The historical oppression of women in Christianity

The oppression of women in Christian history has roots that intertwine with theological interpretations, ecclesiastical structures, and the cultural contexts in which Christianity developed. While Christianity emerged in a patriarchal society, its teachings and institutions have historically codified and perpetuated gender inequality. In this post, we briefly explore the origins of this oppression.

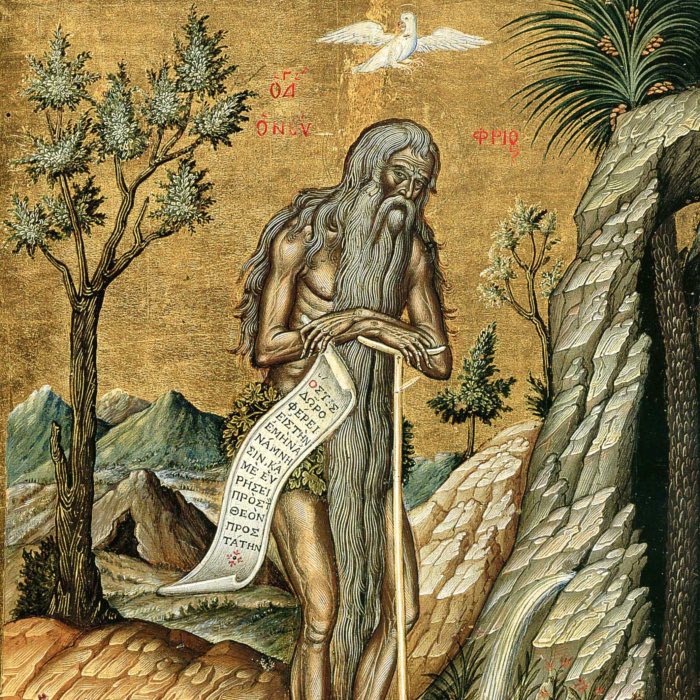

Adam and Eve, workshop of Giovanni della Robbia, 1515.

The snake in this piece has a woman’s face that resembles Eve’s. During the period of this sculpture, women were often described as untrustworthy, and this negative idea is reflected in the gender of the face of the snake. The inscription on the base indicates that this is one of the many works of art made in Florence to celebrate the triumphal entrance of Pope Leo X, a member of Florence’s Medici family, into the city on November 30, 1515. Motifs like these were therefore not rare monuments, but were widespread in the ecclesiastical regime and upheld the idea of Eve, who stood for the entire female sex, as the symbol of “original sin” and thus of evil, theologically justifying the subordination of women. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The role of women in antiquity

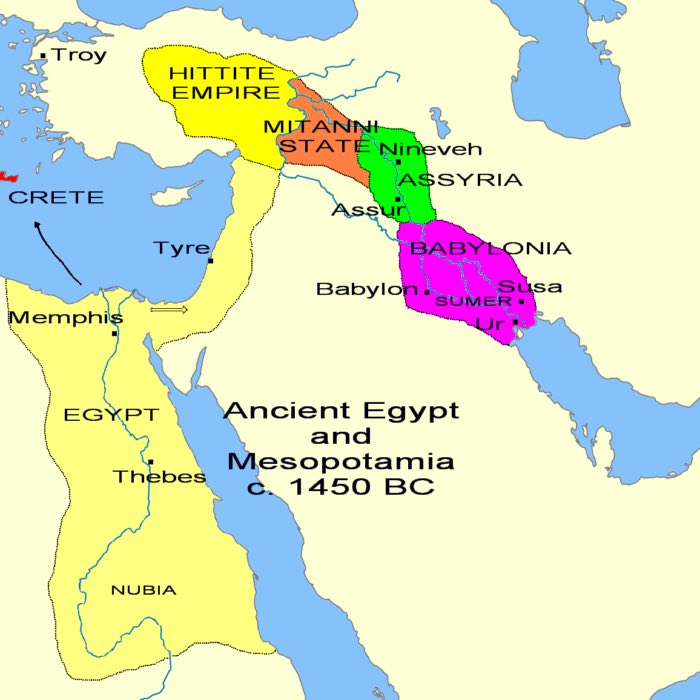

In the ancient world, women’s roles were largely shaped by the patriarchal structures of their societies. In Mesopotamia, one of the cradles of early civilization, women had certain rights, such as owning property and participating in commerce, but they were still subordinate to men, particularly within the family structure. Similarly, in ancient Egypt, women were often depicted as partners in household management and enjoyed legal rights, including the ability to divorce and inherit property. However, their public roles remained limited.

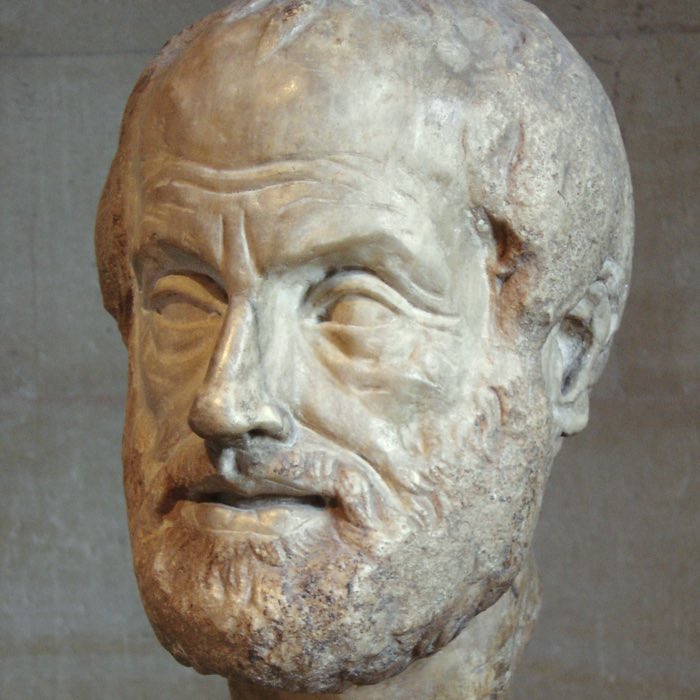

The Greco-Roman world, particularly influential for early Christianity, institutionalized patriarchal norms. In Athens, women were largely confined to domestic roles and excluded from political life, though exceptions existed, such as priestesses in religious cults. Influential thinkers like Aristotle regarded women as biologically and intellectually inferior to men, a view that deeply influenced subsequent Christian thought.

Roman society offered women slightly more freedom. The Roman legal codes allowed them to manage property and influence family affairs, yet they remained excluded from public leadership roles. These cultural norms significantly shaped early Christian views on gender roles.

In Jewish society, gender roles were strictly delineated, with women often relegated to the domestic sphere. Although some Jewish texts, such as Proverbs 31, celebrate women’s virtues, the broader religious framework positioned them as subordinate to men. Women were excluded from many religious practices, including Temple worship and formal education in Torah law.

The role of scripture in justifying women’s subordination

The Christian Bible, particularly the New Testament, contains passages that have been interpreted as endorsing women’s subordination. These texts were written in a patriarchal context and reflect the social norms of their time. However, the way they were selectively emphasized and interpreted by church authorities played a significant role in justifying systemic oppression.

For instance, passages such as 1 Timothy 2:11-12 (“Let a woman learn in silence with full submission. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent”) and 1 Corinthians 14:34-35 (“Women should be silent in the churches”) have been used to exclude women from leadership roles. These texts, attributed to Paul, became foundational in shaping the theology of gender roles. However, their historical authenticity and intent are debated among scholars. Some argue that these passages reflect local issues in early Christian communities rather than universal mandates.

In contrast, other parts of the New Testament, such as Galatians 3:28 (“There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus”), emphasize equality. The selective emphasis on hierarchical texts over egalitarian ones underscores the role of interpretation in shaping Christian attitudes toward women.

Church fathers and the codification of patriarchy

The early Church Fathers played a pivotal role in solidifying patriarchal norms within Christianity. Their theological writings often reflected and reinforced the gender biases of their time. Tertullian (c. 155-240 CE), for example, famously referred to women as “the devil’s gateway”, holding them responsible for humanity’s fall through Eve. By blaming Eve for original sin, Tertullian and other Church Fathers cast women as inherently more susceptible to moral and spiritual failings, reinforcing their exclusion from positions of authority and shaping centuries of doctrinal and societal attitudes toward women.

Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE), while offering a more nuanced theological framework, perpetuated the subordination of women by linking their primary roles to reproduction and marriage.He also interpreted the Genesis narrative as emphasizing Eve’s guilt in the Fall, but added a theological dimension by arguing that her creation from Adam’s rib was secondary, reinforcing the idea that women were inherently subordinate to men in both the natural order and the spiritual hierarchy. This interpretation deeply influenced medieval and later Christian thought, cementing gender inequality within ecclesiastical and social structures.

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274 CE), whose theological system profoundly influenced Catholic doctrine, argued that women were “defective and misbegotten” due to their perceived biological inferiority. His instrumentalization of Aristotelian philosophy for legitimating Christian theology enshrined patriarchal views within the intellectual framework of the Church.

These Church Fathers’ writings were not merely personal opinions but became authoritative teachings that shaped ecclesiastical policies and practices. Their interpretations of scripture and their theological arguments were instrumental in codifying the subordination of women as part of Christian orthodoxy.

Ecclesiastical structures and institutional exclusion

From its earliest days, the Christian Church developed hierarchical structures that excluded women from positions of authority. While evidence from the New Testament and early Christian communities suggests that women held significant roles — such as deaconesses, prophets, and leaders of house churches — these roles were systematically diminished as the Church became institutionalized.

By the 4th century, as Christianity transitioned from a persecuted sect to the official religion of the Roman Empire, its organizational structures mirrored those of the Roman state. Male bishops, modeled on Roman administrative officials, consolidated authority, while women’s roles were increasingly restricted. The Council of Laodicea (c. 363 CE) formally prohibited women from presiding over the Eucharist, reflecting a broader trend of marginalization.

The exclusion of women from priesthood and leadership roles was justified through theological arguments. The idea that Jesus’ apostles were all male was used to argue that leadership in the Church should be restricted to men, despite evidence of prominent female figures in early Christianity, such as Mary Magdalene, who was referred to as the “apostle to the apostles”.

Medieval and early modern developments

During the medieval period, the Church’s attitudes toward women were further entrenched by its emphasis on women’s roles as virgins, wives, or widows. Female saints were often celebrated for their chastity or asceticism, reinforcing the idea that women’s spiritual value lay in their sexual purity or renunciation of the world. The veneration of the Virgin Mary, while elevating a female figure, also idealized unattainable standards of purity and submission.

The rise of monasticism offered some women avenues for autonomy and spiritual authority. Abbesses, for instance, wielded significant power within their communities. However, these opportunities were limited to those who chose a life of celibacy and separation from the broader society.

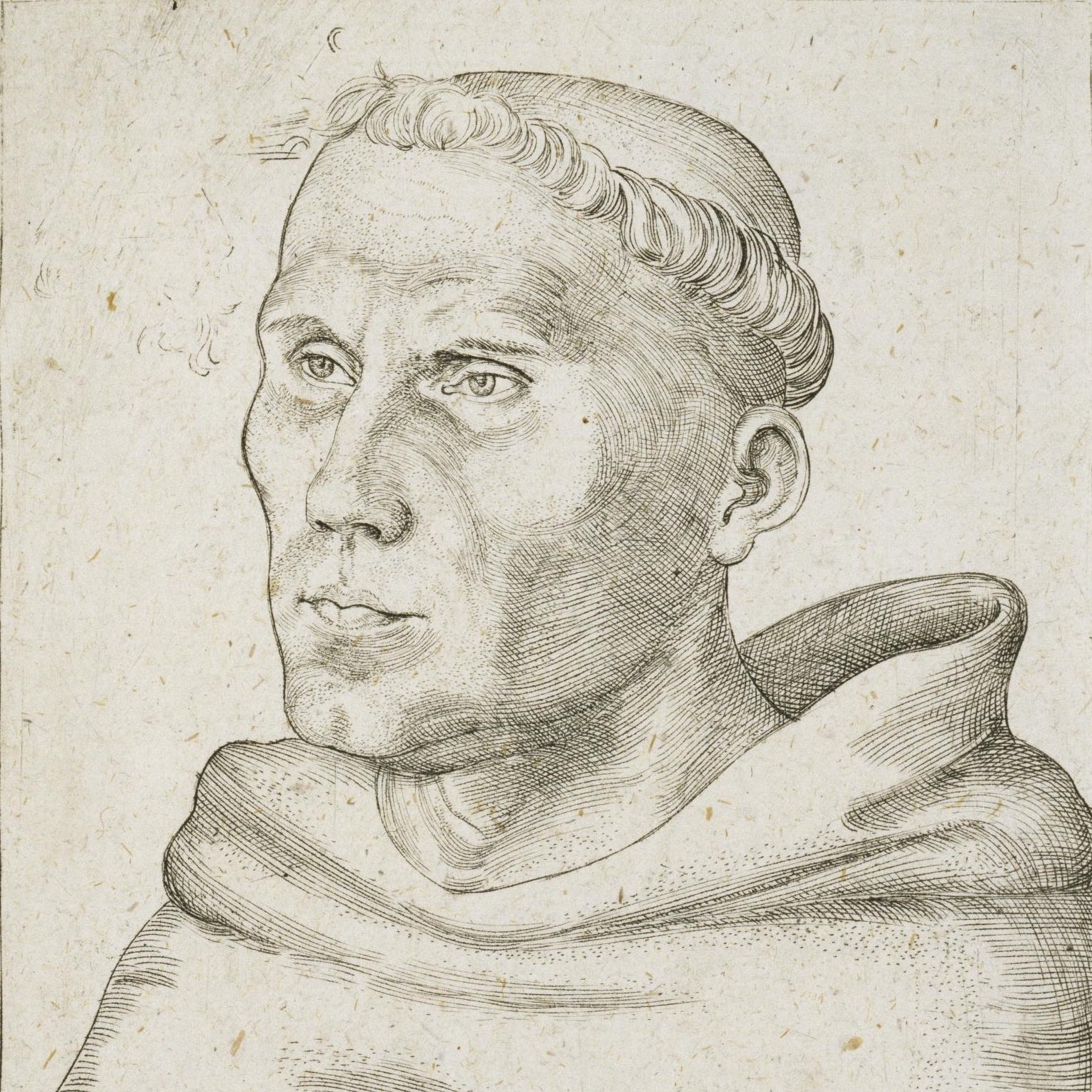

The Reformation of the 16th century brought some changes to women’s roles in Christian practice. Protestant reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin emphasized the importance of marriage and the household, shifting women’s roles toward that of the “Christian wife and mother”. While this granted women a greater sense of dignity within the domestic sphere, it also reinforced their exclusion from public and ecclesiastical leadership.

Modern challenges and reinterpretations

In the modern era, traditional Christian views on women have faced significant challenges from feminist movements, theological reinterpretations, and broader social changes. Feminist theologians, such as Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza and Rosemary Radford Ruether, have critiqued the patriarchal structures of the Church and called for a reexamination of scripture and tradition through a lens of gender equality.

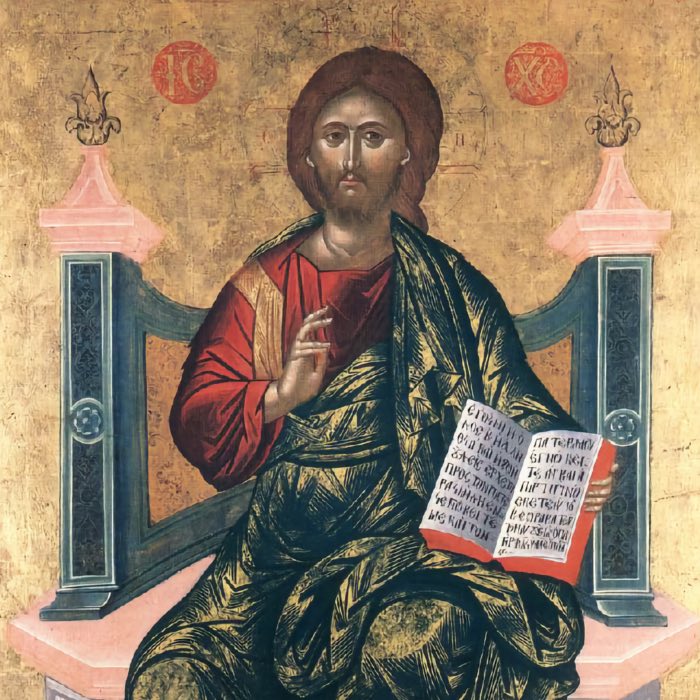

Many contemporary Christian denominations have embraced gender equality, ordaining women as priests, pastors, and bishops. However, significant resistance remains in traditions such as Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, where the exclusion of women from priesthood continues to be justified through appeals to scripture and tradition.

The role of women outside Christianity

The treatment of women in other major world religions provides valuable context for understanding the systemic oppression of women in Christianity. While each religious tradition is unique, many share patriarchal structures that have historically marginalized women.

Judaism

Judaism, as the religious and cultural context from which Christianity emerged, has long exhibited patriarchal tendencies. In traditional Jewish law (Halakha), women were excluded from many religious practices and leadership roles. For example, women could not serve as priests in the Temple, and their testimonies were often deemed inadmissible in legal matters. However, women played vital roles in family and community life, and certain figures, such as Deborah, a prophetess and judge, are celebrated in the Hebrew Bible. Modern movements like Reform and Conservative Judaism have significantly expanded women’s roles, ordaining female rabbis and advocating for gender equality.

Islam

Islam, like Christianity and Judaism, developed within a patriarchal cultural framework. The Quran grants women certain rights, such as the ability to own property and receive an inheritance, which were revolutionary in seventh-century Arabia. However, traditional interpretations of Islamic law (Sharia) often subordinate women, particularly in matters of marriage, divorce, and public roles. Women are frequently excluded from positions of religious authority, though reformist movements and modern interpretations are challenging these norms. Female religious scholars, such as Aisha during the Prophet Muhammad’s time, demonstrate the historical presence of influential women in Islam.

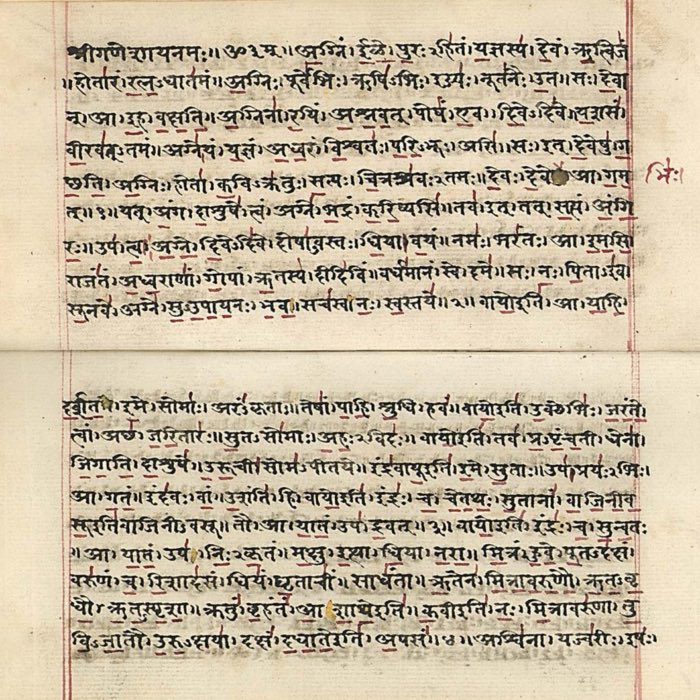

Hinduism

Hinduism’s attitudes toward women are diverse, reflecting its complex and multifaceted nature. While Hindu scriptures include goddesses like Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Durga, who embody wisdom, wealth, and power, societal norms have historically restricted women’s roles. Practices like child marriage and sati (widow immolation) emerged in certain periods, though these were not universally practiced or supported by religious texts. Reform movements in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as those led by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Mahatma Gandhi, have worked to challenge oppressive practices and advocate for women’s rights.

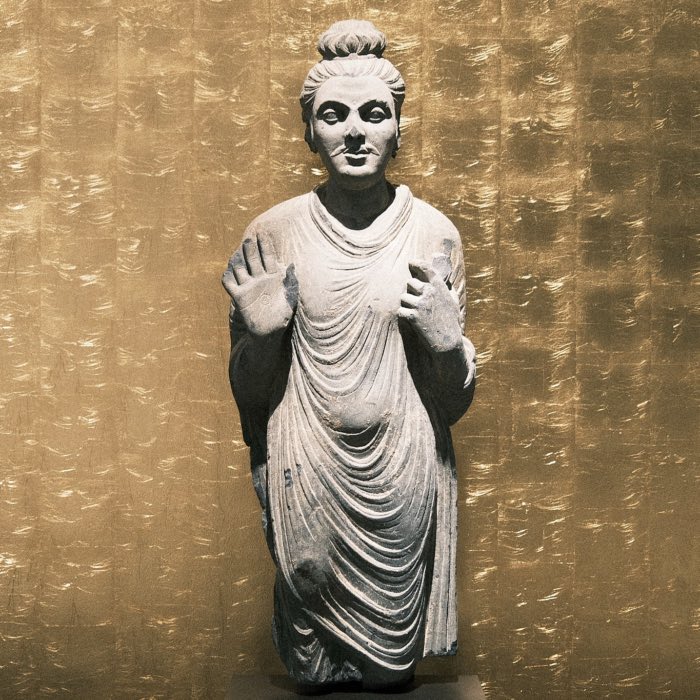

Buddhism

Buddhism presents a more complex picture regarding women’s roles. While the Buddha allowed women to join the monastic community (Sangha) as bhikkhunis, they were placed under stricter rules than their male counterparts. Women’s potential for enlightenment is affirmed in Buddhist teachings, but cultural practices in many Buddhist-majority societies have limited their religious and social roles. Contemporary movements, particularly in the West, have sought to restore gender equality within Buddhist institutions.

Legacy

Christianity’s emergence in a patriarchal society is often cited as a contextual justification for its gendered hierarchies. However, this argument overlooks the fact that early Christian teachings often emphasized radical equality. The narrated interactions of Jesus with women in theNew Testament, including figures like Mary Magdalene, demonstrated a departure from the rigid gender norms of his time, recognizing women as spiritual equals. Early Christian communities included women in leadership roles, such as deaconesses and prophets, suggesting that equality was not only a possibility but a reality within certain early contexts.

Despite these egalitarian roots, the institutional Church, dominated by male leaders, chose to align itself with the patriarchal structures of the surrounding society. This alignment was not accidental but a calculated move to consolidate power and authority. By the 4th century, theological interpretations, such as those emphasizing Eve’s culpability for original sin, were weaponized to justify the exclusion of women from leadership roles and to fortify a male-dominated hierarchy.

The consequences of this theological subordination were devastating and far-reaching. By sanctifying women’s inferiority, the Church legitimized:

- Subjugation in the family: Women were placed under the authority of their husbands, with obedience framed as a divine mandate.

- Lack of political voice: Women were excluded from governance, both within the Church and in broader societal structures.

- Denial of education and intellectual participation: Women were systematically barred from theological education and public intellectual life – unless they decided to live a life in celibacy and seclusion in order to join a convent.

- Sanctioned violence: Theological arguments were used to justify practices such as marital rape and physical abuse, which were framed as the husband’s right.

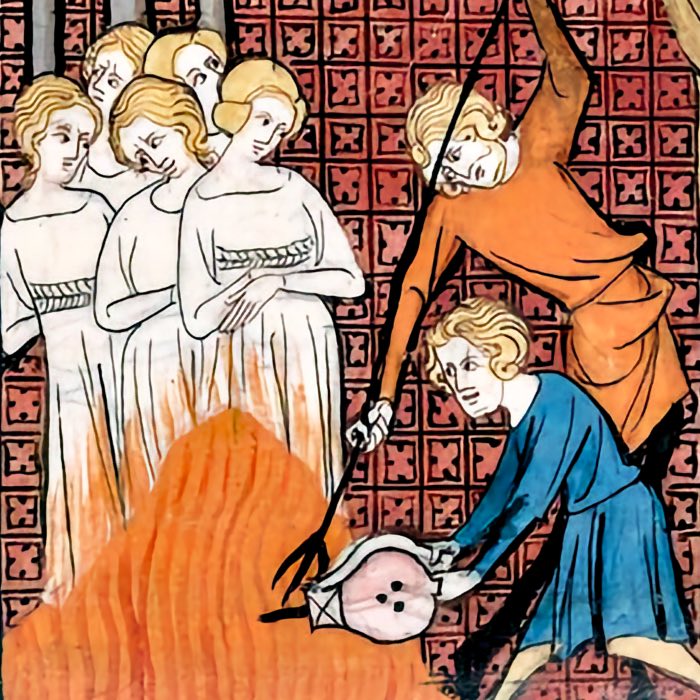

- The witch hunts: During the early modern period, tens of thousands of women were accused of witchcraft and executed, often under the guise of protecting Christian society from female “deviance” or “demonic” influence.

- Sexual exploitation: In some contexts, nuns and other religious women faced abuse within the very institutions that claimed to protect them.

- Economic marginalization: Women’s access to property and economic independence was severely restricted, ensuring dependence on male relatives or institutions.

These atrocities were not inevitable outcomes of Christian teachings but deliberate choices made by Church authorities to uphold and expand their power. By aligning themselves with patriarchal norms and fortifying these structures theologically, the Church entrenched systemic gender inequality in ways that would resonate for centuries.

Conclusion

The oppression of women in Christian history is deeply rooted in the cultural, theological, and institutional contexts of the religion’s development. While early Christianity offered glimpses of gender equality, these were overshadowed by adopted patriarchal and the theological interpretations of male church leaders. Over time, these influences were codified into ecclesiastical structures and practices, creating a legacy of systemic inequality.

The repercussions of this historical subjugation were profound, fostering centuries of marginalization, exploitation, and violence against women within Christian societies over centuries – some of which persist to this day. Understanding the historical roots of this oppression is essential for deciphering long believed myths, break with ecclesiastical dogmas and power, and working towards a reappraisal and reparation for the harm women have suffered in the name of this religion.

References and further reading

- Karlheinz Deschner, Das Kreuz mit der Kirche. Eine Sexualgeschichte des Christentums, 1974, Econ, Düsseldorf 1974; überarbeitete Neuausgabe 1992; Sonderausgabe 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811483-9-8

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Brooten, Bernadette, Women leaders in the ancient synagogue, 1982, Brown Judaic Studies, ISBN: 978-0891306702

- Fiorenza, Elisabeth Schüssler, In memory of her: A feminist theological reconstruction of Christian origins, 1994, PublishDrive, ISBN: 978-0824513573

- Ruether, Rosemary Radford, Sexism and God-talk: Toward a feminist theology, 1993, Beacon Press, ISBN: 978-0807012055

- Clark, Elizabeth A., Women in the early Church, 1984, Michael Glazier, ISBN: 978-0814653326

- Pagels, Elaine, Adam, Eve, and the serpent, 1989, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, ISBN: 978-0451204110

- Brundage, Law, sex, and Christian society in medieval Europe, 1990, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226077840

comments