Is Christianity the most engineered religion in history?

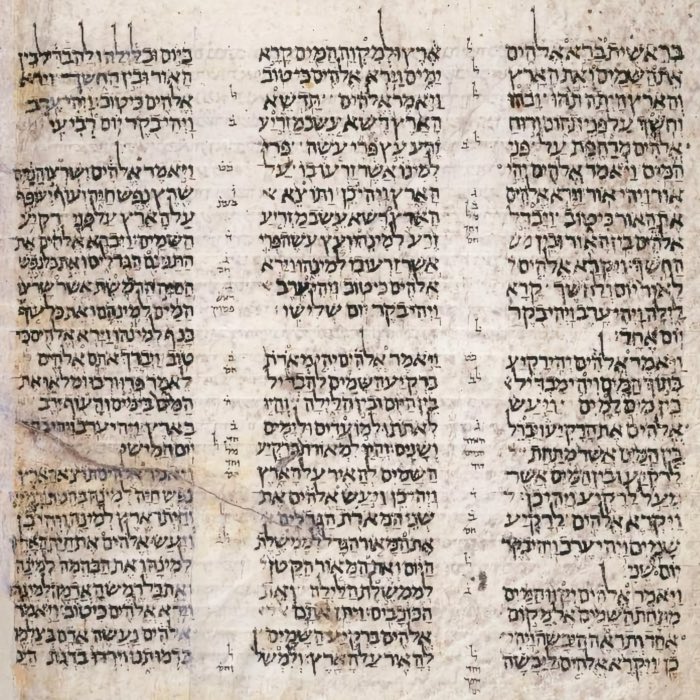

The question in the title of this post is of course ironic. Every religion is a construct that evolves over time, adapting to the cultural, social, and political circumstances of its adherents. Religions are shaped by their historical contexts, assimilating ideas and practices to remain relevant. However, Christianity stands out for its systematic appropriation of Greco-Roman philosophical concepts and Jewish traditions to form a comprehensive theological framework. In this post, we (provocatively) explore how Christianity, often perceived as a divine revelation, is deeply rooted in Greco-Roman philosophy and Jewish apocalyptic ideas. We further examine which elements of Christian theology are uniquely Jewish or Christian, contrasting them with their Greco-Roman counterparts.

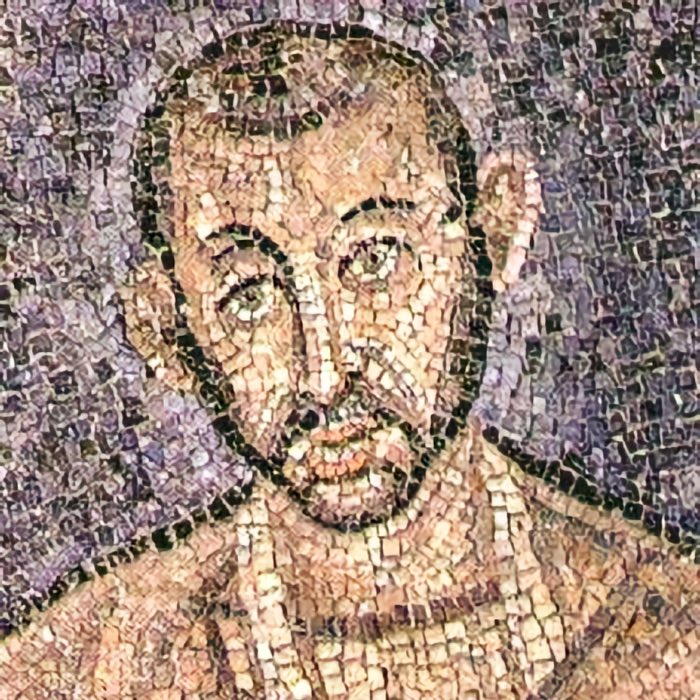

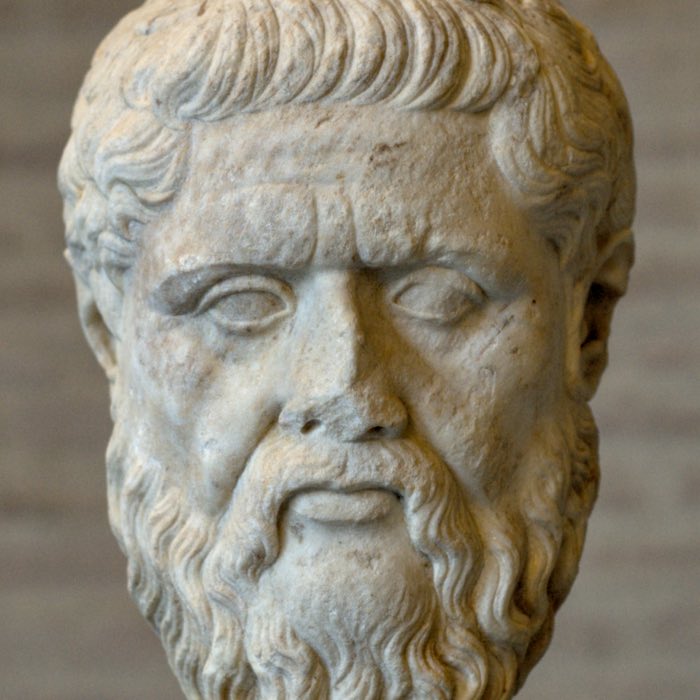

Christ Pantocrator, Elias Moskos, icon, egg tempera on wood, 1653. The motif Jesus Christ as Pantocrator (ruler of all) is a common theme in Eastern Orthodox iconography. The image depicts Christ in a frontal pose, holding a book of Gospels in his left hand and making a gesture of blessing with his right hand. The Gospels book in his hand stands for the divine wisdom and the identification of Jesus as the Logos, a concept deeply rooted in Greco-Roman philosophy. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The origins of Christianity: From mystery cult to theological system

Christianity originated as a Jewish apocalyptic mystery cult centered around a savior figure called “Jesus”. Initially, this figure was likely mythical, embodying Jewish messianic expectations and soteriological hopes. Early writings, such as Paul’s epistles, depict Christ as a cosmic entity whose death and resurrection promise salvation. Over time, this mythological figure was historized in the Gospels, creating a narrative framework that grounded the cult in a tangible past.

The transition from a localized Jewish sect to a universal religion required theological expansion. As Christianity spread throughout the Greco-Roman world, it absorbed philosophical concepts to construct a cohesive and appealing system. This post-hoc synthesis adapted the mystery cult’s foundational ideas to align with Greco-Roman intellectual traditions while retaining distinctive Jewish motifs.

Original Jewish or Christian concepts

While much of Christian theology is rooted in Greco-Roman philosophy, some concepts are uniquely Jewish or distinctly developed within Christianity. These include:

Monotheism

The idea of one supreme God is foundational to Judaism and Christianity. While Greek philosophy entertained notions of a prime mover or ultimate source (e.g., Aristotle’s unmoved mover, Plotinus’ One), polytheism remained dominant in Greco-Roman religion. While Christianity’s monotheism is inherited from Judaism, some might argue that early Christian Trinitarian theology — with its distinction between God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit — could appear less strictly monotheistic compared to Jewish norms. Nevertheless, Christianity maintained the fundamental concept of one supreme God, which was a significant departure from the polytheism dominant in Greco-Roman religion.

Fear of God and godliness

The Jewish and Christian demand for absolute piety and reverence toward God is unparalleled in Greco-Roman traditions. While piety (eusebeia) was respected in Greek and Roman culture, it was not accompanied by the intense, fear-based devotion characteristic of Jewish and Christian thought. This reflects a uniquely Judaic view of humanity’s relationship with the divine, emphasizing obedience and submission.

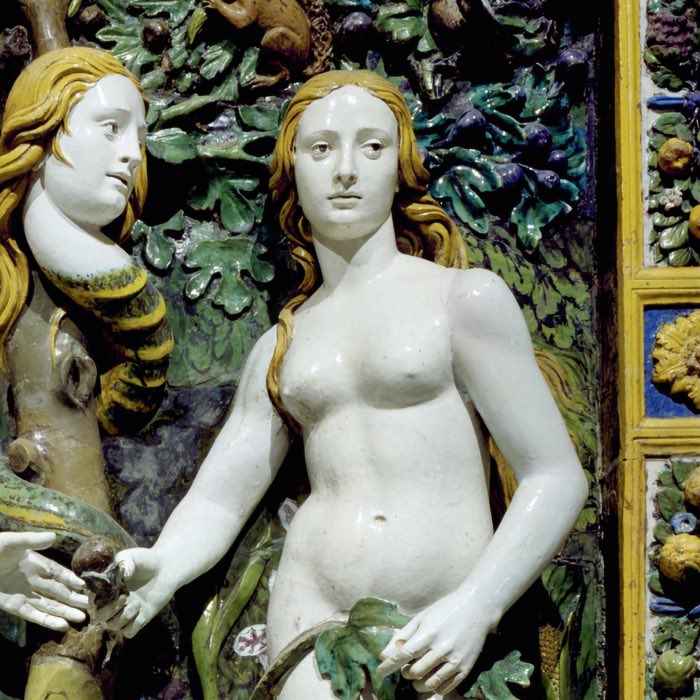

Sin as a universal moral failing

The concept of sin as a universal moral failing is a distinctly Jewish and Christian idea. While Greco-Roman traditions recognized moral failings and civic offenses, they framed these in terms of honor, shame, or legal transgressions rather than as intrinsic flaws requiring divine forgiveness. In Judaism, sin is seen as an offense against God that necessitates atonement, often through rituals or sacrifices. Christianity expanded this notion with the doctrine of original sin — an inherited state of moral corruption stemming from Adam and Eve’s fall in the Garden of Eden. This idea, articulated by Paul and later developed by Augustine, posits that all humanity is born in a state of sin, requiring divine intervention for redemption. Such a view is absent in Greco-Roman philosophy, where moral failings were typically tied to ignorance or lack of self-control rather than an innate fallen nature.

Homophobia

Christian opposition to homosexuality finds its roots in Jewish scriptures, such as Leviticus 18:22. However, the interpretation and enforcement of this prohibition evolved within the Christian tradition, shaped by broader cultural shifts in the Greco-Roman world. While Jewish scripture laid the foundation, early Christian leaders amplified this condemnation, partly as a response to the relatively permissive attitudes toward same-sex relationships in Greco-Roman society. This shift marked a departure from Greco-Roman norms, where certain forms of homosexual relationships were not only accepted but idealized in specific contexts, such as those discussed in Plato’s Symposium.

Suppression of women

While Greek philosophy occasionally entertained more egalitarian views – for instance, Plato’s Republic envisioned a society where women could hold the same roles as men –, patriarchal attitudes were prevalent in both Jewish and Greco-Roman societies. However, early Christianity sometimes offered women opportunities for leadership that were more progressive than those in surrounding cultures. Women such as Phoebe and Priscilla held positions as deaconesses or teachers, and female martyrs were celebrated for their faith.

Yet, as Christianity transitioned from a persecuted sect to an imperial religion, these roles diminished. The institutional Church increasingly aligned with patriarchal norms, marginalizing women from leadership. Canon law and doctrinal teachings further entrenched male dominance, with women’s roles largely confined to subservient or symbolic positions. Over time, Christianity moved from moments of potential gender equity to reinforcing the societal status quo, often framing this regression as divinely ordained.

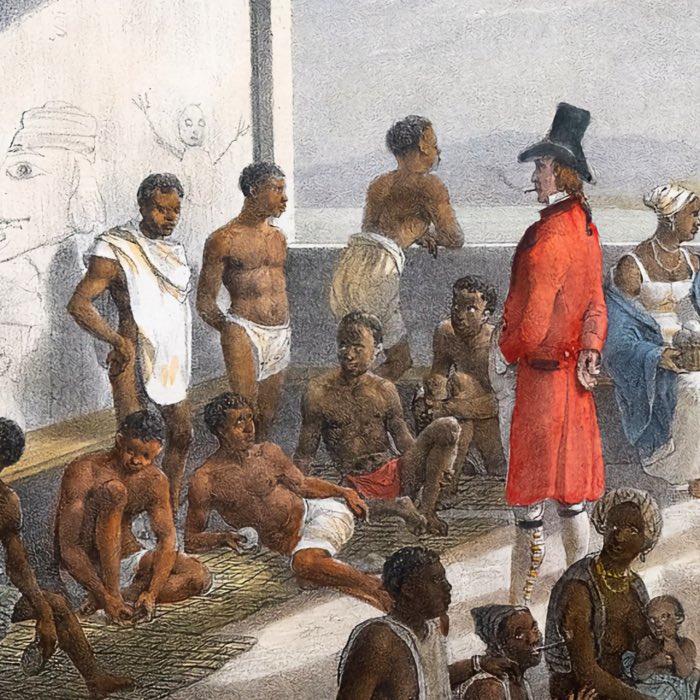

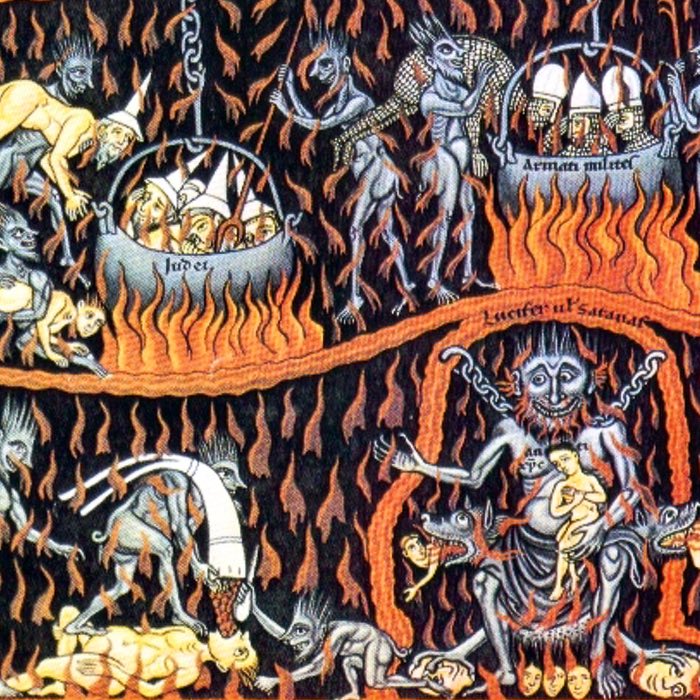

Antisemitism

Antisemitism is a uniquely Christian phenomenon, emerging as the early Church sought to distance itself from its Jewish roots. Greek and Roman philosophy did not degrade specific religious or ethnic groups; rather, it often admired the customs of other cultures. Christianity’s theological anti-Judaism, which framed Jews as “Christ’s murderers” and their degradation to “witnesses” as proposed by Augustine of Hippo, laid the groundwork for centuries of persecution, violence, and murder.

Suppression of different opinions

Greek and Roman philosophical traditions encouraged critical discourse and the coexistence of diverse schools of thought. Christianity, however, quickly moved to suppress heresies and enforce orthodoxy. The persecution of dissenters and the end of philosophical pluralism marked a sharp break from Greco-Roman intellectual traditions. This intolerance of differing opinions was a distinctly Christian development, driven by the need to maintain doctrinal unity.

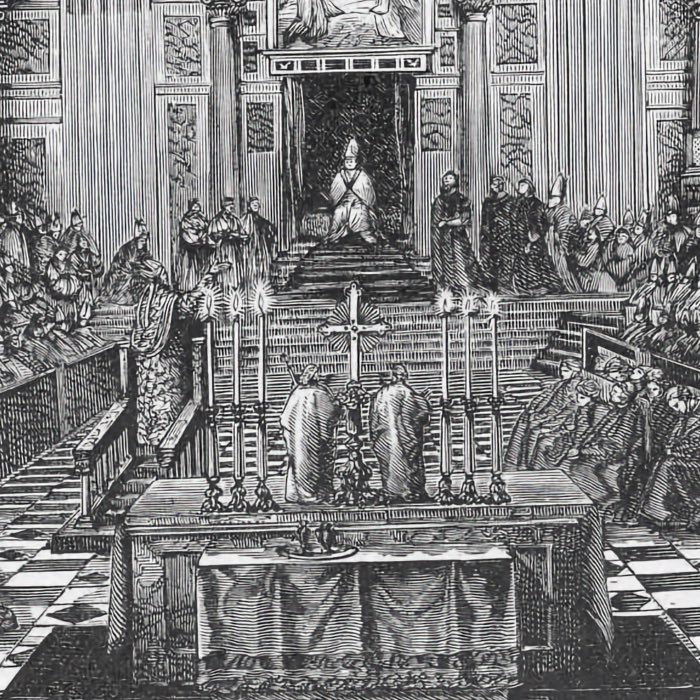

The Church as a centralized institution

One of Christianity’s most significant and original contributions is the Church as a centralized and authoritative institution. While the Roman Empire provided administrative structures that Christianity later adapted, no equivalent guiding or controlling instance existed among Greek philosophical schools. In contrast to the decentralized and often competing schools of thought in Greek philosophy, Christianity developed a hierarchical, institutionalized structure that administrated, directed, defined, and controlled theological content.

This organizational model allowed Christianity to consolidate doctrine, suppress internal dissent, and maintain a unified theological framework. The establishment of ecclesiastical hierarchy — bishops, councils, and ultimately the papacy — provided a mechanism to enforce doctrinal consistency across vast regions. Unlike philosophical traditions where individual thinkers could challenge and refine ideas, Christian theology became increasingly regulated by Church authority. This institutionalization played a key role in Christianity’s longevity, but it also facilitated the suppression of alternative interpretations and rival religious movements.

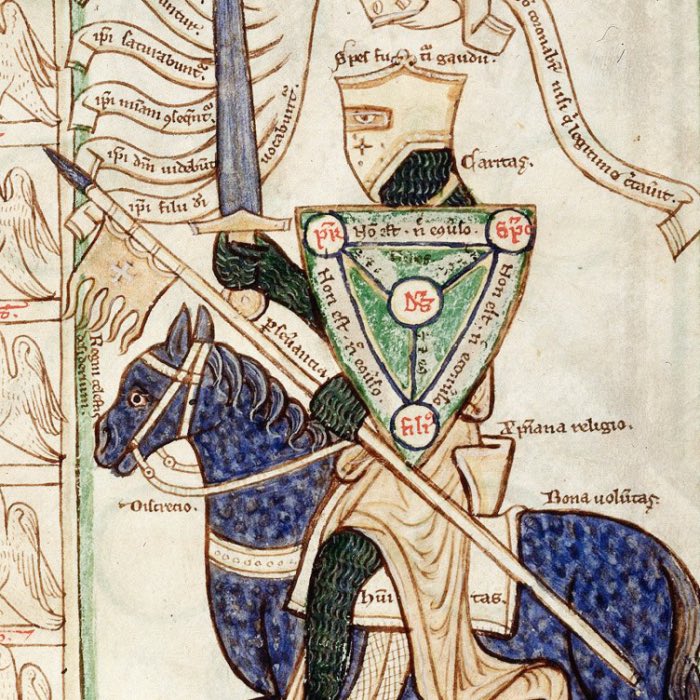

Holy War

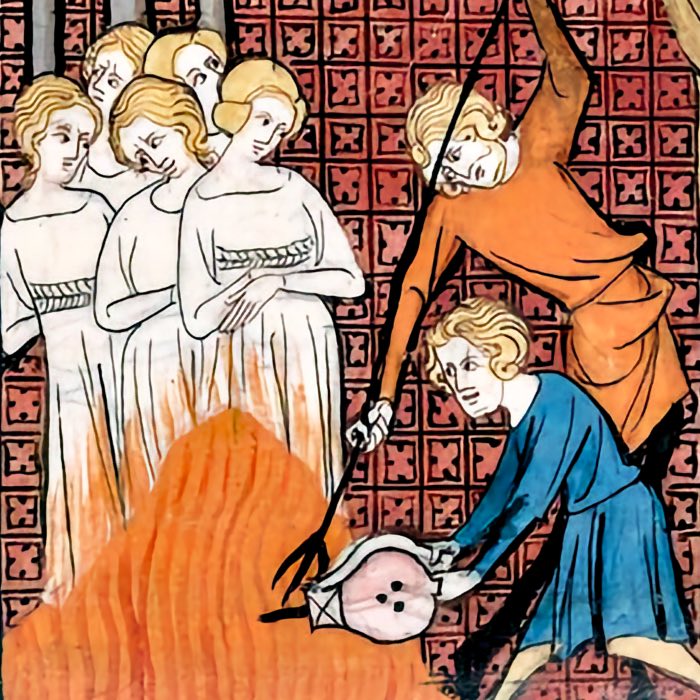

The concept of holy war is another uniquely Christian development, particularly in its institutionalized and theologically justified form. While warfare in the ancient world was often waged for territorial, political, or economic reasons, Christianity introduced the idea that war could be divinely sanctioned as a means of defending or spreading the faith. This concept took shape in the Middle Ages, particularly with the Crusades, where Christian leaders declared military campaigns as spiritually meritorious acts, offering indulgences and divine favor to those who participated.

Although the Hebrew Bible contains narratives of divinely sanctioned battles, Judaism never developed a systematic doctrine of holy war comparable to what emerged in Christendom. Likewise, Greek and Roman philosophy lacked any theological justification for war beyond state interests or personal honor. The idea of a war fought explicitly for the defense or expansion of a religious system — one that promised eternal rewards for combatants — was a distinctly Christian innovation, marking a fundamental departure from classical concepts of warfare and morality.

Theological framework derived from Greco-Roman concepts

Several key concepts in Christian theology can remarkably be traced back to pre-existing Greco-Roman philosophical ideas. Christianity synthesized these ideas into a cohesive theological framework – which Christianity initially lacked. This synthesis allowed Christianity to appeal to diverse cultural and intellectual traditions while embedding itself within the Greco-Roman world. It enabled its transformation from a Jewish apocalyptic sect into a universal religion. In the following, we will illustrate how key philosophical concepts were transformed and integrated into Christian theology, examining their original meanings and subsequent adaptations.

The one

In Neoplatonism, “the One” refers to the ultimate, ineffable source of all reality, transcending being and thought. It was seen as the origin of all existence, yet entirely beyond comprehension or direct interaction with the material world. Early Christian theologians, such as Augustine, adapted this concept to describe God as the singular, infinite creator who is the source of all existence. However, Christianity introduced a significant departure from Neoplatonic abstraction by emphasizing that God is personal and relational, engaging actively with creation through acts of love, providence, and redemption. This transformation made the idea of the One not only a metaphysical principle but also the central figure of a narrative of salvation.

Logos

The Logos, a central concept in Stoicism and Neoplatonism, was understood as the rational principle organizing the cosmos and governing its order. In Stoicism, the Logos was immanent, pervading all creation as a universal reason, while in Neoplatonism, it functioned as a bridge between the ineffable One and the material world. Christianity, particularly in the Gospel of John, dramatically transformed this concept by identifying Jesus as the incarnate Logos. Rather than being an abstract, impersonal principle, the Logos in Christian theology became a personal and relational figure, embodying divine reason and acting as the mediator between God and humanity. This adaptation not only emphasized the personal and salvific dimensions of the Logos but also framed it within a historical and redemptive narrative, bridging the divine and human in a way that diverged from its Greco-Roman philosophical origins.

The nous

The nous, or divine intellect, in Greek philosophy (particularly in Aristotle and Plotinus), was considered the intermediary between the One and the material world, functioning as the faculty through which divine truths were understood and the cosmos was ordered. In Christian theology, the concept of the nous was transformed to align with the belief that humans, made in the image of God, possess a unique capacity to perceive divine truth. While Greek philosophy saw the nous as an abstract intellectual principle, Christianity emphasized its role in personal spiritual awareness, framing it as the seat of understanding for divine revelation and moral discernment. This redefinition underscored the relational and participatory nature of human engagement with God.

Theosis

In Neoplatonism, theosis referred to the soul’s ascent toward unity with the divine through intellectual contemplation and self-purification. It involved transcending the material world and aligning oneself with the divine essence. Christianity adapted this concept significantly, emphasizing theosis as a process of becoming more like God through divine grace, sanctification, and active participation in God’s life. This adaptation, particularly prominent in Eastern Orthodox theology, reframed theosis not merely as a metaphysical ascent but as a relational transformation enabled by Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection. It highlighted the personal and communal dimensions of deification, making it accessible to all believers through prayer, sacraments, and virtuous living, rather than exclusive to philosophical elites.

The demiurge

In Platonic thought, the demiurge is the artisan-like figure who shapes the material world from preexisting chaos. Christianity rejected the dualism implicit in this idea, affirming God as both the creator of matter and spirit, thus integrating the demiurge’s role into the singular Christian God.

Absence of good

The concept of evil as the absence of good (privatio boni) originated in Neoplatonism and was developed by Augustine. Christianity adopted this idea to explain the problem of evil, arguing that evil is not a substance but a corruption or privation of God’s good creation.

Oikeiosis

Oikeiosis, a Stoic concept describing the natural inclination to care for oneself and others, parallels Jesus’ teachings on universal love and neighborly care. Christianity expanded this concept by emphasizing agape, or selfless love, as central to moral and spiritual life.

Stoic virtue

The Stoic ideal of virtue as living in accordance with nature and reason influenced Christian ethics. The cardinal virtues of prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude were integrated into Christian moral theology, complementing theological virtues like faith, hope, and love.

Dogma

The Greco-Roman emphasis on established doctrine (dogma) for maintaining philosophical schools influenced Christianity’s development orthodoxy to ensure theological unity and control over interpretation. We will further discuss this topic in a subsequent section.

The tripartite soul

Plato’s concept of the soul having three parts — rational, spirited, and appetitive — formed a cornerstone of his philosophical anthropology, illustrating the harmony and tension within human nature. This tripartite model influenced early Christian thought, particularly through Augustine, who adapted it to describe the inner struggle between spirit and flesh. Augustine aligned the rational part of the soul with the human capacity to know and love God, the spirited part with moral courage and resistance to sin, and the appetitive part with desires and temptations. This reinterpretation integrated the tripartite soul into Christian teachings on sin, redemption, and the necessity of divine grace to restore order and harmony within the human person.

Emanation

Plotinus’ theory of reality emanating from the One profoundly shaped Christian Neoplatonism. In his framework, all of existence flows in a hierarchical manner from the ineffable One, through the nous (divine intellect), and into the material world, with each level being a lesser reflection of the divine. Early Christian theologians, such as Pseudo-Dionysius, adapted this model to describe the relationship between God, creation, and humanity. While retaining the hierarchical structure, Christianity reinterpreted it through a personal and relational lens, presenting God not as an abstract source but as a loving Creator who actively sustains and engages with His creation. Furthermore, the Christian emphasis on redemption and grace altered the purely metaphysical ascent in Neoplatonism, integrating it into a narrative of divine intervention and salvation.

Providence (pronoia)

The Stoic idea of a rational, purposeful order to the universe (pronoia) was integrated into Christian theology as divine providence. In Stoicism, this order was seen as an inherent, unchanging principle governing all existence with logic and necessity. Christianity adapted this concept by portraying God’s providence as both rational and benevolent, emphasizing not only a logical order but also a personal and caring divine will actively involved in the world. This shift imbued the Stoic framework with relational and moral dimensions, presenting God as a creator who nurtures, guides, and intervenes in creation to achieve a purposeful and loving design.

Apokatastasis

Originating in Stoicism and Neoplatonism, the idea of ultimate restoration was integrated into Christian theology by Origen, who envisioned a final reconciliation of all creation with God. In Stoic philosophy, this concept was tied to the cyclical renewal of the cosmos, while Neoplatonism emphasized the eventual return of all existence to the ineffable One. Origen adapted these ideas into his Christian vision of apokatastasis, proposing that even the damned, including fallen angels, could eventually be restored to divine communion. This controversial view emphasized God’s boundless mercy and the transformative power of divine love, though it was later rejected by the institutional Church for its perceived conflict with eternal damnation.

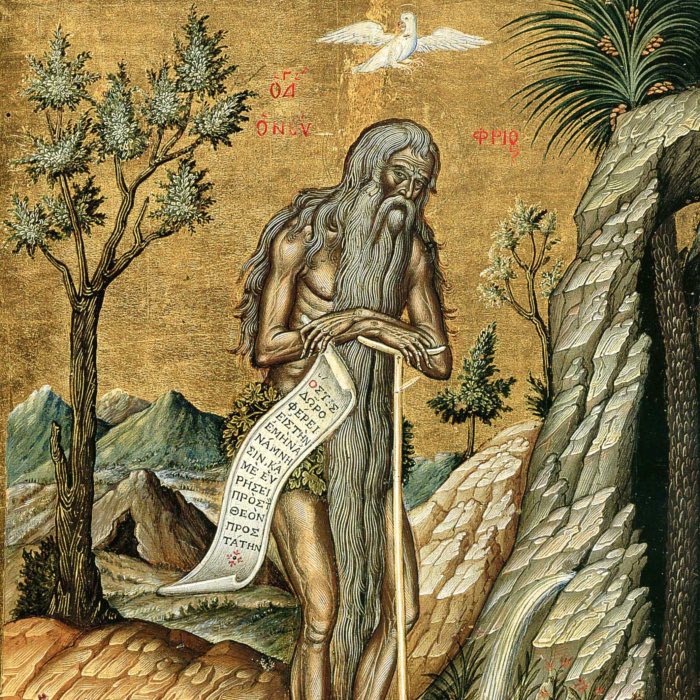

Ethical asceticism

The Stoic and Neoplatonic emphasis on self-discipline and mastery over passions deeply influenced Christian ascetic practices, particularly in monastic traditions (see, e.g., desert father). In Stoicism, asceticism was tied to living in harmony with nature and exercising reason to overcome destructive emotions, while Neoplatonism saw it as a means of purifying the soul and ascending toward unity with the divine. Christianity adapted these ideas by framing asceticism as a path to spiritual perfection, centered on the imitation of Christ’s self-sacrifice and submission to God. This Christian interpretation imbued ascetic practices with a relational and redemptive dimension, emphasizing prayer, fasting, and self-denial not just for personal enlightenment but as acts of devotion and service to God.

Teleology

Aristotle’s view that everything has a purpose (telos) informed Christian doctrines about divine design and humanity’s ultimate purpose, emphasizing God’s intentionality in creation and salvation.

Logos spermatikos

The Stoic idea of a “seminal Logos” (Logos spermatikos) pervading the cosmos influenced early Christian theology, particularly in Justin Martyr’s writings, where he described Christ as the Logos manifest in creation and history. In Stoicism, the seminal Logos was seen as the rational principle that infused all of nature, acting as the organizing force behind the universe. Justin Martyr (ca. 100 - 165) extended this idea by portraying Christ not just as a principle but as the personal and divine agent through whom all things were made. This adaptation transformed the impersonal Stoic Logos into a central figure of salvation history, emphasizing the role of Christ in both the creation and redemption of the world. By doing so, Justin connected classical philosophical thought with the Christian message, making it accessible to a Greco-Roman audience.

Immortality of the soul

Platonic dualism, which emphasized the separation between the immortal soul and the perishable body, greatly influenced early Christian thought. Christians adopted the concept of the soul’s immortality, aligning it with the promise of eternal life. However, they rejected the Platonic idea of the preexistence of souls, focusing instead on the soul’s creation by God at conception or birth. Origen’s controversial view, which included belief in the preexistence of souls, was later condemned by the Church, as it conflicted with the doctrine of the soul’s unique and temporal creation. This adaptation reflects Christianity’s integration of Platonic ideas while redefining them within a theological framework centered on divine creation and eschatology.

Hylomorphism

Aristotle’s theory of matter and form, which posits that all physical entities are composed of both material substance and an organizing principle (form), deeply influenced Christian theological debates. This framework was particularly significant in discussions about the resurrection, as it provided a philosophical basis for affirming the unity and interdependence of body and soul. Christian theologians, while rejecting certain pagan connotations, used hylomorphism to argue that the resurrection would restore the full integrity of human nature, emphasizing the goodness and divine purpose of material creation. This integration highlighted the sanctity of the physical world, countering dualistic tendencies that viewed the body as inherently corrupt.

Virtue ethics

The Greek emphasis on cultivating virtues influenced Christian moral teachings. Aristotle’s cardinal virtues were integrated with theological virtues, creating a comprehensive moral framework.

Pater familias

Roman family law and the ideal of the father as head of the household influenced Christian teachings on familial roles, Church leadership, and the image of God as “Father.”

Natural law

The Stoic and Ciceronian concept of natural law as a universal moral order, rooted in reason and the inherent structure of the cosmos (the logos), profoundly influenced Christian theology. Stoicism emphasized that natural law was accessible to all rational beings and governed moral behavior as a reflection of divine reason. Christianity adopted and transformed this idea, presenting natural law as not only a rational framework but also as divinely ordained, emphasizing that reason and conscience were direct gifts from God. This Christian interpretation reinforced the universality of moral truths while linking them explicitly to God’s will and governance, embedding the concept within a theological narrative of creation and salvation.

Civic virtue

Roman ideals of duty and responsibility informed Christian teachings on charity, social justice, and the common good, extending these virtues into spiritual and communal life.

Theoria

The Greek concept of contemplative life (theoria) as the highest form of existence was a cornerstone of Platonic and Aristotelian thought, wherein the ultimate purpose of human life was to contemplate truth, beauty, and the divine. In Greek philosophy, theoria represented an intellectual pursuit of understanding the eternal realities beyond the material world. Christianity adapted this concept, integrating it into mystical traditions and monastic ideals. In Christian theology, theoria came to signify not only intellectual contemplation but also a deeply spiritual practice of prayer, reflection, and communion with God. It emphasized the transformative experience of divine union, where the believer’s focus shifted from theoretical knowledge to a relational encounter with the divine, thereby combining the Greek ideal of contemplation with the Christian emphasis on personal and communal spirituality.

Katabasis and anabasis

These Greek metaphors of descent (katabasis) and ascent (anabasis) were originally used in philosophical and religious contexts to describe the soul’s journey from the material world to the divine and back. In Neoplatonism, for example, the soul “descended” into the material realm from the divine source and sought to “ascend” back through contemplation and purification. Christianity adapted these metaphors to describe Christ’s incarnation as the ultimate descent, where God took on human form, and humanity’s ascent to divine union through salvation, particularly in theosis. This Christian reinterpretation emphasized not only a metaphysical journey but also a relational one, where the descent of Christ enabled the ascent of humanity, bridging the gap between the finite and the infinite in a personal and redemptive way.

Mystery religions

The initiation rites and themes of salvation in Greco-Roman mystery religions, such as the Eleusinian and Mithraic Mysteries, profoundly influenced Christian sacramental theology. These mystery cults emphasized secret rituals of initiation, symbolic death and rebirth, and communal meals that united participants with the divine. Christianity adopted and reinterpreted these elements, particularly in the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist. Baptism came to symbolize the believer’s death to sin and rebirth into a new life in Christ, mirroring the transformative initiation of mystery rites. Similarly, the Eucharist echoed the communal meals of these cults, but with a distinct focus on Christ’s sacrifice and ongoing presence among believers. This adaptation imbued the Christian sacraments with both theological depth and cultural resonance, enabling early Christianity to appeal to a population already familiar with the spiritual power of such rituals.

Theoria-Praxis dichotomy

The Greek distinction between theoria (contemplation) and praxis (practical action) informed Christian monasticism and profoundly shaped its spiritual practices. In Greek philosophy, particularly in Plato and Aristotle, theoria was considered the highest form of human activity, involving the intellectual pursuit of truth and the contemplation of the divine. Praxis, on the other hand, referred to ethical actions and practical engagement in the world. Christian monastic communities adapted this framework by elevating theoria as the highest calling, reinterpreting it as prayer, meditation, and direct communion with God. At the same time, they emphasized praxis as essential to living out faith, focusing on acts of charity, humility, and service to others. This synthesis of contemplation and action created a balanced spiritual ideal where the pursuit of divine union through theoria was complemented by the ethical demands of praxis, reflecting the integrated life of devotion and service exemplified by Christ.

Eudaimonia

In Greek philosophy, particularly Aristotle’s ethics, eudaimonia referred to human flourishing through the cultivation of virtue and the exercise of reason, representing the highest good a person could achieve in life. Aristotle envisioned eudaimonia as a state of fulfillment rooted in living a life of moral excellence and rational activity in harmony with one’s nature. Christianity reframed this concept, shifting the focus from earthly flourishing to eternal salvation. Spiritual fulfillment became the ultimate goal, attainable not through human effort alone but through divine grace. While retaining the emphasis on virtue, Christian theology subordinated it to faith and the transformative relationship with God, thus redefining the ultimate purpose of life in terms of communion with the divine rather than personal or societal excellence.

Metanoia (Transformation)

Greek metanoia referred to a change of mind or perspective, often tied to a transformative intellectual realization in philosophical contexts. In Christianity, it evolved into the theological concept of repentance, signifying not just a change in thought but a profound spiritual transformation and a turning back to God. This Christian reinterpretation imbued metanoia with moral and relational dimensions, framing it as an essential step in the process of salvation. Through repentance, individuals were called to acknowledge their sins, seek divine forgiveness, and realign their lives with God’s will, emphasizing both personal accountability and divine grace.

Anamnesis (Remembrance)

In Platonic thought, anamnesis involved recollection of eternal truths that the soul had known before its incarnation but had forgotten upon entering the material world. It was a process of intellectual and spiritual awakening, leading one back to the eternal realities of the divine realm. Christianity adopted this concept and gave it a liturgical and salvific dimension, particularly in the Eucharist. Here, anamnesis became a sacred act of remembering Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection, not merely as an intellectual recollection but as a profound spiritual participation in the redemptive work of Christ. This reinterpretation transformed anamnesis into a communal and sacramental practice that united believers with the divine through worship and thanksgiving.

Agape vs. Eros

Greek distinctions between agape (selfless love) and eros (desirous love) profoundly shaped Christian theology and its understanding of divine and human relationships. In Greek philosophy, eros often represented a passionate longing or desire, frequently tied to beauty and the pursuit of the divine, as seen in Plato’s Symposium. Agape, on the other hand, was understood as a more selfless, unconditional love, often tied to the good of others. Christianity elevated agape as the highest form of divine love, interpreting it as the love God has for humanity and the love humans are called to embody toward one another. Eros, while not entirely discarded, was reinterpreted in a spiritual context, emphasizing a longing for union with God rather than physical or worldly desire. This transformation reflected the Christian focus on sacrificial love and the renunciation of purely earthly passions, aligning human love with divine purpose and eternal fulfillment.

Ekstasis

The Greek concept of ekstasis as standing outside oneself to commune with the divine was central to mystical and religious traditions in Greek thought, particularly in the context of experiencing the divine directly. In Neoplatonism, ekstasis often referred to the soul’s ability to transcend the physical and intellectual realms, entering a state of union with the ineffable One. Christianity adopted and expanded this idea, making ekstasis a hallmark of mystical theology. In Christian mysticism, it described transcendent experiences of union with God achieved through prayer, contemplation, and divine grace. Figures such as Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross later elaborated on ekstasis as the ultimate spiritual encounter, where the soul is overwhelmed by God’s presence, stepping beyond earthly concerns and fully engaging with the divine mystery.

Sophia

In Greek thought, Sophia represented divine wisdom, often personified as a guiding and organizing principle of the cosmos. In Platonic and later Neoplatonic traditions, Sophia was linked to the intellectual pursuit of truth and the contemplation of eternal realities. Christianity adopted and expanded this concept, particularly in Eastern Orthodox theology, where Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) came to symbolize divine knowledge, truth, and the active presence of God in creation. This personification of Sophia was not merely philosophical but deeply theological, reflecting the relational and salvific aspects of God’s wisdom. In Christian liturgical traditions, Sophia was often associated with Christ, who was described as the “Wisdom of God” in the New Testament, thereby uniting the abstract concept of wisdom with the incarnate Logos.

The Forms

Plato’s theory of The Forms, rooted in his principle of Ideas (ἰδέαι or εἶδος), posits that beyond the physical world lies a realm of eternal, unchanging archetypes that serve as the perfect models for all things in the material world. In this framework, material objects and experiences are merely imperfect reflections of these transcendent Forms. Christian theology absorbed this concept by equating Plato’s Form of the Good with God as the highest and absolute Good, adapting the idea of Forms to theological doctrines concerning divine perfection, heaven as the ultimate reality, and moral absolutes.

This Platonic influence is particularly evident in Augustine’s writings, where he describes God as the highest and purest reality, mirroring Plato’s Form of the Good. The distinction between the material and the eternal reinforced Christian eschatology, shaping the belief that salvation involves transcending the impermanent physical world to attain unity with the divine. Heaven, like the Platonic realm of Forms, was seen as the true, unchanging reality, superior to the transient and imperfect physical world. This transformation aligned with Christian theological narratives of perfection, emphasizing the contrast between the fallen material realm and the eternal divine presence.

Greco-Roman philosophical concepts and their Christian adaptation (overview)

The following table summarizes key Greco-Roman philosophical concepts and their adaptation within Christian theology, illustrating the transformative process by which Christianity integrated and reinterpreted these ideas to form a comprehensive theological framework:

| Greco-Roman concept | Philosophical school | Christian Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| The One | Neoplatonism | Reimagined as the personal, relational Christian God engaging with creation. |

| Logos | Stoicism, Neoplatonism | Identified as Christ, embodying divine reason and acting as mediator between God and humanity. |

| The nous | Aristotle, Neoplatonism | Reinterpreted as human capacity for divine truth, tied to being made in God’s image. |

| Theosis | Neoplatonism | Reframed as the process of becoming like God through grace and sanctification, accessible to all believers. |

| The demiurge | Platonism | Absorbed into the singular Creator God, rejecting Platonic dualism. |

| Absence of good | Neoplatonism | Adapted as “privatio boni”, explaining evil as a lack of goodness in God’s creation. |

| Oikeiosis | Stoicism | Expanded into the Christian ideal of universal love (agape). |

| Stoic virtue | Stoicism | Integrated into Christian moral theology alongside theological virtues like faith, hope, and love. |

| Dogma | all Greco-Roman philosophical schools | Formalized in Christian creeds and councils to ensure orthodoxy and unity. |

| The tripartite soul | Platonism | Adapted by Augustine to explain human inner struggle between spirit, reason, and flesh. |

| Emanation | Neoplatonism | Reinterpreted within a personal creator-creation relationship with emphasis on grace and redemption. |

| Providence (pronoia) | Stoicism | Transformed into the doctrine of divine providence, emphasizing God’s personal care for creation. |

| Apokatastasis | Stoicism, Neoplatonism | Christianized by Origen as the idea of ultimate restoration of creation, though later controversial. |

| Ethical asceticism | Stoicism, Neoplatonism | Centered on self-discipline as an imitation of Christ’s self-sacrifice and submission to God. |

| Teleology | Aristotelian philosophy | Applied to divine design and humanity’s purpose in creation and salvation. |

| Logos spermatikos | Stoicism | Reimagined by Justin Martyr as Christ manifest in creation and salvation history. |

| Immortality of the soul | Platonism | Accepted but redefined, rejecting preexistence while aligning with resurrection theology. |

| Hylomorphism | Aristotelian philosophy | Used in debates on resurrection to affirm unity of body and soul. |

| Virtue ethics | Aristotle, Stoicism | Combined with theological virtues to form a Christian moral framework. |

| Pater familias | Roman culture | Influenced Christian familial and ecclesial roles, portraying God as “Father”. |

| Natural law | Stoicism, Cicero | Integrated as divine law, reflecting reason and conscience as gifts from God. |

| Civic virtue | Roman culture | Extended into teachings on charity, social justice, and responsibility to the common good. |

| Theoria | Plato, Aristotle | Reinterpreted as prayerful contemplation leading to divine union. |

| Katabasis and anabasis | Neoplatonism | Used to describe Christ’s incarnation and humanity’s ascent to divine union. |

| Mystery religions | Greco-Roman mystery cults | Influenced sacramental theology, particularly baptism and the Eucharist. |

| Eudaimonia | Aristotle | Replaced by eternal salvation as the ultimate goal of human existence. |

| Metanoia | General Greek thought | Transformed into repentance, emphasizing spiritual transformation and returning to God. |

| Anamnesis | Platonism | Reinterpreted as sacred remembrance in Christian liturgy, especially the Eucharist. |

| Agape vs. Eros | General Greek thought | Elevated agape as divine, selfless love; eros reinterpreted as longing for union with God. |

| Ekstasis | Neoplatonism | Central to Christian mysticism, describing transcendent union with God. |

| Sophia | Platonism, Neoplatonism | Became central in Eastern Orthodoxy as divine wisdom (Hagia Sophia) and linked to Christ. |

| The Forms | Platonism | Influenced ideas of divine perfection, heaven, and God as the ultimate Good. |

In summary, Christian theology, in its fully developed form, is indeed deeply rooted in Greco-Roman philosophical traditions. The synthesis of pre-existing philosophical ideas with Jewish religious motifs enabled Christianity to construct a comprehensive theological framework that resonated with the intellectual and cultural milieu of the ancient world. By adapting and reinterpreting key concepts from Neoplatonism, Stoicism, Platonism, and Aristotelianism, Christianity created a theological system that was intellectually robust, morally compelling, and spiritually transformative, appealing to a diverse audience and enabling its rapid expansion and influence.

Let’s briefly summarize and group the core philosophical foundations that Christianity has integrated and reinterpreted to form its theological framework:

Neoplatonic influence

Christian metaphysics is heavily shaped by Neoplatonism, particularly its hierarchical structure of reality, the nature of divine unity, and the process of spiritual ascent. The concept of the One, which in Neoplatonism serves as the ineffable source of all being, was adapted into the Christian doctrine of a singular, omnipotent God. Emanation, central to Plotinus’ metaphysics, influenced early Christian thinkers who envisioned creation as a structured, hierarchical order emanating from God’s divine presence.

Similarly, the Neoplatonic idea of theosis, where the soul strives toward unity with the divine through contemplation, was reinterpreted in Christian theology as the process of sanctification through grace. Privatio boni, the notion that evil is merely the absence of good, was adopted from Neoplatonic thought and incorporated into Augustine’s theology to address the problem of evil without compromising divine omnipotence.

Stoic influence

Stoicism contributed significantly to Christian ethics and theological anthropology. The Stoic interpretation of the Logos, the rational principle governing the universe, was transformed into a central Christian doctrine, identifying Jesus as the incarnate Logos (John 1:1), the divine reason that mediates between God and creation. The Stoic emphasis on virtue, self-discipline, and mastery over passions was absorbed into Christian ascetic practices, influencing monastic traditions and moral teachings.

Furthermore, pronoia (divine providence) in Stoicism, which describes a rational, purposeful order to the cosmos, became the Christian doctrine of divine providence, with God’s governance depicted as both rational and personal. The Stoic notion of oikeiosis, the natural inclination toward care and moral responsibility, was expanded into the Christian idea of agape, universal selfless love.

Platonic influence

Platonic thought, particularly from Plato and his followers, shaped Christian ideas of the soul, virtue, and the nature of reality. Plato’s theory of anamnesis, which described the soul’s recollection of eternal truths, found its way into Christian sacramental theology, particularly in the Eucharistic remembrance (anamnesis). The tripartite soul, which Plato described as consisting of rational, spirited, and appetitive parts, was adopted by Augustine to explain the human struggle between sin, reason, and divine will.

Moreover, the Platonic doctrine of dualism, which distinguishes between the material and the immaterial, influenced Christian eschatology, reinforcing the notion that the body is perishable while the soul aspires to an eternal existence. This philosophical background shaped Christian teachings on resurrection, heaven, and the afterlife.

Aristotelian influence

While Neoplatonism and Stoicism had a stronger immediate impact on early Christianity, Aristotelian philosophy later became crucial in Christian scholasticism, especially through the works of Thomas Aquinas. Teleology, Aristotle’s concept of everything having a final purpose (telos), was integrated into Christian theology to explain divine design and the ultimate goal of human existence — union with God.

Aristotle’s hylomorphism, the theory that all beings are composed of form and matter, was employed to explain the unity of body and soul, particularly in discussions on the resurrection. His system of virtue ethics, which emphasized developing moral character, was synthesized with Christian moral teachings to form the foundation of Christian ethical thought, particularly in defining the cardinal virtues of prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude.

Christian theology as a construct of Greek philosophy

From its cosmology to its ethics, from its metaphysical doctrines to its understanding of human nature, nearly all aspects of Christian theology can be traced back to pre-existing Greek philosophical traditions. Neoplatonism provided the metaphysical structure, Stoicism shaped Christian ethics, Platonism influenced its doctrines of the soul and salvation, and Aristotelianism refined its moral and teleological arguments.

Though Christianity introduced some distinct theological concept — such as the Incarnation, the Trinity, and the specific redemptive role of Christ — these ideas were framed within the intellectual vocabulary and conceptual structures inherited from Greco-Roman thought. The Church Fathers and later Christian theologians systematically absorbed, reinterpreted, and refined Greek philosophical principles, constructing a theological framework that was intellectually robust and capable of engaging with the dominant philosophical schools of the Greco-Roman world.

Thus, it is evident that Christian theology is fundamentally a synthesis of Neoplatonic, Stoic, Platonic, and Aristotelian philosophy, adapted and reframed through a Jewish religious lens. This intellectual adaptation was instrumental in Christianity’s evolution from a marginal local Jewish apocalyptic sect into a structured theological system that resonated with the Greco-Roman intellectual and cultural environment. In this light, Christian theology emerges not as an entirely independent creation but as a Greco-Roman intellectual construct, reframed within a new religious and cultural framework to ensure its broad appeal and endurance.

Christianity’s pragmatic adaptability

Christianity’s ability to adapt and absorb elements of local cultures while maintaining a core set of dogmas further underscores its engineered flexibility. For example:

Hellenization

Early Christian thinkers like Origen and Augustine reinterpreted Jesus’ teachings through a Greco-Roman lens, making them palatable to the intellectual elite. They integrated concepts such as the Logos (borrowed from Stoicism and Neoplatonism) into Christian theology, framing Jesus as the divine rational principle that underpins the universe. This intellectualization allowed Christianity to gain credibility among educated classes while retaining its core message of salvation.

Romanization

After Constantine’s conversion, Christianity adapted to imperial structures, becoming the state religion and adopting elements of Roman bureaucracy. The hierarchical organization of the Church mirrored the administrative structure of the Roman Empire, with bishops and archbishops resembling provincial governors. Furthermore, Constantine’s endorsement led to the use of Roman legal and cultural norms in defining orthodoxy, facilitating the Church’s integration into the imperial system.

Cultural localization

Over time, Christianity assimilated pagan festivals, symbols, and practices, such as Christmas and Easter, transforming them into distinctly Christian celebrations. These adaptations were strategic, repurposing local customs to make Christianity more familiar and acceptable to diverse populations. For instance, the celebration of Christ’s birth on December 25 aligned with Roman Saturnalia and other winter solstice traditions – and with the birth of the sun god Sol Invictus –, easing the transition from paganism to Christianity while maintaining continuity in cultural rituals.

The role of dogma in maintaining the system

Ironically, while Christianity’s “engineered” nature allowed it to grow and thrive, its survival has depended on the rigid enforcement of dogma. Dogmas serve as the glue that holds this artificial construct together by ensuring unity, theological coherence, and institutional control while suppressing dissent and diversity.

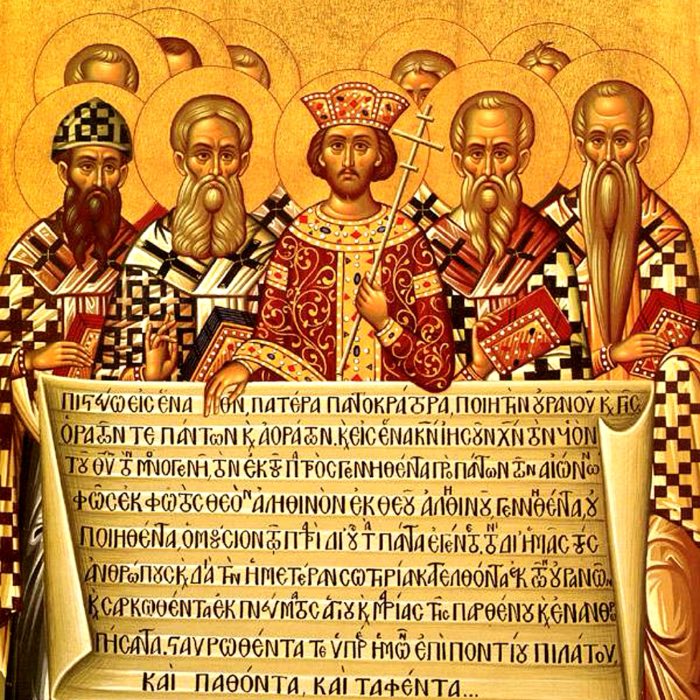

Theological coherence

Christianity’s core doctrines — such as the Trinity, the Incarnation, and salvation through Christ — are the product of intricate theological debates and compromises. These doctrines often emerged as responses to internal divisions or external challenges. For example, the Nicene Creed was a direct response to Arianism, which questioned the divine status of Jesus. The Trinity, which unites God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit into one Godhead, resolved competing theological interpretations while creating a unifying framework for believers.

The codification of these doctrines into creeds and councils was essential for maintaining theological coherence. Without these systematic efforts, the diversity of early Christian beliefs might have fractured the movement into irreconcilable sects. By imposing a clear and unified narrative, the Church provided a stable theological foundation that could be propagated across the Roman Empire and beyond.

Control of interpretation

Declaring alternative interpretations heretical was another key strategy in maintaining Christianity’s structure. Early challenges, such as Gnosticism and Arianism, presented alternative visions of Christ and salvation that might have undermined the Church’s authority and unity. Gnosticism, for instance, emphasized personal spiritual knowledge over ecclesiastical authority, while Arianism denied Christ’s equality with God.

By branding these movements heretical, the Church not only suppressed theological diversity but also solidified its position as the sole arbiter of truth. Councils such as those of Nicaea (325 CE) and Chalcedon (451 CE) institutionalized this authority, defining orthodoxy and marginalizing dissenters. This suppression of dissent extended to broader intellectual traditions, as seen in the gradual decline of philosophical pluralism in the Roman world.

Emotional and social stability

Dogmas also provided emotional certainty and social cohesion. The promise of salvation through Christ, the clear moral framework offered by Christian teachings, and the assurance of divine justice gave believers a sense of purpose and belonging. In a world marked by political instability, economic uncertainty, and frequent crises, Christianity’s dogmatic framework offered a source of hope and consistency.

This emotional stability was reinforced by the communal rituals and practices tied to dogma. The sacraments, such as baptism and the Eucharist, were not only spiritual but also social acts that bound communities together and provided a framework for communal identity and solidarity. By framing dogmas as divinely revealed and unchanging, the Church created a sense of permanence that could withstand societal upheavals.

Dogma vs. faith

While faith is often emphasized as central to Christianity, it is probably the intricate web of dogmas that holds the system together. Dogmas were not organically derived but meticulously developed through centuries of debate, controversy, and deliberate decisions to ensure a unified orthodoxy and to maintain institutional control. The tension between personal faith and doctrinal adherence has been a recurring theme in Christian history, with the latter often taking precedence in shaping the Church’s identity and boundaries.

Conclusion

Christianity is a remarkable synthesis of Jewish religious traditions and Greco-Roman philosophical ideas, meticulously constructed to address the cultural and political realities of its time. By absorbing and reinterpreting preexisting concepts, it created a theological framework capable of appealing to diverse audiences while consolidating institutional power. However, its adaptability and reliance on dogma expose its engineered nature. Every religion evolves and adapts, but Christianity’s deliberate construction — centered around the Jesus mystery cult and reinforced by Greco-Roman intellectual traditions — stands out for its systemic nature. While the question of whether Christianity is the “most engineered” religion remains rhetorical, its history offers a striking example of how theological systems are shaped less by divine revelation than by cultural necessity and power dynamics. In this sense, Christianity reflects the universal truth that religion is as much a human construct as it is a spiritual pursuit.

After reviewing the origins of Christianity’s central theological concepts — such as the Logos, virtue ethics, and even the idea of the soul’s divine ascent — it is worth questioning whether the modern Western world is truly living in a “Christian” culture. Many of the ideas considered foundational to Western thought and morality are not inherently Christian but rather Greek or Roman in origin, absorbed and repurposed by Christian theology. Concepts like rationality, natural law, and civic virtue have deeper roots in ancient Greek philosophy and -roman traditions than in the teachings of Jesus (which were themselves influenced by Jewish prophetic traditions and pre-existing Hellenistic thought). The Roman Empire further contributed to the administrative and institutional structures that continue to influence modern governance. While Christianity played a critical role as a vehicle for transmitting and adapting these ideas, the cultural and intellectual foundations of Europe and the Western world are undeniably shaped by Greek and Roman heritage. Thus, what we often call “Christian culture” might more accurately be described as the legacy of a Greco-Roman civilization reframed through a Jewish-Christian lens.

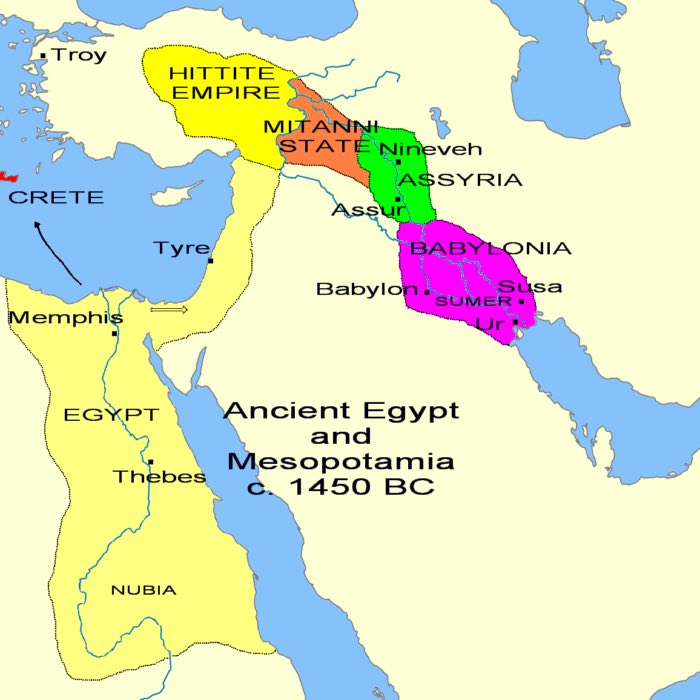

While the intellectual legacy of Christianity is undeniable, one must also consider the consequences of its exclusivist theological framework. The belief in absolute truth, coupled with the rejection of alternative perspectives, led to centuries of intolerance, sectarian conflict, and religious warfare. A system built upon Greco-Roman philosophical rationality could have flourished in a more inclusive and pluralistic manner had it not been burdened with its own dogmatic rigidity and exclusivist salvific claims. If history had allowed for a coherent philosophical system rooted purely in Greek intellectual traditions, without the additions of Jewish-Christian dualism – which were itself rooted in other Mesopotamian and Egyptian religious traditions such as Zoroastrianism and Osiris cult – and the assertion of a singular, exclusive religious truth — an ideology that fostered the suppression of alternative views and, in many cases, the systematic persecution and elimination of dissenters —, the Western intellectual and moral tradition might have evolved in a more open and inclusive direction — one less defined by religious dogmatism and more by philosophical inquiry, ethical reasoning, and genuine pluralism – and eventually with less religiously motivated astrocities and catastrophes.

References and further reading

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Ehrman, Bart D., The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World, 2019, Oneworld Publications, ISBN: 978-1786074836

- Panagiotis G. Pavlos, Lars Fredrik Janby, Eyjólfur Kjalar Emilsson, Torstein Theodor Tollefsen, Platonism and Christian Thought in Late Antiquity, 2021, Routledge, ISBN: 978-1032092003

- Brother Azarias, Aristotle and the Christian Church, 2024, Henderson Publishing, ISBN: 979-8896350330

- Joseph Grogan, Christian Orthodoxy: A Closer Look, 2024, Joseph Grogan, ISBN: 979-8218234799

- Long, A. A., Hellenistic philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics, 1986, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520058088

- Pelikan, Jaroslav, The Christian tradition: A history of the development of doctrine, Volume 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), 1975, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226653716

- Pelikan, Jaroslav, The Christian tradition: A history of the development of doctrine, Volume 2: The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600-1700), 1977 University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226549330

- Pelikan, Jaroslav, The Christian tradition: A history of the development of doctrine, Volume 3: The Growth of Medieval Theology (600-1300), 1980 University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226653754

- Pelikan, Jaroslav, The Christian tradition: A history of the development of doctrine, Volume 4: Reformation of Church and Dogma (1300-1700), 1985 University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226653778

- Pelikan, Jaroslav, The Christian tradition: A history of the development of doctrine, Volume 5: Christian Doctrine and Modern Culture (since 1700), 1991 University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226653808

- Karlheinz Deschner, Serie: Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, zehn Bände, Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986ff:

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 1 Die Frühzeit, 1996, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012632

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 2 Die Spätantike, 1996, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499601422

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 4 Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 5 von Ludwig dem Frommen (814) bis zum Tode Ottos III. (1002). 9. und 10. Jahrhundert, 1998, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499605567

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 6 11. und 12. Jahrhundert: Von Kaiser Heinrich II., dem “Heiligen” (1002), bis zum Ende des Dritten Kreuzzugs (1192) (1986)s, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498013097

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 7 12. und 14. Jahrhundert: Von Kaiser Heinrich VI. (1190) zu Kaiser Ludwig IV. dem Bayern (1347), 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498013202

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 9 -Mitte des 16. bis Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vom Völkermord in der Neuen Welt bis zum Beginn der Aufklärung, 2010, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499624438

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 10 18. Jahrhundert und Ausblick auf die Folgezeit. Könige von Gottes Gnaden und Niedergang des Papsttums, 2014, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499630200

- Karlheinz Deschner, Hubert Mania, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums 1-10: Sachregister und Personenregister, 2014, Rowohlt, Reinbek, ISBN 978-3-499-63055-2

- Hellmut Flashar, Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 1. Frühgriechische Philosophie, 2013, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796525988

- Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 2/1. Sophistik, Sokrates, Sokratik, Mathematik, Medizin, 1998, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796510366

- Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 2/2. Platon, 2007, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-2237-6

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Christoph Riedweg, Christoph Horn, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 5. Die Philosophie der Kaiserzeit und der Spätantike, 2018, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796526299

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- John Marenbon, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 2. 11. Jahrhundert, 2025, Schwabe Verlag, ISBN: 9783796526251

- Laurent Cesalli, Ruedi Imbach, Alain de Libera, Thomas Ricklin, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 3. 12. Jahrhundert, 2021, Schwabe Verlag, ISBN: 9783796526251

- Alexander Brungs, Vilem Mudroch, Peter Schulthess, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 4. 13. Jahrhundert, 2017, Schwabe, ISBN: 9783796526268

comments