Shestodnev icons: The six-day work of God

The Shestodnev (Six-Day) icon emerged in the late 15th century, embodying a theological synthesis of the biblical narrative of creation and the liturgical rhythms of Christian worship. Its development coincided with the eschatological concerns of the era, particularly as the year 1492 – believed to mark 7,000 years since the creation of the world – drew near. At this time, many Christians sought to comprehend not only their personal salvation but also the divine economy guiding humanity and the Church’s role within it. The Shestodnev icon became a visual testament to these inquiries, combining symbolic representations of Genesis, sacred history, and the liturgical week.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Origins and eschatological context

In the late medieval period, eschatological anticipation surged as the year 1492 approached, a date interpreted in some traditions as the culmination of 7,000 years since the creation of the world. This belief inspired a renewed focus on understanding God’s cosmic plan, humanity’s place within it, and the unfolding of salvation history. Icons like the Shestodnev sought to encapsulate these themes in a rich visual narrative.

The term Shestodnev refers to the six days of creation (Greek: Hexaemeron) as recounted in the Book of Genesis. However, these icons go beyond the literal depiction of creation to explore the interplay between the biblical narrative, liturgical practices, and the redemptive acts of Christ. Through their intricate compositions, Shestodnev icons offered believers a way to contemplate the mysteries of faith and the progression of God’s work from creation to the eschaton.

Structure and composition of the icon

The Shestodnev icon is a composite work, often described as “many icons in one”. Its central focus is the biblical account of creation, depicted in a sequence of six days according to Genesis 1. Surrounding this core are additional scenes and figures that expand the theological scope of the icon, linking creation to redemption and sanctification.

-

Central imagery: Usually, the depiction of the six days of creation forms the nucleus of the icon. Each day is illustrated with vibrant imagery corresponding to the Genesis account, portraying the divine act of bringing order to chaos and populating the world with life. This motif can of course vary, e.g., by depicting Jesus, the logos, as the Creator, or the Synaxis (gathering) of the angels.

- Scenes from sacred history: Alongside the central motif, Shestodnev icons frequently include pivotal moments in salvation history, such as:

- The Fall of Adam and Eve, emphasizing the origins of sin and humanity’s need for redemption.

- The Annunciation, signifying the Incarnation as the beginning of Christ’s earthly mission.

- The Nativity, Crucifixion, and Resurrection of Christ, encapsulating the redemptive arc of the New Testament.

- Liturgical and ecclesiastical elements: The icon often incorporates the Church’s liturgical calendar, with depictions of saints and events commemorated on specific days of the week. For example:

- Tuesday might feature John the Baptist.

- Thursday could highlight St. Nicholas of Myra. This integration underscores the continuous remembrance of sacred history in the Church’s worship.

- Figures of saints and evangelists: Saints and evangelists are often positioned along the edges or corners of the icon, representing the unity of the Church across time and space. These figures serve as intercessors and witnesses to God’s ongoing work in the world.

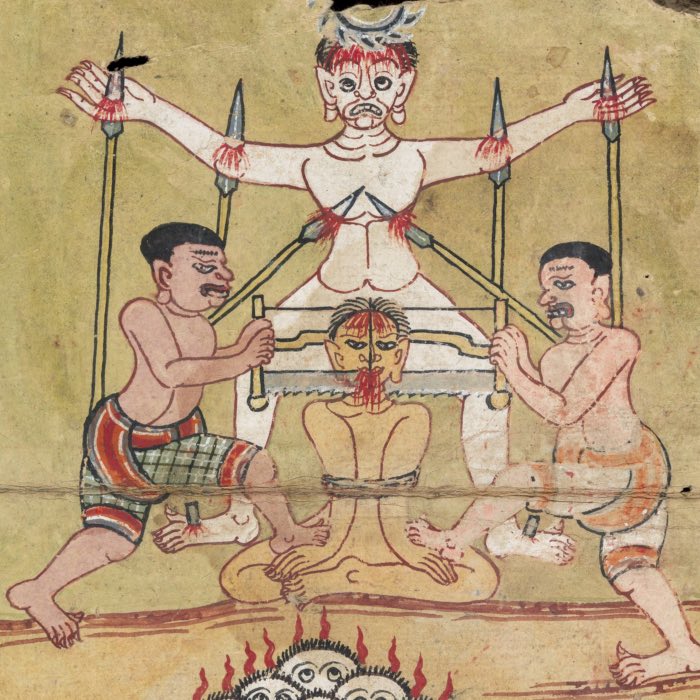

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Six-day work of God (Shestodnev) (detail), Russia, 18th century, tempera on canvas and wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Theological and symbolic significance

The Shestodnev icon embodies a dual purpose: it visualizes the biblical creation narrative while simultaneously linking it to the Church’s existence and mission. This duality reflects the theological conviction that creation is not merely an isolated historical event but the foundation of a divine plan fulfilled through Christ and the Church.

By juxtaposing Genesis with scenes of Christ’s life and passion, the icon highlights the unity of God’s salvific work, from the creation of the world to its redemption through the Incarnation and Resurrection.

The inclusion of saints and weekly commemorations connects the cosmic scale of creation to the daily life of the Church, emphasizing the interplay between sacred history and liturgical practice.

The Shestodnev icon serves as a catechetical tool or visual theology, teaching believers about the continuity of God’s work in the world. It invites contemplation of the mysteries of faith through a harmonious blend of color, symbolism, and narrative.

Conclusion

The Shestodnev icon represents a unique synthesis of biblical, liturgical, and eschatological themes, offering an access to the theological concept of God’s work in creation and redemption. Through its intricate composition, it weaves together the Genesis narrative, sacred history, and the rhythms of Christian worship, inviting believers to reflect on the divine economy and the Church’s place within it. As a product of its time, the Shestodnev remains an expression of believes and fears of the late medieval period, encapsulating the yearning for understanding and salvation in a world marked by eschatological anticipation as proclaimed by the Church.

References and further reading

- pravoslavie.wikiꜛ

- Cornelia A. Tsakiridou, Icons in time, persons in eternity – Orthodox theology and the aesthetics of the Christian image, 2020, Routledge, ISBN: 9780367601768

- Klaus-Rainer Althaus, Snejanka Bauer, Karin Kirchhainer, Guntram Koch, Alexandra Neubauer, Richard Zacharuk, Icons: Icon Museum Frankfurt a.M., 2005, Legat Verlag, ISBN: 9783932942198

- Gennady V. Popov, Natalia Chugreeva, Farben der Heiligkeit – Meisterwerke der Ikonenkunst aus dem Andrej-Rubljow-Museum in Moskau, 2013, Druckerei Wirth

- Alexandra Neubauer, .von der Hand Deines Dieners. Christliche Ikonen der arabischen Welt, 2004, Legat Verlag, ISBN: 9783932942198

- Thomas Böhm, Peter Bruns, Wolfram Drews, Michael Durst, Michael Fiedrowicz, Johannes Franzkowiak, Reinhard Meßner, Eckhard Wirbelauer, Gerhard Philipp Wolf, Die Geschichte des Christentums – Der lateinische Westen und der byzantinische Osten (431-642), 2005, Herder, Ungekürzte Sonderausgabe, Hrsg.: Norbert Brox, Jean-Marie Mayeur, Charles Piétri, ISBN: 9783451291005

- Manolis Chatzidakis, Naxos. Byzantine Art in Greece, 1989, MELISSA Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9602040461

- Arne Effenberger, Hans-Georg Severin, Das Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst, 1992, Herausgeber: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, ISBN: 9783805311854

- Volbach, Wolfgang Fritz, and Lafontaine-Dosogne, Jacqueline, Byzanz und der christliche Osten, 1990, Serie: Propyläen Kunstgeschichte, Propyläen Verlag, Frankfurt am Main

- Denis Walter, Michael Psellos: Christliche Philosophie in Byzanz - Mittelalterliche Philosophie im Verhältnis zu Antike und Spätantike, 2017, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, ISBN: 9783110526028

- Irmgard Hutter, Frühchristliche und byzantinische Kunst - Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, 1991, München: Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, ISBN: 9783763018741

- Georgi Kapriev, Philosophie in Byzanz, 2005, Königshausen & Neumann, ISBN: 9783826026676

- Wladimir Sas-Zaloziecky, Die byzantinische Kunst, 1963, Serie: Ullstein Kunstgeschichte, Verlag Ullstein

- Benjamin Fourlas, Wege nach Byzanz, 2011, Verlag Leibniz-Zentrum für Archäologie (LEIZA), ISBN: 9783884671863

- Arne Effenberger, Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger, Byzanz - Kunst und Kultur, 2017, C.H.Beck, ISBN: 978-3406587023

- Peter Schreiner, Byzanz 565-1453, 2011, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, ISBN: 9783486702712

- André Grabar, Byzanz - die byzantinische Kunst des Mittelalters (vom 8. bis zum 15. Jahrhundert), 1976, Holle, ISBN: 9783873551251

- Wikipedia article on iconsꜛ

- Website of the Icon Museum Frankfurtꜛ

comments