The Constantinian Turn: Myth, reality, and its implications for Christianity

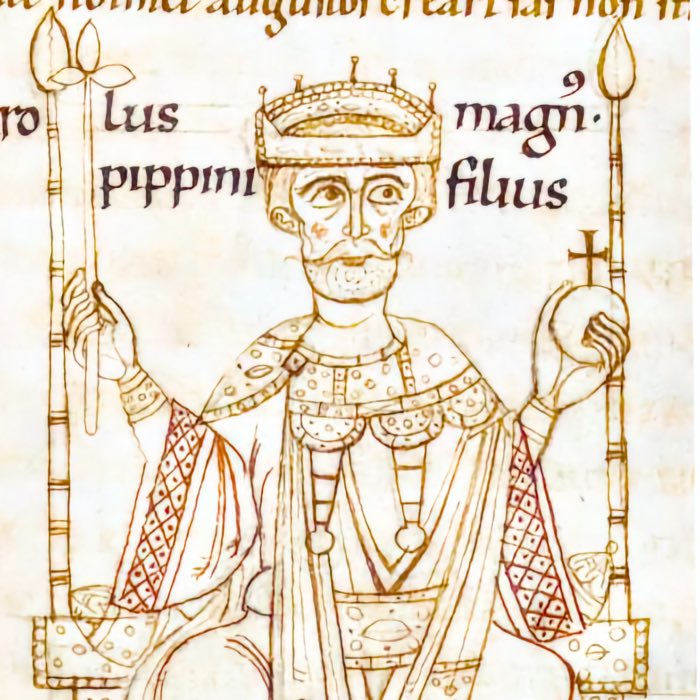

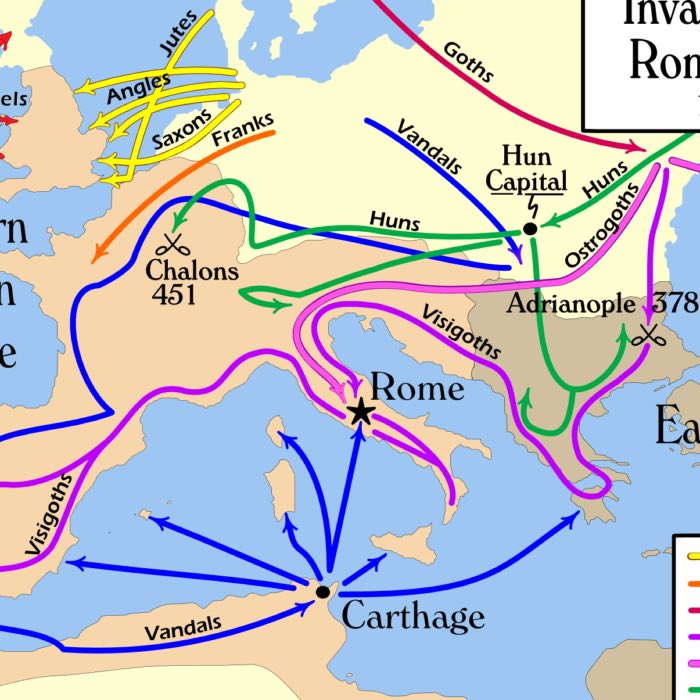

The “Constantinian Turn” refers to the moment when Emperor Constantine the Great supposedly converted to Christianity and ushered in a new era of state-sponsored Christian dominance. This event is often portrayed as the turning point when Christianity transitioned from a persecuted minority religion to the dominant faith of the Roman Empire. However, the historicity of Constantine’s dramatic conversion story — centered on the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312) and his subsequent vision of the cross — has been increasingly scrutinized by modern scholars. In this post, we examine the current state of research regarding the alleged Constantinian Turn, highlighting discrepancies between archaeological evidence and church chronicles. We also explore what this event, whether historically accurate or not, reveals about the Church’s evolution, particularly its association with imperial power, violence, and values that contradict the very core teachings of Christianity.

The Milvian Bridge in Rome today. In 312 CE, at this site there was a pivotal event in the life of Emperor Constantine the Great and the history of Christianity, the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Milvian Bridge in Rome today. In 312 CE, at this site there was a pivotal event in the life of Emperor Constantine the Great and the history of Christianity, the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Constantinian Turn: The traditional narrative

The traditional account of the Constantinian Turn is primarily derived from the writings of Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260–339), a bishop and historian who chronicled Constantine’s reign. According to Eusebius:

- On the eve of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312), Constantine experienced a vision of the cross accompanied by the words In hoc signo vinces (“In this sign, you will conquer”).

- Inspired by this divine sign, Constantine adopted the Christian God as his protector and led his army to victory.

- Following this victory, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313, granting religious tolerance to Christians and marking the beginning of their privileged status within the empire.

From this point forward, the narrative suggests, Christianity transformed into a state religion, culminating in its declaration as the official religion of the empire under Emperor Theodosius in 380.

The Battle of Milvian Bridge, 1520-1524, part of a large fresco, Vatican City, Apostolic Palace. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The Battle of Milvian Bridge, 1520-1524, part of a large fresco, Vatican City, Apostolic Palace. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The state of modern research: Myth vs. reality

While the Constantinian Turn remains a cornerstone of Christian historiography, recent research has called into question the accuracy and completeness of this narrative.

Discrepancies in the conversion story

The vision of the cross

The vision of the cross, as described by Eusebius, is absent from earlier accounts, including Lactantius, another contemporary chronicler. Lactantius instead recounts a simpler dream in which Constantine was instructed to mark his soldiers’ shields with the Christian symbol (likely the Chi-Rho).

Archaeological evidence does not confirm widespread use of Christian symbols by Constantine’s army at the time of the battle, suggesting that the vision story may have been embellished or entirely fabricated by later Christian apologists.

Constantine’s religious practices

Constantine continued to honor pagan gods, particularly Sol Invictus (the Unconquered Sun), throughout much of his reign. Coins minted during this period prominently featured pagan imagery, raising doubts about the sincerity or exclusivity of his Christian faith. This duality suggests that Constantine’s policies may have been motivated by pragmatism, seeking to unify a diverse empire through religious inclusivity rather than personal piety.

Left: A coin struck in 313, depicting Constantine as the companion of Sol Invictus. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Silver medallion of 315; Constantine with a chi-rho symbol as the crest of his helmet. While Constantine continued to honor pagan gods, he also adopted Christian symbols in his iconography. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Constantine was only baptized on his deathbed in 337, a common practice among Roman elites who believed in the purification of sins through last-minute baptism. This delay complicates the narrative of a sudden and transformative conversion, further supporting the notion that his alignment with Christianity was strategic and political rather than purely theological.

Archaeological evidence

There is limited archaeological evidence to suggest an immediate or dramatic shift in imperial policy or public religious life following the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Christianity’s rise to dominance appears to have been gradual, as evidenced by the continued presence of pagan temples, inscriptions, and public rituals for decades. For instance, key cities like Rome and Constantinople maintained active pagan sanctuaries, and many imperial coins minted during this period still bore pagan symbols. Additionally, Christian churches were often built adjacent to or even on top of pagan temples, symbolizing a slow and symbolic transition rather than a wholesale replacement.

Arch of Constantine in Rome. After the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the Roman Senate to commemorate Constantine’s victory over Maxentius in 312. While it contains many reliefs and inscriptions about the events, there is no explicit Christian symbolism at this site. In contrary, Roman gods are depicted. Also the soldier depicted lacks Christian symbols, unlike described in the narrative of Eusebius. Source top: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0), source bottom left: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5), source bottom right: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Arch of Constantine in Rome. After the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the Roman Senate to commemorate Constantine’s victory over Maxentius in 312. While it contains many reliefs and inscriptions about the events, there is no explicit Christian symbolism at this site. In contrary, Roman gods are depicted. Also the soldier depicted lacks Christian symbols, unlike described in the narrative of Eusebius. Source top: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0), source bottom left: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5), source bottom right: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The role of Eusebius

Eusebius’ account of Constantine’s conversion is highly hagiographical, portraying the emperor as a divinely chosen ruler and downplaying his continued involvement in pagan practices. Modern scholars argue that Eusebius likely crafted this narrative to legitimize Constantine’s authority and the privileged status of the Church, rather than provide an objective historical account.

Constantine’s self-understanding

Roman emperors, including Constantine, were often perceived as semi-divine figures during their lifetimes, a legacy of imperial ideology that merged political power with religious authority. This tradition, deeply rooted in Roman culture, provided emperors with an aura of sacred legitimacy. Constantine’s self-presentation must be viewed within this context, where he might have seen his role as both a temporal ruler and a divinely chosen intermediary.

Constantine and Sol Invictus

Before his alleged conversion to Christianity, Constantine was an ardent devotee of Sol Invictus, the Unconquered Sun, a deity associated with light, victory, and universal order. Coins minted during his early reign frequently depicted Sol Invictus, symbolizing divine favor and imperial authority. Even after his victory at the Milvian Bridge, Constantine continued to employ solar imagery in his public iconography, including the famous column in Constantinople, where his statue portrayed him with radiating sun rays, a clear reference to Sol Invictus.

Constantine the Great (306-337) as Sol Invictus. Struck ca. 309-310 in Lugdunum. Sol standing facing right, right hand raised, the globe in his left. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Constantine the Great (306-337) as Sol Invictus. Struck ca. 309-310 in Lugdunum. Sol standing facing right, right hand raised, the globe in his left. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

This persistent association raises critical questions: Did Constantine equate Sol Invictus with the Christian god? Or did he see Christ as a continuation or fulfillment of solar divinity? Some scholars argue that Constantine’s identification with Sol Invictus allowed him to bridge the religious divide in his empire, appealing simultaneously to pagan and Christian audiences. This syncretic approach would have been politically advantageous, ensuring stability during a period of profound religious transformation.

Did Constantine see himself as Christ?

The notion of Constantine perceiving himself as Christ-like, or even as Christ’s earthly representative, has been a subject of scholarly debate. Eusebius of Caesarea’s writings often present Constantine in messianic terms, portraying him as a divinely chosen instrument of God’s will. For many of his Christian contemporaries, Constantine’s victories and patronage of the Church positioned him as a savior figure, echoing aspects of Christ’s role in salvation history.

However, Constantine’s self-image might have been more pragmatic than theological. As emperor, he inherited a Roman tradition of divine rulership, where the emperor served as a visible manifestation of divine order. This status likely influenced his approach to Christianity, where he could integrate his imperial identity with the emerging faith, positioning himself as a universal ruler under a universal god YHWH.

Perceptions of divinity among contemporaries

For pagans, Constantine’s ongoing use of Sol Invictus imagery and his reluctance to fully renounce traditional Roman religious practices may have reinforced his image as a divine emperor in the classical sense. For Christians, however, his patronage of the faith and his role in convening the Council of Nicaea (325) elevated his status to near-apostolic levels. While he stopped short of declaring himself divine in Christian terms, Constantine’s actions blurred the lines between imperial and ecclesiastical authority, setting a precedent for the fusion of Church and state.

Constantine’s conversion: A pragmatic faith?

Constantine’s delayed baptism, occurring only on his deathbed, complicates the narrative of his genuine Christian faith. This hesitation might reflect a strategic approach to religion, where Constantine maintained a balancing act between Christian and pagan constituencies. It also suggests that his “conversion” was less about personal piety and more about the practicalities of governance, using religious symbolism to unify a diverse empire.

Constantine with his mother Helena and the relic she discovered of the alleged Holy Cross, icon, 16th century. It is said, that Constantine’s mother Helena, who was a Christian, discovered the True Cross in Jerusalem. She cut the cross into several pieces and distributed them to churches in the empire, where they served as relics for veneration. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Constantine with his mother Helena and the relic she discovered of the alleged Holy Cross, icon, 16th century. It is said, that Constantine’s mother Helena, who was a Christian, discovered the True Cross in Jerusalem. She cut the cross into several pieces and distributed them to churches in the empire, where they served as relics for veneration. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

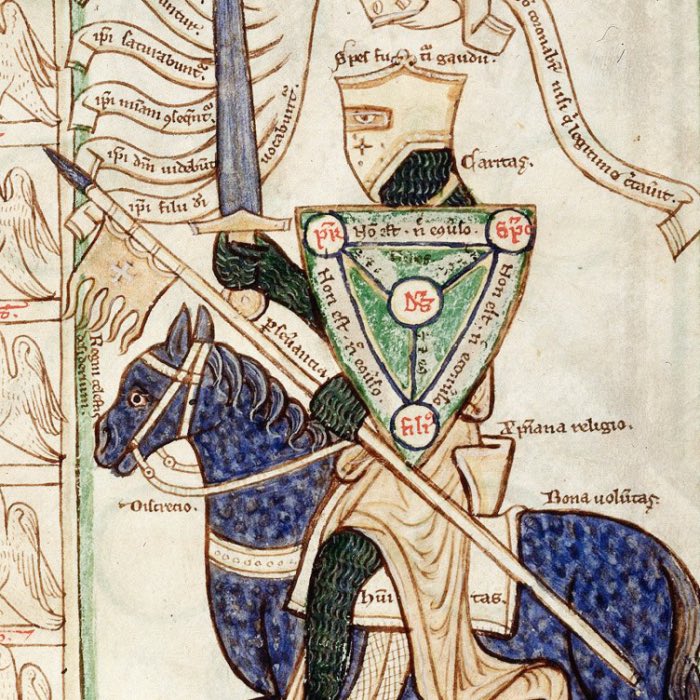

The implications of the Constantinian Turn

The ‘triumph’ of Christianity through violence

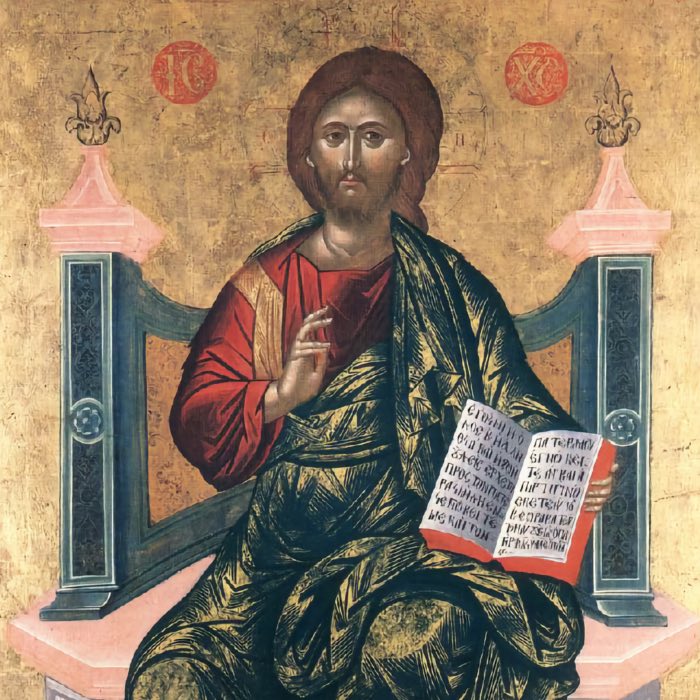

Whether the story of Constantine’s divine vision is historical or legendary, it raises troubling questions about the association of Christianity with military conquest. The triumph of the Church, as framed by Eusebius, is inseparable from Constantine’s violent victory at the Milvian Bridge. This alignment with imperial power and warfare contrasts starkly with Jesus’ teachings of non-violence, humility, and love for one’s enemies (e.g., Matthew 5:38–44).

The Church’s foundation on a battle — real or symbolic — marked a departure from its origins as a grassroots movement rooted in compassion and service. It introduced an enduring tension between the teachings of Jesus and the realities of institutional power.

Fusion of imperial and ecclesiastical authority

Constantine’s self-understanding and his blending of imperial and religious authority had profound implications for Christianity. By aligning the faith with his imperial image, he set the stage for the Church’s transformation into a hierarchical institution modeled on Roman political structures. The emperor’s perceived divinity further entrenched the idea of centralized authority, a concept that would shape the Church’s development for centuries.

This merging of imperial and ecclesiastical power represented a significant departure from the egalitarian and service-oriented ethos of Jesus’ teachings. While it ensured Christianity’s survival and growth, it also introduced tensions that would challenge the Church’s ability to remain true to its spiritual roots. Constantine’s dual role as emperor and Christian patron highlights the complexities of this pivotal moment in history, where the faith of the persecuted became the faith of the empire.

The aftermath of the Constantinian Turn

The Constantinian Turn had far-reaching consequences for the development of Christianity and its relationship with the Roman Empire:

Christianity’s integration into the Roman Empire

Following Constantine’s reign, Christianity became increasingly intertwined with imperial politics and culture. Imperial patronage played a significant role in this transformation. Constantine himself funded the construction of grand churches, such as St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, which elevated Christian worship spaces above their humble origins in house churches. This shift not only provided Christians with more prominent places of worship but also symbolized the newfound status and legitimacy of the faith within the empire.

Additionally, clerical privileges were expanded during this period. Bishops were granted judicial and administrative authority, aligning the Church hierarchy with the imperial bureaucracy. This integration of ecclesiastical and state functions further solidified the Church’s influence and power within the Roman Empire.

The suppression of paganism also marked this era. While Constantine did not outright ban pagan practices, his successors enacted policies that marginalized and eventually prohibited them. Theodosius I, who reigned from 379 to 395, declared Christianity the official religion of the empire and criminalized pagan rituals. This decisive move marked the culmination of Christianity’s rise to dominance and the decline of traditional Roman religious practices.

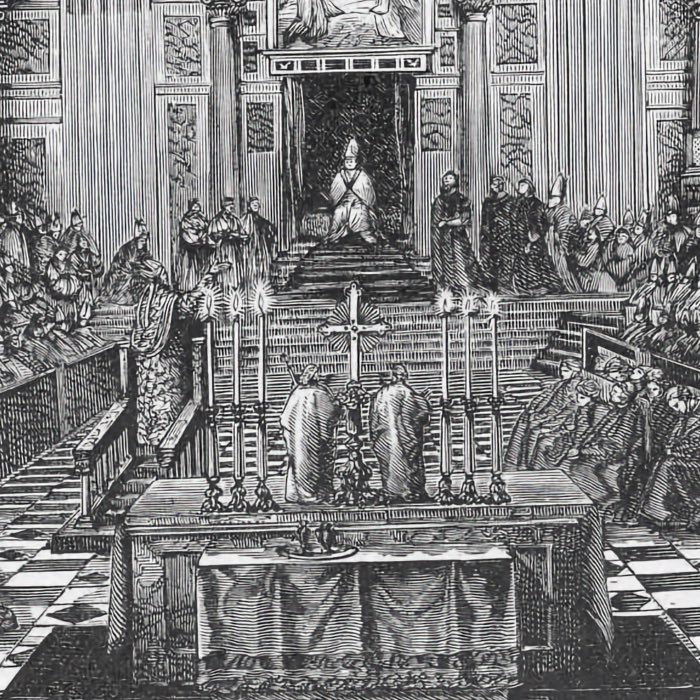

The rise of hierarchical structures

The integration of Christianity into the imperial framework significantly accelerated the development of hierarchical Church structures. Bishops, particularly those in major cities such as Rome, Alexandria, and Constantinople, gained substantial political and spiritual authority. Their influence extended beyond religious matters, often intersecting with imperial politics and governance.

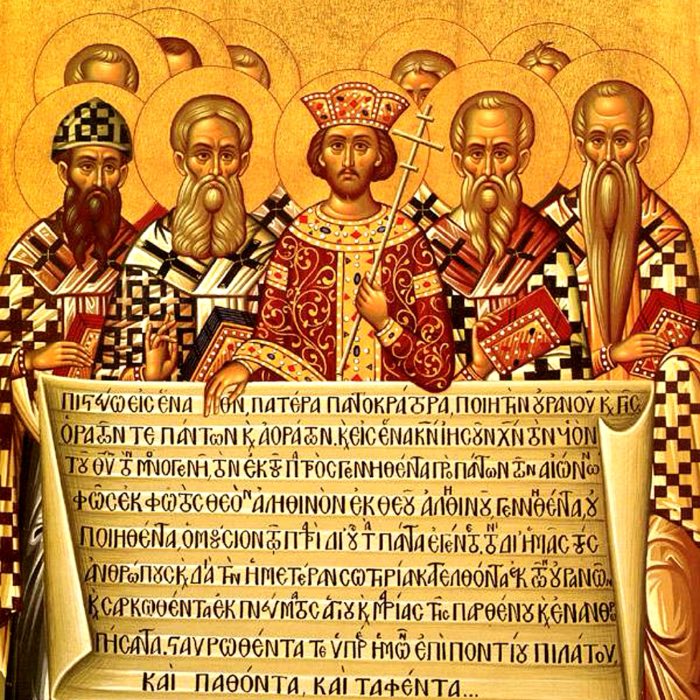

Councils, such as the First Council of Nicaea in 325, played a crucial role in this hierarchical development. These gatherings of Church leaders established creeds and doctrines that solidified the Church’s institutional identity. The Nicene Creed, formulated during this council, became a foundational statement of Christian orthodoxy. However, this process of doctrinal consolidation also had the effect of suppressing theological diversity. Debates and differing interpretations that had previously been tolerated within the Christian community were now increasingly viewed as heretical and subject to condemnation.

The establishment of these hierarchical structures and the enforcement of uniform doctrines marked a significant transformation in the nature of the Church. It evolved from a loosely organized network of communities into a centralized institution with defined leadership and authoritative teachings. This shift not only strengthened the Church’s position within the Roman Empire but also laid the groundwork for its enduring influence in the centuries to come.

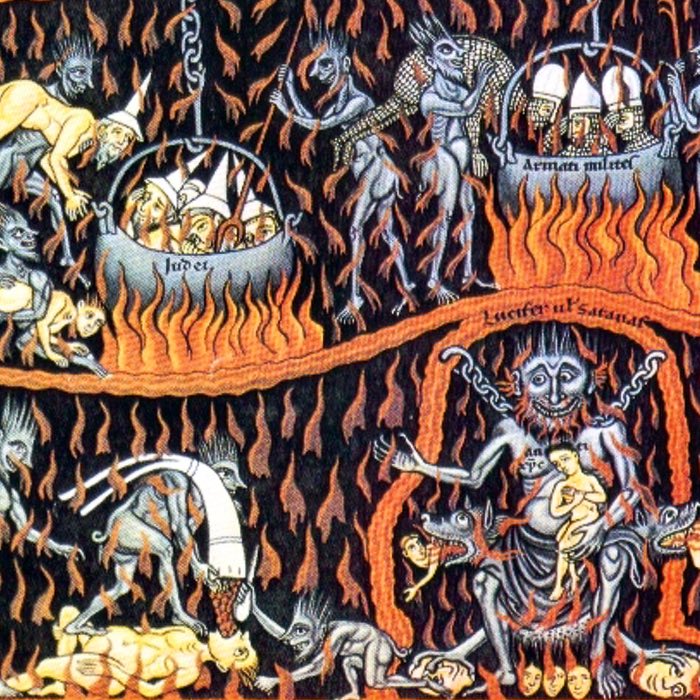

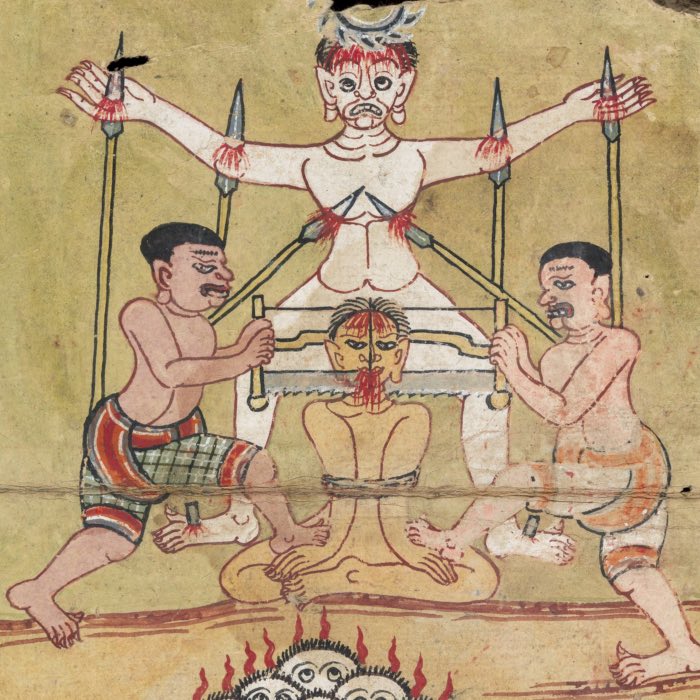

Internal persecution

The Church, once a persecuted minority, began to persecute dissenters within its own ranks. Heresies such as Arianism were condemned, and their followers faced excommunication or exile. Theological debates, previously tolerated as part of Christianity’s diversity, became matters of imperial policy, enforced with the weight of the state.

Conclusion

The Constantinian Turn, whether historical or largely mythological, represents a pivotal moment in the history of Christianity. It marked the transition of the faith from a marginalized movement to an imperial institution, but it also introduced profound contradictions. The Church’s alignment with imperial power and violence, as symbolized by Constantine’s victory, stood in tension with the teaching of Christianity’s self-proclaimed founder, Jesus Christ, who advocated for peace, humility, and a rejection of worldly power.

This alignment had lasting consequences. Christianity’s integration into the Roman Empire facilitated its spread and institutional stability, but it also led to the suppression of dissent, the erosion of its ethical ideals, and the marginalization of its original message. As such, the Constantinian Turn marks a critical juncture in the evolution of the Church, where the pursuit of power and influence came at the cost of its spiritual integrity.

References and further reading

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, 2010, Penguin, ISBN: 9781101189993

- Drake, H.A., Constantine and the bishops: the politics of intolerance, 1999, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN: 978-0801862182

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Life of Constantine, 2023, Dalcassian Publishing Company, ISBN: 978-1088165430

- Lenski, Noel, The Cambridge companion to the age of Constantine, 2012, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1107601109

- Mitchell, Stephen, A history of the later Roman Empire, CE 284–641: the transformation of the ancient world, 2006, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, ISBN: 978-1405108560

- Bardill, Jonathan, Constantine, divine emperor of the Christian golden age, 2015, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1107538986

- Jones, A.H.M., Constantine and the conversion of Europe, 2007, Jones Press, ISBN: 978-1406760118

- Brown, Peter, The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000, 2013, Wiley & Sons, ISBN: 978-1118301265

- Gaddis, Michael, There is no crime for those who have Christ: religious violence in the Christian Roman Empire, 2015, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520286245

- Holloway, R. Ross, The archaeology of early Rome and Latium, 1996, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415143608

- Wilken, Robert Louis, The first thousand years: a global history of Christianity, 2012, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300118841

- Louth, Andrew, Greek East and Latin West: the Church CE 681–1071, 2007, St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, ISBN: 978-0881413205

- Markus, Robert A., Christianity in the Roman world, 1975, Thames & Hudson Ltd, ISBN: 978-0500830017

- Curran, John, Pagan city and Christian capital: Rome in the fourth century, 2002, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199254200

- Sauer, Eberhard W., The archaeology of religious hatred in the Roman and early medieval world, 2009, TemThe History Press, ISBN: 978-0752425306

comments