Christian concept of the Holy War

In the previous post, we discussed how the theological concepts of Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) shaped the development of Christian thought. Among his many contributions, Augustine’s concept of the holy war marks a profound and controversial reinterpretation of Christian ethics. This idea, emerging in the context of political instability and external threats to the Roman Empire, reflects the ability of Christian authorities to adapt their teachings to the demands of their time. However, it also raises questions about the compatibility of such adaptations with the cult’s original pacifist teachings.

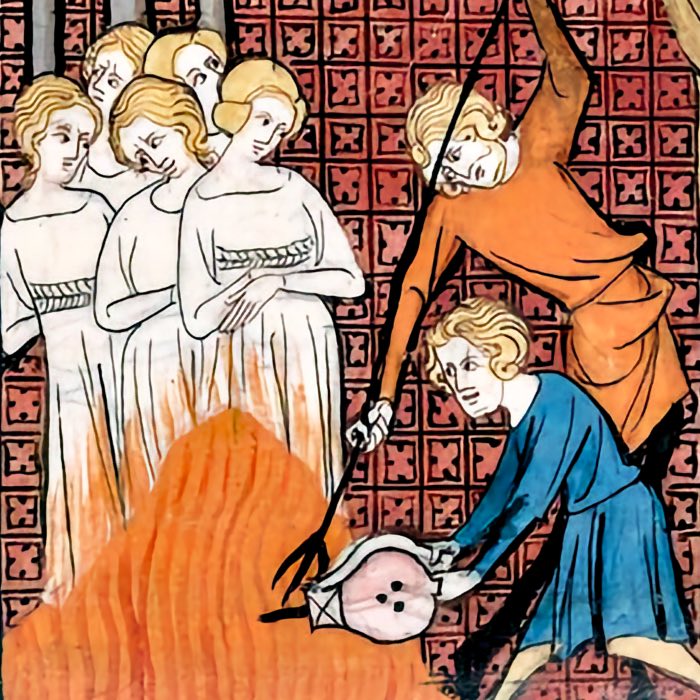

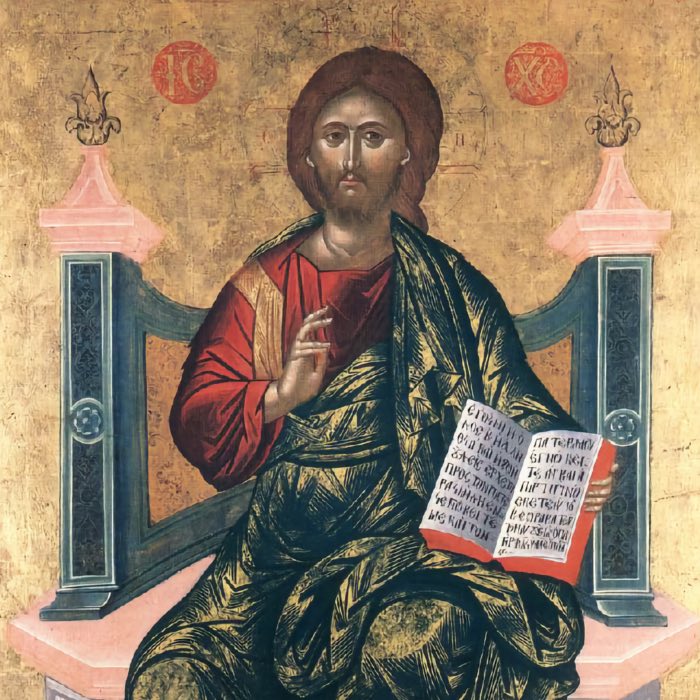

An early example of the miles christianus allegory in a manuscript of the Summa Vitiorum by William Peraldus, mid 13th century. The miles christianus was a Christian allegory of the spiritual warrior, reflecting the fusion of military and religious ideals in medieval Christian thought. The knight depicted is equipped with the Armour of God, including a the Shield of the Trinity, and he is crowned by an angel holding the gloss non coronabuntur nisi qui legitime certaverint (“none will be crowned but those who truly struggle”) and in the other hand a list of the seven beatitudes, matched with the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit and the seven heavenly virtues which in turn are set against the seven cardinal vices. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical context

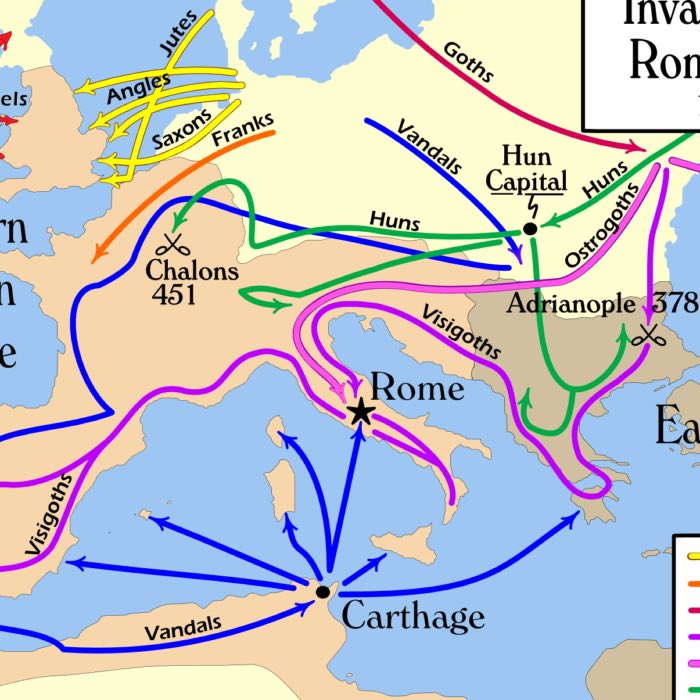

In Augustine’s time, the Roman Empire faced existential threats from so-called “barbarian” invasions, culminating in the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 CE. This crisis, coupled with the empire’s internal instability, created an urgent need for political and military solutions. At the same time, many Christians, adhering to the teachings of Jesus, refused to serve in the Roman army or participate in warfare. Early Christian communities interpreted Jesus’ commands to “turn the other cheek” (Matthew 5:39) and “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44) as clear mandates for non-violence, embodying a commitment to peace even in the face of persecution and societal pressure.

This principled pacifism, however, presented a dilemma for the Roman state, which required soldiers to defend its borders and maintain order. As Christianity became the empire’s dominant religion, Augustine was faced with reconciling the pacifist ideals of the faith with the practical demands of governance and survival.

Augustine’s justification for war

In response to this crisis, Augustine developed a theological framework that justified Christian participation in warfare under certain conditions. This framework, which later became known as the “just war” theory, was articulated primarily in his monumental work, The City of God. According to Augustine, war could be morally permissible — and even necessary — if it met specific criteria:

- A just cause: War must be waged for the right reasons, such as self-defense or the protection of the innocent. It could not be driven by greed, conquest, or personal ambition.

- Legitimate authority: Only a legitimate governing authority could declare war, ensuring that it was not a private act of aggression.

- Right intent: The ultimate goal of war must be the restoration of peace and justice, rather than vengeance or domination.

Augustine’s arguments drew heavily on Roman legal and philosophical traditions, adapting them to a Christian ethical framework. He viewed war as a tragic but sometimes necessary tool to combat evil and maintain order in a fallen world. By framing violence as a means to achieve peace, Augustine reconciled the realities of statecraft with Christian moral ideals.

A departure from Jesus’ teachings

Augustine’s concept of the holy war represents a dramatic departure from the original Christian teachings as understood by early Christians. Jesus’ message emphasized unconditional love, forgiveness, and the rejection of violence. Early Christian martyrs, who chose to suffer rather than fight, embodied this ethic of non-violence. Augustine’s reinterpretation, however, introduced a conditional approach to Christian ethics, allowing for exceptions in the face of practical necessity.

This shift can be seen as a reversal of Jesus’ original message. By constructing a theological justification for violence, Augustine provided a framework that transformed Christianity from a countercultural movement grounded in radical love and peace into a religion capable of sanctioning state-sponsored warfare. The early Christian refusal to fight as soldiers may, in fact, represent a more faithful interpretation of Jesus’ teachings than Augustine’s later accommodation.

Legacy of Augustine’s holy war

Augustine’s just war theory had profound and far-reaching consequences. It laid the intellectual groundwork for later developments, including the medieval Crusades, where the concept of a divinely sanctioned war reached its zenith. Augustine’s framework also normalized the idea that Christianity could align itself with the coercive power of the state, a partnership that would shape Western history for centuries.

More broadly, Augustine’s innovation illustrates Christianity’s capacity for adaptation — or, one might argue, compromise. His theological reinterpretation demonstrates how Christianity was at its beginning not a static or monolithic entity but a dynamic tradition that evolved in response to changing social, political, and cultural circumstances. Rather than adhering rigidly to its original principles, Christianity’s leaders often tailored its teachings to meet the needs of the moment. This adaptability raises questions about the very notion of an “original” Christianity. If the faith’s doctrines are continually reinterpreted and reshaped, can there ever be a fixed or immutable version of Christianity? Maybe it is this very flexibility that has allowed Christianity to endure and thrive over the centuries, adapting to new contexts and challenges while varying the interpretation of its core values.

Conclusion

Augustine of Hippo’s concept of the holy war reflects the dynamic and often contentious evolution of Christian thought. Emerging in a time of crisis, it sought to reconcile the pacifist ethics of early Christianity with the pragmatic demands of a besieged empire. While it provided a theological justification for violence in service of peace, it also marked a significant departure from Jesus’ radical message of love and non-violence.

In my view, this theological innovation highlights the malleability of Christian doctrine and its tendency to adapt to the realities of its historical context. In doing so, Augustine’s “just war” theory not only reshaped Christianity’s ethical landscape but also exemplified the broader pattern of doctrinal evolution within the faith. By crafting a framework that allowed war and violence to coexist with a religion of love and peace, Augustine’s legacy underscores the complexities and contradictions of Christianity’s historical development.

References and further reading

- Brown, P., Augustine of Hippo: A Biography, 2013, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520280410

- Chadwick, H., Augustine: A Very Short Introduction, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192854520

- Markus, R.A., The End of Ancient Christianity, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521339490

- Rist, J.M., Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521589529

- Dodaro, R., Christ and the Just Society in the Thought of Augustine, 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521841627

- Pelikan, J., The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), 1975, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226653716

- Augustine, Confessions, translated by H. Chadwick, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0241295793

- Augustine, The City of God, translated by R.W. Dyson, 1998, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521468435

- Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, translated by D.W. Robertson, 1958, Pearson, ISBN: 978-0024021502

- Augustine, De Trinitate (On the Trinity), translated by O. S. A John E. Rotelle, 2012, New City Press, ISBN: 978-1565484467

- Augustine, On Free Choice of the Will, translated by T. Williams, 1993, Hackett Publishing, ISBN: 978-0872201880

- O’Donnell, J.J., Augustine: A New Biography, 2006, Ecco, ISBN: 978-0060535384

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 4 Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

comments