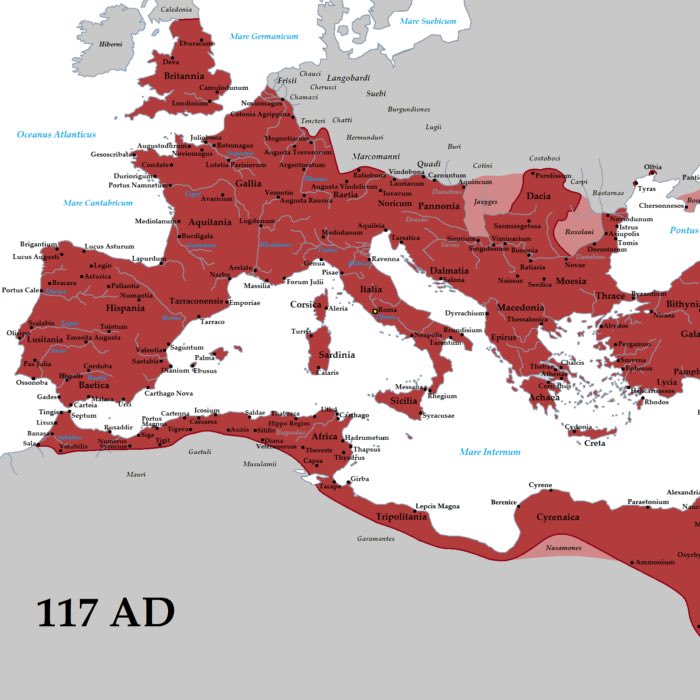

From YHWH to God: How Greek philosophy shaped Jewish and Christian perception of the Absolute

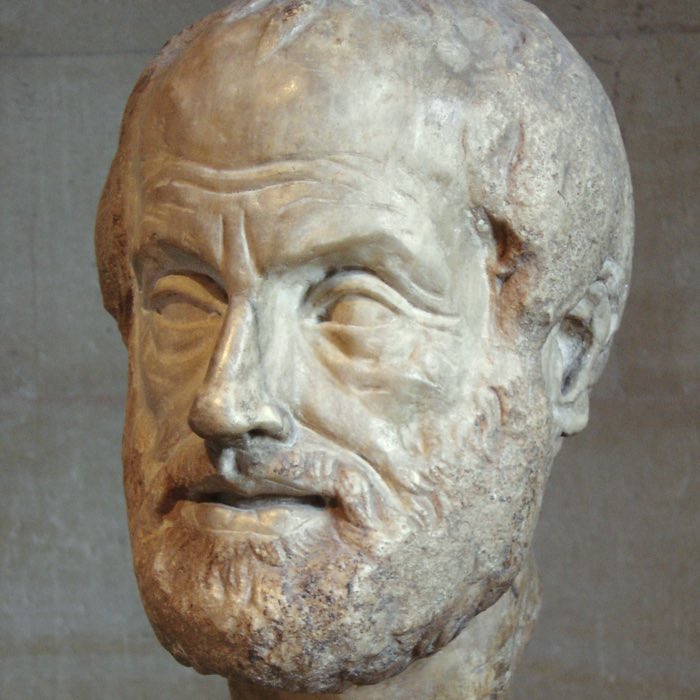

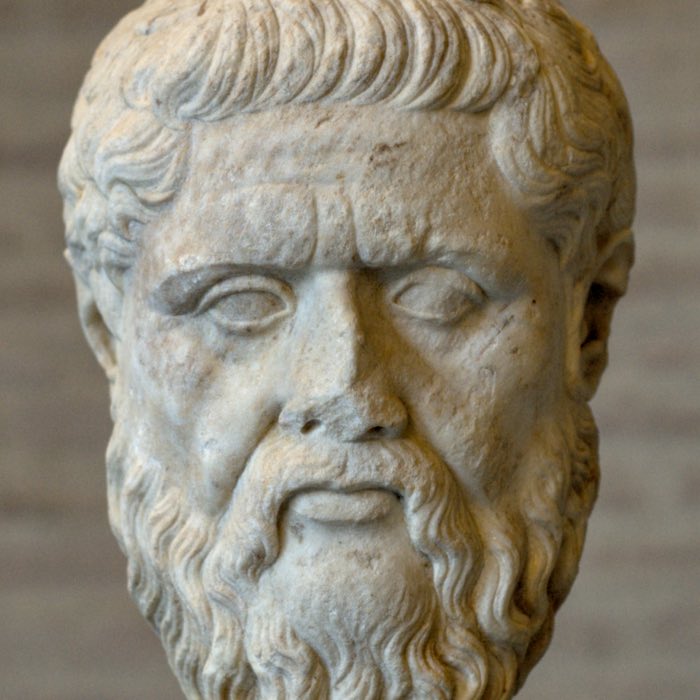

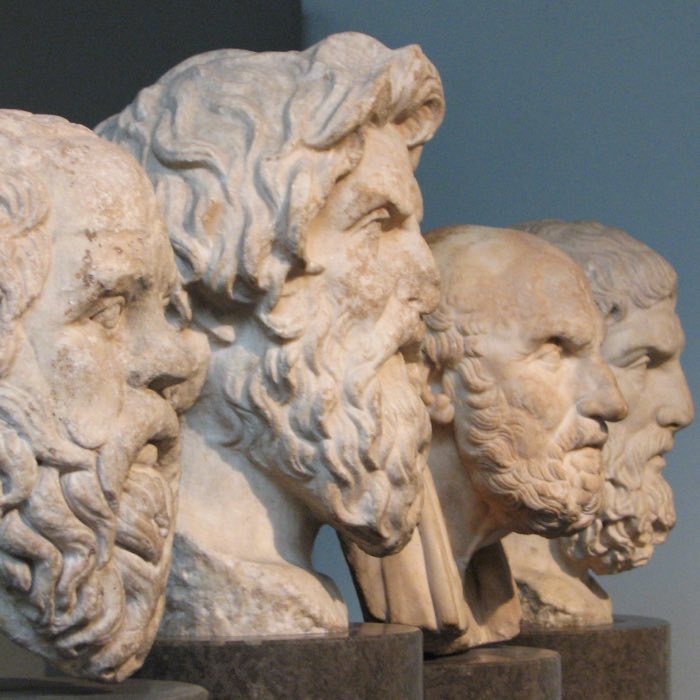

The transformation of the concept of “God” in both Judaism and Christianity is one of the most profound developments in religious history. From the anthropomorphic and personal YHWH of the Hebrew Bible to the abstract, infinite, and ineffable deity central to Christian theology and later Rabbinic Judaism, this evolution was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy. Particularly during the Hellenistic period and beyond, ideas from Platonism, Stoicism, and Neoplatonism) provided a conceptual framework that reshaped the understanding of divinity in both traditions. In this post, we explore how Greek philosophical thought transformed the perception of God in Judaism and Christianity, with emphasis on their shared roots and divergent developments.

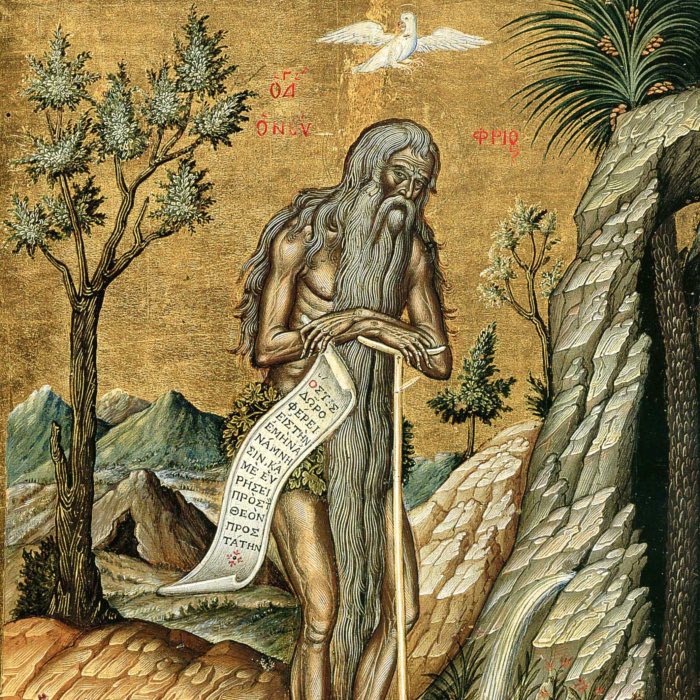

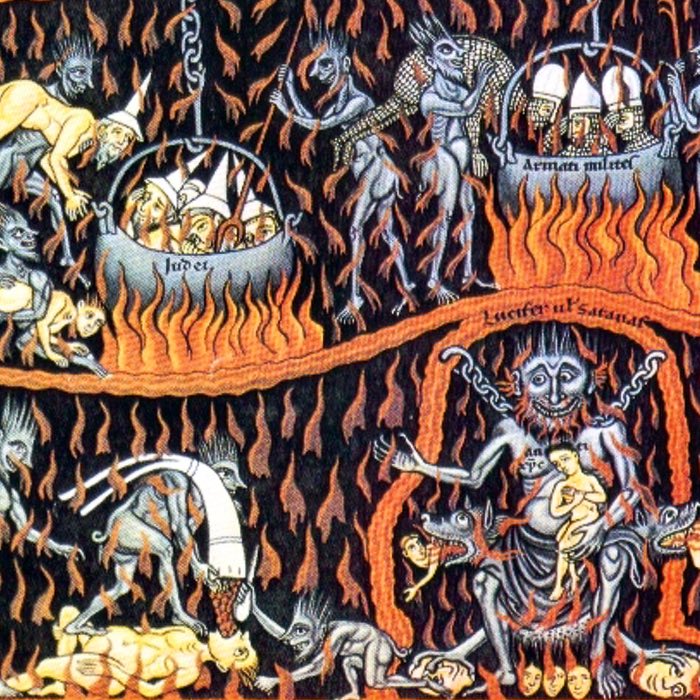

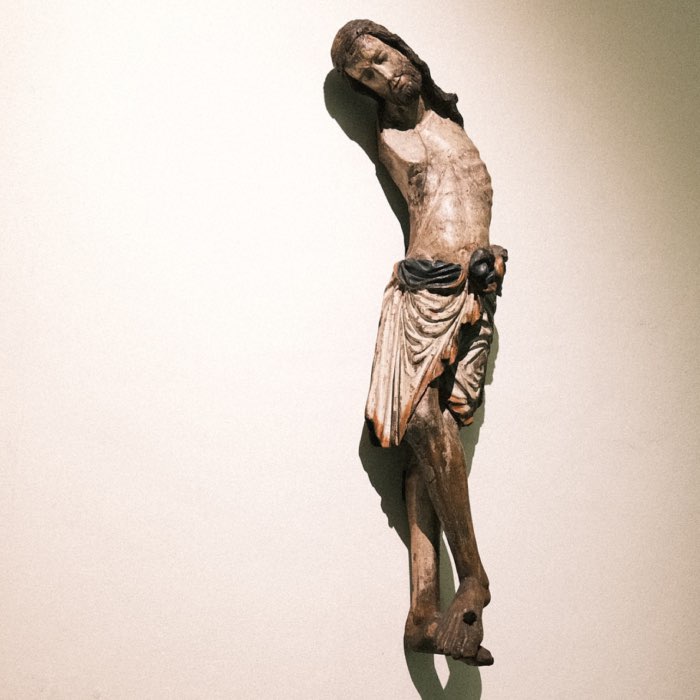

God the Father on a throne, anonymous painter from Westphalia, Germany, late 15th century. In the late Middle Ages, artists, usually commissioned by the clergy, started to depict God in human form. This is kind of ironic in a double sense: First, the Hebrew Bible prohibits the depiction of God in any form, and second, it contradicts the abstract and transcendent nature of God as understood in the Christian theology, that was fully based on the Neoplatonic) concept of the One. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

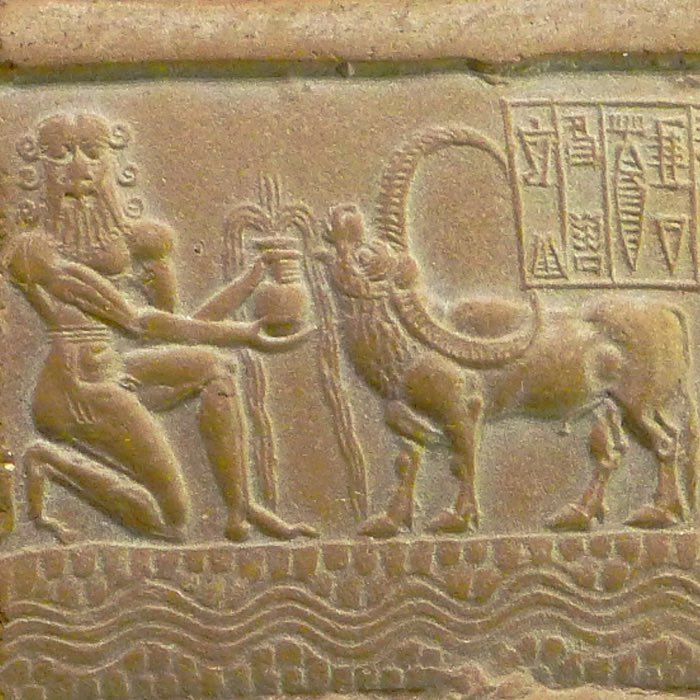

The nature of YHWH in ancient Judaism

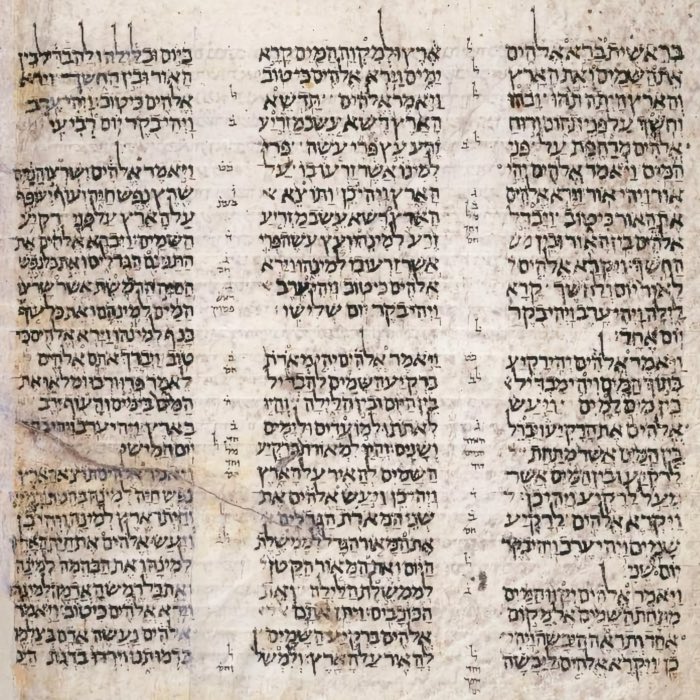

In ancient Israelite religion, YHWH was perceived as the singular, all-powerful deity of the Israelites, distinct from the polytheistic gods of surrounding cultures. Yet, this early conception of YHWH bore similarities to other ancient Near Eastern deities, by which YHWH was most likely influenced. YHWH was anthropomorphic, often depicted as having emotions, speaking directly to humans, and intervening in history. For example, the Hebrew Bible portrays YHWH as a covenant-maker (Genesis 12, Exodus 19), a warrior (Exodus 15), and a ruler who rewards and punishes based on moral conduct (Deuteronomy 28).

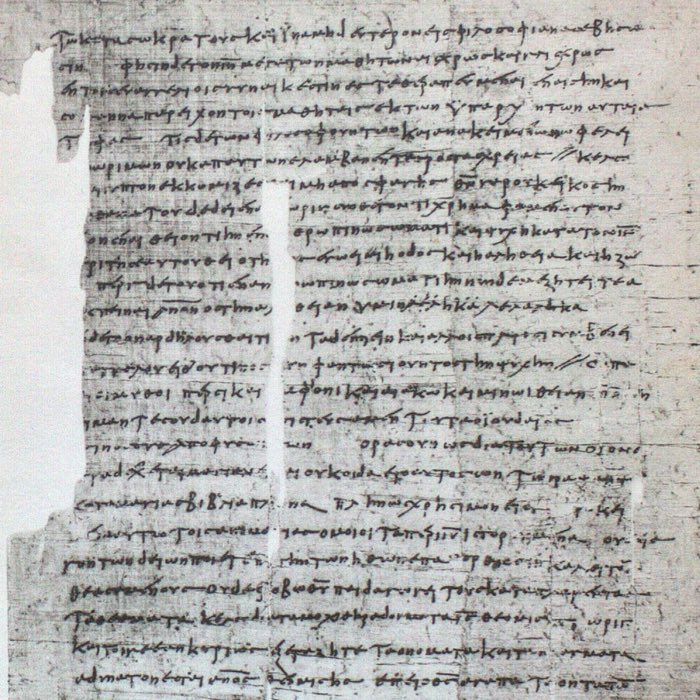

The Tetragrammaton YHWH, the name of God written in Hebrew, old church of Ragunda, Sweden. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Tetragrammaton YHWH, the name of God written in Hebrew, old church of Ragunda, Sweden. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Despite this anthropomorphism, ancient Judaism distinguished itself through its strict monotheism. While neighboring cultures worshiped pantheons, Judaism reduced divinity to a single being, declaring, “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one” (Deuteronomy 6:4). However, this singularity did not imply the philosophical abstraction later seen in Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity. YHWH remained deeply personal and historically grounded, engaged with human affairs and tied to a chosen people.

Hellenistic Judaism and the rise of philosophical abstraction

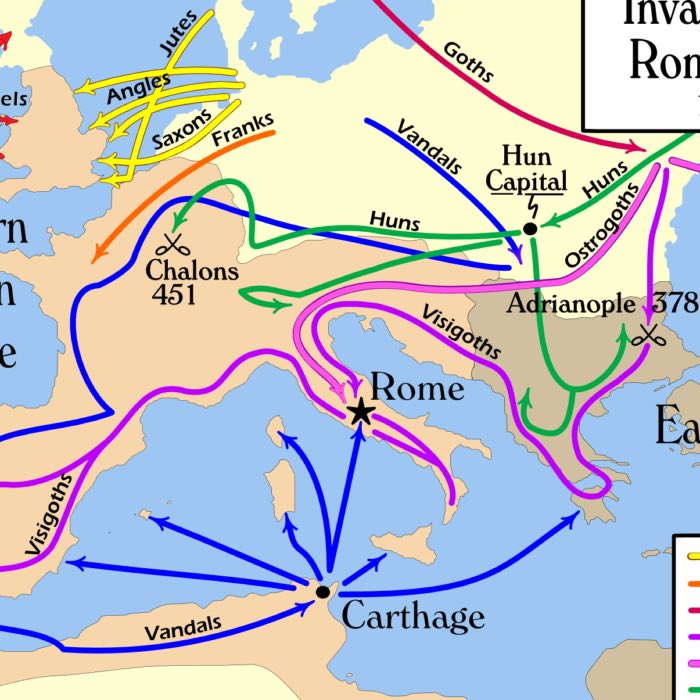

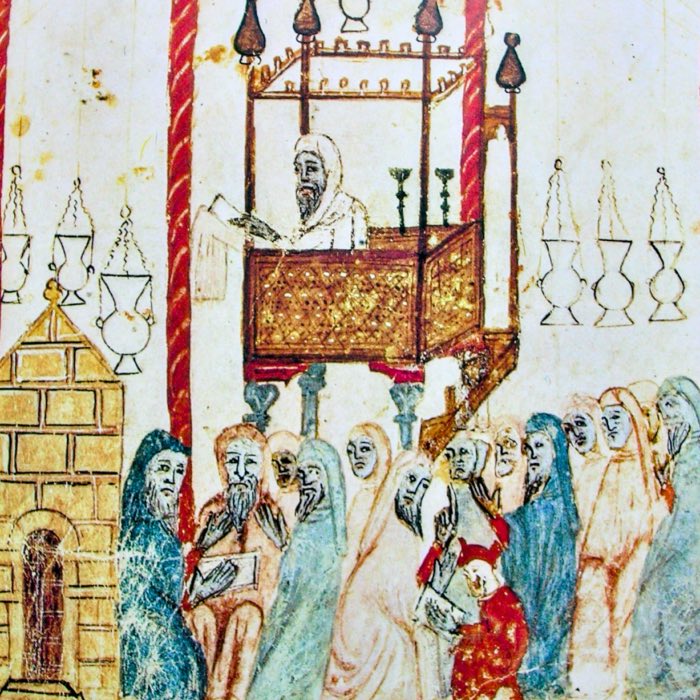

The conquest of the Eastern Mediterranean by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE brought Jewish communities into contact with Greek culture. This cultural exchange led to the emergence of Hellenistic Judaism, a synthesis of Jewish theology and Greek philosophy, particularly in places like Alexandria, Egypt.

One of the most influential figures in Hellenistic Judaism was Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE–50 CE). Philo sought to harmonize Jewish scripture with Greek philosophy, particularly Platonism and Stoicism. For Philo, the God of the Hebrew Bible was not only the God of Israel but also the ultimate, ineffable source of all reality, akin to Plato’s Good and the Stoic interpretation of the Logos. Philo reinterpreted the anthropomorphic descriptions of YHWH allegorically, emphasizing God’s transcendence and unity. For example:

- Philo identified the Logos as an intermediary between the transcendent God and the material world, a bridge between the divine and the finite.

- He argued that God could not be fully known or described, echoing Platonic ideas of the Good as beyond comprehension.

Philo’s ideas laid the groundwork for the transformation of God in both Judaism and Christianity. By reimagining YHWH as an abstract and universal deity, he helped shift the perception of God from a personal, national figure to a transcendent, philosophical Absolute.

Rabbinic Judaism and the philosophical redefinition of YHWH

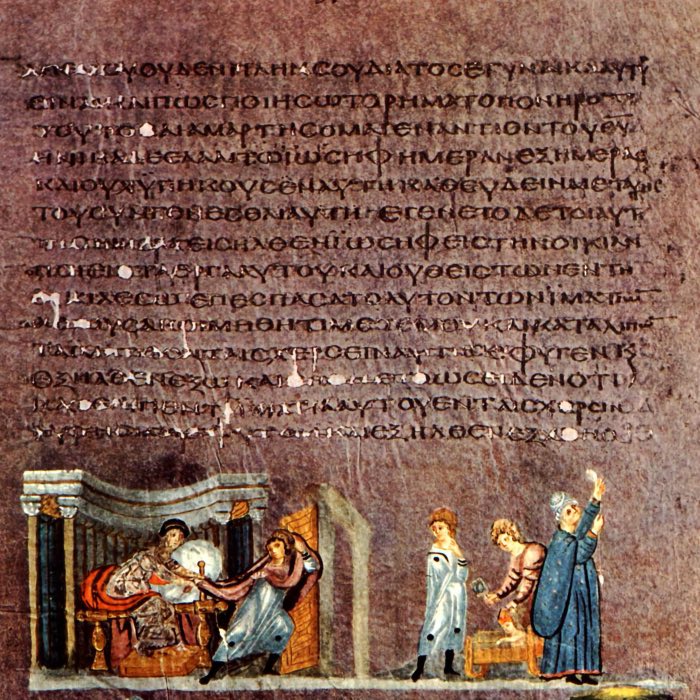

Following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Rabbinic Judaism emerged as the dominant form of Jewish religious life. During this period, Jewish thought continued to absorb and adapt elements of Greek philosophy, albeit more subtly and selectively than in Hellenistic Judaism.

Transcendence and divine unity

Rabbinic Judaism emphasized the transcendence and unity of YHWH, reflecting Greek philosophical concepts of ultimate reality. The Shema prayer (“The Lord is one”) became a central affirmation of divine unity, paralleling the Neoplatonic) One as the source of all being. The Rabbis also reinterpreted anthropomorphic descriptions of YHWH in the Hebrew Bible metaphorically or allegorically, distancing God from human attributes. This shift aligned with Greek notions of divine immutability and perfection.

Torah as divine wisdom

Rabbinic Judaism elevated the Torah from a covenantal text to an eternal cosmic principle. This idea resonates with Greek Stoic concepts of the Logos as the rational order governing the universe. The Rabbis portrayed the Torah as pre-existing creation, reflecting the philosophical idea of divine wisdom as the foundation of reality. This understanding further abstracted the concept of YHWH, embedding God’s presence in the rational and moral structure of the world.

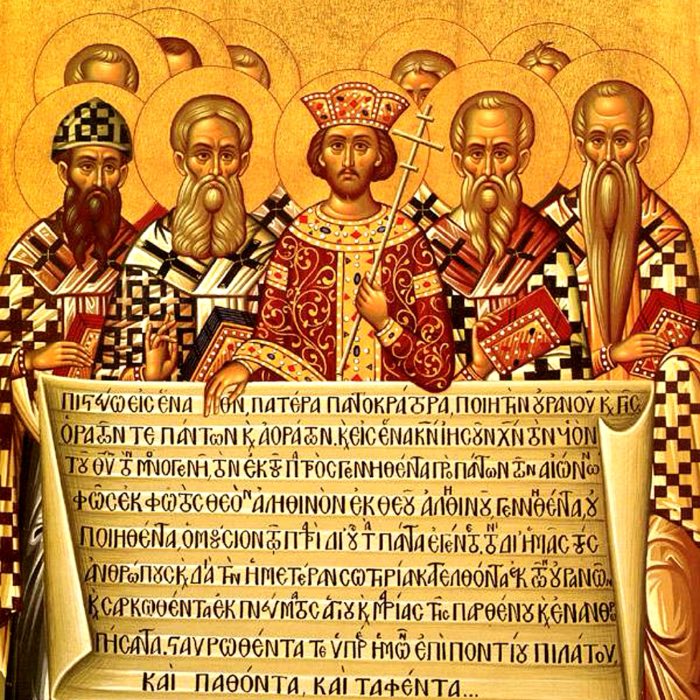

The transformation of God in early Christianity

Christianity, which emerged as a Jewish sect in the 1st century CE, inherited the Jewish conception of YHWH. Early Christians, however, were deeply influenced by Hellenistic thought, particularly as the movement spread into the Greco-Roman world. Greek philosophy played a central role in shaping Christian theology, especially in the development of the doctrine of God.

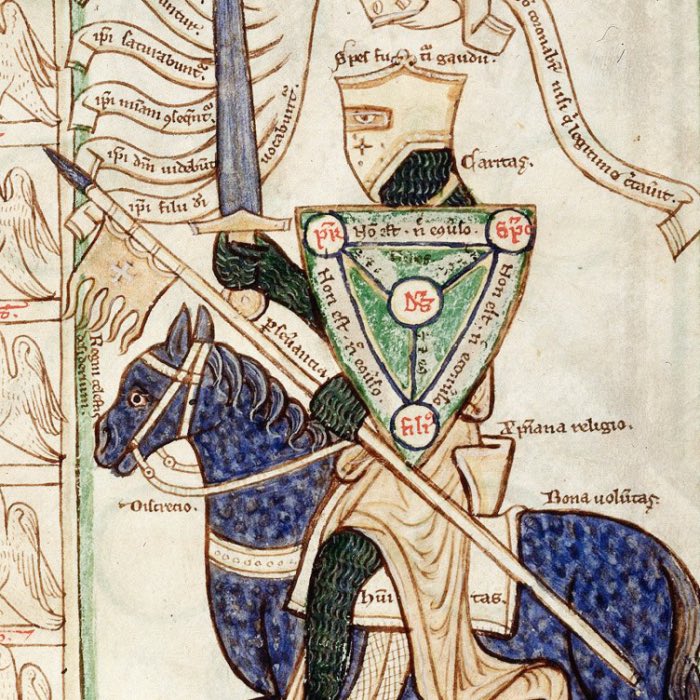

God the Father with His Right Hand Raised in Blessing, with a triangular halo representing the Trinity, Girolamo dai Libri, c. 1555. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

God the Father with His Right Hand Raised in Blessing, with a triangular halo representing the Trinity, Girolamo dai Libri, c. 1555. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

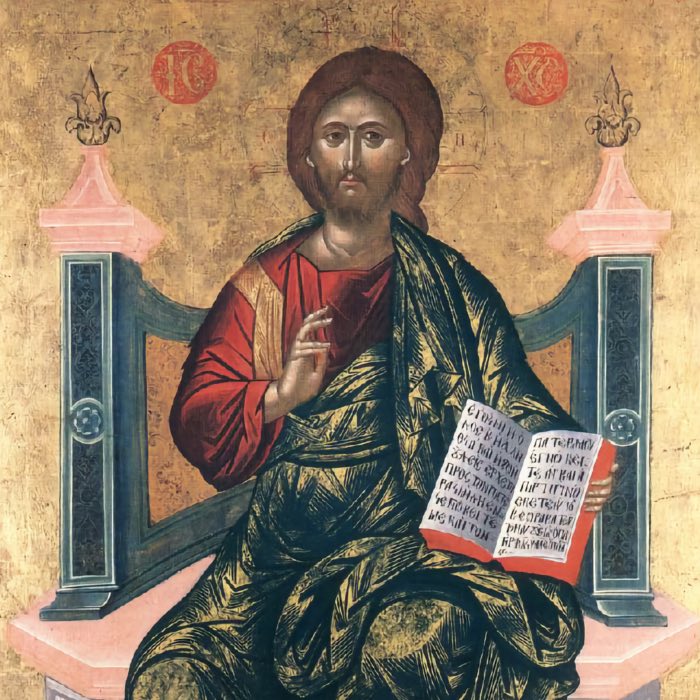

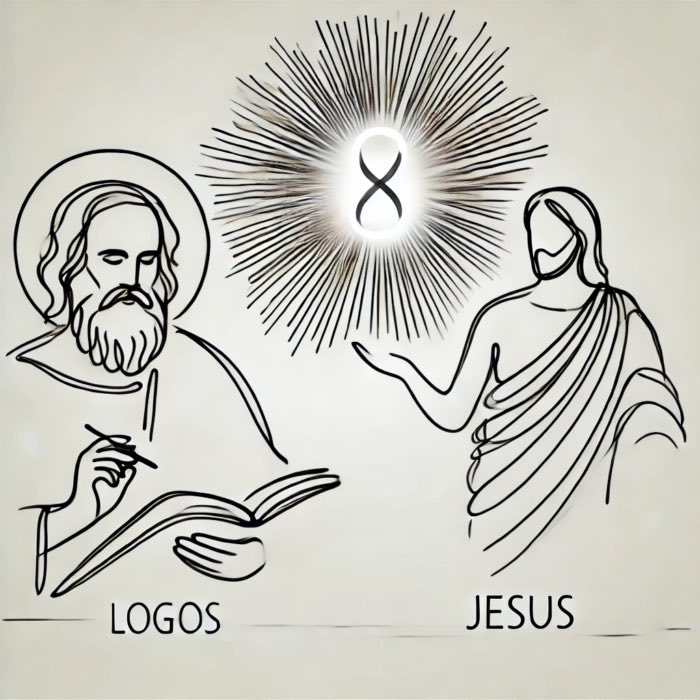

The influence of the Logos

The Gospel of John opens with the famous declaration: “In the beginning was the Word (Logos), and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1). This passage reflects a synthesis of Jewish theology with Greek philosophical ideas. The Logos, as described by John, serves as both the divine agent of creation and the incarnate Christ. This concept draws heavily on Philo’s interpretation of the Logos as an intermediary between the transcendent God and the material world.

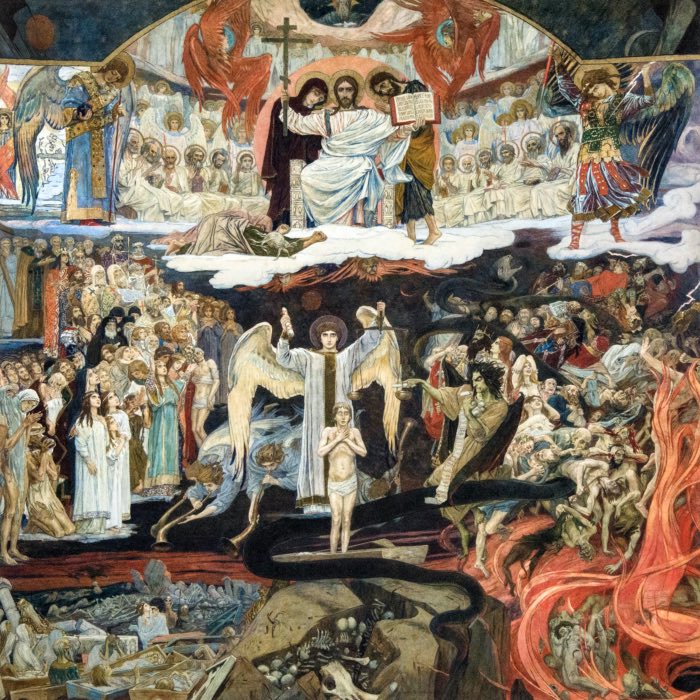

God as ultimate and infinite

Early Christian theologians, such as Origen of Alexandria and later Augustine of Hippo, incorporated Neoplatonic ideas) into their understanding of God. For example:

- Origen emphasized God’s ineffability and immutability, portraying God as the ultimate source of all being, akin to the Neoplatonic) One.

- Augustine further developed these ideas, arguing that God exists outside of time and space, embodying absolute perfection and infinity.

These philosophical influences transformed the Christian understanding of God from a personal deity to an abstract, metaphysical Absolute, aligning with the intellectual currents of the Greco-Roman world.

Divergences and parallels between Judaism and Christianity

While both Judaism and Christianity absorbed Greek philosophical ideas, their theological trajectories diverged. Rabbinic Judaism retained a strong focus on the covenantal relationship between YHWH and Israel, grounding its theology in historical and ethical terms. Christianity, by contrast, universalized its conception of God, presenting Jesus as the incarnation of the divine Logos and emphasizing the metaphysical aspects of God’s nature.

Despite these differences, both traditions were profoundly shaped by Greek thought, moving from a historically grounded and anthropomorphic understanding of God to one that emphasized transcendence, abstraction, and ultimate unity.

Conclusion

The evolution of the concept of God in Judaism and Christianity illustrates the transformative power of cultural and philosophical exchange. Greek philosophy provided the tools to reinterpret YHWH as an abstract, infinite, and transcendent being, reshaping both traditions in profound ways. In Judaism, this influence is evident in the allegorical interpretations of Rabbinic thought and the cosmic understanding of Torah. In Christianity, it is seen in the development of the Logos theology and the Neoplatonic) conception of God. These changes not only elevated the intellectual appeal of both religions but also allowed them to endure and adapt in a Hellenistic world.

References and further reading

- Mark S. Smith, The Early History Of God - Yahweh And The Other Deities In Ancient Israel, 2002, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802839725

- Mark S. Smith, The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel’s Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts, 2003, Oxford University Press; New Ed Edition, ISBN: 978-0195167689

- William G. Dever, Beyond The Texts - An Archaeological Portrait Of Ancient Israel And Judah, 2020, SBL Press, ISBN: 9780884144915

- Francesca Stavrakopoulou, God: An Anatomy, 2022, Picador, ISBN: 9781509867370

- Theodore J. Lewis, The Origin And Character Of God, 2023, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780197687543

- Ziony Zevit, The Religions Of Ancient Israel - A Synthesis Of Parallactic Approaches, 2003, A&C Black, ISBN: 9780826463395

- Laurie E. Pearce, Cornelia Wunsch, Documents Of Judean Exiles And West Semites In Babylonia In The Collection Of David Sofer, 2014, Eisenbrauns, ISBN: 9781934309575

- Tero Alstola, Judeans In Babylonia - A Study Of Deportees In The Sixth And Fifth Centuries BCE, 2020, Brill, ISBN: 9789004365414

- Daniel E. Fleming, Yahweh Before Israel - Glimpses Of History In A Divine Name, 2023, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9781108799614

- Robert Karl Gnuse, No Other Gods - Emergent Monotheism In Israel, 1997, Sheffield Academic Press, ISBN: 9781850756576

- Bob Becking, Only One God? - Monotheism In Ancient Israel And The Veneration Of The Goddess Asherah, 2001, A&C Black, ISBN: 9781841271996

- Hershel Shanks, The Rise Of Ancient Israel, 1992, Biblical Archaeology Society, ISBN: 9781880317075

- Amihay Mazar, Ephraim Stern, Archaeology Of The Land Of The Bible - 10,000-586 B.C.E, 1992, Yale University Press, ISBN: 9780300140071

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

comments