The role of icons in Orthodox believes

Orthodox icons, derived from the Greek word eikṓn meaning “image” or “likeness”, play a foundational role in the faith, theology, and worship of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Far from being decorative objects, icons are viewed as sacred tools of devotion, offering believers a tangible connection to the divine. Often described as “windows to heaven”, icons serve as both theological affirmations and personal aids in spiritual practice. Their rich history, theological significance, and symbolic artistry distinguish them from other forms of Christian art, underscoring their profound role in Orthodox beliefs. I recently visited the Icon Museum in Frankfurtꜛ, where I had the opportunity to explore and appreciate original Orthodox icons.

St. Nicholas (detail; full view below), Russia, 19th century (detail), egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicholas (detail; full view below), Russia, 19th century (detail), egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Historical foundations in Orthodox beliefs

Orthodox iconography has a rich history spanning over 1,500 years, intricately tied to theological, cultural, and political developments in the Christian East. Its evolution reflects a remarkable synthesis of continuity and change, as icons retained their spiritual significance while adapting to historical and regional contexts.

Early Christian foundations and late antiquity

The roots of Orthodox iconography lie in the artistic traditions of the Greco-Roman world, which provided both visual inspiration and technical foundations. Early Christian art drew from late antique practices such as funerary portraiture, imperial imagery, and pagan religious art. These traditions, reinterpreted through a Christian lens, laid the groundwork for the emergence of sacred imagery.

The oldest surviving icon of Christ Pantocrator, encaustic on panel, c. 6th century, Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The oldest surviving icon of Christ Pantocrator, encaustic on panel, c. 6th century, Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

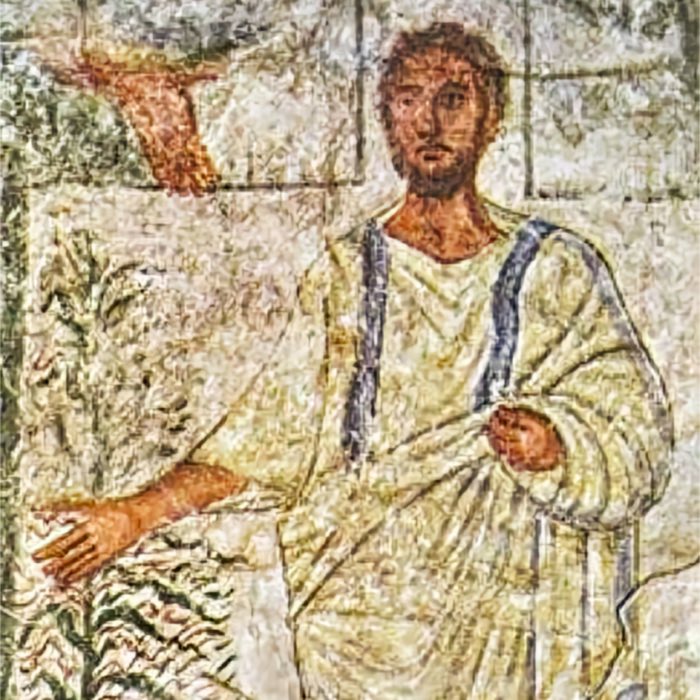

Funerary portraiture, such as the Fayum portraits of Roman Egypt, influenced early Christian depictions of saints and martyrs. Painted on wooden panels using encaustic or tempera techniques, these portraits conveyed a sense of spiritual presence that was later adopted in iconography. Similarly, imperial imagery, which portrayed emperors as divine or semi-divine figures, informed the early Christian representation of Christ as Pantocrator, emphasizing his cosmic sovereignty.

Christ and Saint Menas, 6th-century Coptic icon from Egypt, Musée du Louvre. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Christ and Saint Menas, 6th-century Coptic icon from Egypt, Musée du Louvre. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Pagan religious art also shaped early iconography. Unlike pagan cult images, which were believed to embody the divine, Christian icons were understood as representations that facilitated connection with the divine without being equated with it. This distinction became a cornerstone of the theological justification for icons in the early Church.

By the 4th century, with Christianity established as the state religion under Constantine the Great, sacred art gained prominence in worship. Churches began incorporating Christian symbols and narrative scenes, setting the stage for the development of Byzantine iconography.

Byzantine formulation and the birth of the icon

Byzantium, as the continuation of the Roman Empire in the East, provided the environment for iconography to mature into a distinct art form. The 6th century marked a turning point as icons assumed their characteristic theological and aesthetic features.

Theologically, the doctrine of the Incarnation was foundational. The belief that God became visible in the person of Jesus Christ legitimized the depiction of the divine. Icons of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints were seen as affirmations of this profound truth.

Artistically, Byzantine icons departed from naturalism, favoring symbolic representation. Gold leaf backgrounds symbolized divine light, while inverse perspective conveyed spiritual, rather than physical, realities. These stylistic choices reflected the icons’ purpose: not to mimic the material world but to invite contemplation of the divine.

Icons also became integral to Byzantine worship. Large icons adorned churches, particularly the iconostasis, a screen separating the nave from the sanctuary. Portable icons were used in private devotion and public processions, emphasizing their spiritual and communal importance.

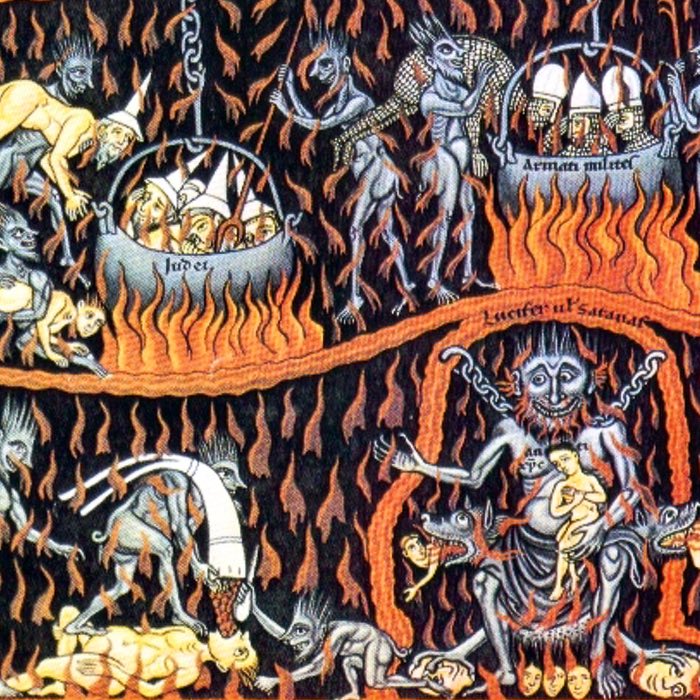

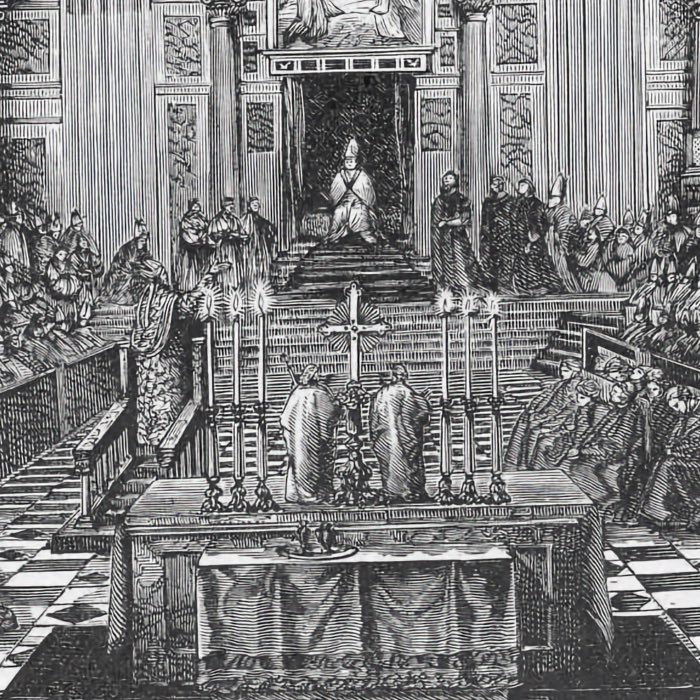

Iconoclastic Controversy (726–843)

The 8th and 9th centuries were marked by the Iconoclastic Controversy, a period of intense theological and political conflict. Iconoclasts, who opposed icons, argued that sacred images violated biblical prohibitions against idolatry. Iconophiles defended icons as essential to Christian worship, emphasizing their role as representations of the Incarnate Word.

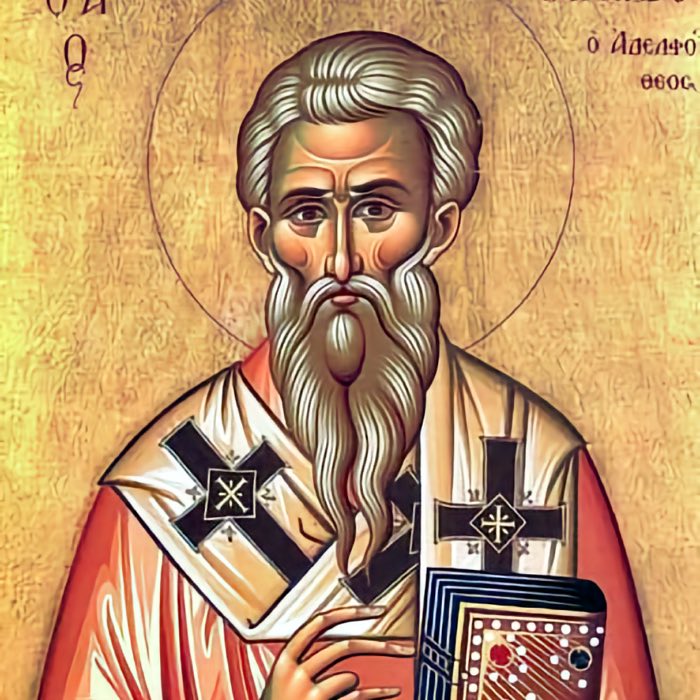

This controversy had profound consequences. Many icons were destroyed, and their veneration was suppressed under emperors like Leo III and Constantine V. However, defenders like St. John of Damascus articulated a robust theological defense, distinguishing veneration from worship and affirming the Incarnation as the basis for sacred imagery.

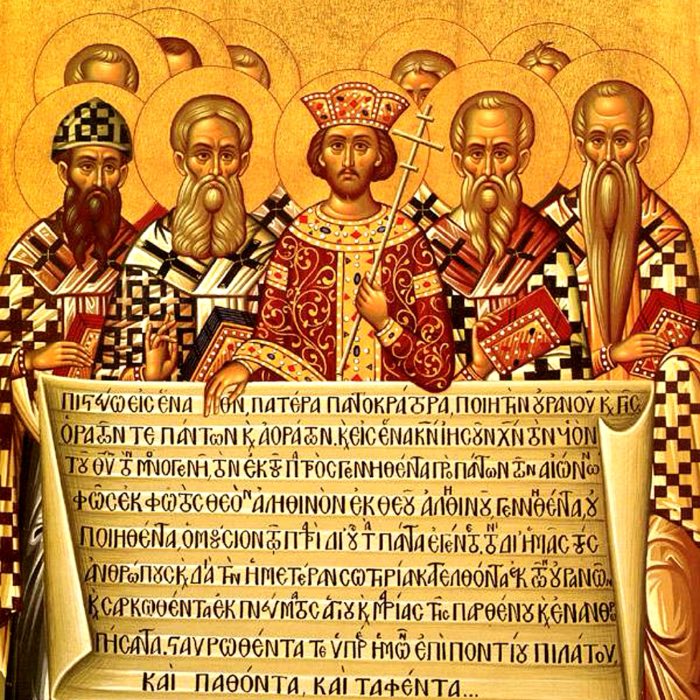

The Second Council of Nicaea (787) resolved the controversy by affirming the legitimacy of icon veneration. The “Triumph of Orthodoxy” in 843 marked the permanent restoration of icons to Orthodox worship.

Golden Age of Byzantine iconography (9th–15th centuries)

With the resolution of the Iconoclastic Controversy, Byzantine iconography entered a golden age. During this period, iconographers refined their techniques and developed new compositions that enriched Orthodox spirituality.

Icons such as the Deesis, depicting Christ flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, became central to liturgical and devotional life. Narrative icons illustrating biblical events and the lives of saints also flourished, emphasizing the connection between sacred imagery and theological teaching.

Portable icons gained prominence, serving as personal devotional objects and important trade items. The export of Byzantine icons influenced Western art, particularly in Italy, where they inspired early Renaissance artists.

Miraculous icons, such as the Hodegetria, became symbols of divine protection, often carried in public processions. Their association with political and spiritual authority reinforced their significance in Byzantine culture.

Post-Byzantine iconography and regional adaptations

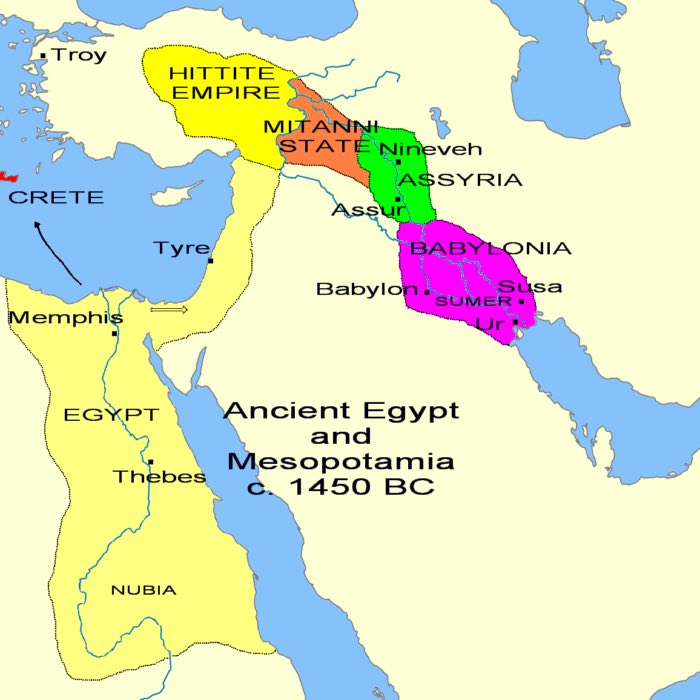

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 marked the end of the Byzantine Empire but not the decline of its artistic legacy. Iconography continued to flourish in Orthodox lands, adapting to local traditions while preserving its theological essence.

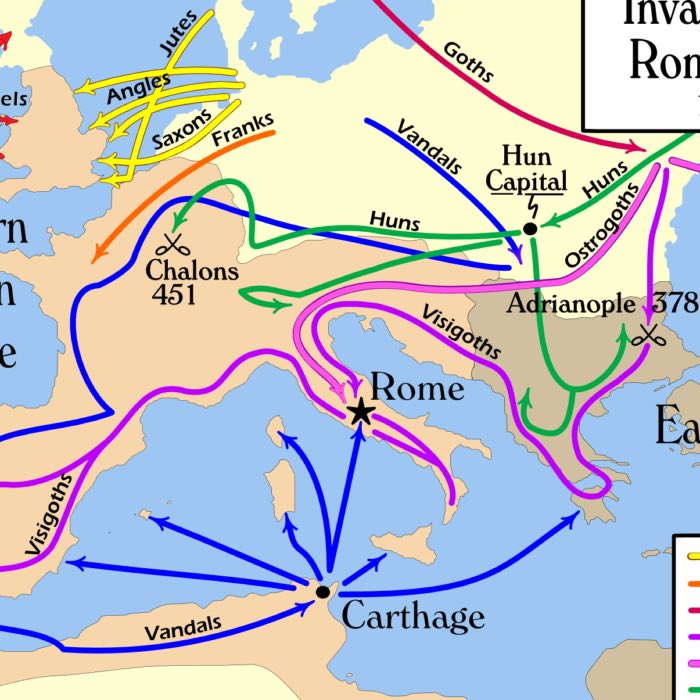

The map of the origins of the exhibited icons in the Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt shows the spreading of Orthodox iconography. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The map of the origins of the exhibited icons in the Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt shows the spreading of Orthodox iconography. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

In Russia, for instance, iconography reached new heights, with schools in Novgorod, Moscow, and Suzdal producing masterpieces that combined Byzantine influence with local innovation. The works of Andrei Rublev, such as his Holy Trinity icon, exemplify the spiritual and artistic sophistication of Russian iconography. Similarly, the Balkans and other Slavic regions developed distinctive styles, reflecting their unique cultural contexts.

In the Mediterranean, the Cretan and Italo-Byzantine schools bridged Eastern and Western traditions, blending Byzantine techniques with Renaissance naturalism. These icons appealed to diverse audiences, demonstrating the adaptability and universality of Orthodox iconography.

The 20th and 21st centuries have witnessed a revival of interest in Orthodox iconography. Contemporary iconographers, inspired by historical models, continue to produce works that adhere to traditional techniques and theological principles.

Symbolism and aesthetic as tools of faith

Orthodox icons are characterized by their unique aesthetic and theological principles, which distinguish them from Western art. Their form and symbolism serve as a visual language associated with the religious and spiritual teachings of the Orthodox Church. Understanding the artistic characteristics of icons is essential to appreciating their role as theological objects.

The Annunciation (detail), Emmanuel Tzanes, Venice, Italian-Cretan, 1640, egg tempera on wood. And the angel said to her: ‘Do not be afraid, Mary! You have found favor with God. Behold, you will conceive and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus.’ - Luke 1, 30-31. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Annunciation (detail), Emmanuel Tzanes, Venice, Italian-Cretan, 1640, egg tempera on wood. And the angel said to her: ‘Do not be afraid, Mary! You have found favor with God. Behold, you will conceive and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus.’ - Luke 1, 30-31. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Icons are traditionally painted on wood panels using tempera or encaustic techniques. Gold leaf backgrounds symbolize divine light and the heavenly realm, while colors such as blue and red represent divine wisdom and martyrdom, respectively.

Tools used in the creation of icons at the Icon Museum in Frankfurt.

Tools used in the creation of icons at the Icon Museum in Frankfurt.

Color pigments used in the creation of icons at the Icon Museum in Frankfurt.

Color pigments used in the creation of icons at the Icon Museum in Frankfurt.

Figures are depicted frontally, emphasizing their spiritual presence. Inverse perspective, where distant objects appear larger, reflects a divine viewpoint and invites the viewer into the sacred space of the icon. This stylistic choice underscores the spiritual rather than physical nature of the depicted reality.

Inside the icon workshop of a Russian monastery, Russia, 2011. All photographs: Gabriele Lentini. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Inside the icon workshop of a Russian monastery, Russia, 2011. All photographs: Gabriele Lentini. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Icons are not static images but dynamic mediators of the divine. Their symbolic composition, gestures, and inscriptions guide the viewer toward contemplation of the sacred.

Theological role of icons

The historical evolution of icons reveals not only their artistic development but also their growing importance as central tools for worship and expressions of Orthodox theology. The theology of icons in Orthodox Christianity is profoundly rooted in the doctrine of the Incarnation and the Orthodox Church’s understanding of the relationship between the material and spiritual worlds. In Orthodox theology, icons are not merely religious art; they are deeply theological objects that embody the mysteries of faith, serving as both visual theology and sacred windows through which believers encounter the divine.

Processional cross, The Archangel St. Michael and the Crucifixion of Christ, Russia, late 19th century, wood, painted on both sides with egg tempera. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Processional cross, The Archangel St. Michael and the Crucifixion of Christ, Russia, late 19th century, wood, painted on both sides with egg tempera. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Incarnation as the foundation of iconography

The doctrine of the Incarnation is the cornerstone of Orthodox iconography. The belief that the Word of God became flesh in the person of Jesus Christ (John 1:14) made the invisible God visible and accessible, providing the theological basis for sacred imagery. Prior to the Incarnation, the Second Commandment (Exodus 20:4–5) forbade the depiction of God, as He was understood to be beyond human comprehension. However, with God’s self-revelation in Christ, the divine entered the material world, making it permissible – and necessary – to represent Christ in visual form.

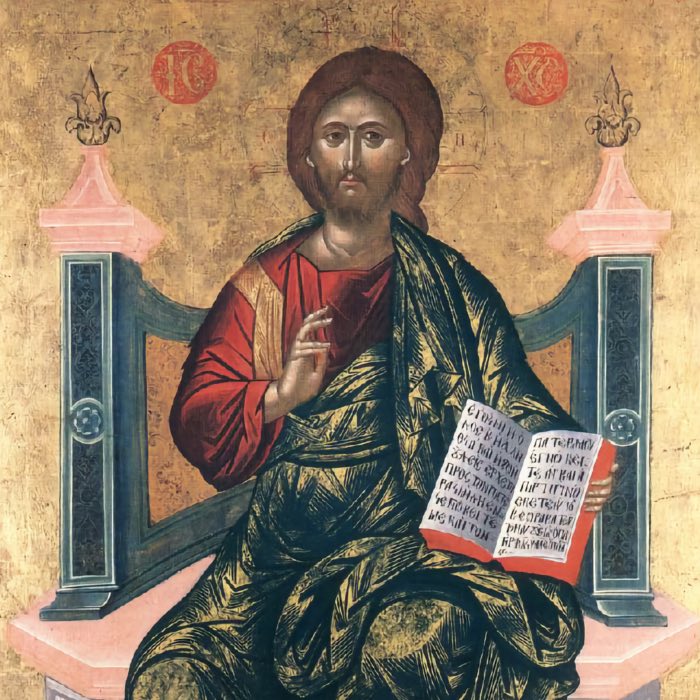

Christ Pantocrator, Greece, 2nd half of 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ Pantocrator, Greece, 2nd half of 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. John of Damascus, a key defender of icons during the Iconoclastic Controversy, articulated this theological foundation. He argued that Christ’s humanity made it possible to depict God without violating the biblical prohibition. For St. John, icons are not merely representations of historical figures but affirmations of the Incarnation, testifying to God’s tangible presence in the world.

This understanding extended to the depiction of saints and the Virgin Mary. Saints, as individuals transformed by divine grace, reflect the image of God within humanity. Marian icons, such as the Theotokos Hodigitria (“She Who Shows the Way”), emphasize Mary’s unique role as the God-bearer, guiding believers to Christ.

Virgin Hodegetria, Greece, 2nd half of 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Virgin Hodegetria, Greece, 2nd half of 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Veneration versus worship

One of the key theological principles in the Orthodox understanding of icons is the distinction between veneration (proskynesis; reverential bowing; acts of deep respect or veneration, such as bowing, crossing oneself, or kissing an icon, directed toward the prototype it represents) and worship (latreia; worship or adoration reserved for God alone; devotion that is exclusively offered to God, as distinct from the reverence shown to saints or holy objects). Worship, or adoration, is reserved for God alone, while veneration is an act of reverence directed toward the prototype – the person or divine reality represented by the icon. This distinction was emphasized in the Second Council of Nicaea (787), which affirmed the legitimacy of icon veneration and clarified that the honor given to an icon passes to its prototype.

This distinction addresses concerns about idolatry, which were central to the arguments of iconoclasts during the Iconoclastic Controversy. Iconophiles maintained that the veneration of icons was not equivalent to the worship of the material object. Instead, icons serve as conduits through which believers express their reverence for Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints.

The veneration of icons involves physical gestures such as bowing, crossing oneself, lighting candles, and kissing the icon. These acts are understood not as directed toward the physical object but as expressions of devotion to the spiritual realities it represents. Icons thus function as visual mediators, linking the faithful with the divine.

Icons as theology in color

Orthodox icons are often described as “theology in color”, reflecting their role as visual expressions of theological truths. Every aspect of an icon, from its composition to its colors and inscriptions, is imbued with symbolic meaning, designed to convey the mysteries of the faith in a way that transcends language.

St. Barbara, Russia, 1st half of 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Barbara, Russia, 1st half of 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The gold background, a hallmark of Orthodox iconography, symbolizes divine light and the eternal nature of God’s kingdom. The figures are stylized and non-naturalistic, emphasizing their spiritual essence rather than their physicality. Inverse perspective, where the vanishing point lies in front of the image, invites the viewer into the sacred space of the icon, creating a sense of participation in the divine reality.

The use of symbolic colors enhances the theological depth of icons. Blue often represents divine wisdom, red signifies martyrdom and sacrifice, and green symbolizes renewal and eternal life. These elements work together to create a visual language that speaks directly to the believer’s heart and mind.

Role of icons in worship and devotion

Icons are deeply integrated into the liturgical and devotional life of the Orthodox Church. In liturgical settings, icons adorn the iconostasis, the screen separating the nave from the sanctuary, and are integral to the visual and symbolic narrative of the church. The iconostasis typically features a central depiction of Christ Pantocrator and the Virgin Mary, flanked by images of saints and biblical events. This arrangement serves as a visual representation of the heavenly court and the communion of saints.

Icons are also used in processions, where they are carried through the streets or within the church as acts of public devotion and prayer. These processions often commemorate significant feasts or events in the life of the Church, reinforcing the communal and celebratory aspects of Orthodox worship.

In private devotion, icons occupy a central place in the prayer corners of Orthodox homes. These spaces, often oriented toward the east, serve as a locus for daily prayer and contemplation. Icons in this context provide a tangible focus for the believer’s spiritual practices, offering a sense of continuity between the liturgical life of the church and personal piety.

Icons as mediators of the divine

A distinctive feature of Orthodox theology is its understanding of icons as mediators of the divine presence. This concept is rooted in the belief that the material world, though fallen, can serve as a vessel for divine grace. Through the Incarnation, the material and the spiritual are united, and icons participate in this sacramental reality. The wood and paint of the icon are sanctified through the prayers of the Church, enabling the icon to become a vessel of divine presence.

The miraculous properties often attributed to certain icons, such as healing or protection, further illustrate this theological principle. While these properties are not inherent to the material object itself, they are understood as manifestations of God’s grace working through the icon. Such icons, often called “wondrous” or “miraculous”, hold a special place in the devotional life of the Church.

Icons and the eschatological Vision

Icons also reflect the eschatological vision of the Church, pointing toward the ultimate fulfillment of creation in the Kingdom of God. The transfigured figures and radiant colors of icons symbolize the renewal of all things in Christ, offering a foretaste of the heavenly reality. In this sense, icons are not only windows to the divine but also windows to the eschaton (the ultimate end or fulfillment of creation) – the final, redeemed state of creation.

The icon of the Transfiguration, for example, vividly captures this eschatological dimension. It depicts Christ in glory, surrounded by Moses and Elijah, with Peter, James, and John witnessing the event. The icon invites the viewer to contemplate the transfigured state of humanity and creation, made possible through Christ’s redemptive work.

The icon as a universal theological expression

Although deeply rooted in Orthodox Christianity, the theological principles of icons resonate universally. By uniting the earthly and the heavenly, the visible and the invisible, icons articulate a vision of the material world as capable of bearing the divine. This belief, shared across many spiritual traditions, affirms the sacred potential of creation. Icons thus transcend their historical and cultural origins, offering a timeless expression of the Christian mystery.

Examples

Here are some further examples of Orthodox icons from a visit to the the Icon Museum in Frankfurtꜛ in 2024, illustrating the rich theological and artistic tradition of Orthodox iconography.

Iconostasis

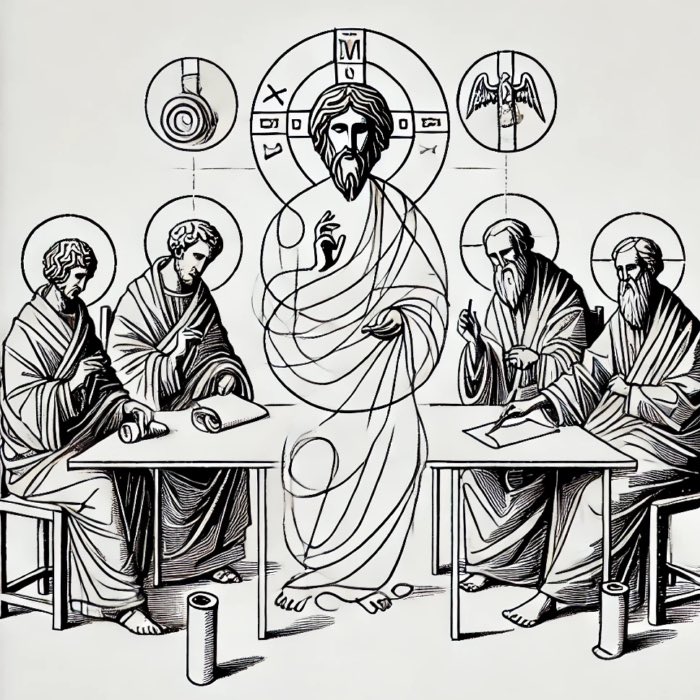

Iconostasis are screens or walls of icons that separate the sanctuary from the nave in Orthodox churches. They serve, like their Catholic counterparts, the rood screen, as a visual barrier between the sacred space of the altar and the congregation, emphasizing the distinction between the earthly and heavenly realms. The iconostasis typically features a central door, known as the Royal Doors, which are opened during key moments of the liturgy, symbolizing the opening of heaven to earth. The icons on the iconostasis depict Christ, the Virgin Mary, and other saints, creating a visual narrative of salvation history and the communion of saints.

Royal doors from an iconostasis, Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Royal doors from an iconostasis, Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Royal doors from an iconostasis (detail), Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Royal doors from an iconostasis (detail), Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Royal doors from an iconostasis (detail), Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Royal doors from an iconostasis (detail), Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Royal doors from an iconostasis (detail), Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Royal doors from an iconostasis (detail), Cyprus, 1754, Wood, carved and gilded, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Arrangement of Icons: Archangel Michael Archistrategos (Voivode) as Apocalyptic Horseman (top, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood), Archangel Michael (left, Russia, 18th/19th century, bronze), Archangel Gabriel (right, Russia, 18th/19th century, bronze), and Saints Florus, Basil, Modestos, Laurus and a Guardian Angel (bottom, Russia, 18th/19th century, egg tempera on wood). Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Arrangement of Icons: Archangel Michael Archistrategos (Voivode) as Apocalyptic Horseman (top, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood), Archangel Michael (left, Russia, 18th/19th century, bronze), Archangel Gabriel (right, Russia, 18th/19th century, bronze), and Saints Florus, Basil, Modestos, Laurus and a Guardian Angel (bottom, Russia, 18th/19th century, egg tempera on wood). Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Deesis

A central theme in Orthodox iconography is the Deesis, a representation of Christ flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist. The Deesis, which means “supplication” or “entreaty” in Greek, is a powerful image of intercession and prayer. Christ, as the Pantocrator (Ruler of All), is depicted in the center, usually holding a book of the Gospels and blessing with his right hand. The Virgin Mary, known as the Theotokos (God-bearer), and John the Baptist, the Forerunner, stand on either side, presenting their petitions to Christ on behalf of humanity. The Deesis is a visual expression of the Church’s belief in the communion of saints and the intercessory role of the Virgin Mary and the saints in the life of the faithful.

Deesis, Mother of God, Christ Pantocrator, John the Baptist Russia, 16th century Egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Deesis, Mother of God, Christ Pantocrator, John the Baptist Russia, 16th century Egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Narrative arrangement of icons. Top: Our Lady of the Sign (Znamenie), Russia, beginning of 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Bottom: Deesis, Mother of God, Christ Pantocrator, John the Baptist, Russia (Moscow), end of 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Narrative arrangement of icons. Top: Our Lady of the Sign (Znamenie), Russia, beginning of 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Bottom: Deesis, Mother of God, Christ Pantocrator, John the Baptist, Russia (Moscow), end of 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Jesus Christ

Christ is a central figure in Orthodox iconography, depicted in various forms and titles that emphasize different aspects of his identity and ministry. The Pantocrator (Ruler of All) icon shows Christ as the divine judge and king, holding a book of the Gospels and blessing with his right hand. The Mandylion icon, based on the legend of King Abgar of Edessa, depicts Christ’s face imprinted on a cloth, symbolizing his divine presence. The Christ Enthroned icon shows Christ seated on a throne, surrounded by angels and saints, emphasizing his role as the eternal king and judge.

Mandylion, ‘Saviour with the wet beard’ type, Russia (Moscow), 16th century Egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mandylion, ‘Saviour with the wet beard’ type, Russia (Moscow), 16th century Egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, Northern Russia, 17th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, Northern Russia, 17th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s entry into Jerusalem (detail), Northern Russia, 17th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s entry into Jerusalem (detail), Northern Russia, 17th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s descent into hell (Anastasis), Demetrios Phoskalis, Greece (Ionian Islands), around 1710, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s descent into hell (Anastasis), Demetrios Phoskalis, Greece (Ionian Islands), around 1710, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s descent into hell (Anastasis) (detail), Demetrios Phoskalis, Greece (Ionian Islands), around 1710, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s descent into hell (Anastasis) (detail), Demetrios Phoskalis, Greece (Ionian Islands), around 1710, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s descent into hell (Anastasis) (detail), Demetrios Phoskalis, Greece (Ionian Islands), around 1710, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Christ’s descent into hell (Anastasis) (detail), Demetrios Phoskalis, Greece (Ionian Islands), around 1710, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

‘Don’t Cry for Me, Mother’, Russia, 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

‘Don’t Cry for Me, Mother’, Russia, 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Lamentation of Christ, Romania (Brasov; Transylvania), 2nd half of 19th century, reverse glass painting. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Lamentation of Christ, Romania (Brasov; Transylvania), 2nd half of 19th century, reverse glass painting. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Resurrection of Christ, Michailo Milyutin, Russia (Moscow), 1685, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Resurrection of Christ, Michailo Milyutin, Russia (Moscow), 1685, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

New Testament Trinity, Russia, 19th century, tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt. The motif of this icon, the depiction of Jesus along with God and the Holy Spirit, is a common theological representation, visually expressing the doctrine of the Trinity. However, why the God gets obviously depicted in these motifs, while any depiction of him is actually forbidden in the Bible, is a question that should be discussed in a theological context.

New Testament Trinity, Russia, 19th century, tempera on wood, Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt. The motif of this icon, the depiction of Jesus along with God and the Holy Spirit, is a common theological representation, visually expressing the doctrine of the Trinity. However, why the God gets obviously depicted in these motifs, while any depiction of him is actually forbidden in the Bible, is a question that should be discussed in a theological context.

New Testament Trinity (detail), Russia, 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

New Testament Trinity (detail), Russia, 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

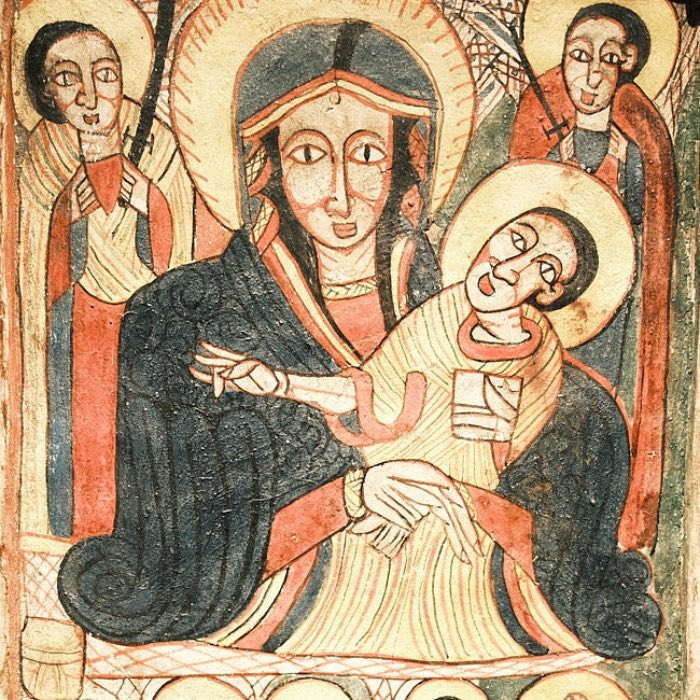

Mother of God

Mary, the Mother of God, also holds a central place in Orthodox iconography. Known as the Theotokos (God-bearer), she is venerated as the one who bore Christ into the world. Mary’s icons depict her in various roles and titles, each emphasizing a different aspect of her relationship with Christ and the Church. The Hodegetria (“She Who Shows the Way”) icon, for example, shows Mary pointing to Christ as the path to salvation. The Vladimirskaya icon, named after the city of Vladimir, depicts Mary tenderly holding the Christ Child. The Kazanskaya icon, from the city of Kazan, emphasizes Mary’s role as the protector of Russia. These icons, and many others, highlight Mary’s unique place in salvation history and her intercessory role in the life of the faithful.

Mother of God (Vladimirskaya), Russia, around 1750, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God (Vladimirskaya), Russia, around 1750, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God unexpected joy, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God unexpected joy, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God unexpected joy (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God unexpected joy (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God Life-Giving Source, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God Life-Giving Source, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God of Kazan (Kazanskaya), Russia, after 1800, egg tempera on wood, gilded oklad, with coloured stones. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God of Kazan (Kazanskaya), Russia, after 1800, egg tempera on wood, gilded oklad, with coloured stones. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Fiery Mother of God (Ognevidnaya), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, egg tempera on wood, oklad: metal, velvet, fresh water pearls, glass stones and rhinestones. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The Fiery Mother of God (Ognevidnaya), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, egg tempera on wood, oklad: metal, velvet, fresh water pearls, glass stones and rhinestones. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Dormition of the Mother of God, Russia, 19th century, Brass, enamelled, four colours. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Dormition of the Mother of God, Russia, 19th century, Brass, enamelled, four colours. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Madre della Consolazione (Our Lady of Consolation), Italian-Cretan, around 1500, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Madre della Consolazione (Our Lady of Consolation), Italian-Cretan, around 1500, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Pre-Annunciation at the Well, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Pre-Annunciation at the Well, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Birth of Mary, Mother of God, Russia, late 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Birth of Mary, Mother of God, Russia, late 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Birth of Mary, Mother of God (detail), Russia, late 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Birth of Mary, Mother of God (detail), Russia, late 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

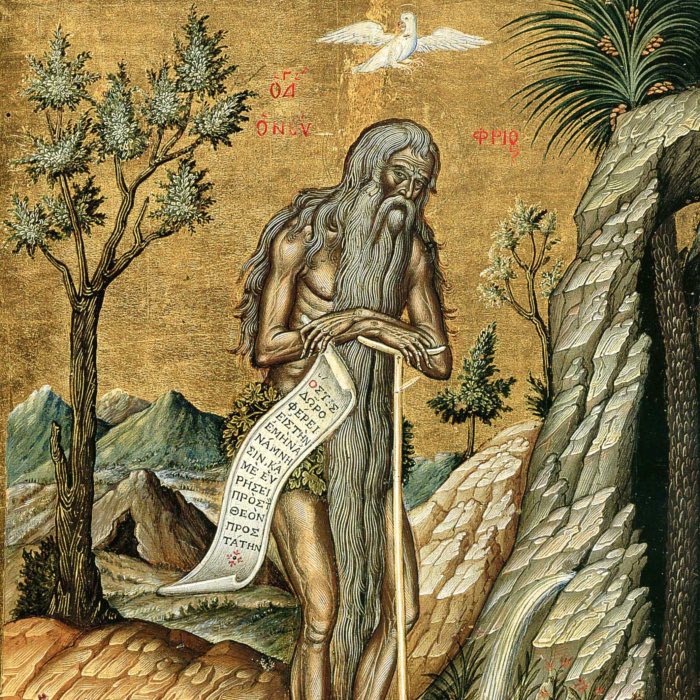

Saints

St. Christophoros, Crete, 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Christophoros, Crete, 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Christophoros (detail), Crete, 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Christophoros (detail), Crete, 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Christophoros Kynokephalos, the Dog-Headed, Russia, around 1850, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Christophoros Kynokephalos, the Dog-Headed, Russia, around 1850, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Christophoros Kynokephalos, the Dog-Headed, Russia, around 1850, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Christophoros Kynokephalos, the Dog-Headed, Russia, around 1850, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. John the Evangelist and St. Basil the Fool, Russia, end of 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. John the Evangelist and St. Basil the Fool, Russia, end of 16th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Catherine of Alexandria, Russia, end of 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Catherine of Alexandria, Russia, end of 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints Kosmas and Damian, Russia, around 1850, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints Kosmas and Damian, Russia, around 1850, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Communion of Saints with Guardian Angel, Russia, late 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Communion of Saints with Guardian Angel, Russia, late 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God, Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God, Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God (detail), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God (detail), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God (detail), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God (detail), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God (detail), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Calendar Icon for the entire year with depictions of the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God (detail), Russia, 2nd half of 19th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints George, Clemens and Menas, Russia (Novgorod), 15th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints George, Clemens and Menas, Russia (Novgorod), 15th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints George, Clemens and Menas (detail), Russia (Novgorod), 15th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints George, Clemens and Menas (detail), Russia (Novgorod), 15th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints Boris and Gleb, Russia, 18th century, Bronze, enamelled, two colours. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Saints Boris and Gleb, Russia, 18th century, Bronze, enamelled, two colours. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicholas, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicholas, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Alexander Nevsky, Russia, around 1850, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Alexander Nevsky, Russia, around 1850, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Two saint (unknown details). Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Two saint (unknown details). Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Two saint (unknown details). Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Two saint (unknown details). Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Two Figures of St. Nil Stolbenski as Pillar-Saint, Russia, 19th century, wood, carved. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Two Figures of St. Nil Stolbenski as Pillar-Saint, Russia, 19th century, wood, carved. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita icons

Vita icons are a special type of icon that tells the life story of a saint. They are usually painted in a series of scenes, each depicting a significant event in the saint’s life. The scenes are arranged in chronological order, starting with the saint’s birth and ending with their death or martyrdom.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl, Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl, Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

St. Nicetas of Pereyaslavl (detail), Vita icon, Russia, 18th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of St. Pantaleon, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of St. Pantaleon, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of St. Pantaleon (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of St. Pantaleon (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of John the Baptist, Russia (Palekh), 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of John the Baptist, Russia (Palekh), 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of John the Baptist, Russia (Palekh), 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Vita Icon of John the Baptist, Russia (Palekh), 18th century, tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mystical themes

Mother of God with Sun and Moon, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. This icon is an example of how the medium is used to express mystical themes. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God with Sun and Moon, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. This icon is an example of how the medium is used to express mystical themes. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God with Sun and Moon (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. This icon is an example of how the medium is used to express mystical themes. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God with Sun and Moon (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. This icon is an example of how the medium is used to express mystical themes. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God with Sun and Moon (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. This icon is an example of how the medium is used to express mystical themes. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Mother of God with Sun and Moon (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. This icon is an example of how the medium is used to express mystical themes. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Sophia, the Divine Wisdom, Russia, around 1800, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Sophia, the Divine Wisdom, Russia, around 1800, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Sophia, the Divine Wisdom (detail), Russia, around 1800, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Sophia, the Divine Wisdom (detail), Russia, around 1800, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

The all-seeing eye of God (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Ikonenmuseum Frankfurt.

Conclusion

The the Orthodox Church, icons are far more than artistic creations; they are profound expressions of faith that bridge the material and the spiritual, the historical and the eternal. They embody centuries of theological reflection, cultural evolution, and artistic mastery. Their role as “windows to heaven” provides believers with a tangible connection to the divine, reinforcing their significance in Orthodox worship and personal devotion.

From their origins in the artistic traditions of late antiquity to their flourishing in the Byzantine Empire and beyond, icons have remained central to the life of the Orthodox Church. Their rich history reflects a continuous dialogue between theology, culture, and art, adapting to new contexts while preserving their essential spiritual purpose. The distinct characteristics of iconography – its symbolic style, theological depth, and liturgical integration – make it a unique and enduring aspect of Christian tradition.

In the modern era, icons continue to inspire and guide the faithful, bridging the gap between the temporal and the eternal. As I experienced firsthand during my visit to the Icon Museum in Frankfurtꜛ, these sacred images invite us into a space where history, theology, and spirituality converge. Whether in grand cathedrals, intimate prayer corners, or public processions, icons remain a living tradition, allowing for a highly personal interpretation of the mysteries and meanings they represent.

References and further reading

- Cornelia A. Tsakiridou, Icons in time, persons in eternity – Orthodox theology and the aesthetics of the Christian image, 2020, Routledge, ISBN: 9780367601768

- Klaus-Rainer Althaus, Snejanka Bauer, Karin Kirchhainer, Guntram Koch, Alexandra Neubauer, Richard Zacharuk, Icons: Icon Museum Frankfurt a.M., 2005, Legat Verlag, ISBN: 9783932942198

- Gennady V. Popov, Natalia Chugreeva, Farben der Heiligkeit – Meisterwerke der Ikonenkunst aus dem Andrej-Rubljow-Museum in Moskau, 2013, Druckerei Wirth

- Alexandra Neubauer, .von der Hand Deines Dieners. Christliche Ikonen der arabischen Welt, 2004, Legat Verlag, ISBN: 9783932942198

- Thomas Böhm, Peter Bruns, Wolfram Drews, Michael Durst, Michael Fiedrowicz, Johannes Franzkowiak, Reinhard Meßner, Eckhard Wirbelauer, Gerhard Philipp Wolf, Die Geschichte des Christentums – Der lateinische Westen und der byzantinische Osten (431-642), 2005, Herder, Ungekürzte Sonderausgabe, Hrsg.: Norbert Brox, Jean-Marie Mayeur, Charles Piétri, ISBN: 9783451291005

- Manolis Chatzidakis, Naxos. Byzantine Art in Greece, 1989, MELISSA Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9602040461

- Arne Effenberger, Hans-Georg Severin, Das Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst, 1992, Herausgeber: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, ISBN: 9783805311854

- Volbach, Wolfgang Fritz, and Lafontaine-Dosogne, Jacqueline, Byzanz und der christliche Osten, 1990, Serie: Propyläen Kunstgeschichte, Propyläen Verlag, Frankfurt am Main

- Denis Walter, Michael Psellos: Christliche Philosophie in Byzanz - Mittelalterliche Philosophie im Verhältnis zu Antike und Spätantike, 2017, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, ISBN: 9783110526028

- Irmgard Hutter, Frühchristliche und byzantinische Kunst - Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, 1991, München: Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, ISBN: 9783763018741

- Georgi Kapriev, Philosophie in Byzanz, 2005, Königshausen & Neumann, ISBN: 9783826026676

- Wladimir Sas-Zaloziecky, Die byzantinische Kunst, 1963, Serie: Ullstein Kunstgeschichte, Verlag Ullstein

- Benjamin Fourlas, Wege nach Byzanz, 2011, Verlag Leibniz-Zentrum für Archäologie (LEIZA), ISBN: 9783884671863

- Arne Effenberger, Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger, Byzanz - Kunst und Kultur, 2017, C.H.Beck, ISBN: 978-3406587023

- Peter Schreiner, Byzanz 565-1453, 2011, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, ISBN: 9783486702712

- André Grabar, Byzanz - die byzantinische Kunst des Mittelalters (vom 8. bis zum 15. Jahrhundert), 1976, Holle, ISBN: 9783873551251

- Wikipedia article on iconsꜛ

- Website of the Icon Museum Frankfurtꜛ

comments