The destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria in 391 CE: Christianity’s shift from persecuted to persecutor

The destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria in 391 CE stands as one of the most emblematic events of Late Antiquity, symbolizing the dramatic transformation of Christianity from a persecuted minority to an institution wielding the power of the Roman state. This episode not only marked the decline of pagan religious practices in Alexandria but also reflected the broader social, political, and theological shifts that had accompanied the rise of Christianity as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. The destruction of this magnificent temple dedicated to the Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis offers profound insights into the dynamics of religious conflict, the role of Church authorities, and the consequences of imperial policies aimed at religious consolidation.

The Serapeum as a symbol of paganism

The Serapeum, one of the most splendid temples in the ancient Mediterranean, was central to the religious and cultural life of Alexandria. Dedicated to Serapis, a deity combining Greek and Egyptian elements, the temple represented the syncretic religious traditions that flourished in Hellenistic and Roman Alexandria. Built during the reign of Ptolemy III (246–222 BCE), the Serapeum was not merely a religious site; it was also a symbol of Alexandria’s intellectual and cultural prominence, housing a portion of the famed Library of Alexandria and serving as a center for philosophical and religious discourse.

Map of ancient Alexandria, with the Serapeum located in the south (marked #7). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

By the 4th century, however, the religious landscape of Alexandria had begun to shift. The spread of Christianity, bolstered by imperial support following Constantine’s conversion and the Edict of Milan (313 CE), increasingly challenged the dominance of pagan traditions. While the Serapeum had long been a symbol of paganism’s resilience, its eventual destruction underscored the profound transformation of religious power structures in the Roman Empire.

Victory Pillar, erected by emperor Diocletian in 297 CE, at the Serapeum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Victory Pillar, erected by emperor Diocletian in 297 CE, at the Serapeum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The rise of Christianity and the persecution of paganism

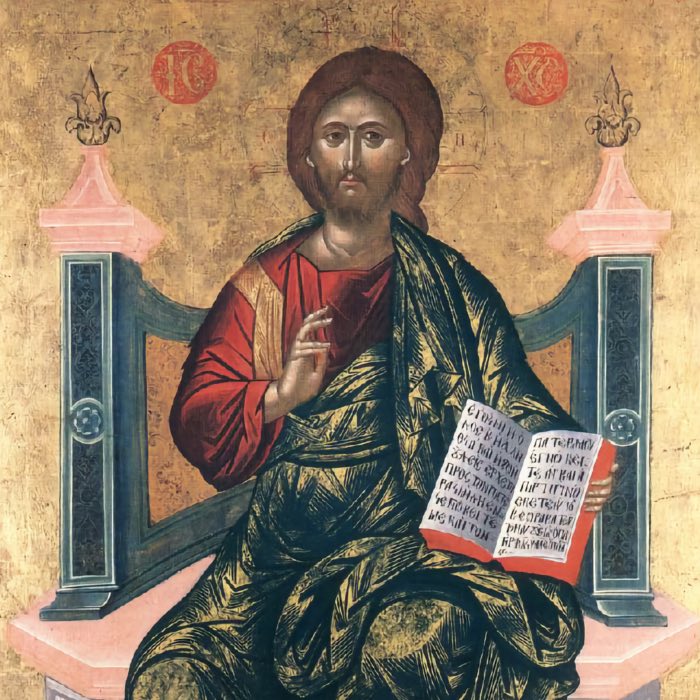

The transformation of Christianity from a persecuted faith to a dominant institution was neither linear nor uncontested. The early Christian community endured centuries of sporadic persecution, often under emperors who viewed the faith as subversive to Roman religious traditions and political stability. This began to change dramatically with Constantine’s rise to power. By granting Christianity legal status and favoring it through imperial patronage, Constantine initiated a process of Christianization that culminated in the reign of Theodosius I (379-395 CE).

Theodosius, often regarded as the first emperor to implement policies of explicit religious exclusivity, issued a series of edicts aimed at eradicating pagan practices. The “Theodosian decrees” banned sacrifices, prohibited the worship of pagan gods, and closed temples throughout the empire. These measures were justified as efforts to secure divine favor for the state but also served to consolidate Christianity’s position as the empire’s official religion. The destruction of the Serapeum occurred within this broader context of religious suppression and imperial intervention.

The destruction of the Serapeum

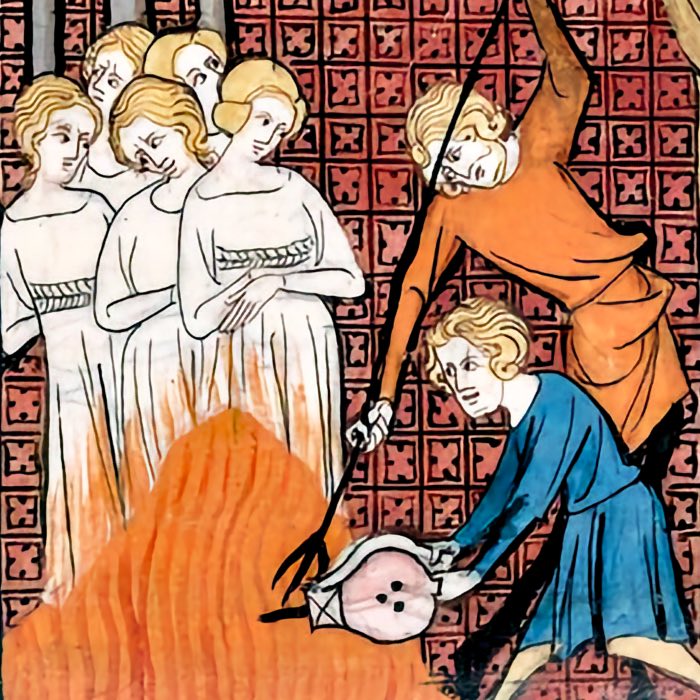

The destruction of the Serapeum was not an isolated event but the culmination of escalating tensions between the Christian and pagan communities of Alexandria. Under the leadership of Bishop Theophilus, the Christian community had grown increasingly assertive in its efforts to challenge pagan practices. Theophilus, who played a central role in the events leading to the Serapeum’s destruction, reportedly desecrated pagan artifacts and converted former temples into Christian churches. These actions provoked fierce resistance from the pagan population, leading to violent confrontations.

In 391 CE, a decree from Theodosius ordered the closure of the Serapeum, along with other pagan temples in Alexandria. Pagan devotees, outraged by this decree and by the desecration of their sacred spaces, fortified themselves within the Serapeum and used the temple as a stronghold. This resistance, however, was short-lived. Imperial troops, supported by local Christian factions, ultimately overwhelmed the defenders, and the Serapeum was destroyed. The temple’s iconic statue of Serapis was smashed, and its ruins became a potent symbol of Christianity’s triumph over paganism.

Remains of the ancient site of the Temple complex of Sarapis at Alexandria. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Remains of the ancient site of the Temple complex of Sarapis at Alexandria. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

The destruction of the Serapeum also had broader implications for the city of Alexandria and for the Roman world. Pagan temples, once centers of civic life and religious devotion, were systematically closed, desecrated, or repurposed for Christian use. This process, often accompanied by acts of violence and coercion, reflected the growing alignment between the Christian Church and imperial power.

The role of Church authorities

The involvement of Church authorities in the destruction of the Serapeum and the broader suppression of paganism underscores the shifting dynamics of religious power in Late Antiquity. Bishops like Theophilus were not merely spiritual leaders but also political actors who played a crucial role in shaping imperial policy and enforcing religious orthodoxy. Theophilus’ actions in Alexandria exemplify the ways in which Church leaders used their influence to marginalize competing religious traditions and consolidate Christian dominance.

The Church’s role in these events also raises questions about the ethical and theological implications of its newfound power. The same institution that had once championed the principles of forgiveness, humility, and nonviolence now found itself complicit in acts of coercion and destruction. This paradox highlights the complexities of Christianity’s transformation from a persecuted faith to an established religion.

From persecuted to persecutor

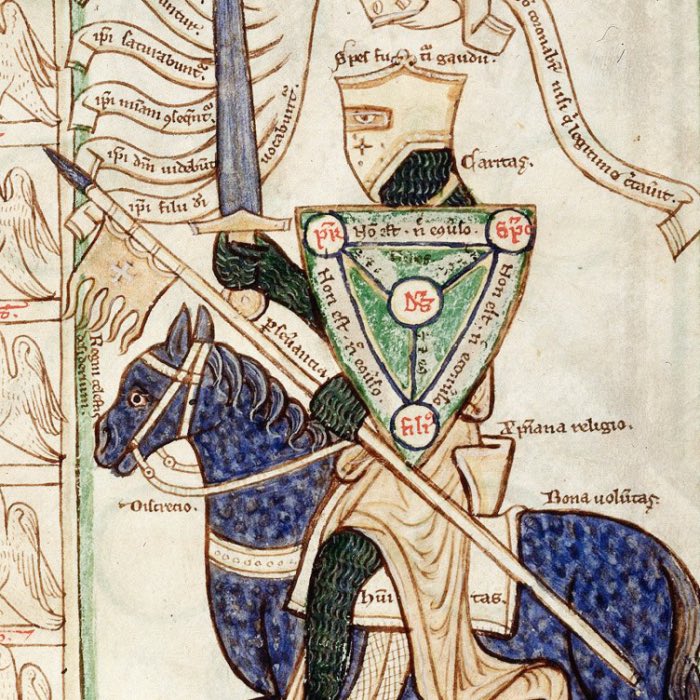

The destruction of the Serapeum serves as a poignant example of Christianity’s transition from a marginalized community to a dominant institution capable of enforcing religious conformity. Once the target of imperial persecution, Christians now wielded the machinery of state power to suppress dissent and eliminate competing religious traditions. This shift was not merely a matter of political expediency but also reflected deeper theological and ideological changes within the Christian Church.

By aligning itself with imperial authority, Christianity gained the means to achieve its vision of religious exclusivity, but it also faced new challenges. The use of violence and coercion to suppress paganism raised questions about the compatibility of these methods with the teachings of Christ. Moreover, the suppression of religious diversity undermined the pluralistic traditions that had characterized much of the Roman world.

Conclusion

The destruction of the Serapeum in 391 CE symbolizes one of the most significant turning points in the history of Christianity and the Roman Empire. It marked the culmination of Christianity’s rise to power and its transformation into an institution capable of enforcing religious orthodoxy. While the destruction of the Serapeum was celebrated by contemporary Christians as a triumph over paganism, it also revealed the darker side of this newfound power — a willingness to use violence and coercion to achieve religious and political goals.

References and further reading

- Thomas Böhm, Peter Bruns, Wolfram Drews, Michael Durst, Michael Fiedrowicz, Johannes Franzkowiak, Reinhard Meßner, Eckhard Wirbelauer, Gerhard Philipp Wolf, Die Geschichte des Christentums – Der lateinische Westen und der byzantinische Osten (431-642), 2005, Herder, Ungekürzte Sonderausgabe, Hrsg.: Norbert Brox, Jean-Marie Mayeur, Charles Piétri, ISBN: 9783451291005

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 2 Die Spätantike, 1996, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499601422

- Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 2000, Penguin Classics, ISBN: 978-0140437645

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, 2010, Penguin, ISBN: 9781101189993

- Trombley, Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370–529, 2001, Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN: 978-0391041219

- Watts, The Final Pagan Generation, 2015, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520283701.

- Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom, 2020, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-0520379220

- MacMullen, Ramsay, Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100-400), 1984, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300032161

- Wilken, Robert Louis, The Christians as the Romans Saw Them, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300098396

comments