Foundation of Christian antisemitism and the role of Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) stands as one of the most influential figures in Christian theology, shaping doctrines that would dominate Western Christianity for centuries. However, his writings also laid the groundwork for one of the darkest legacies of Christian history: the theological marginalization and vilification of Jews. While Augustine did not advocate violence against Jews and even sought to limit persecution, his theological framework contributed to the embedding of antisemitism into Christian thought, particularly through his concept of Jews as “witnesses” to the truth of Christianity.

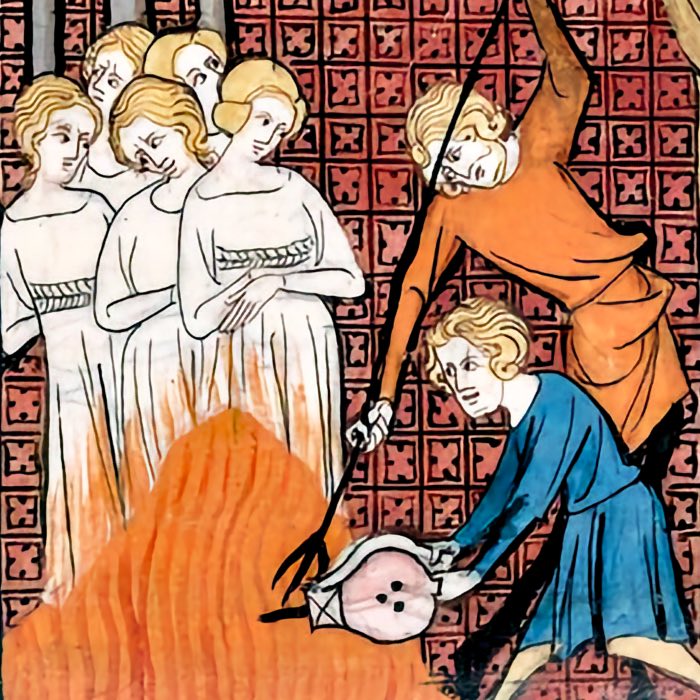

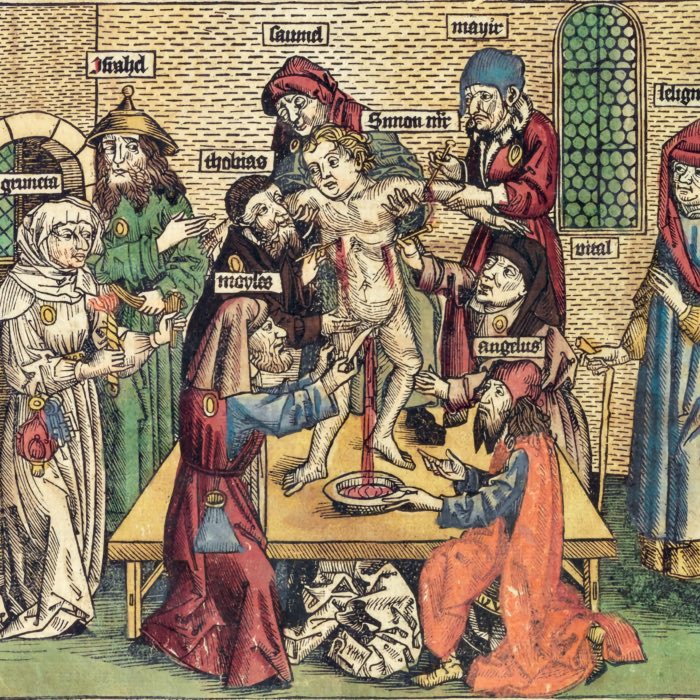

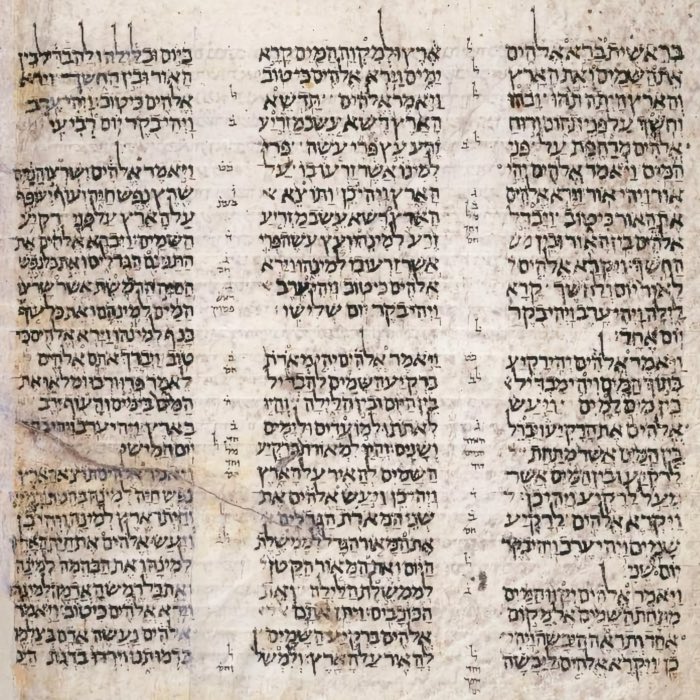

Depiction of the Extermination of the Deggendorf Jews in Schedel’s World Chronicle of 1493. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical context

By Augustine’s time, Christianity had risen to prominence as the official religion of the Roman Empire, replacing paganism as the dominant religious force. This shift created a complex relationship between Christians and Jews. Early Christians, including Augustine, inherited a dual legacy from their Jewish roots: reverence for the Hebrew Scriptures as sacred texts and a growing hostility toward Jews as a community that rejected Jesus as the Messiah.

Theologically, this tension was exacerbated by the need to explain why the Jews — YHWH’s chosen people — had not accepted Jesus. Augustine, along with other Church Fathers, developed a narrative that sought to reconcile the rejection of Jesus by the Jews with the legitimacy of Christian claims to fulfillment of Jewish prophecy.

Early antisemitic tendencies in Christianity

Anti-Jewish rhetoric existed in Christianity long before Augustine. Early Church Fathers such as Justin Martyr, Tertullian, and John Chrysostom used polemics against Jews in their writings. These figures portrayed Jews as Christ-killers, spiritually blind, or rejected by God. The New Testament itself contains passages that have been interpreted as hostile to Jews, including:

- Matthew 27:25: “His blood be on us and on our children”

This verse is part of the trial of Jesus before Pilate, where the crowd of Jews, according to the Gospel, accepts responsibility for Jesus’ crucifixion. It has historically been used to justify the notion of collective Jewish guilt for deicide. - John 8:44: “You are of your father the devil”

Here, Jesus is depicted as speaking to a group of Jews, accusing them of spiritual blindness and aligning them with the devil. This verse has been used to portray Jews as inherently opposed to God and truth.

Passages like these were later used to justify antisemitism. Reasons for this early antisemitism can be seen in the struggle of early Christians to define their identity in relation to Judaism and the Roman Empire. This competition influenced the development of anti-Jewish rhetoric, but it can’t serve as an excuse for a religion claiming to be based on love and compassion.

It thus seems that antisemitism was not a later evolution but an intrinsic component of Christianity’s theological foundation. It was there from the very beginning, integral to the faith’s self-definition. Over time, it became more pronounced and systematized, and figures like Augustine played a crucial role in this process.

Someone might raise the argument that “Jesus” taught the universal salvation and inclusion of all people. But if someone carefully reads the Gospels, they will find that this universal salvation had a condition: the acceptance of Jesus as the Messiah, thus the conversion to the Christian belief. The universal salvation was therefore not unconditional, and the rejection of Jesus as the Messiah was a reason for exclusion from this salvation. This conditionality of salvation was a theological justification for the general exclusion of those who did not accept Jesus as the Messiah, which included the Jews, but other marginalized groups such as pagans, heretics, homosexuals, women, and others.

Augustine’s theology of Jews: Witnesses, but marginalized

Augustine’s most influential contribution to Christian attitudes toward Jews was his doctrine of witness. In his seminal work, The City of God, Augustine argued that Jews played a unique role in Christian theology: they were “living relics”, preserved by God to bear witness to the truth of Christianity. He claimed that their continued existence served two purposes:

- Validation of Christian prophecy: According to Augustine, the survival of the Jewish people proved the legitimacy of Christianity, as their Scriptures contained the prophecies that Christians believed Jesus fulfilled. The Jews’ refusal to convert was seen as part of God’s divine plan, ensuring they would continue to “testify” to the truth of the Christian message.

- Punishment for deicide: Augustine also portrayed the suffering and dispersion of the Jews as divine punishment for their alleged role in the crucifixion of Jesus. While he did not advocate for active persecution, he viewed Jewish marginalization as a necessary condition of their role as witnesses.

This theological framework allowed Augustine to both condemn the Jews for their unbelief and argue for their preservation, creating a paradoxical position that would have far-reaching consequences.

While Augustine’s doctrine discouraged violence against Jews, it perpetuated their exclusion from full civic and religious participation. By framing Jews as spiritually blind and rejected by God, he legitimized their subordinate status within Christian society. This marginalization was seen as part of God’s divine plan, further embedding antisemitic attitudes into Christian theology.

Theological foundations of antisemitism

Augustine’s theology laid the groundwork for the development of Christian antisemitism in several key ways:

Supersessionism

Central to Augustine’s theology was the idea of supersessionism, the belief that Christianity had replaced Judaism as the true faith. Augustine argued that the covenant God made with the Jewish people had been fulfilled — and thus rendered obsolete — by the coming of Christ. While he affirmed the sacredness of the Hebrew Scriptures, he interpreted them as pointing toward Jesus, reducing their relevance outside of the Christian context.

This view positioned Judaism as a “rejected” religion, relegated to a lower status in God’s plan. Augustine’s supersessionist theology contributed to the perception of Jews as a people who had been abandoned by God, fostering attitudes of contempt and exclusion.

The “mark of Cain”

In his writings, Augustine occasionally drew on the Biblical story of Cain and Abel to symbolize the relationship between Jews and Christians. He likened the Jews to Cain, marked and exiled as punishment for killing his brother. This imagery reinforced the idea that Jewish suffering was both deserved and divinely ordained, further marginalizing them within Christian society. The “mark of Cain” was interpreted metaphorically as the Jews’ spiritual blindness and continued exile.

Long-term impact of Augustine’s views

While Augustine explicitly opposed the physical persecution of Jews, his theological framework had several unintended and devastating consequences:

- Institutionalized marginalization: By portraying Jews as necessary witnesses to Christian truth yet cursed and rejected, Augustine provided a theological rationale for their exclusion from mainstream society. This contributed to the institutionalization of discriminatory laws and practices in medieval Christendom.

- Fuel for pogroms and hatred: Augustine’s idea of Jewish suffering as divine punishment was easily co-opted by those seeking to justify violence against Jews. During the Crusades and other periods of unrest, this theological foundation was used to rationalize pogroms and massacres.

- Perpetuation of antisemitic tropes: Augustine’s emphasis on Jewish unbelief and their role in Jesus’ crucifixion reinforced enduring stereotypes of Jews as stubborn, blind, and cursed. These tropes persisted for centuries, shaping Christian attitudes and popular culture.

- Theological endurance: Augustine’s influence on Western Christianity ensured that his views on Jews were embedded in the theological tradition. His writings were widely cited by medieval theologians, including Thomas Aquinas, and remained a cornerstone of Christian teaching well into the modern era.

Critiques and modern reevaluations

In recent decades, Augustine’s views on Jews have come under scrutiny from theologians and historians. Many now recognize the harmful legacy of his teachings and their role in fostering antisemitism. Efforts by the Catholic Church, such as the Second Vatican Council’s Nostra Aetate (1965), have sought to repudiate supersessionism and promote a more positive relationship between Christians and Jews.

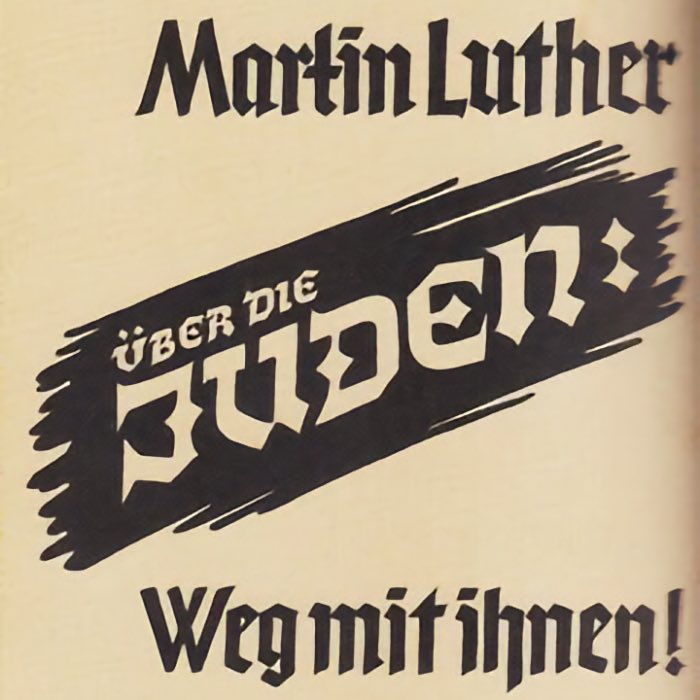

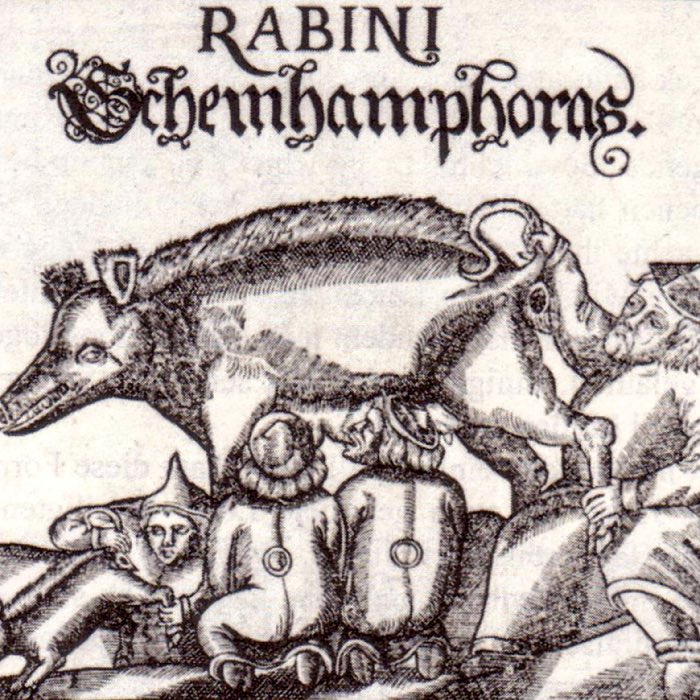

However, Augustine’s writings continue to provoke debate. While some scholars argue that his intention was to prevent violence against Jews by advocating their preservation, others contend that his theology laid the groundwork for centuries of marginalization and hostility, laying the path for the pogroms of the Middle Ages to Martin Luther’s antisemitic writings in the 16th century, which provided the theoretical framework for the 19th and 20th-century antisemitism and the Nazi ideology, culminating in the horrors of Holocaust.

Conclusion

Augustine of Hippo played a pivotal role in shaping Christian theology, and his views on Jews exemplify the complex and often contradictory legacy of his intellectual contributions. His doctrine of the “Jewish witness” placed Jews in a paradoxical position: necessary as living proof of Christian prophecy yet divinely punished and marginalized for rejecting Jesus as the Messiahs. By emphasizing their spiritual blindness and framing their suffering as a consequence of divine justice, Augustine contributed to the theological marginalization of Jews within Christian society. This marginalization was institutionalized in medieval Europe, reinforcing exclusionary practices that would persist for centuries.

While Augustine himself opposed violence against Jews and insisted on their preservation, his theological framework had far-reaching consequences that extended beyond his intentions. By formalizing supersessionism and associating Jewish suffering with divine punishment, Augustine provided a foundation for the systemic antisemitism that would manifest in later Christian thought and practice. His writings, revered for their theological depth, were instrumental in shaping the Christian worldview but also left a troubling legacy of exclusion and prejudice.

References and further reading

- Brown, P., Augustine of Hippo: A Biography, 2013, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520280410

- Chadwick, H., Augustine: A Very Short Introduction, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192854520

- Markus, R.A., The End of Ancient Christianity, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521339490

- Rist, J.M., Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521589529

- Dodaro, R., Christ and the Just Society in the Thought of Augustine, 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521841627

- Pelikan, J., The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), 1975, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226653716

- Augustine, Confessions, translated by H. Chadwick, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0241295793

- Augustine, The City of God, translated by R.W. Dyson, 1998, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521468435

- Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, translated by D.W. Robertson, 1958, Pearson, ISBN: 978-0024021502

- Augustine, De Trinitate (On the Trinity), translated by O. S. A John E. Rotelle, 2012, New City Press, ISBN: 978-1565484467

- Augustine, On Free Choice of the Will, translated by T. Williams, 1993, Hackett Publishing, ISBN: 978-0872201880

- O’Donnell, J.J., Augustine: A New Biography, 2006, Ecco, ISBN: 978-0060535384

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 4 Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 7 12. und 14. Jahrhundert: Von Kaiser Heinrich VI. (1190) zu Kaiser Ludwig IV. dem Bayern (1347), 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498013202

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Katz, Steven (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Antisemitism, 2022, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108714525

- Moore, R. I., The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250, 2006, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405129640

- Nirenberg, David, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, 2018, Head of Zeus, ISBN: 978-1789541168

comments