Desert Fathers and the beginnings of Christian monasticism

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics who sought to withdraw from society to live a life devoted to prayer, contemplation, and spiritual discipline. Emerging in the 3rd century CE, primarily in the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, these individuals laid the foundations for Christian monasticism. Their pursuit of a deeper spiritual connection through solitude and meditation mirrors practices found in Buddhist monastic traditions, which also emphasize inner transformation through disciplined contemplation.

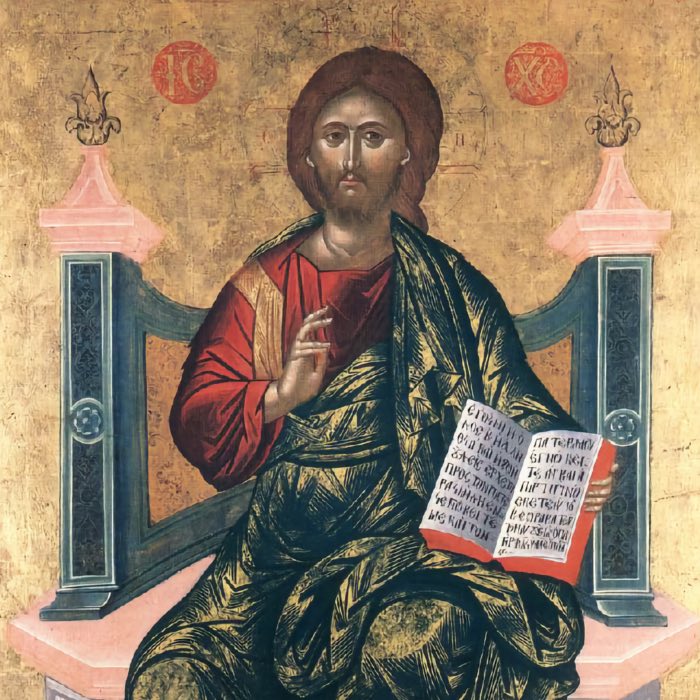

4th-century Desert Father from Ethiopia Saint Onuphrius, lived in seclusion in the desert of Upper Egypt, icon from 1662. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Who were the Desert Fathers?

The Desert Fathers were a loosely connected group of Christian ascetics who retreated to the deserts during the early centuries of Christianity. Their movement began with figures like Antony the Great (c. 251–356 CE), who is often considered the father of Christian monasticism. These early monks sought to emulate the life of Christ by renouncing worldly possessions, practicing asceticism, and dedicating their lives to prayer and contemplation.

Antony the Great sold his possessions and distributed the proceeds to the poor, embarking on a life of isolation in the Egyptian desert. There, he engaged in constant prayer and spiritual struggle. His life, as recounted by Athanasius in The Life of Antony, became a highly influential model for Christian monasticism, inspiring countless others to follow a similar path.

Another key figure, Pachomius (c. 292–346 CE), established the first organized Christian monastic communities. He created a structured form of communal living, with rules governing prayer, work, and study. This system introduced a balance of solitude and community life that shaped later monastic traditions.

Evagrius Ponticus (345–399 CE), a theologian and monk, contributed significantly to the intellectual and spiritual framework of early monasticism. He developed a systematic approach to contemplative prayer and inner purification, emphasizing the need to overcome the “passions” to achieve spiritual union with God. His teachings became foundational for later Christian contemplative practices.

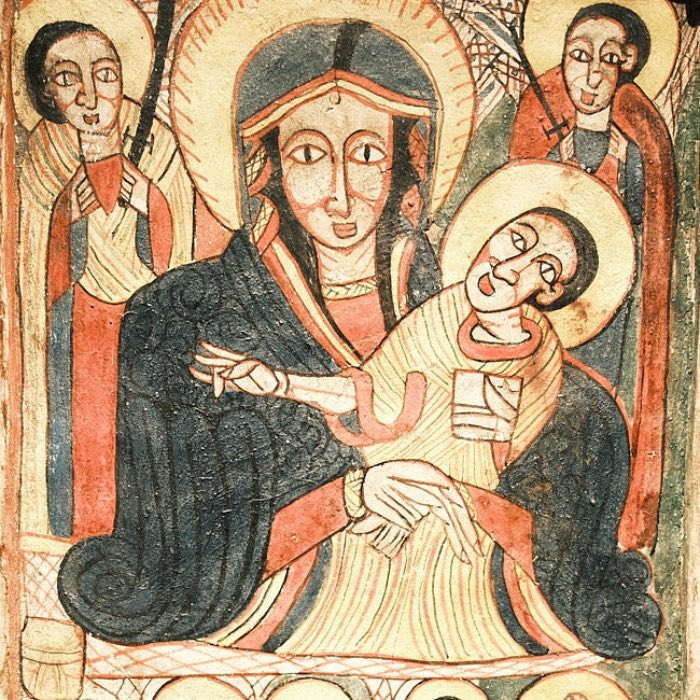

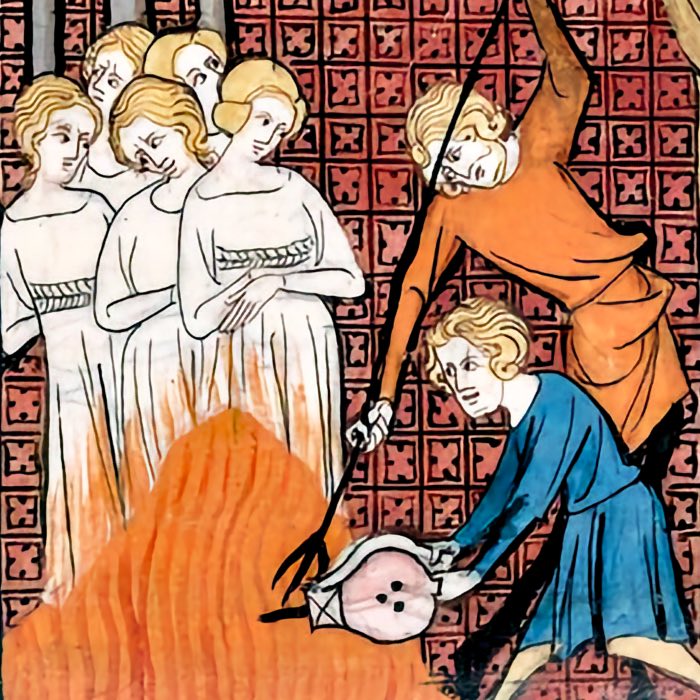

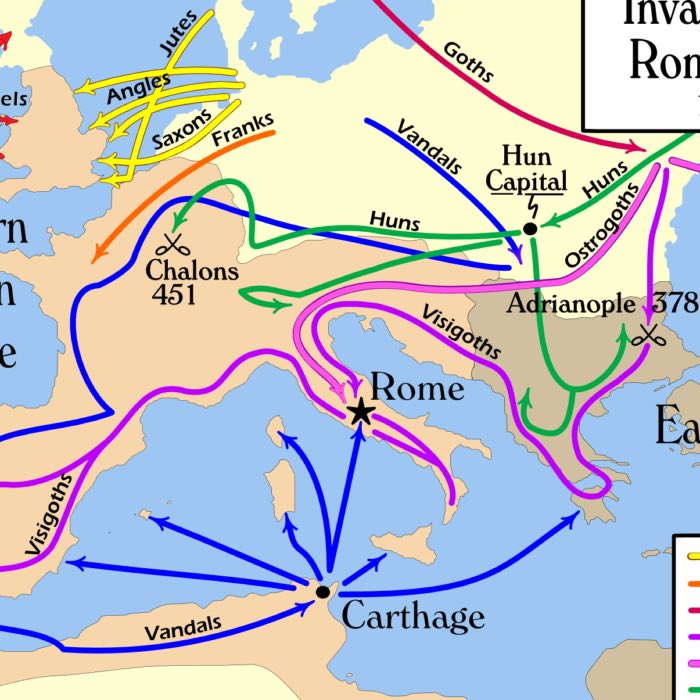

Episodes from Eremitic Life, Paolo Uccello, 1460. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Desert Fathers lived either as solitary hermits or in loosely organized communities. They practiced extreme forms of asceticism and sought divine wisdom through rigorous contemplation and spiritual discipline.

Core practices of the Desert Fathers

The spiritual practices of the Desert Fathers centered on detachment from the material world, inner purification, and communion with God through prayer and contemplation:

- Silence and solitude

Silence (hesychia) and solitude were considered essential for focusing the mind and spirit. The Desert Fathers believed that retreating from the distractions of the world allowed for a deeper encounter with God. - Prayer and meditation

Continuous prayer was a hallmark of their spirituality. They often used short, repetitive prayers — precursors to the later “Jesus Prayer” (“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner”) — to achieve a meditative state. - Asceticism

Fasting, self-denial, and rigorous discipline were employed to overcome physical desires and focus on spiritual growth. Ascetic practices were not seen as ends in themselves but as tools for attaining spiritual clarity and humility. - Scriptural reflection

The Desert Fathers engaged deeply with Scripture, using it as both a guide for moral living and a source of contemplative focus. - Overcoming the “passions”

Evagrius Ponticus categorized eight “thoughts” or “passions” (precursors to the Seven Deadly Sins) that distracted the soul. Overcoming these passions through mindfulness and prayer was central to their spiritual practice.

The Desert Fathers and early Christian contemplation

The practices of the Desert Fathers laid the groundwork for Christian contemplative traditions. Their focus on inner silence, prayer, and detachment evolved into later monastic systems, such as the Rule of St. Benedict, and influenced mystics like John Cassian and the authors of the Philokalia.

Their approach to contemplation shared several key elements with broader mystical traditions, emphasizing:

- Inner stillness: The cultivation of silence as a path to divine presence.

- Self-discipline: The use of ascetic practices to purify the soul and overcome distractions.

- Direct experience of God: A focus on personal communion with the divine rather than external rituals.

Parallels with Buddhist monks

The lives and practices of the Desert Fathers bear striking similarities to those of Buddhist monks, despite their different cultural and religious contexts. Both traditions emphasize renunciation, meditation, and the pursuit of inner transformation.

- Solitude and renunciation

Like the Desert Fathers, Buddhist monks often retreat to isolated locations to cultivate spiritual insight. The Buddha himself emphasized the renunciation of worldly possessions and attachments as essential for spiritual awakening. Both traditions view solitude not as escapism but as a means to confront inner struggles and achieve clarity. - Meditative practices

The Desert Fathers’ practice of hesychia (inner silence) parallels Buddhist meditation practices aimed at calming the mind and attaining mindfulness. The repetitive Jesus Prayer, for example, echoes the use of mantras in Buddhist meditation. Additionally, Evagrius Ponticus’ teachings on overcoming the “passions” align closely with the Buddhist practice of uprooting mental defilements such as greed, hatred, and delusion. - Ethical discipline and compassion

Both traditions also stress the importance of ethical living as a foundation for spiritual practice. The Desert Fathers’ care for the poor and their emphasis on humility resonate strongly with the Buddhist concept of metta (loving-kindness) and the compassionate actions of monks. - Spiritual hierarchies

In both Christianity and Buddhism, spiritual communities often formed around charismatic teachers, leading to the establishment of hierarchical structures. Antony the Great, for instance, attracted disciples, much like early Buddhist teachers gathered followers.

Despite these parallels, there are significant differences. Christian contemplation focuses on union with a personal God, while Buddhist meditation often aims for enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of suffering. Additionally, the Desert Fathers sometimes practiced extreme physical austerities, such as prolonged fasting and self-imposed hardships, which were less emphasized in mainstream Buddhist monasticism.

Legacy of the Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers played a pivotal role in shaping Christian monasticism and contemplative spirituality. Their practices continue to inspire modern Christians seeking a deeper spiritual life, particularly in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, which emphasizes hesychasm (prayerful silence) as a path to divine union.

The parallels with Buddhist monasticism suggest that the human quest for spiritual transformation transcends cultural and religious boundaries. Both traditions highlight the power of solitude, meditation, and ethical discipline to transform the heart and mind.

Conclusion

The Desert Fathers’ radical commitment to prayer, asceticism, and contemplation laid the foundation for Christian monasticism and contemplative spirituality. Their lives of solitude and self-denial reflect a universal human longing for deeper meaning and connection with the divine. By withdrawing from society to seek God in the silence of the desert, these early ascetics left a profound impact on the history of Christianity. Reflecting on the broader (criminal) history of the Catholic Church, one might argue that Christian authorities could have been far better served by following the path of the Desert Fathers — in a profoundly proverbial sense.

References and further reading

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 4 Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

comments