Dogma and its role in Christian orthodoxy

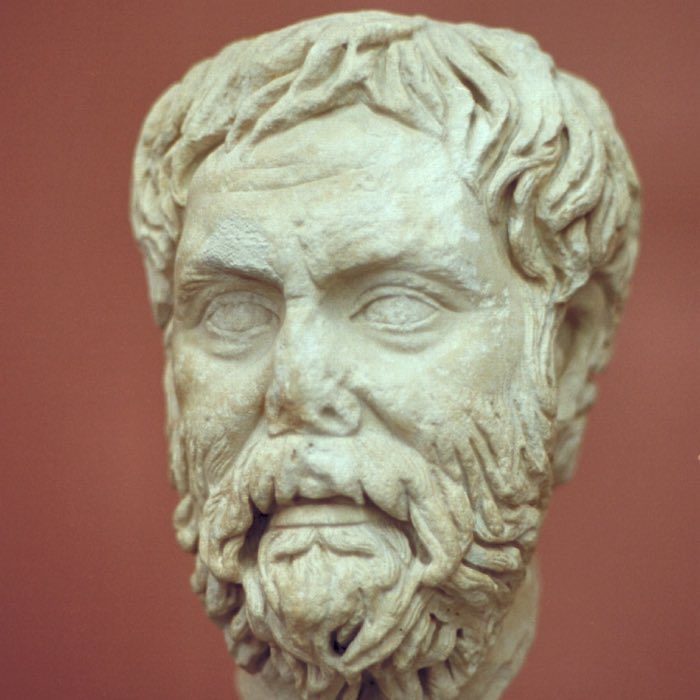

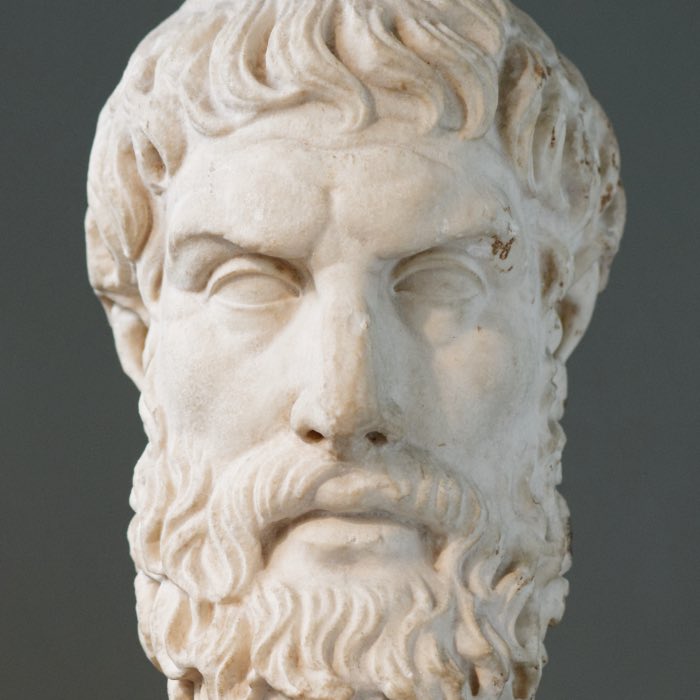

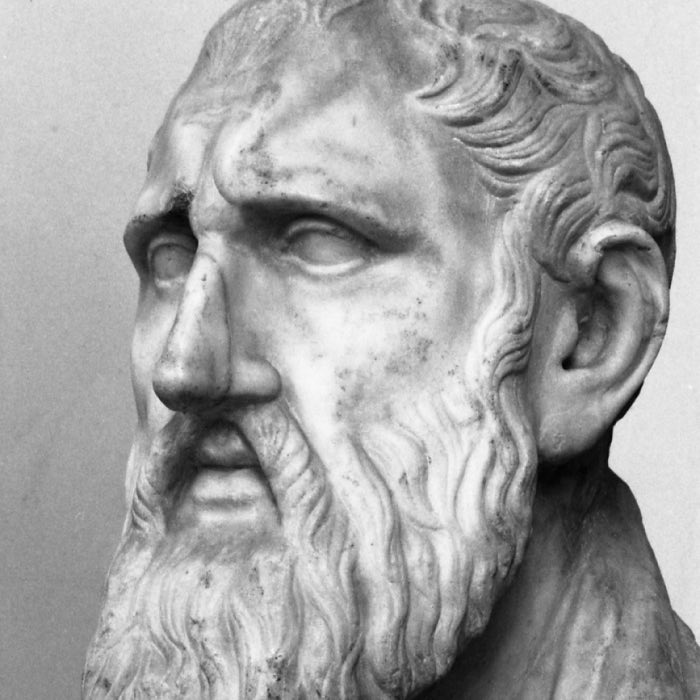

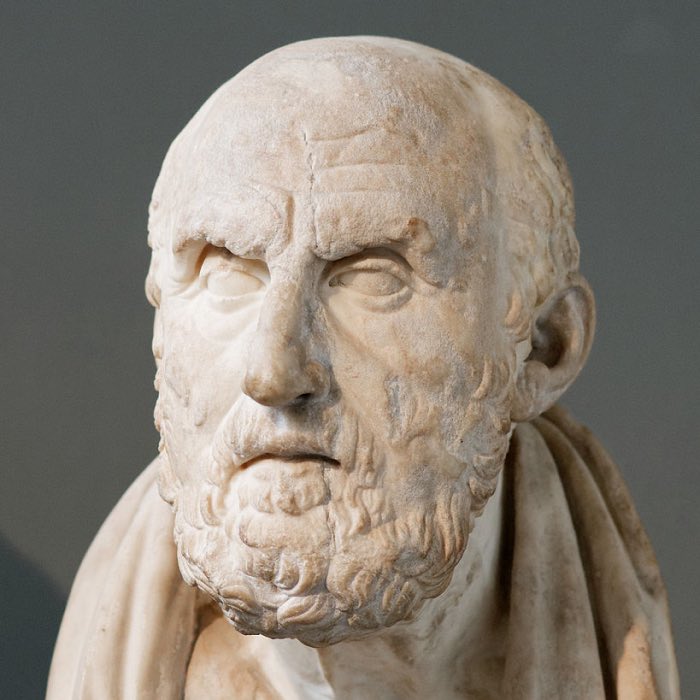

The term “dogma” originates from the Hellenistic philosophical tradition, where it denoted a central tenet or principle held to be authoritative within a given school of thought, such as Stoicism or Epicureanism. In these contexts, dogma referred to reasoned conclusions about nature, ethics, or metaphysics, rooted in dialogue and philosophical inquiry. However, as Christianity adopted and adapted the term, it evolved into a rigid tool of religious authority.

The first Vatican Council, held in Saint Peter’s Basilica during the papacy of Pius IX in 1869. From a book on Pope Pius IX, 1873. Councils like this one were instrumental in defining and enforcing orthodox dogma within the Catholic Church. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Catholic Church’s eventual consolidation of dogma became a means of asserting control over doctrine and community, often with profound and destructive consequences. From the early ecumenical councils to the Middle Ages and beyond, dogma was transformed into a weapon for enforcing orthodoxy and justifying persecution. In this post, we take a closer look at the transition of dogma from its Hellenistic origins to its use in the Catholic Church, focusing on its role in shaping Christian orthodoxy and its impact on religious practice and social dynamics.

Dogma in Hellenistic thought: A foundation of inquiry

In Hellenistic philosophy, dogma was not inherently rigid or oppressive. It represented the essential teachings or positions of a philosophical school, developed through reason, debate, and observation. For example, Stoicism emphasized dogmas about living in harmony with nature, rationality, and the inevitability of fate (see, e.g., oikeiosis). These dogmas were practical guidelines for ethical living. Epicureanism upheld dogmas about the nature of pleasure, the gods’ detachment from human affairs, and the pursuit of ataraxia (tranquility). Crucially, dogma in this context was not imposed by an external authority but embraced through personal conviction and rational agreement. While dogma served as a unifying principle for these schools, it was always open to critique and refinement within the intellectual framework of the time.

The transformation of dogma in early Christianity

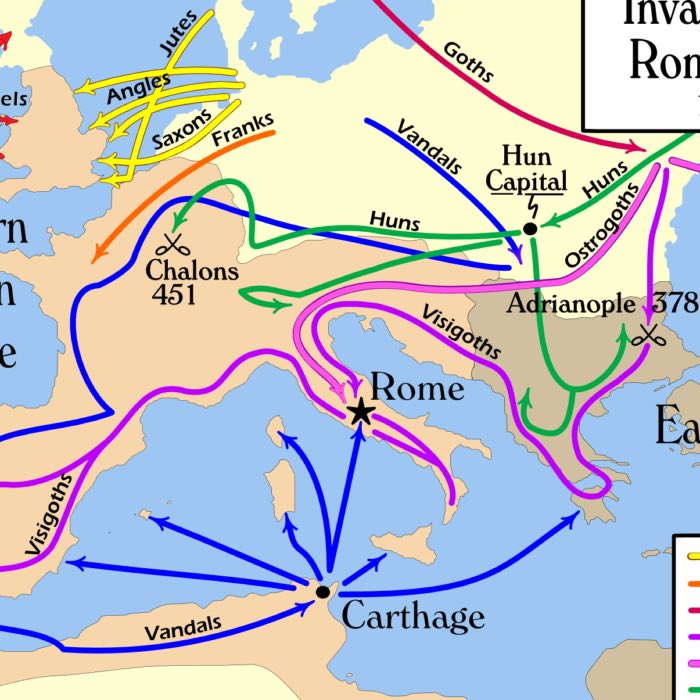

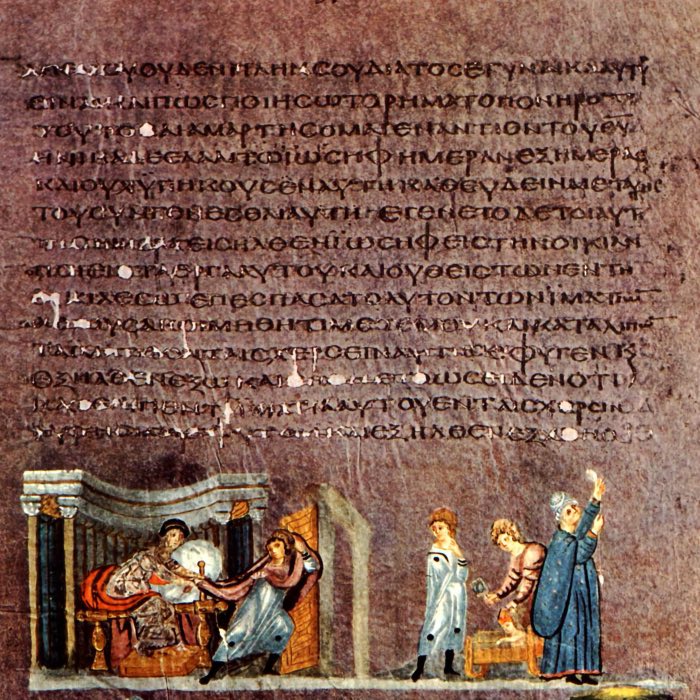

As Christianity emerged and spread throughout the Roman Empire, it began to integrate aspects of Hellenistic philosophy into its theological framework. The adoption of the concept of dogma marked a significant shift from philosophical inquiry to authoritative decree.

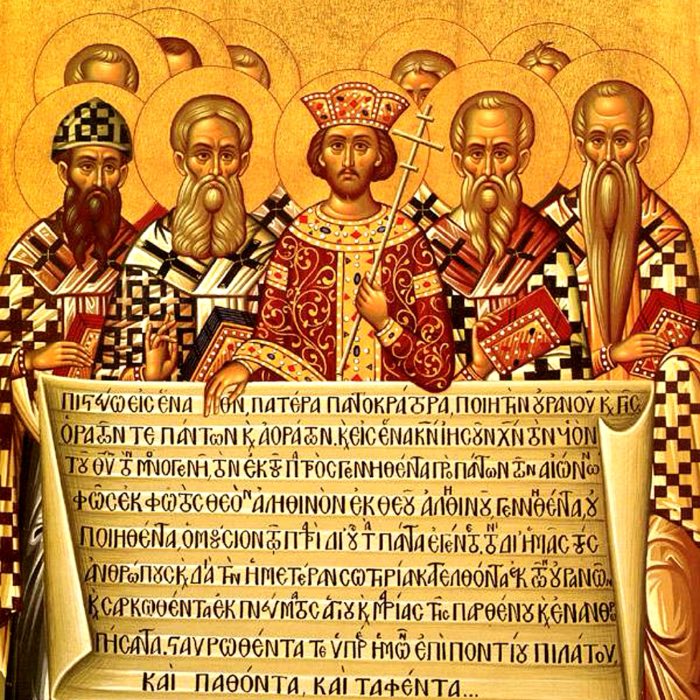

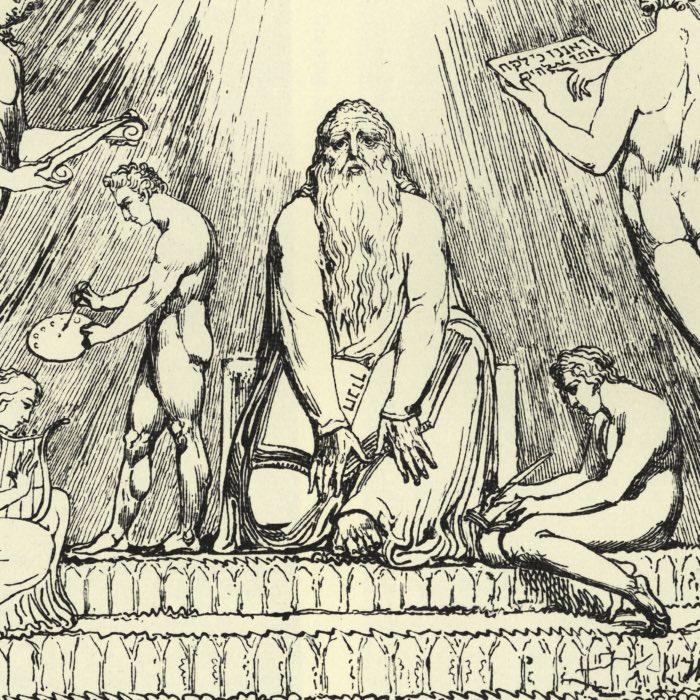

The role of ecumenical councils

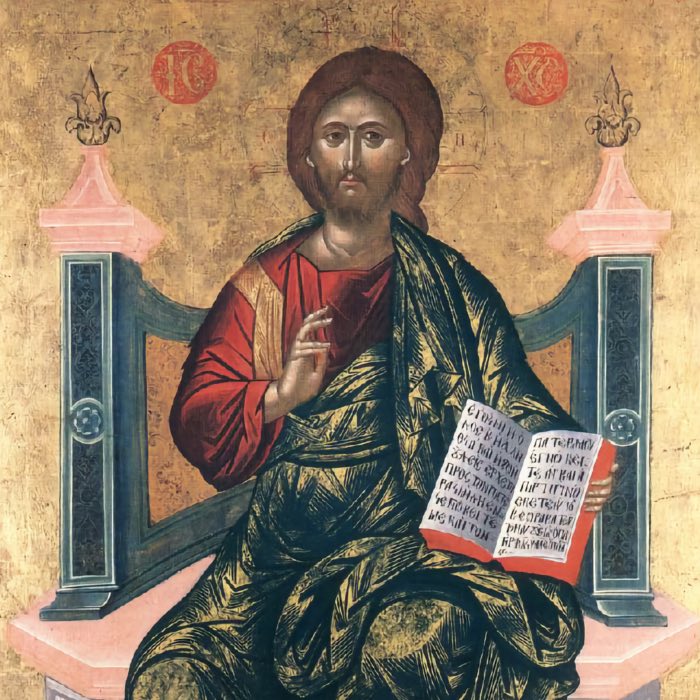

From the 4th century CE onwards, Christian leaders convened ecumenical councils to define and enforce orthodox dogma. The Councils of Nicaea (325), Constantinople (381), and Chalcedon (451) were pivotal in codifying doctrines such as the Trinity and Christ’s dual nature. These dogmas were no longer subjects of open inquiry but declarations of absolute truth. Dissenters, including Arian Christians, Nestorians, and Monophysites, were labeled heretics and subjected to persecution.

This shift transformed dogma from a shared framework for exploring truth into a tool for enforcing unity and suppressing dissent, paving the way for authoritarian structures within the Church.

The instrumentalization of dogma by Church authorities

As the Church authorities consolidated power during the Middle Ages, dogma became a central instrument for maintaining ecclesiastical control. The Church wielded dogmatic authority to dictate not only theological beliefs but also social and moral norms. This instrumentalization had far-reaching consequences, particularly in the justification of persecution and violence.

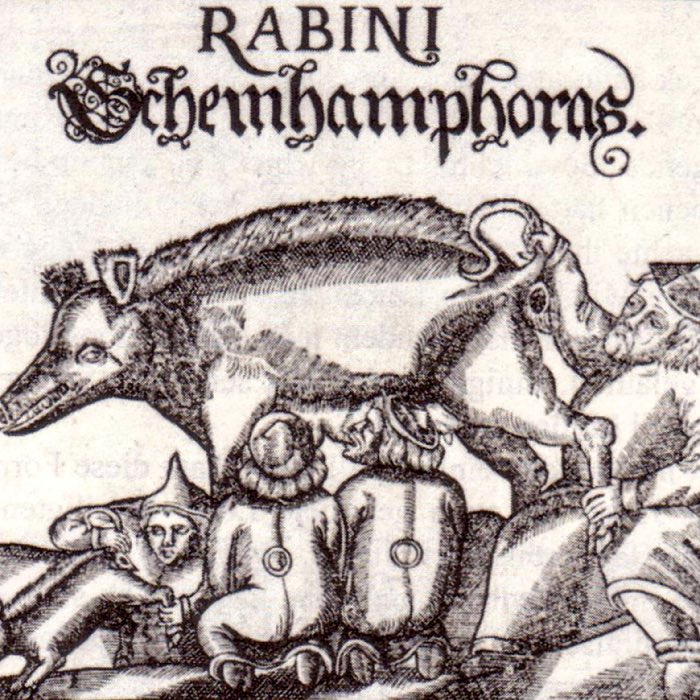

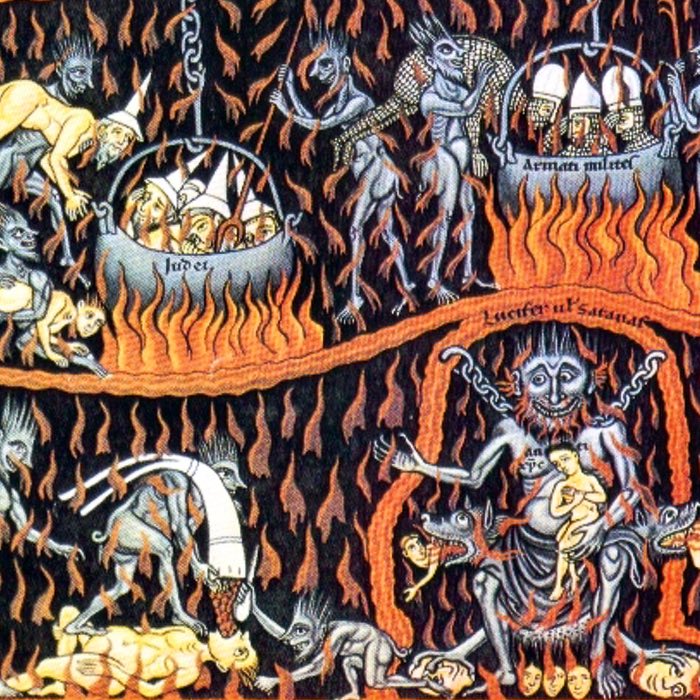

Fanatical pogroms and anti-semitism

The Church’s dogmatic teachings about Jews as “Christ-killers” and their alleged culpability for rejecting Jesus as the Messiah fostered centuries of systemic anti-Semitism.

Augustine of Hippo argued that Jews were to be preserved as a “living witness” to their rejection of Christ, serving as proof of Christianity’s truth. This theology dehumanized Jews while justifying their subjugation.

During the Crusades and later periods, Church rhetoric incited pogroms against Jewish communities in Europe, portraying them as enemies of Christendom. These massacres were framed as acts of religious purification, aligning with dogmatic imperatives.

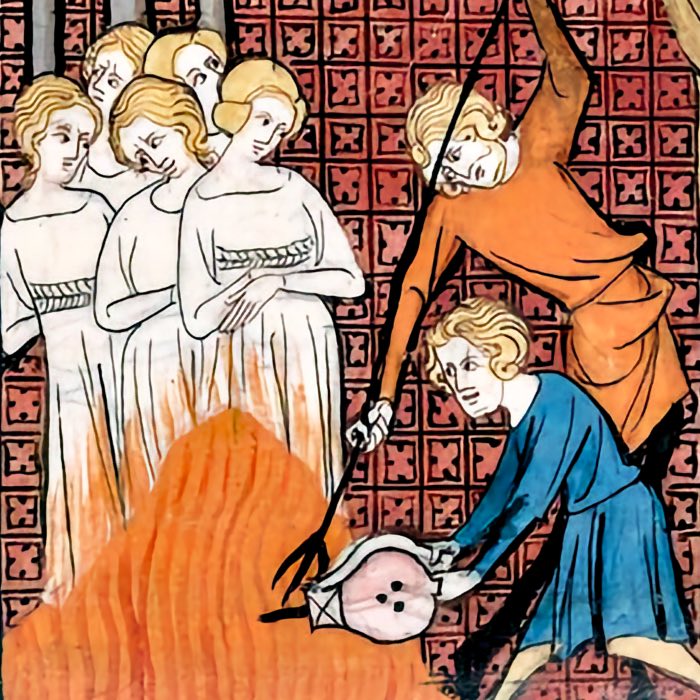

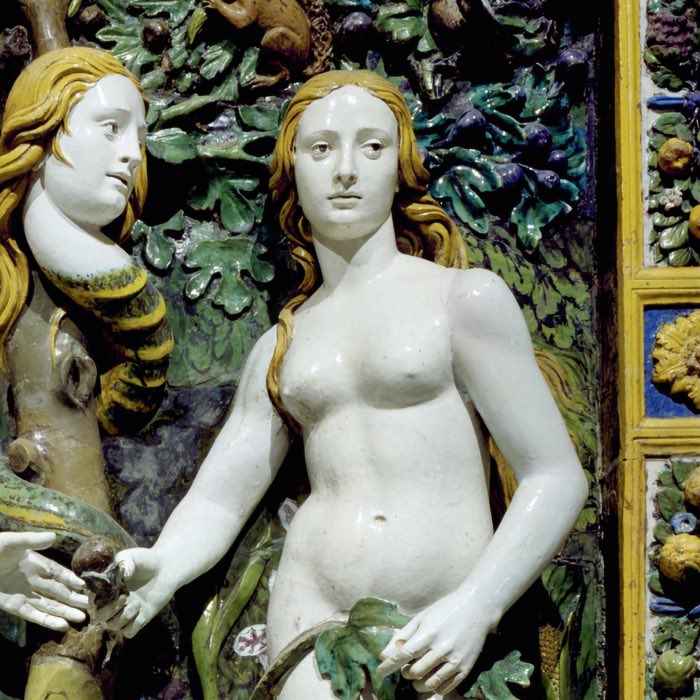

Witch hunts and the persecution of women

The Church’s dogmatic interpretation of evil and sin extended to the demonization of women, particularly those who deviated from societal norms.

For instance, the Malleus Maleficarum, published in 1487 by Heinrich Kramer, was a dogmatic treatise that fueled the witch hunts of the early modern period. This infamous treatise on witchcraft reflected and reinforced dogmatic dogmatic views of women as inherently susceptible to the devil’s influence.

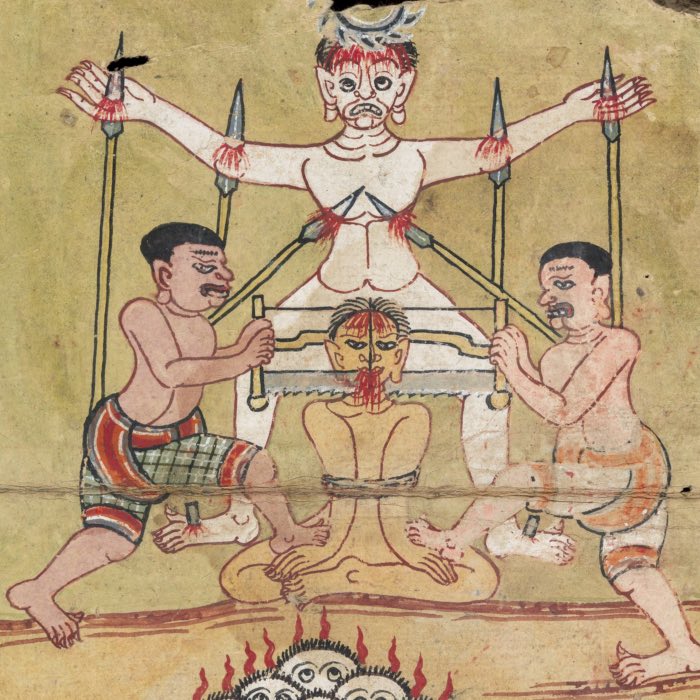

Another example is the Inquisition, which targeted alleged witches, often relying on fabricated confessions and supernatural accusations. Dogma provided the theological framework for these trials, portraying them as necessary to protect the community from spiritual corruption.

Hatred of homosexuality

The Church’s interpretation of biblical texts, combined with its dogmatic enforcement of heteronormativity, led to widespread persecution of homosexual individuals. Rooted in the Church’s dogmatic teachings, laws against “sodomy” criminalized same-sex relationships, framing them as violations of divine order. Homosexuals were often publicly executed, with Church authorities sanctioning these acts as moral and divine justice.

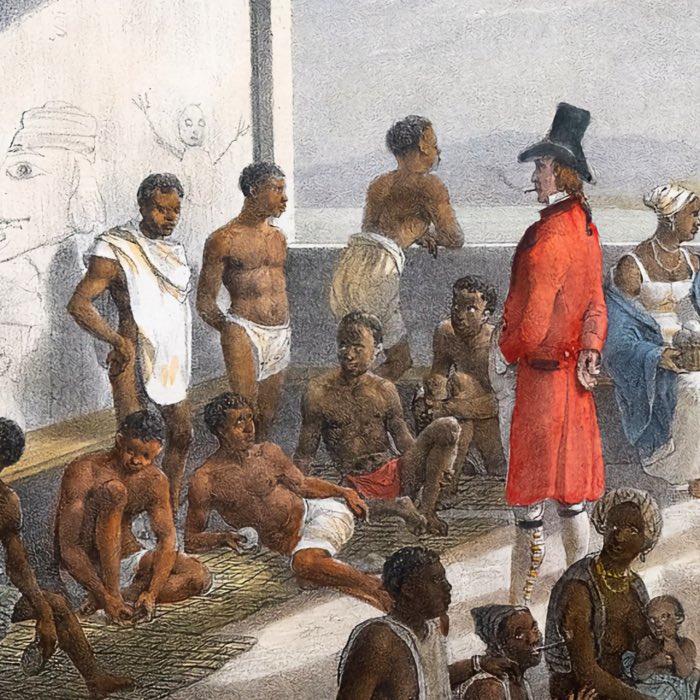

The ideological incitement of the faithful

The instrumentalization of dogma extended beyond direct acts of violence to the cultivation of an ideological framework that incited the faithful to participate in or tolerate such actions:

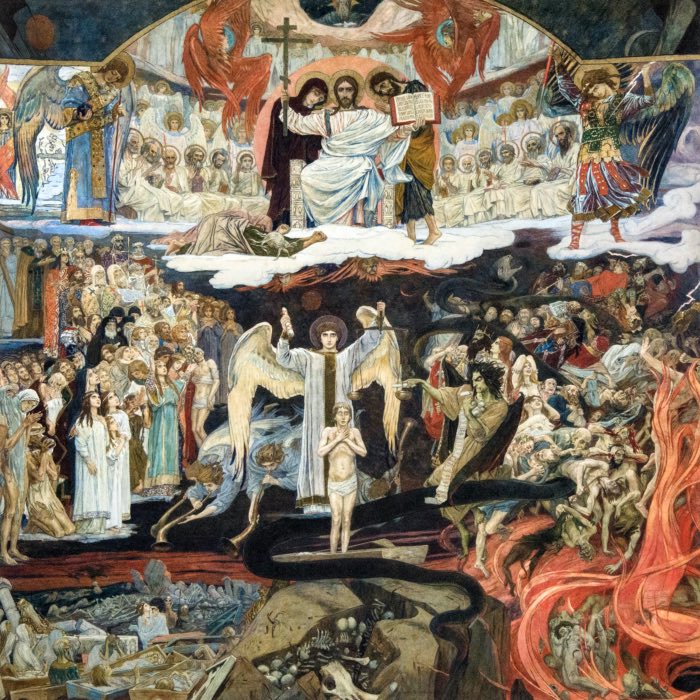

- Fear of damnation: The Church used dogmatic teachings about eternal punishment to compel obedience and suppress dissent. The fear of hell reinforced loyalty to ecclesiastical authority.

- Us vs. them mentality: Dogma often defined outsiders — whether heretics, Jews, witches, or others — as enemies of the faith. This dualistic worldview fostered division and justified violence against perceived threats.

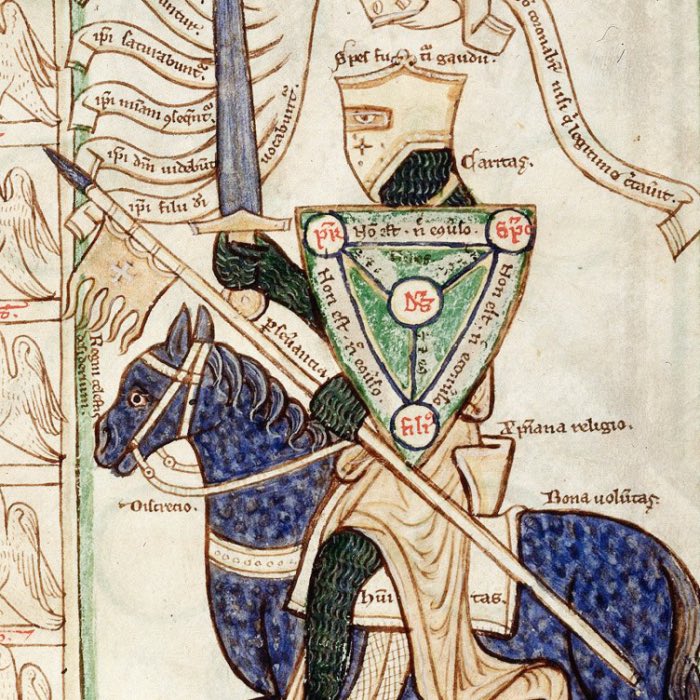

- Sanctification of violence: Crusades, holy wars, pogroms, and inquisitions were framed as acts of spiritual warfare, aligning them with the Church’s dogmatic mission. The faithful were promised absolution and divine favor for participating.

Contradictions with initial Christian values

The dogmatic and often violent practices of the Church authorities starkly contrasted with the core teachings of Jesus, which emphasized love, compassion, and humility. The Church’s instrumentalization of dogma represents a fundamental departure from these principles:

- Non-violence: Jesus’ call to “turn the other cheek” (Matthew 5:39) was replaced by the Church’s sanctioning of violence in the name of orthodoxy.

- Inclusivity: Jesus’ message of universal love and acceptance was overshadowed by the Church’s exclusionary practices and persecution of marginalized groups.

- Personal transformation: The emphasis on external dogmatic conformity diminished the focus on inner spiritual growth and moral action.

Examples of resistance to dogmatic enforcement

While the institutional Church often wielded dogma as a tool of control, there were individuals and movements within Christianity that resisted its rigidity and emphasized personal spirituality, inclusivity, and critical engagement with faith. These acts of resistance highlight an enduring tension between institutional authority and alternative approaches to faith and theology.

The mystics: Beyond dogma into direct experience

Christian mystics such as Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich, and Teresa of Ávila represent a profound challenge to dogmatic rigidity. Their writings and practices emphasized a direct, personal encounter with the divine, often bypassing the need for intermediaries or institutional structures. Meister Eckhart, for instance, advocated for the realization of the divine within each individual, a perspective that clashed with the hierarchical and externalized teachings of the Church. His ideas drew accusations of heresy, illustrating the Church’s discomfort with spiritual perspectives that threatened its dogmatic control.

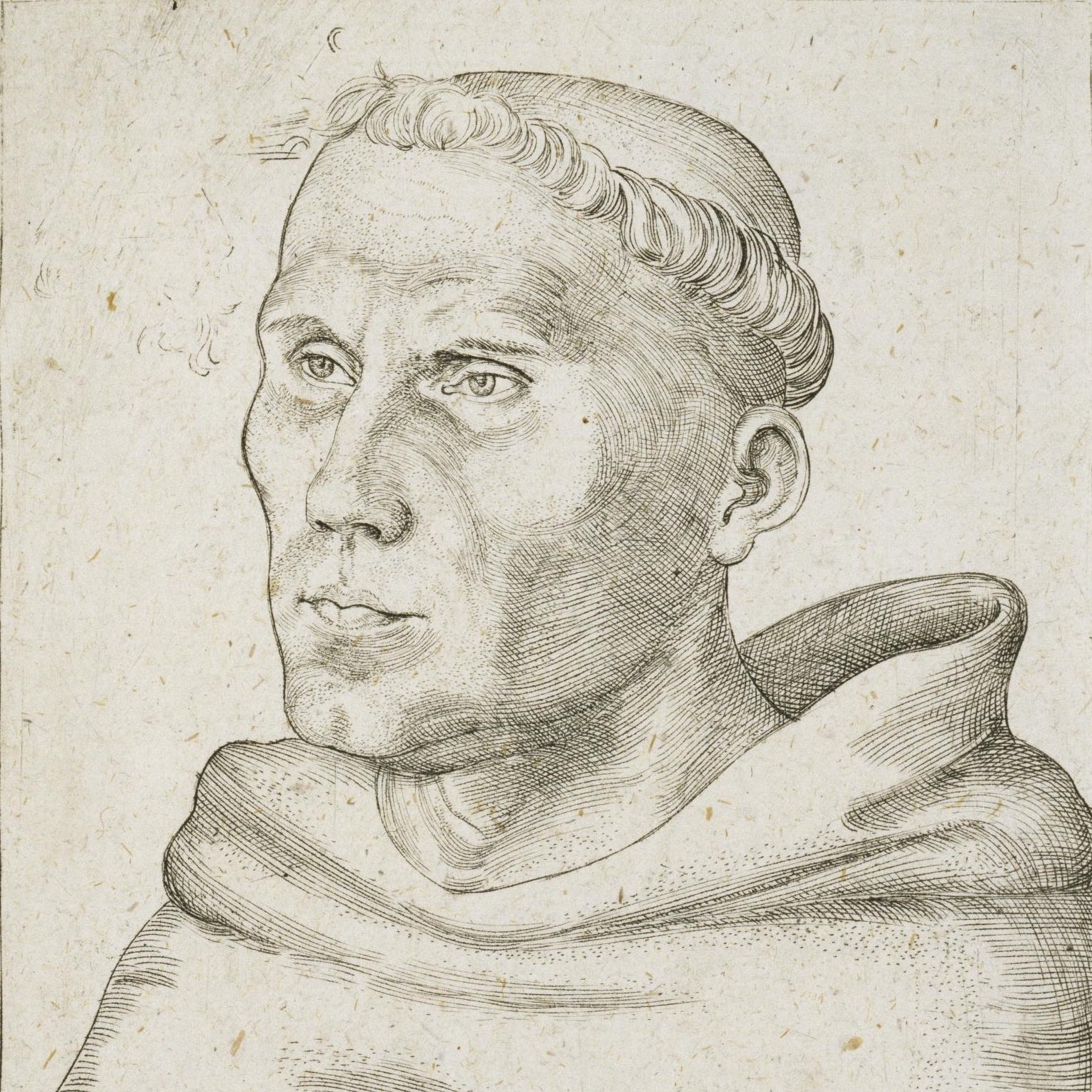

The Protestant Reformation: A revolt against centralized dogma

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century is one of the most significant examples of resistance to dogmatic enforcement. Reformers like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli rejected the authority of the Catholic Church to define and enforce doctrine, particularly on matters like indulgences, salvation, and access to scripture. Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible into vernacular languages empowered laypeople to engage with scripture directly, bypassing the Church’s monopoly on theological interpretation. Although the Reformation led to the establishment of new forms of dogma within Protestantism, it significantly fractured the Church’s ability to impose a singular orthodoxy.

Heretical movements and free thinkers

Throughout history, many so-called heretical movements resisted dogmatic authority. The Cathars, for example, rejected the materialism and corruption they perceived in the Catholic Church, advocating for a return to simplicity and spiritual purity. Similarly, thinkers like Giordano Bruno and Galileo Galilei challenged dogmatic interpretations of scripture that conflicted with scientific discoveries, facing persecution but paving the way for a broader acceptance of reason and inquiry within Christian thought.

Liberation theology: A modern challenge to orthodoxy

In the 20th century, liberation theology emerged as a resistance movement against traditional dogmatic structures, particularly in Latin America. Figures like Gustavo Gutiérrez called for a reinterpretation of Christian doctrine to focus on the plight of the poor and oppressed, emphasizing praxis over dogmatic adherence. This movement directly challenged the hierarchical Church’s complicity with political and economic systems of oppression, arguing for a faith rooted in justice, equality, and active social engagement.

Conclusion

The evolution of dogma from a Hellenistic tool of inquiry to a mechanism of control within the Church authorities underscores the complex interplay between religion and power. While dogma provided a framework for theological cohesion, its instrumentalization enabled centuries of persecution, violence, and ideological incitement. The tension between dogmatic orthodoxy and the teachings of Jesus highlights the enduring struggle between institutional authority and spiritual authenticity within Christianity. I think, that understanding the historical development of dogma is essential for critically engaging with the complexities of religious tradition and its impact on society.

References and further reading

- Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament, 2011, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199739783

- Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus became God – The exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee, 2014, Harper Collins, ISBN: 9780062252197

- Hurtado, L. W., Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, 2005, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, ISBN: 978-0802831675

- James D. G. Dunn, Did the First Christians Worship Jesus? The New Testament Evidence, 2010, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664231965

- Maurice Wiles, The Making of Christian Doctrine, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521099622

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 1 Die Frühzeit, 1996, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012632

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 2 Die Spätantike, 1996, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499601422

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 9 -Mitte des 16. bis Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vom Völkermord in der Neuen Welt bis zum Beginn der Aufklärung, 2010, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499624438

comments