The concept of hell and its instrumentalization by the Church

The concept of hell occupies a central place in the theological framework of Christianity, functioning as the ultimate consequence of moral failure and estrangement from God. However, the nature and interpretation of hell have undergone significant transformations throughout history. Initially rooted in Jewish and Greco-Roman traditions, the Christian notion of hell evolved into a doctrine deeply entwined with institutional power. By the medieval period, the Church had effectively weaponized the fear of hell to consolidate authority, shape social behavior, and control its adherents. In this post, we trace the evolution of the concept of hell within Christianity, examine its role as a tool of manipulation by the Church, and explore the profound psychological and social consequences it had on believers, particularly in the context of excommunication.

High medieval depiction of hell in the Hortus Deliciarum manuscript of Herrad von Landsberg, around 1180. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Early roots of the Christian concept of hell

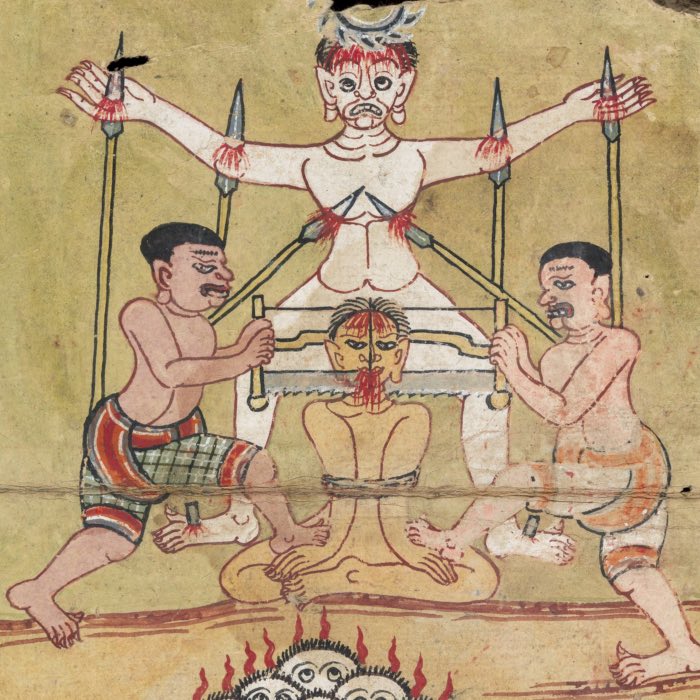

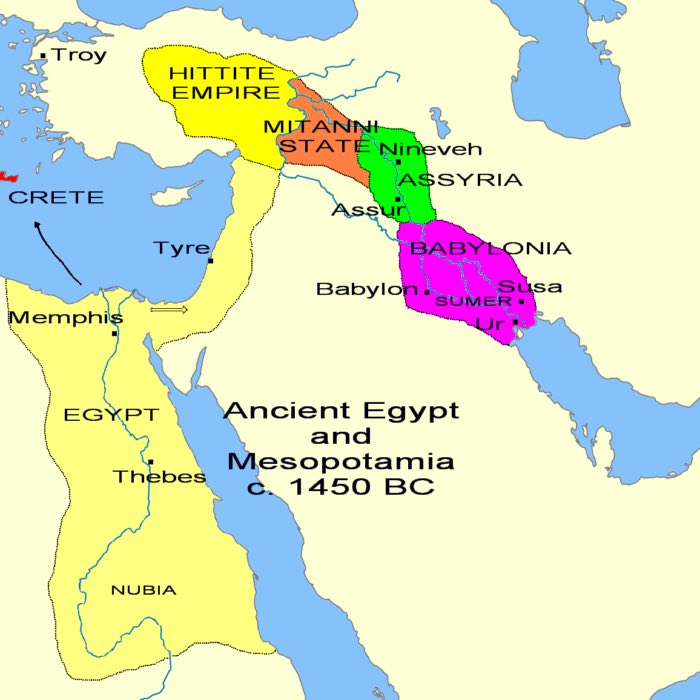

The earliest Christian conceptions of hell were shaped by Jewish apocalyptic literature and the afterlife beliefs of neighboring civilizations, including Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures, as well as Greco-Roman notions of the afterlife.

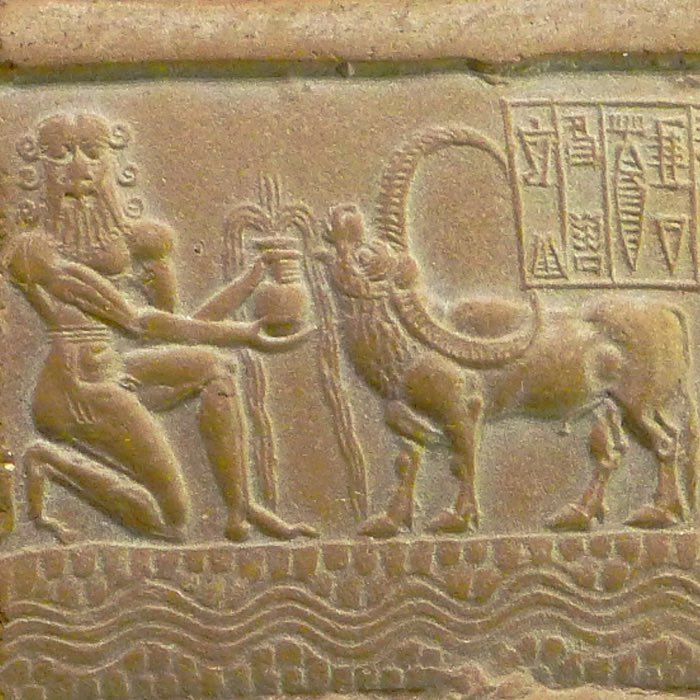

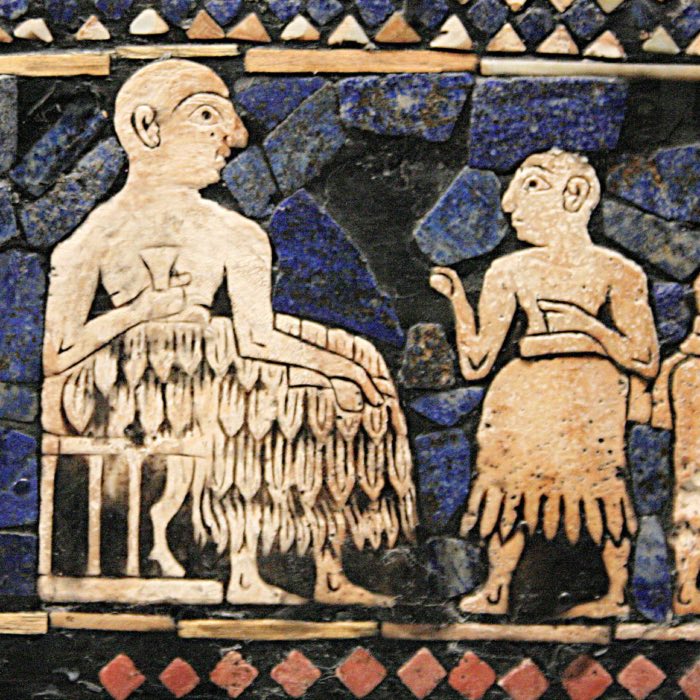

Mesopotamian influence

In Mesopotamian beliefs, the underworld, referred to as Kur or Irkalla, was a shadowy realm where the dead resided in a state of dreary existence. Early Jewish concepts of Sheol bear a striking resemblance, as Sheol was envisioned as a silent, ambiguous place where all the dead go, regardless of moral standing. Over time, as Jewish communities encountered Babylonian religion during the Exile, moral accountability began to influence views of the afterlife, a trend reflected in apocalyptic texts such as the Book of Daniel and 1 Enoch, which introduce ideas of divine judgment and retribution.

Ancient Sumerian cylinder seal impression showing the god Dumuzid being tortured in the Underworld by galla demons, from 2600 until 2300 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

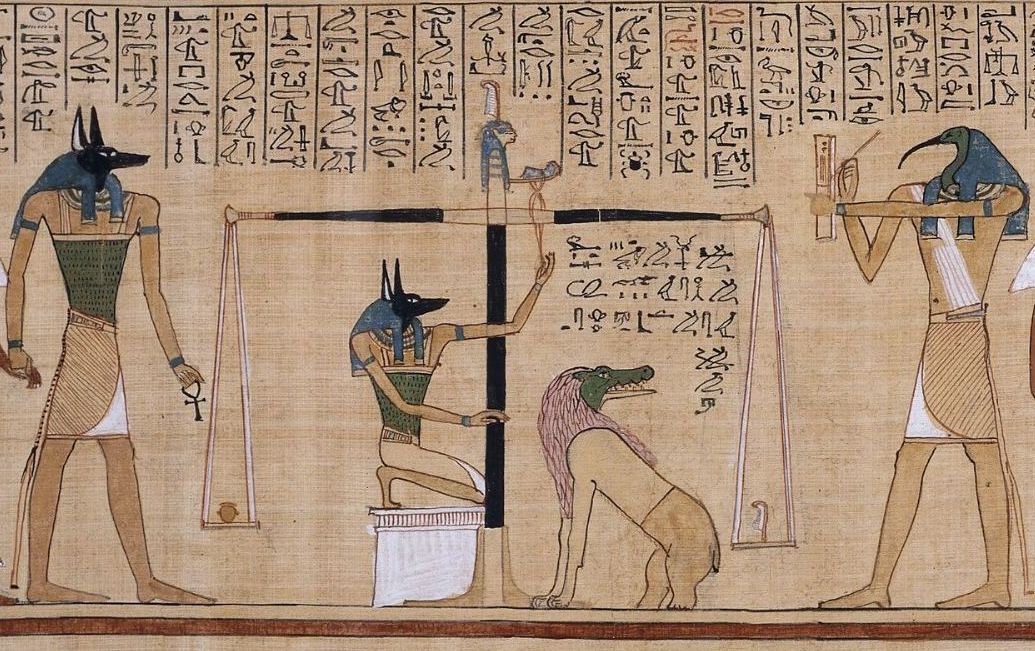

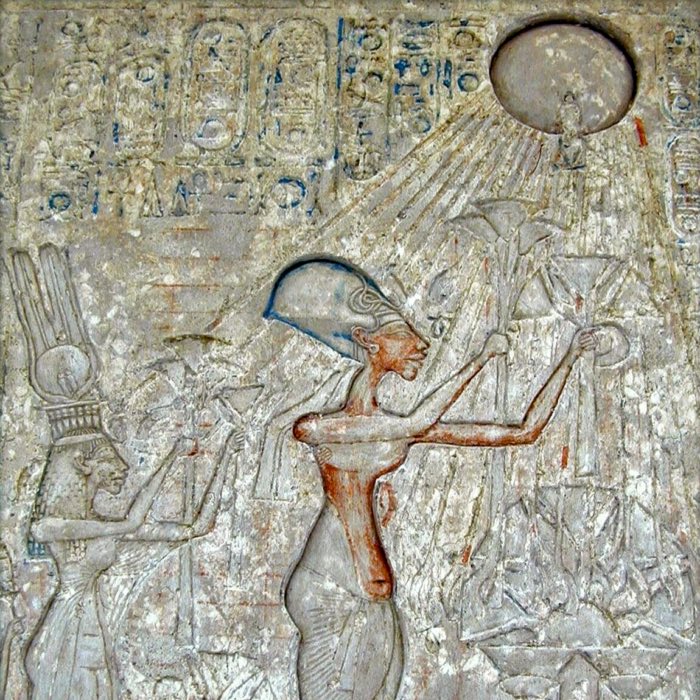

Egyptian influence

Egyptian afterlife beliefs introduced the concept of moral judgment as seen in the “Weighing of the Heart” ceremony from the Book of the Dead. The heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at (truth and justice), with a heavy heart leading to annihilation. This notion of divine judgment for moral failings resonated with Jewish apocalyptic themes and influenced the emerging Christian eschatology. Additionally, the Egyptian concept of fiery punishment for the wicked foreshadows later depictions of Gehenna as a place of torment.

In this ca. 1275 BCE Book of the Dead scene the dead scribe Hunefer’s heart is weighed on the scale of Maat against the feather of truth, by the canine-headed Anubis. The ibis-headed Thoth, scribe of the gods, records the result. If his heart is lighter than the feather, Hunefer is allowed to pass into the afterlife. If not, he is eaten by the crocodile-headed Ammit. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

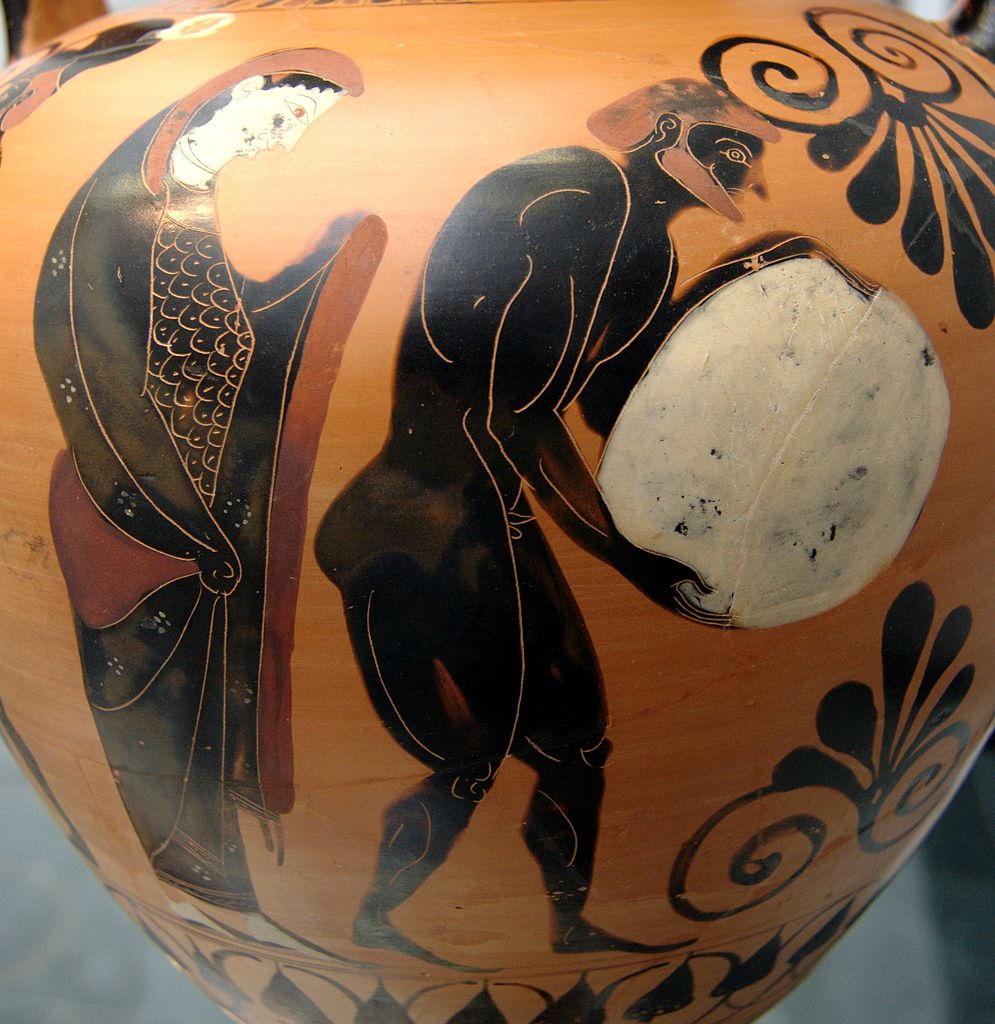

Greco-Roman influence

Greek and Roman ideas, such as Hades and Tartarus, further enriched early Christian notions of hell. These afterlife realms featured structures of reward and punishment, with Tartarus specifically reserved for the wicked. This fusion of Jewish apocalypticism, Egyptian moral judgment, and Greco-Roman mythological imagery laid the foundation for Christian conceptions of hell as a place of divine justice and eternal punishment.

Persephone supervising Sisyphus in the Underworld, Attic black-figure amphora, c. 530 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

New Testament

In the New Testament, references to hell are varied and often ambiguous. Jesus speaks of Gehenna, derived from the Valley of Hinnom, a site associated with idolatry and human sacrifice in ancient Israel. Gehenna is used as a metaphor for divine judgment, emphasizing the seriousness of moral failings. Early Christian interpretations of hell were less detailed than the graphic imagery that later dominated medieval theology.

Valley of Hinnom, 2007. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

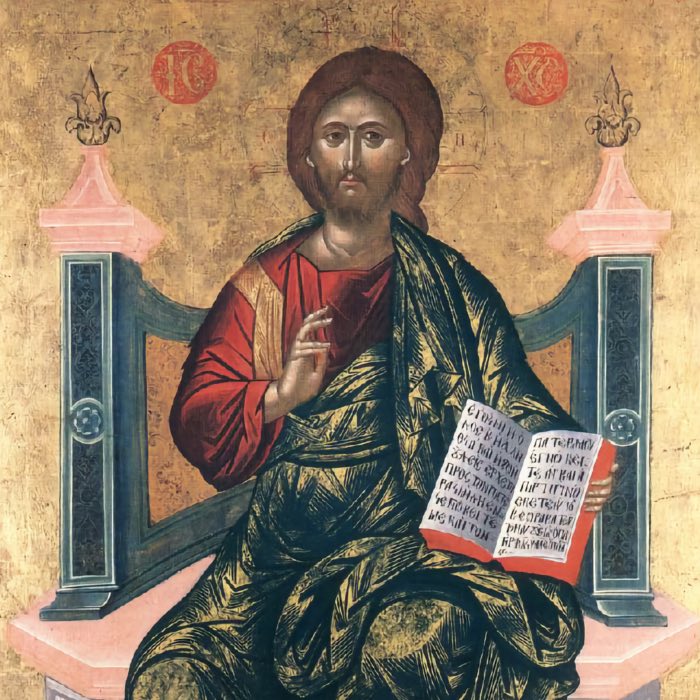

The development of hell in Christian doctrine

The Christian concept of hell became more concrete and terrifying as the Church sought to define orthodoxy and enforce moral discipline. By the late antiquity and early medieval periods, theologians and Church leaders elaborated on the nature of hell, incorporating vivid descriptions of physical and spiritual torment.

Augustine and the eternality of hell

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) played a pivotal role in shaping the doctrine of eternal punishment. In his works, Augustine argued that the suffering of the damned in hell was eternal, reflecting the gravity of sin and the justice of God. He emphasized the dichotomy between salvation through the Church and the eternal fate of those who rejected its teachings. Augustine’s theology laid the groundwork for the institutional Church’s use of hell as a means of moral and doctrinal enforcement.

The medieval expansion of hell’s imagery

During the medieval period, hell took on an increasingly graphic and detailed form, fueled by the theological imagination and artistic representation. Texts like Dante’s Inferno and the Visio Pauli provided elaborate visions of hell’s geography, inhabitants, and punishments. Hell was portrayed as a place of fire, brimstone, and demonic torment, tailored to fit specific sins.

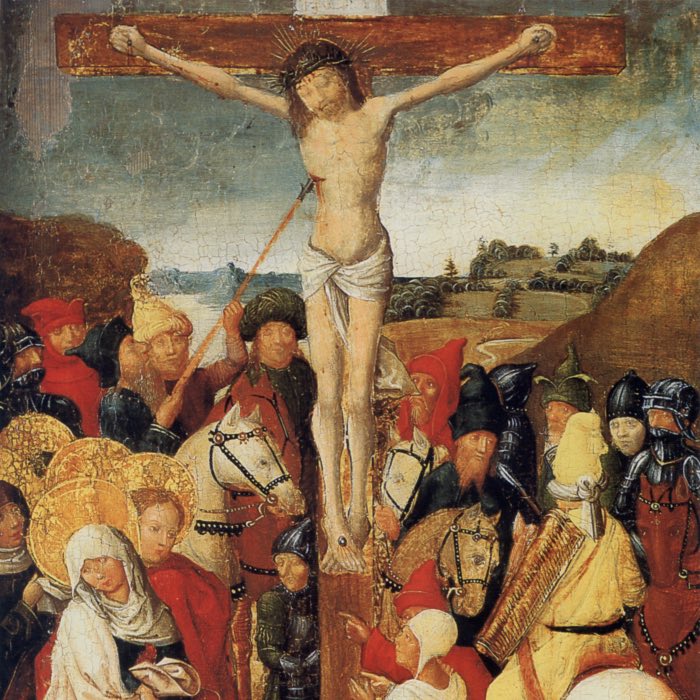

Harrowing of Hell, illuminated manuscript showing Christ leads Adam by the hand, c.1504. Such motifs were prevalent in medieval art, serving to visually convey the concepts of hell and the redemption of souls. These illustrations reinforced Church teachings and underscored its authority, presenting Christ, Christianity’s central figure, as the divine savior. By portraying the act of rescuing souls from hell, the imagery symbolized the Church’s unique role as the sole mediator of salvation on Earth. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

This period also saw the rise of the concept of purgatory, a transitional state of purification for souls not yet worthy of heaven. While distinct from hell, purgatory was often invoked alongside hell to emphasize the consequences of sin and the necessity of Church sacraments.

The instrumentalization of hell by the Church

As the concept of hell became more defined, the Church began to leverage it as a powerful tool of control. The fear of eternal damnation became a cornerstone of ecclesiastical authority, influencing both individual behavior and societal structures.

Hell as a moral regulator

The Church wielded the doctrine of hell to enforce moral discipline and conformity. Preachers used vivid descriptions of hellfire and eternal suffering to instill fear in the faithful, compelling adherence to Church teachings. The Dies Irae, a medieval hymn that graphically describes the Last Judgment, exemplifies the Church’s use of liturgical texts to evoke terror and encourage repentance.

Excommunication and social death

Excommunication, the formal expulsion of a believer from the Church, illustrates the practical consequences of the Church’s hell doctrine. For medieval Christians, who were deeply indoctrinated into the belief that the Church held the keys to salvation, excommunication was tantamount to eternal damnation. The psychological impact of being cast out of the community of the faithful was profound, often equating to social and spiritual annihilation.

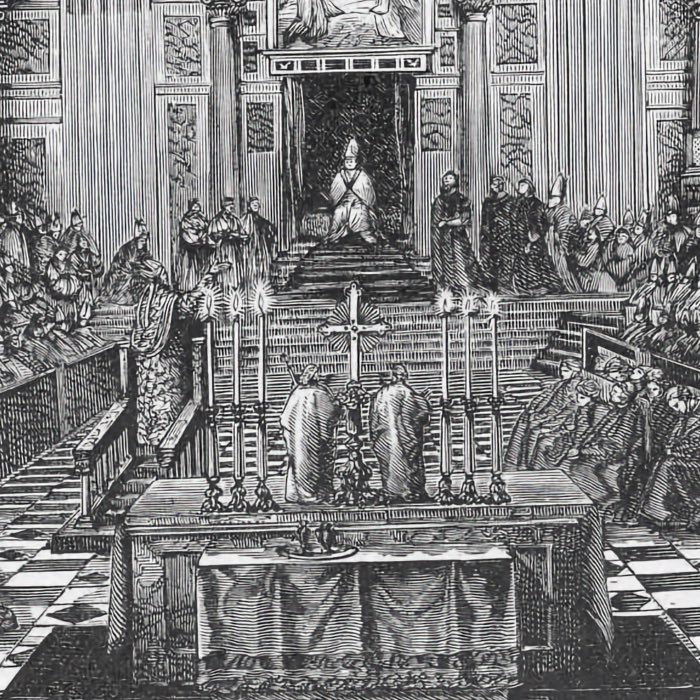

Fanciful 16th-century fresco in the Sala Regia, by Giorgio Vasari, depicting Pope Gregory IX excommunicating Frederick II. Since few details were provided to the artist, Vasari chose to paint an excommunication scene generically. In the traditional excommunication procedure, the pope and his priests would hurl burning candles on the ground and stamp them out. The painter however here chose to show the pope personally stepping on the emperor. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Excommunication also had tangible social consequences. It isolated individuals from their community, cutting them off from sacraments, commerce, and relationships. This duality of spiritual and social death ensured that the Church’s authority remained unchallenged, as few dared to risk the ostracism and fear associated with excommunication.

Political and economic manipulation

The fear of hell extended beyond personal behavior to the realm of politics and economics. The Church used the doctrine of hell to justify crusades, persecutions, and inquisitions, framing dissent and heresy as paths to eternal torment. Indulgences — payments made to reduce time in purgatory — became a lucrative enterprise, exploiting the fear of damnation for financial gain.

The psychological toll of hell doctrine

The Church’s instrumentalization of hell had profound psychological effects on believers. The pervasive fear of eternal punishment fostered a culture of anxiety and guilt, shaping the inner lives of individuals and the collective psyche of communities. This fear often inhibited critical thinking, as questioning Church doctrine was perceived as a mortal risk to one’s soul.

Preserved colonial wall paintings of 1802 depicting Hell, by Tadeo Escalante, inside the Church of San Juan Bautista in Huaro, Peru. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Moreover, the Church’s emphasis on sin and damnation often overshadowed the message of divine love and forgiveness central to Jesus’ teachings. This imbalance created a spiritual climate where fear, rather than faith, became the primary motivator for religious adherence.

Conclusion

The Christian concept of hell has served as both a profound moral framework and a tool of manipulation. While it originated as a means of emphasizing divine justice and accountability, its evolution into a vivid and terrifying doctrine reflects the Church’s desire to consolidate power and control over its adherents. The fear of hell, especially when tied to practices like excommunication, allowed the Church to wield immense influence over both spiritual and temporal realms.

References and further reading

- Le Goff, J., The birth of purgatory, 1986, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226470832

- Russell, J. B., A history of heaven: the singing silence, 1998, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691006840

- McDannell, C., & Lang, B., Heaven: a history, 1988, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300043464

- Moore, R. I., The formation of a persecuting society: power and deviance in western Europe, 950–1250, 2006, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405129640

- Bernstein, A. E., The formation of hell: death and retribution in the ancient and early Christian worlds, 1993, Cornell University Press, ISBN: 978-0801428937

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 4 Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

comments