Theosis: An alternative view of hell, evil, and salvation in Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodox Christianity presents a unique theological perspective that diverges in significant ways from Western Christian traditions. Among these differences are the understanding of hell, evil, and the ultimate purpose of human life. While the Western Church often conceptualizes hell as a place of punitive suffering and views salvation as a juridical resolution to sin, Eastern Orthodoxy frames these ideas within a more relational and mystical context, emphasizing theosis — the union of humanity with the divine. In this post, we explore these theological differences by focusing on the Orthodox views of hell, evil, and the concept of theosis as an transformative process.

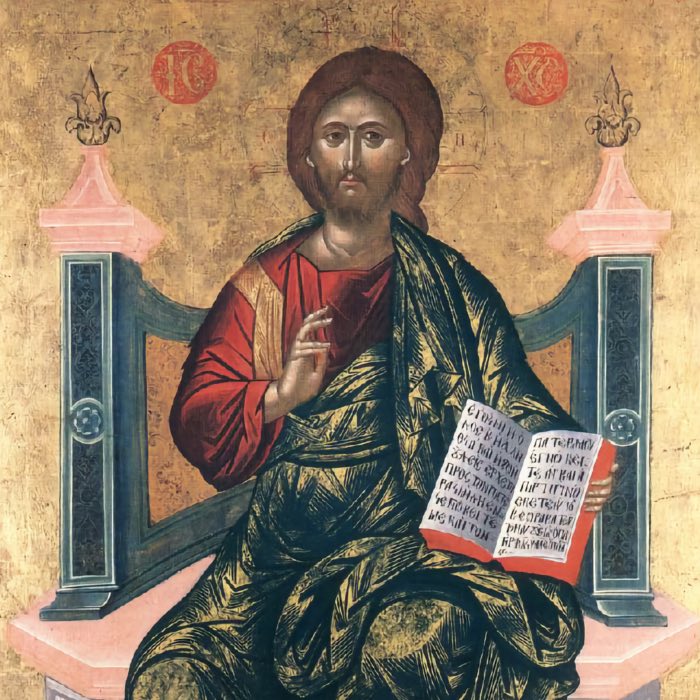

![]()

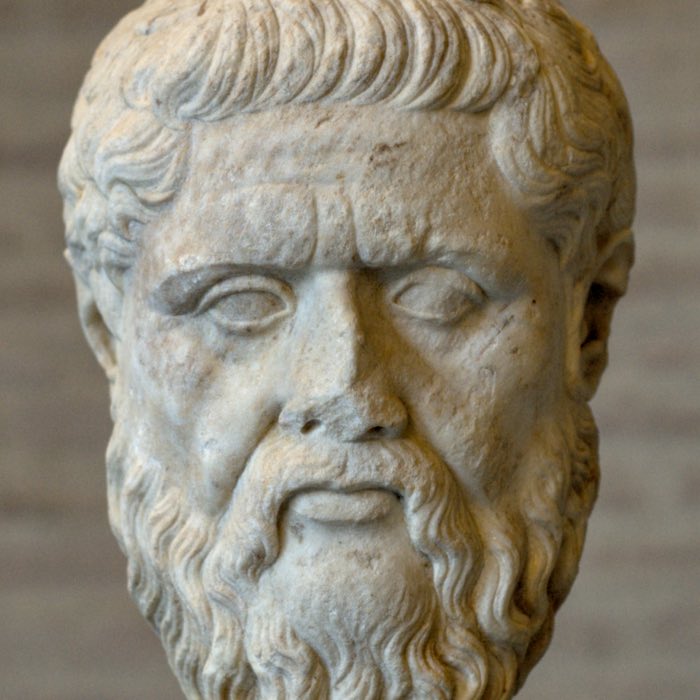

Icon showing the Transfiguration of Christ, part of an iconostasis in Constantinople style, middle of the 12th century. The Transfiguration is a significant event in the narrative of Jesus, where he became radiant in glory upon a mountain, three of his apostles, Peter, James, and John, who witnessed the event. Then the Old Testament figures Moses and Elijah appear, and Jesus speaks with them. Both figures had eschatological roles: they symbolize the Law and the prophets, respectively. Jesus is then called “Son” by the voice of YHWH. The motif of the Transfiguration in Eastern Orthodox theology symbolizes the revelation of divine light and the potential for human participation in divine life, which ties to the concept of theosis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Orthodox understanding of hell: An existential condition

In Western Christianity, heavily influenced by Augustine and later scholastic theology, hell has often been described as a place of eternal punishment for sinners, imposed by divine justice. The Eastern Orthodox tradition, however, reframes hell not as a geographical location or divine retribution but as an existential condition — the experience of God’s presence by those who are estranged from Him. This perspective is rooted in the Orthodox understanding of God as omnipresent and unchanging.

For the Orthodox, hell and heaven are not separate locations but different responses to the same reality: the presence of God. As St. Isaac the Syrian wrote:

It is wrong to think that sinners in hell are cut off from God. The love of God is unbearable torment for those who have not acquired it within themselves.

In this framework, hell is not the absence of God’s presence but the inability to participate in His love. It is a self-chosen state of alienation, where the unrepentant soul experiences divine light as painful rather than joyous.

This understanding has profound implications for how Orthodox Christians view sin, repentance, and salvation. Rather than focusing on punishment, the Orthodox Church emphasizes the “healing of the soul” and the “restoration of the person” to communion with God. Hell, in this sense, is the natural consequence of a life lived in rejection of divine love.

Theosis: The ultimate goal of human life

Central to Eastern Orthodox theology is the concept of theosis, often translated as “divinization” or “deification”. This doctrine teaches that the ultimate purpose of human life is to become united with God, partaking in His divine nature while remaining distinct as created beings. This idea is deeply rooted in Scripture, particularly in 2 Peter 1:4, which speaks of becoming “partakers of the divine nature”.

A process of transformation

Theosis is not merely a future hope but an ongoing process that begins in this life. Through participation in the sacraments, prayer, ascetic practices, and the cultivation of virtue, the believer is gradually transformed into the likeness of Christ. Unlike the Western emphasis on justification as a legal declaration, Orthodoxy views salvation as a dynamic and relational process of healing and restoration.

Salvation

Theosis also reframes the purpose of Christ’s incarnation. According to St. Athanasius of Alexandria:

God became man so that man might become God.

This statement encapsulates the Orthodox view that Christ’s life, death, and resurrection were not only about atoning for sin but also about enabling humanity to achieve its original purpose: union with the divine. This transformative vision of salvation is fundamentally positive, focusing on the elevation of human nature rather than its condemnation.

Origins of theosis

Jewish roots

The concept of theosis has its roots in both biblical and patristic traditions. In the Scriptures, the foundational idea of humanity’s participation in the divine nature can be found not only in 2 Peter 1:4 but also in Genesis, where humanity is described as being made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26). The early Church Fathers expanded on these scriptural themes, particularly those of the Eastern tradition, such as St. Irenaeus of Lyon, who emphasized that the incarnation of Christ restores the image of God in humanity.

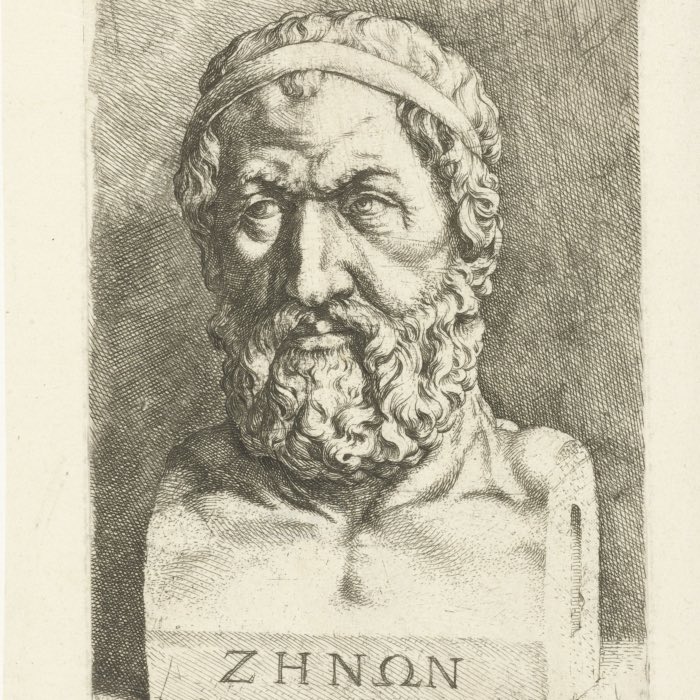

Origins in classical Greek philosophy

The concept of theosis has clear roots and parallels in Greek philosophy, particularly within Platonism and Neoplatonism. While theosis is distinctively Christian in its theological framework, many of its foundational ideas can be traced to earlier Greek philosophical traditions.

Platonic Philosophy: Participation in the Good

In Plato’s works, particularly in The Republic and Timaeus, there is a strong emphasis on the ultimate Good as the source of all existence and truth. Plato’s theory of forms posits that all things participate in the ideal forms, with the Form of the Good being the highest and most perfect. Human beings, through philosophical contemplation and moral living, could ascend toward the Good, achieving a kind of spiritual fulfillment.

This Platonic idea of “participation” resonates with the Christian concept of theosis, where humans are called to partake in the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4). Plato’s vision of an ascent toward the ultimate Good inspired later philosophical and theological traditions that saw humanity’s purpose as transcending the material world and achieving union with the divine.

Aristotle: Teleology and fulfillment of potential

Aristotle introduced the idea of telos (purpose or end goal) as central to understanding human nature. For Aristotle, every being has a purpose, and fulfillment of that purpose leads to eudaimonia (flourishing or happiness). In humans, this purpose involves the actualization of reason and the cultivation of virtue, aligning oneself with the highest truths.

Although Aristotle did not explicitly propose theosis, the idea of humans reaching their ultimate purpose influenced later Christian thinkers, who saw the fulfillment of human potential as participating in God’s divine life. The synthesis of Aristotle’s teleology with Christian thought shaped how theologians framed humanity’s ultimate purpose as union with God.

Stoicism: Unity with the Divine Logos

The Stoics utilized the concept of logos, a rational principle that pervades and orders the universe. For the Stoics, living in accordance with the logos was the highest moral and spiritual goal, bringing one into harmony with the divine rationality of the cosmos. This idea of aligning oneself with a divine principle provided a framework that early Christian theologians adapted to their understanding of union with Christ, who is identified as the Logos in the Gospel of John.

Neoplatonism: Ascent to the One

Neoplatonism, as developed by Plotinus, provided a fully articulated framework for spiritual ascent. Plotinus described the human soul’s journey of returning to its source, the One, through stages of purification, contemplation, and unity. For Plotinus, the One was the ultimate source of all being, and achieving union with it was the highest human goal. This process required transcending the material world and aligning oneself with the divine.

Christian theologians such as the Cappadocian Fathers and St. Maximus the Confessor adapted this framework to explain the Christian understanding of theosis. However, unlike the Neoplatonic idea of union with the One as an impersonal source, Christian theosis emphasizes a personal relationship with God, made possible through the incarnation of Christ and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

Adaptations by the Early Church Fathers

In summary, Greek philosophy, particularly in the Platonic and Neoplatonic traditions, introduced the idea of an ascent or return to the divine source (the One). Central to this was the concept that:

- Human beings have a divine aspect (the rational soul, for example) that connects them to the higher realities.

- The goal of life is to transcend the material world and align oneself with the divine, whether it is Plato’s Form of the Good, Aristotle’s nous (intellect), or Plotinus’s One.

- This process involves purification and contemplation, as the soul must free itself from the distractions and impurities of the material realm to achieve this union.

While these ideas were later embraced and reinterpreted by Christian theologians, their origin is unequivocally Greek. The Jewish tradition, in contrast, lacks this framework. In Judaism, the worshipped god YHWH is wholly other, transcendent, and distinct from humanity. The covenantal relationship with YHWH is focused on obedience, worship, and ethical conduct rather than an ontological union with the divine. The radical idea that humanity could partake in God’s nature did not exist in early Jewish theology.

When Christianity emerged, its theological development was heavily influenced by Hellenistic culture. The early Church Fathers, especially those in the East, found in Greek philosophy a language and framework to articulate Christian doctrines, including theosis. However, they adapted the Greek idea in significant ways:

- The Incarnation: Unlike Greek philosophy, where the ascent to the divine is achieved through contemplation and intellectual effort, Christian theosis is grounded in the Incarnation. YHWH becomes man in Jesus Christ so that humanity can become divine. This is encapsulated in St. Athanasius’s famous statement “God became man so that man might become God.”.

- Grace over effort: While Greek philosophy often emphasized the individual’s effort in attaining union with the divine (through virtue, reason, or contemplation), Christian theosis depends on divine grace. Theosis is not earned but is a gift, made possible through Christ and the Holy Spirit.

- Personal god: The Greek philosophical notion of union with the divine often involved merging with an impersonal source (e.g., the One in Neoplatonism). In Christianity, theosis involves a personal relationship with the Jewish triune god YHWH, emphasizing love, communion, and reciprocity rather than mere absorption into a transcendent principle.

Thus, while the Christian concept of theosis is heavily indebted to Greek philosophy, its adaptation within a Jewish-Christian framework introduced key theological differences:

- Monotheism: The Jewish-Christian belief in a singular, personal god, YHWH, fundamentally redefined the idea of union. Instead of participating in a universal, impersonal principle, Christians participate in the life of a personal god through Christ and the Spirit.

- Historical context: Theosis in Christianity is tied to the narrated events of Jesus’s biography. Greek philosophy, in contrast, is more abstract and metaphysical, detached from historical narratives.

- Communal aspect: Christian theosis often emphasizes the communal nature of salvation through the Church, while Greek philosophy tends to focus on individual ascent.

Evil as the absence of good

A key element of Orthodox theology is its understanding of evil. Drawing on the writings of early Church Fathers like St. Basil the Great and St. Gregory of Nyssa, Orthodox Christianity teaches that evil is not a substance or independent force but a privation of good. This idea aligns with the philosophical insights of Neoplatonism, which profoundly influenced early Christian thought.

Evil, in this view, has no existence of its own. It arises when created beings turn away from God, the source of all goodness. Just as darkness is the absence of light, evil is the absence of good. This perspective underscores the Orthodox belief in the inherent goodness of creation. Even in their fallen state, human beings and the world retain the potential for restoration and transformation.

This understanding of evil also shapes the Orthodox approach to sin and morality. Sin is not primarily viewed as the violation of divine law but as a condition of brokenness and estrangement from God. Consequently, the Church’s pastoral focus is not on punishment but on healing and reconciliation. The sacrament of confession, for example, is understood as a therapeutic act that restores the soul’s relationship with God.

Origins of the concept

The understanding of evil as the absence of good has roots in various ancient intellectual traditions that predate and influence Christian theology:

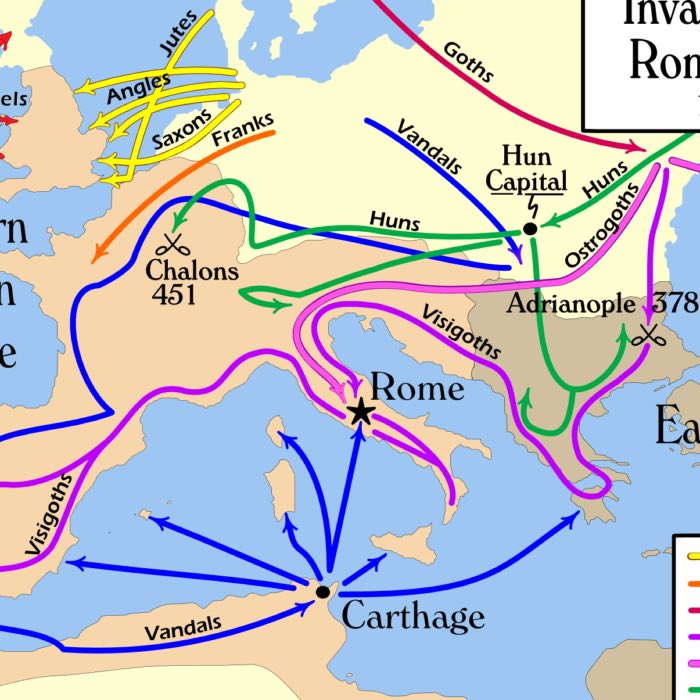

Mesopotamian and Egyptian traditions

In these ancient cultures, the concept of evil was often tied to the struggle between order and chaos. In Mesopotamian cosmology, deities like Marduk represented order, while chaotic forces such as Tiamat embodied disorder and destruction. Similarly, in Egyptian thought, the principle of Ma’at (cosmic order and justice) stood in opposition to Isfet (chaos and injustice). While these frameworks did not explicitly define evil as a privation, their focus on maintaining divine order as the source of good contributed to later theological developments, including the Christian understanding of evil as disorder or separation from God’s will.

Judaism

The Hebrew Bible does not explicitly frame evil as the absence of good, but its monotheistic worldview lays the groundwork for this understanding. In Genesis, creation is repeatedly described as “good”, emphasizing that everything originates from God’s goodness. Evil arises in the biblical narrative when humans misuse their free will, as seen in the story of the Fall. Later rabbinic thought, particularly in dialogue with Hellenistic philosophy, began to explore the idea of evil as the absence or negation of divine goodness.

Neoplatonism

Greek thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle significantly influenced the Christian conception of evil. Plato, especially in works like the Republic, suggested that evil results from ignorance and a lack of alignment with the ultimate Good (the Form of the Good). Aristotle expanded on this by emphasizing teleology — the idea that all things aim toward their inherent purpose (telos). When something fails to fulfill its purpose, it can be considered deficient or “evil”, though not in the sense of an independent force.

Plotinus, a key figure in Neoplatonism, explicitly articulated that evil is a privation of the good. For Plotinus, everything emanates from the One, the ultimate source of all existence and goodness. Evil occurs when beings turn away from this source, resulting in a lack of harmony and order (called in Latin: privatio boni, the privation of the good). This idea was revolutionary in its rejection of dualistic frameworks that portrayed good and evil as opposing, co-equal forces (a perspective more common in certain Gnostic and Zoroastrian traditions).

This idea profoundly influenced early Christian thinkers, particularly Augustine, who adapted it to a Christian framework, emphasizing that evil is not a created substance but the absence or corruption of God’s goodness — a turning away from God, who is the source of all goodness.

This adaptation allowed Augustine to address questions about the origin of evil without attributing its creation to God, preserving the belief in a wholly good and omnipotent deity. It also reinforced a key Christian message: evil is not a competing divine power but the result of free will misused by creatures turning away from God.

So while the privatio boni concept has become deeply embedded in Christian theology, its intellectual origins are undeniably Neoplatonic. This demonstrates how early Christian thinkers like Augustine synthesized existing philosophical traditions with Christian doctrine to create a cohesive theological framework. It also highlights how Christianity has historically interacted with and absorbed ideas from surrounding cultural and intellectual contexts.

Divergences between Eastern and Western Christianity

The differences between Eastern and Western Christian thought on hell, theosis, and evil are rooted in broader theological and philosophical divergences. Western Christianity, particularly after Augustine, developed a more juridical framework for understanding sin and salvation. This perspective emphasizes guilt, punishment, and the satisfaction of divine justice. In contrast, Eastern Orthodoxy adopts a more relational and mystical approach, emphasizing the restoration of communion with YHWH.

These differences are not merely theological abstractions but have practical implications for how Christians live out their faith. In the West, the focus on avoiding hell and achieving heaven often shapes religious practices and moral behavior. In the East, the emphasis on theosis encourages a holistic and transformative spirituality aimed at union with YHWH. This distinction reflects differing understandings of the human condition and the purpose of salvation.

Conclusion

Eastern Orthodox Christianity offers a profoundly relational and mystical vision of human destiny. Its understanding of hell as an existential condition, its emphasis on theosis as the ultimate goal of life, and its view of evil as the absence of good present a cohesive and transformative theological framework. These ideas challenge the punitive and juridical models prevalent in much of Western Christianity, offering instead a vision of salvation as healing, restoration, and union with the divine. In this framework, hell is not a divine punishment but the tragic result of a self-chosen alienation from God’s love.

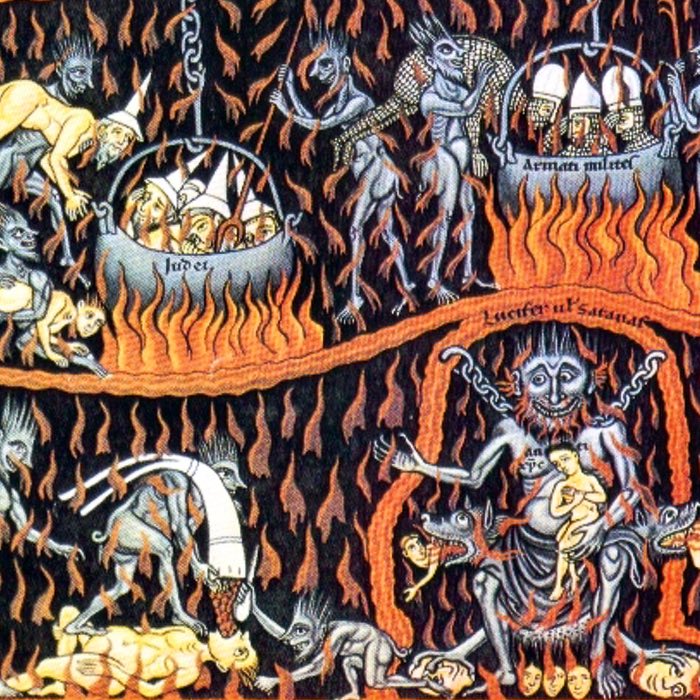

The ultimate hope of Orthodoxy lies in theosis — the transformative journey toward becoming partakers of the divine nature. This profound difference in theological focus between the Eastern and Western Churches has far-reaching implications, not only for spiritual practice but also for how individuals perceive and engage with the world and their place in time. While Western Christianity’s juridical emphasis on sin and redemption may foster a worldview steeped in guilt, duty, and divine judgment, introducing a dualistic worldview, differentiating between good and evil, Eastern Orthodoxy’s focus on theosis encourages a mindset that is relational and transformational, centering on the restoration of harmony with the divine and creation. This distinction likely influenced broader cultural attitudes, shaping different ways of perceiving morality. Western Christianity’s juridical emphasis on sin, redemption, and individual accountability may have nurtured a focus on personal moral responsibility and adherence to divine law. This contrasts with Eastern Orthodoxy’s emphasis on spiritual healing, communal salvation, and the restoration of the divine image in humanity, fostering a more holistic and restorative moral perspective.

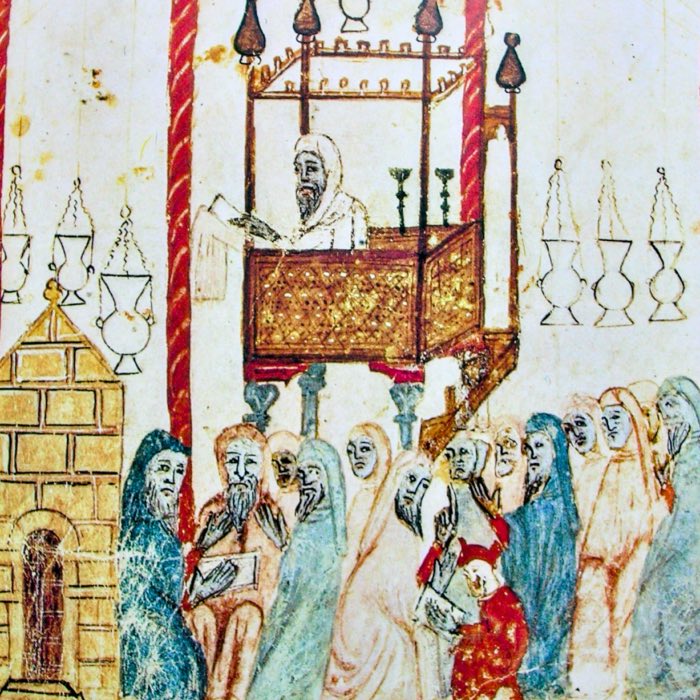

These theological differences also profoundly manifest in art and aesthetics. Western Christian art frequently reflects dramatic narratives and emotional expressions, capturing the human struggle and Christ’s historical journey. By contrast, Eastern Orthodox iconography emphasizes the mystical and participatory nature of divine realities. Icons are regarded as sacred windows into the divine, inviting worshippers into communion with the heavenly. This focus on the mystical aligns with Orthodoxy’s vision of theosis, which permeates not only spiritual life but also cultural expressions of the sacred.

References

- Lossky, Vladimir, The mystical theology of the Eastern Church, 1944, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, ISBN: 9780913836316

- Staniloae, Dumitru, The experience of God: Orthodox dogmatic theology, 1998, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, ISBN: 9780917651700

- Meyendorff, John, Byzantine theology: Historical trends and doctrinal themes, 1974, Fordham University Press, ISBN: 9780823209677

- Ware, Kallistos, The Orthodox way, 1995, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, ISBN: 9780913836583

- Athanasius of Alexandria, On the incarnation, 4th century, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, ISBN: 9780881414271

comments