo’s vision for the papacy

One of Leo’s most enduring contributions was his articulation of the doctrine of Petrine primacy, which asserted the preeminence of the Bishop of Rome over the entire Christian Church. Drawing on the Gospel of Matthew (16:18), where Jesus is said to have declared Peter the “rock” upon which the Church would be built, Leo framed the Roman papacy as the direct successor to Peter’s apostolic authority. This was not merely a theological argument but a deliberate strategy to centralize ecclesiastical power in Rome.

Leo emphasized that Peter’s authority, as conferred by Christ, was unique and passed exclusively to the Bishops of Rome. In a sermon commemorating Peter and Paul, Leo proclaimed:

“The blessed Peter perseveres in the strength of the rock, which he has received, and does not abandon the helm of the Church, which he once accepted.”

This assertion established a theological and symbolic link between the papacy and divine authority, elevating the Roman bishopric above its rivals. By presenting Rome as the city sanctified by the blood of Peter and Paul, Leo further reinforced the notion that the Roman Church was uniquely endowed with spiritual and historical significance.

Temporal authority and the papacy’s political role

Leo’s assertion of papal primacy extended beyond theological matters to encompass temporal authority. The most emblematic example of this was his confrontation with Attila the Hun in 452 CE. According to tradition, Leo personally negotiated with Attila, persuading him to withdraw his forces from Italy. While the precise details of this encounter remain unclear, it symbolized the growing role of the papacy as a protector of the Roman populace and a mediator in political crises.

This episode, combined with Leo’s broader efforts to position the papacy as a stabilizing force in a crumbling empire, marked a significant expansion of the papacy’s temporal influence. By stepping into roles traditionally held by imperial officials, Leo positioned the papacy as both a spiritual and political authority, a dual role that would define the Church for centuries.

Peter, Paul, and the Romanization of Christianity

Leo’s emphasis on the martyrdom of Peter and Paul in Rome was central to his strategy of elevating the Roman Church. By tying the Church’s authority to these apostolic figures, Leo not only bolstered the papacy’s claim to universal jurisdiction but also provided a powerful narrative of continuity and legitimacy.

Peter, as the “rock” of the Church, represented authority and stability, while Paul, the missionary to the Gentiles, symbolized the Church’s universal mission. By celebrating their combined legacy, Leo framed the Roman Church as the guardian of apostolic tradition and the unifying force in Christendom. This emphasis on Rome’s unique role also served to marginalize other patriarchates, consolidating power within the Roman bishopric.

A Church religion diverging from original Christian teachings?

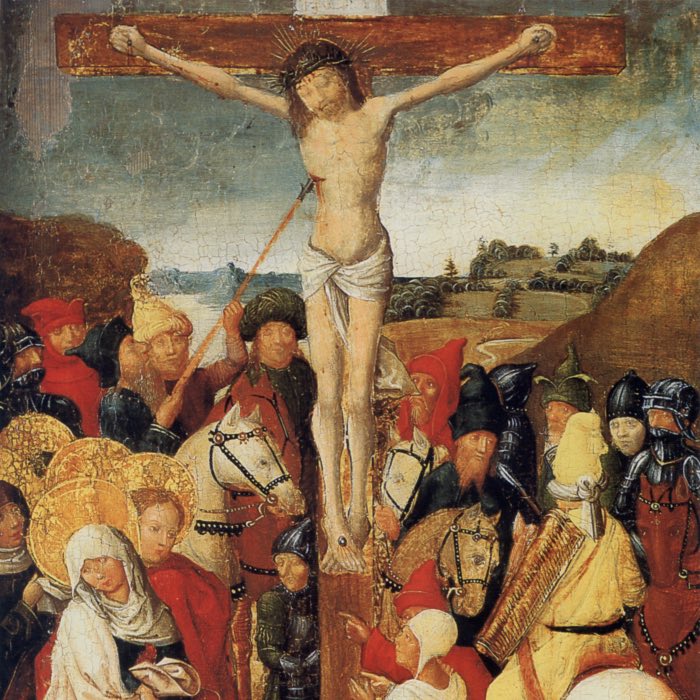

Leo’s actions, while instrumental in unifying and strengthening the Church, also marked a significant departure from the egalitarian and spiritual ethos of early Christian’s core teachings. The Gospels emphasize humility, service, and the rejection of worldly power (e.g., Matthew 23:8–12, John 13:14–15). In contrast, Leo’s papacy laid the groundwork for a hierarchical and institutionalized Church that wielded both spiritual and temporal power.

- Institutionalization and centralization:

The centralization of authority in Rome under Leo shifted Christianity from an already hierarchical but regionally diverse Church into a more centralized institution with the Bishop of Rome asserting greater authority over other patriarchates. This transformation distanced the Church from its origins as a grassroots movement of mutual support and spiritual practice. - Theological exclusivity:

Leo’s role in the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE) exemplified the growing dogmatization of Christian theology. While the council resolved key Christological debates, it also marginalized dissenting views, reinforcing the Church’s tendency toward doctrinal rigidity and exclusion. - Integration with Imperial Structures:

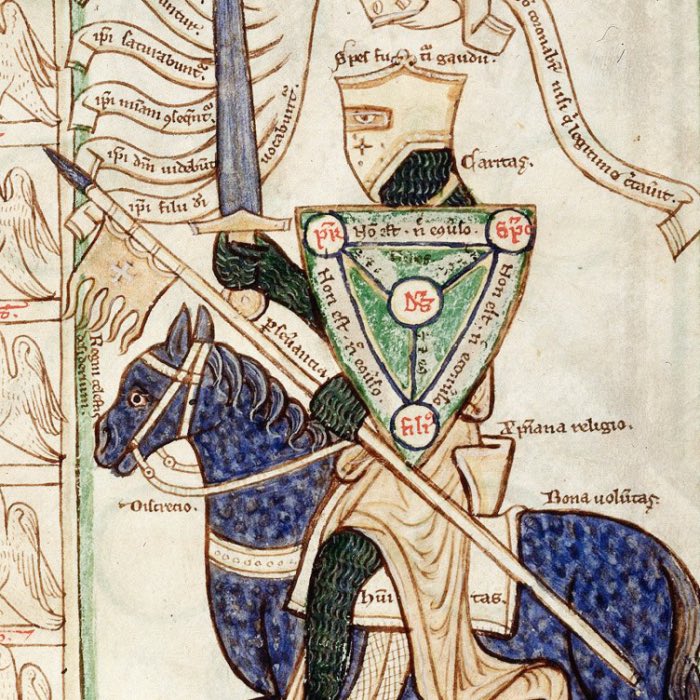

By aligning the papacy with imperial power, Leo introduced a tension between the Church’s spiritual mission and its political ambitions. This integration contributed to the Church’s eventual role as a governing authority, with priorities often at odds with its initial core teachings (resulting in, e.g., the Crusades, the Inquisition, and the persecution of heretics and other marginalized groups).

Conclusion

Leo I’s papacy represents a turning point in the history of Christianity. By asserting the primacy and temporal authority of the Bishop of Rome, Leo established the foundations for the papacy’s enduring claim to universal jurisdiction. His theological framing of Peter and Paul provided a powerful narrative of legitimacy, while his political actions demonstrated the papacy’s capacity to fill the vacuum left by a declining empire.

However, these developments came at a cost. The institutionalization and centralization of the Church under Leo introduced a tension between the hierarchical structures of the Church and the egalitarian ideals of its initial core teachings. This transformation became particularly evident in Leo’s assertive role at the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE), where he not only shaped Christological doctrine but also cemented the authority of the Roman bishop over other patriarchates. Additionally, Leo’s involvement in defining orthodoxy led to the suppression of alternative theological views, such as the Monophysite (e.g., Coptic) and Nestorian (e.g., Assyrian) traditions, further consolidating papal influence at the expense of theological diversity. His insistence on Rome’s primacy over Constantinople and Alexandria set a precedent for later conflicts between the Eastern and Western Churches, ultimately contributing to the schisms that would define medieval Christianity.

Beyond theological disputes, the centralization of the Church in Rome played a decisive role in later historical developments, including the justification for religious wars and persecution. The papal claim to universal authority laid the ideological foundation for the Crusades, which saw mass violence against non-Christians and rival Christian sects alike. Furthermore, the Roman Church, emboldened by its consolidated power, actively engaged in the persecution of Jews, heretics, and other marginalized groups such as women and homosexuals, throughout the medieval period. The Inquisition, the suppression of religious dissent, and the forced conversions under papal directives all stemmed from the structures of authority established during Leo’s time. This tension between hierarchical control and the spiritual origins of Christianity would persist throughout Christian history, shaping debates about the Church’s role in the world and its fidelity to its spiritual mission.

References

- Duffy, Eamon. Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes. Yale University Press, 2006.

- Ullmann, Walter. The Growth of Papal Government in the Middle Ages: A Study in the Ideological Relation of Clerical to Lay Power. Routledge, 2010.

- Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages: 476–752. Routledge, 1979.

- Kelly, J.N.D. The Oxford Dictionary of Popes. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Brown, Peter, The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000, 2013, Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 978-1118301265

comments