Theology of Augustine of Hippo

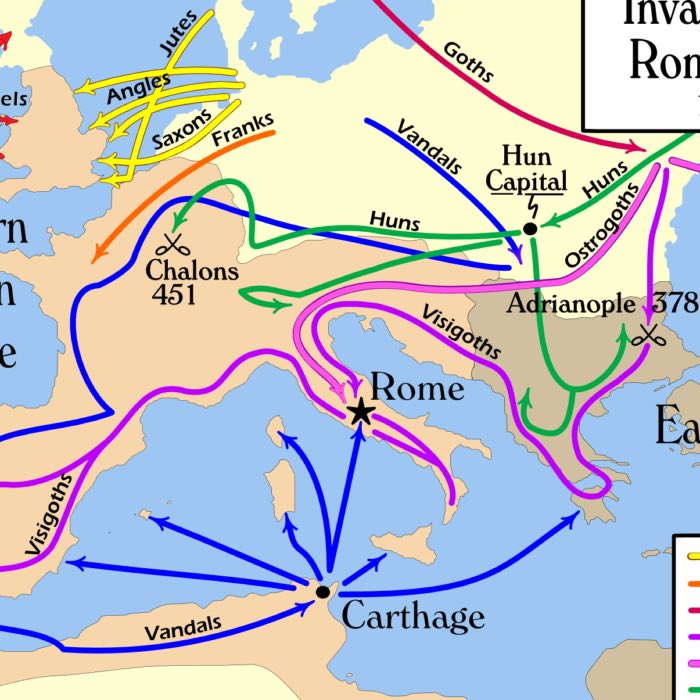

Augustine of Hippo stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of Western Christianity. Living during the tumultuous decline of the Roman Empire, he was both a witness to and a shaper of the theological and intellectual traditions that defined the Christian Church for centuries. Through his profound engagement with Neoplatonism, his theological innovations, and his prolific writings, Augustine laid the foundation for much of medieval and modern Christian thought. However, his legacy is not without its darker aspects: Augustine’s theology contributed to the dogmatization of Christianity, justified the consolidation of ecclesial authority, and perpetuated antisemitic attitudes through his doctrine of Jewish witness. In this post, we therefore explore Augustine’s life, his major philosophical and theological contributions, and his role in shaping the trajectory of Christian thought.

Augustine in the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

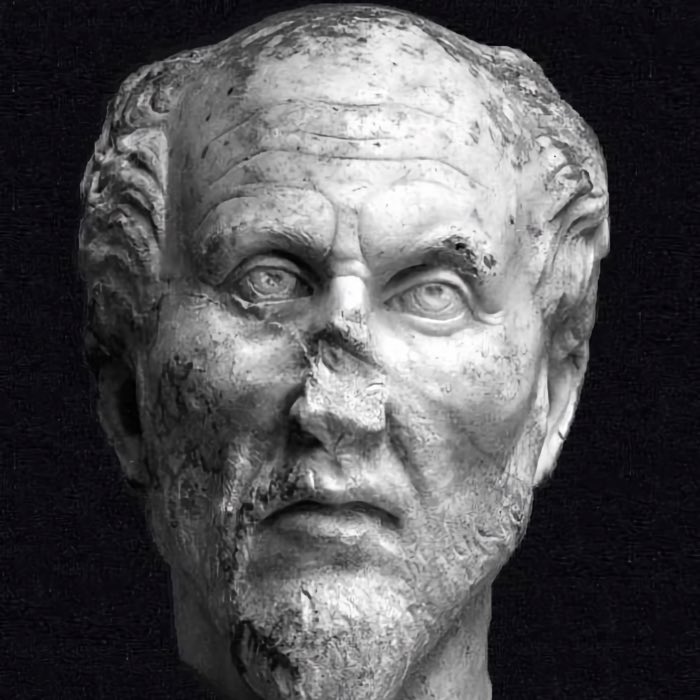

Augustine’s life and context

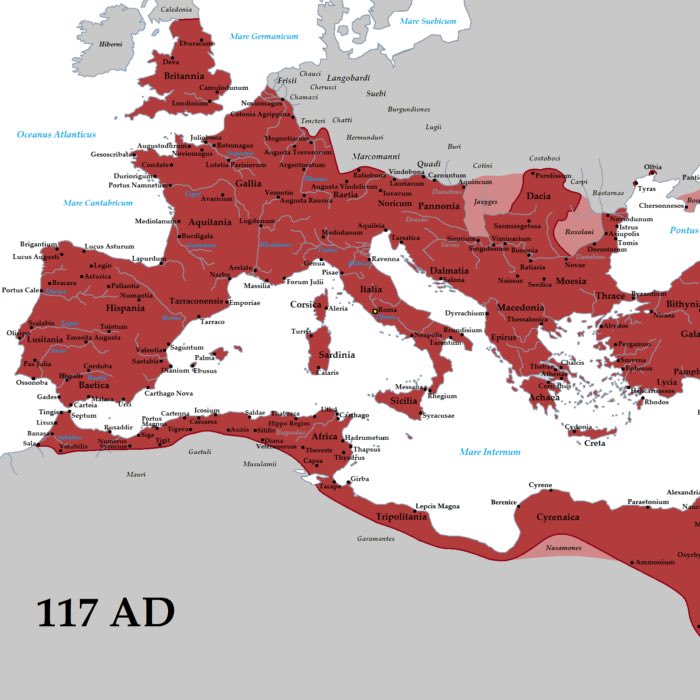

Augustine (354–430 CE) was born in Thagaste, a provincial Roman town in North Africa (modern-day Algeria), to a pagan father, Patricius, and a devout Christian mother, Monica. His upbringing reflected the cultural and religious diversity of the late Roman Empire, with its blend of traditional Roman religion, burgeoning Christianity, and Hellenistic philosophical traditions.

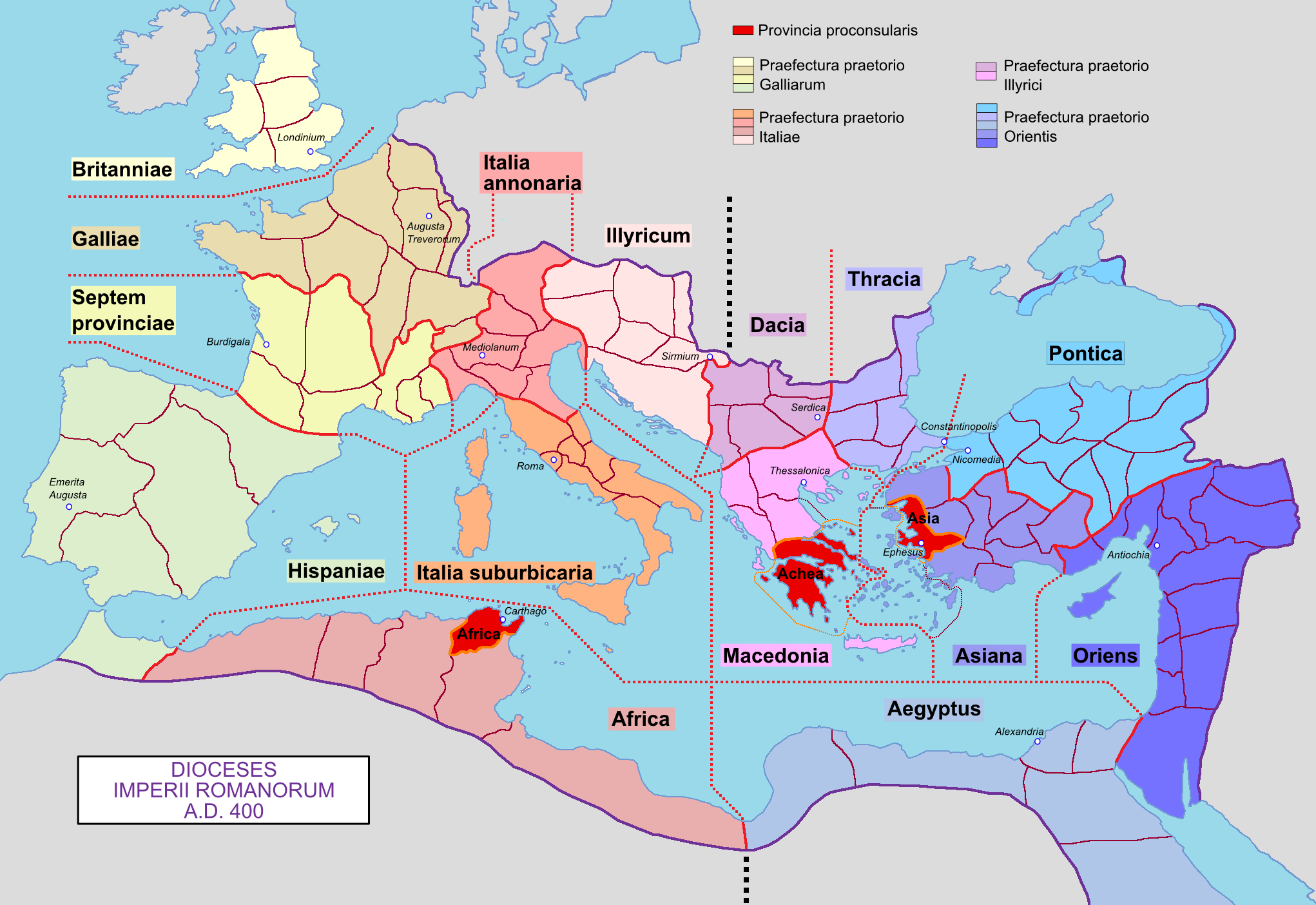

Map of the Roman Empire with its dioceses, around 400 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In his early years, Augustine pursued a classical education in rhetoric and philosophy, eventually becoming a teacher of rhetoric in Carthage, Rome, and Milan. During this time, he embraced Manichaeism, a dualistic religious movement that appealed to his intellectual curiosity and moral struggles. However, disillusionment with its doctrines led him to explore Neoplatonism, particularly through the writings of Plotinus. This philosophical framework profoundly influenced his eventual conversion to Christianity.

Under the guidance of Ambrose, the bishop of Milan, Augustine was baptized in 387 CE. After his conversion, he returned to North Africa, where he established a monastic community. He was later ordained a priest and eventually became the bishop of Hippo (modern-day Annaba, Algeria). As bishop, Augustine defended the Church against theological controversies, including Donatism and Pelagianism, and wrote extensively on matters of faith, philosophy, and scripture.

The Consecration of Saint Augustine by Jaume Huguet, around 1463-1470/1475. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Augustine’s later years were marked by the collapse of Roman authority in the West, a period that profoundly shaped his magnum opus, The City of God. He died in 430 CE during the siege of Hippo by the Vandals.

Augustine’s philosophy and theology

Augustine’s theological and philosophical contributions are wide-ranging and complex, reflecting his engagement with classical philosophy, Christian scripture, and the intellectual currents of his time. His works, including Confessions, The City of God, and De Trinitate, remain foundational texts in Christian theology and Western philosophy. In the following, we briefly explore some of the key aspects of Augustine’s thought.

Augustine in His Study by Vittore Carpaccio, 1502. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Influence of Platonism

Augustine’s engagement with Neoplatonism was pivotal in shaping his theological outlook. Through the works of Plotinus and the Christianized Platonism of Ambrose, Augustine developed a vision of God as the ultimate, unchanging source of all being and goodness. For Augustine, God was not only the creator but also the sustainer of the universe, analogous to The One in Neoplatonism. This philosophical grounding allowed Augustine to articulate complex theological concepts, such as the nature of the Trinity and the relationship between grace and free will.

The Two Cities theory

In The City of God, Augustine introduced his famous theory of the Two Cities: the City of God (Civitas Dei) and the City of Man (Civitas Terrena). These cities represent two opposing orientations: the City of God is characterized by love for God and a focus on eternal life, while the City of Man is driven by self-love and earthly desires. Augustine argued that history is the interplay of these two cities, with the Church serving as the earthly manifestation of the City of God. This framework provided a theological interpretation of the fall of Rome, portraying it as part of the divine plan rather than a catastrophic failure.

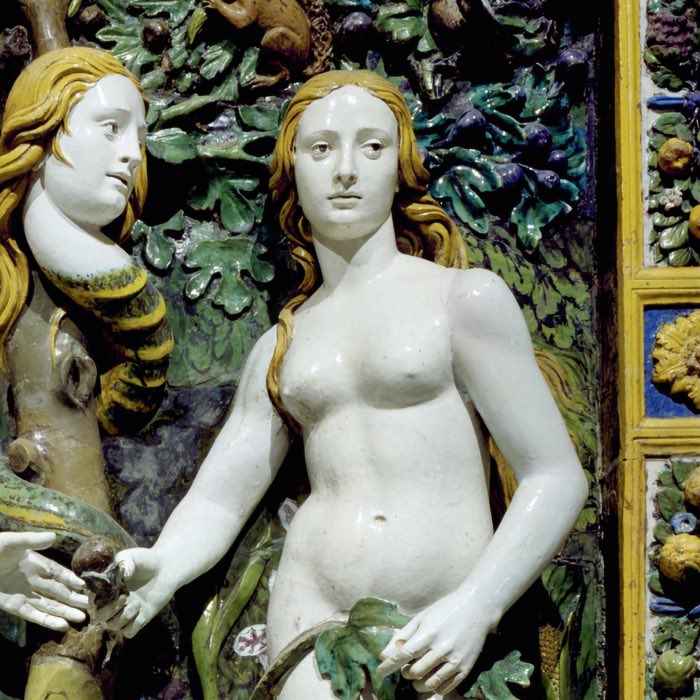

Original sin and grace

Augustine’s doctrine of original sin, based on his interpretation of Paul’s writings, posited that humanity inherited sin from Adam, resulting in a fallen nature and an inclination toward evil. For Augustine, salvation was possible only through divine grace, which could not be earned but was freely given by God. This emphasis on grace stood in opposition to Pelagianism, which held that humans could achieve salvation through their own efforts. Augustine’s arguments against Pelagianism solidified the Church’s teaching on the necessity of grace.

Free will and theodicy

Augustine grappled with the problem of evil, seeking to reconcile the existence of a good and omnipotent God with the presence of suffering and sin. He argued that evil is not a substance but a privatio boni — a lack or privation of good. According to Augustine, God created humans with free will, a gift that reflects divine love and enables genuine moral choice. However, the misuse of this freedom led to sin and evil, introducing suffering into the world.

Augustine maintained that God permits evil as part of a larger divine plan, in which even suffering and sin are ultimately directed toward a greater purpose, such as the moral and spiritual growth of humanity. In this framework, the existence of evil highlights the necessity of grace, through which individuals are redeemed and guided back to God. Augustine’s theodicy (defense of God’s goodness in the face of evil) became a cornerstone of Christian theology, trying to address the perennial tension between divine omnipotence and human freedom.

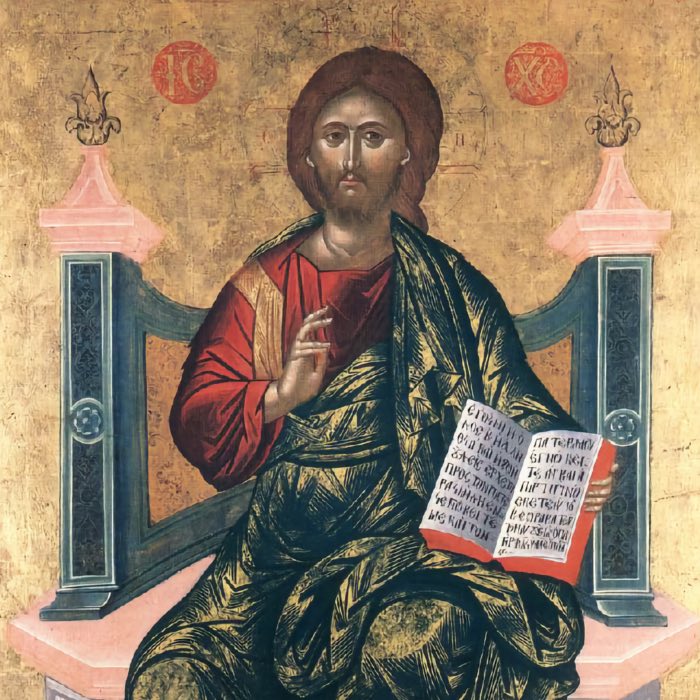

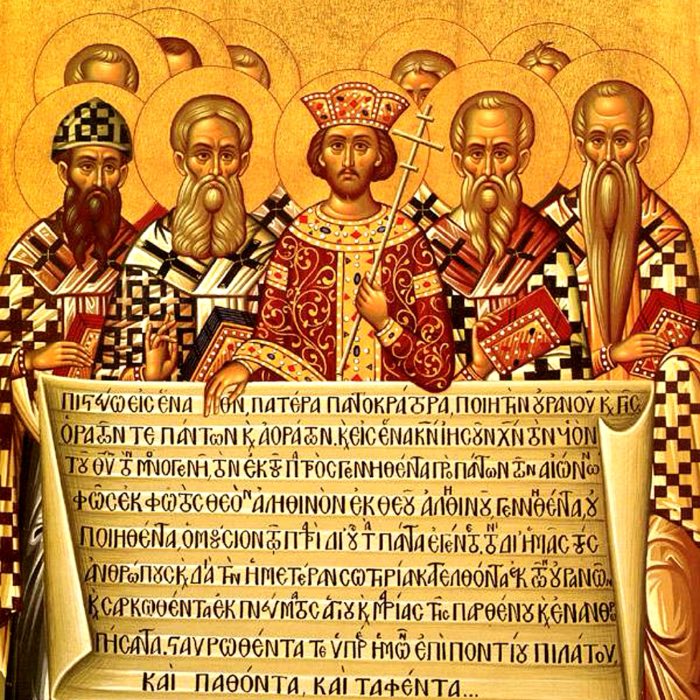

Trinity

In De Trinitate, Augustine articulated one of the most sophisticated early Christian understandings of the Trinity. He approached the Trinity as a unified yet distinct Godhead, consisting of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, co-equal and co-eternal. To explain this complex doctrine, Augustine employed analogies from human experience, such as the triad of memory, understanding, and will. These faculties of the human mind reflect the unity of essence and the distinction of persons within the divine nature. For Augustine, memory corresponds to the Father as the source of all, understanding aligns with the Son as the Word or logos, and will relates to the Spirit as the bond of love.

Augustine further argued that the relationships within the Trinity are defined by mutual love and self-giving. The Father begets the Son, the Son is begotten of the Father, and the Holy Spirit proceeds from both, emphasizing a dynamic yet harmonious interaction. This framework not only affirmed the equality of the divine persons but also clarified their relational roles without compromising their unity.

His work laid the groundwork for later Trinitarian theology, influencing both the Nicene tradition and medieval theological developments, and became a cornerstone of Western Christian thought.

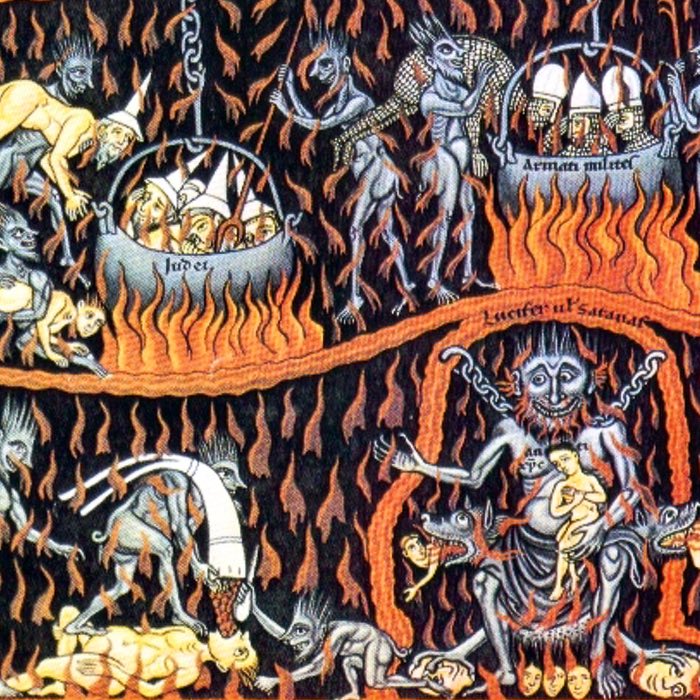

Concept of hell

Augustine’s understanding of hell as a place of eternal punishment for the unrepentant was influential in shaping Christian eschatology. He viewed hell as both a physical and spiritual reality, characterized by separation from God and the torment of eternal fire. This concept contrasted sharply with Origen’s vision of universal salvation (apokatastasis), which Augustine rejected as heretical. For Augustine, hell was a just consequence of free will and sin.

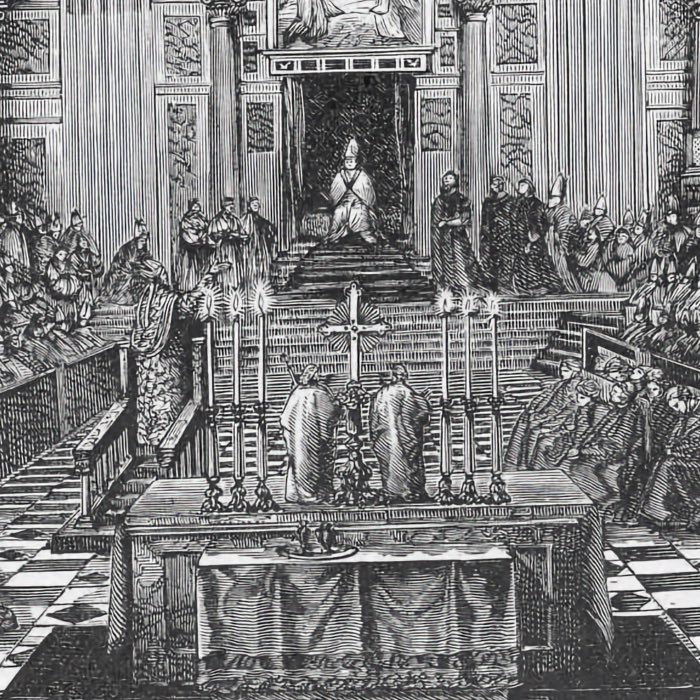

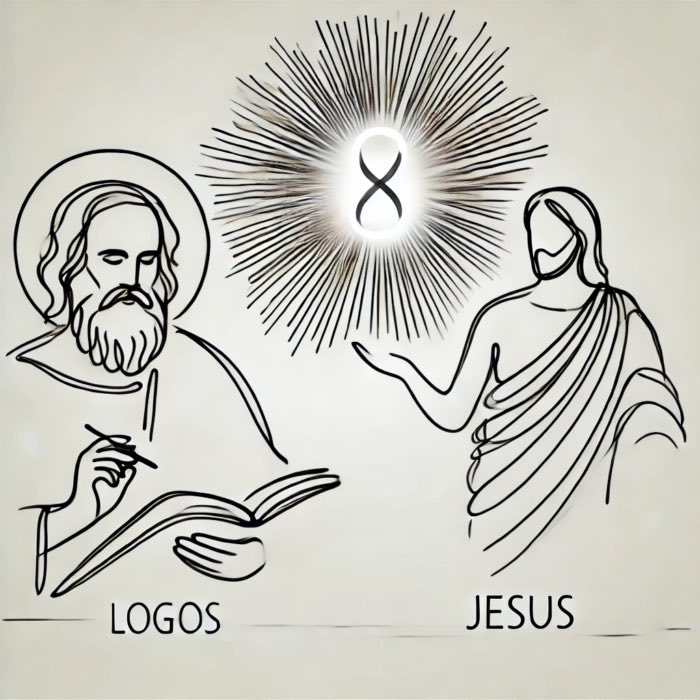

Role of the Church as mediator

Augustine emphasized the role of the Church as the sole mediator between God and humanity. While Origen had seen the logos as the mediator, bridging the divine and human realms through reason and wisdom, Augustine shifted this mediating role to the institutional Church. For Augustine, the Church was the visible body of Christ on Earth, dispensing grace through the sacraments and guiding believers toward salvation. This institutional focus reinforced the Church’s authority and hierarchical structure.

Antisemitism in Augustine’s theology

Augustine’s doctrine of Jewish witness posited that Jews should be preserved as a marginalized group to bear witness to the truth of Christian prophecy and the fulfillment of the Old Testament in Christ. He argued that the continued existence of Jews served as living proof of the validity of Christian scripture and the Church’s claims.

However, Augustine’s formulation relegated Jews to a subjugated status, portraying them as a people whose role in salvation history was limited to validating Christian truths rather than actively participating in them. While Augustine discouraged violence against Jews and opposed their forced conversion, he often depicted them as spiritually blind, hardened in their rejection of Christ, and punished for their collective “failure” to recognize Jesus as the Messiah. This theological perspective reinforced their marginalization in Christian societies and contributed to the entrenched antisemitic attitudes that characterized much of medieval Christendom.

Demonology

In his demonology, Augustine drew on Neoplatonic ideas of fallen spiritual beings. He described demons as angels who, through pride and rebellion, had fallen from grace. These demons actively tempted humans and worked against God’s divine order. Unlike Origen, who held a more optimistic view of eventual reconciliation, Augustine saw demons as irredeemable and eternally damned, reinforcing his vision of a cosmic struggle between good and evil.

Scripture and allegory

Augustine balanced literal and allegorical interpretations of scripture, employing allegory to reconcile difficult passages with Christian doctrine. For example, he interpreted the six days of creation in Genesis not as literal days but as a symbolic framework for God’s creative activity. His approach to scripture influenced medieval exegesis and remains a significant aspect of his theological legacy.

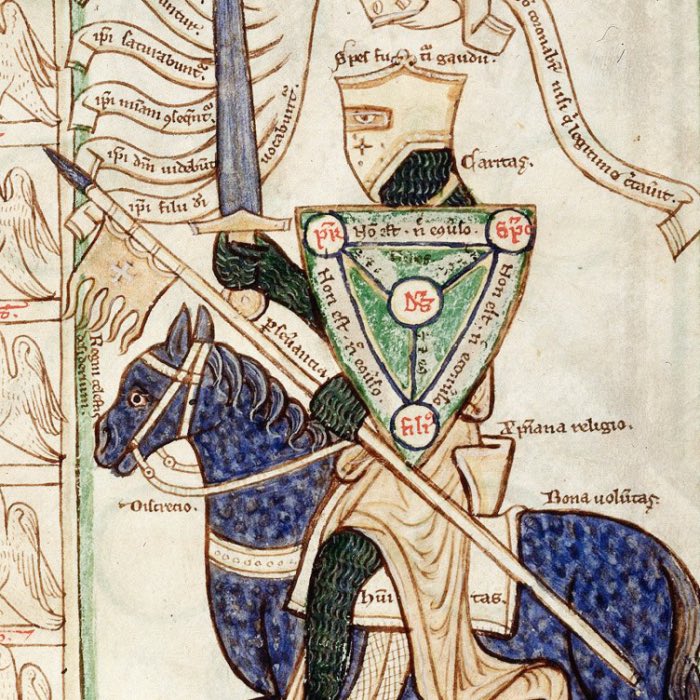

Concept of a Holy War

One of Augustine’s most significant and controversial theological innovations was his concept of the “holy war”, developed amidst the socio-political upheaval of his time. During the late Roman Empire, external invasions threatened the stability of Rome, and many Christians refused military service, citing Jesus’ teachings on non-violence, love, and compassion. This widespread reluctance among Christians posed a dual challenge: it undermined Rome’s ability to defend itself and complicated the Church’s growing alignment with the imperial structure.

In response, Augustine formulated a theological framework to justify war under specific circumstances. In The City of God, he argued that warfare could be morally acceptable if it served righteous purposes, such as protecting the innocent, maintaining peace, or defending the Church. He insisted that such wars must be waged with justice, motivated by love rather than hatred or vengeance. This framework not only accommodated the immediate needs of Rome but also laid the groundwork for the later Christian doctrine of “just war” theory.

Nevertheless, Augustine’s concept of holy war marked a dramatic shift from the core teachings of Jesus, who preached unconditional love and non-violence. The early Christians who refused to bear arms embodied these ideals more faithfully, prioritizing radical pacifism and compassion. By creating a theological justification for violence, Augustine’s innovation reflects how Christianity evolved to meet the demands of its historical and political context. His development of the holy war concept exemplifies the broader pattern of doctrinal adaptation, raising profound questions about whether Christianity has ever possessed a singular, unchanging essence.

Theological controversies

Augustine’s theological legacy was shaped by his engagement with various controversies that defined the early Church. His responses to these debates not only clarified his own theological positions but also influenced the development of Christian doctrine and practice.

Against the Manicheans

Augustine’s rejection of Manichaeism marked a significant turning point in his intellectual development. He criticized its dualistic worldview, arguing instead for the unity of God as the source of all good. His writings against the Manicheans laid the groundwork for his later theological positions on sin, grace, and free will. However, his engagement against Manichaeism also fueled Christian efforts to suppress and persecute perceived heretics, a trend that would continue throughout the medieval period.

Saint Augustine Disputing with the Heretics painting by Vergós Group, around 1470/1475-1486. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Donatist controversy

In his conflict with the Donatists, Augustine defended the unity of the Church and the validity of sacraments administered by sinful priests. He argued that the holiness of the Church depended not on the moral purity of its members but on the presence of Christ within it. This controversy highlighted Augustine’s institutional view of the Church as a means of grace.

The Pelagian controversy

Augustine’s opposition to Pelagianism centered on the necessity of divine grace for salvation. He argued that human will alone was insufficient to overcome sin and achieve righteousness. This debate solidified the Church’s stance on original sin and the indispensability of grace.

Differences between Augustine and Origen

Theological frameworks

Augustine and Origen represent two distinct approaches to Christian theology. Origen, heavily influenced by Platonic philosophy, emphasized the logos as the mediator between humanity and God. He saw salvation as a cosmic process, with universal restoration (apokatastasis) as its ultimate goal. Augustine, in contrast, rejected this optimistic view of universal salvation. He posited eternal damnation for the unrepentant and emphasized the institutional Church as the mediator of grace, rather than the logos. This shift reflects Augustine’s more hierarchical and institutional approach, as opposed to Origen’s mystical and philosophical orientation.

Free will and grace

While both thinkers addressed the relationship between free will and divine grace, they differed significantly. Origen upheld a strong belief in human freedom, asserting that souls could freely choose to return to God. Augustine, however, placed greater emphasis on divine grace as the decisive factor in salvation, arguing that human will alone was insufficient to overcome sin. This perspective emerged from his opposition to Pelagianism and became a cornerstone of Western Christian theology.

Eschatology

Origen’s vision of universal salvation starkly contrasts with Augustine’s theology of eternal damnation. For Origen, all souls, including demons, would eventually be reconciled to God. Augustine rejected this view, framing hell as an eternal state of punishment for those who rejected divine grace. This divergence had profound implications for Christian eschatology, with Augustine’s views becoming dominant in Western Christianity.

The role of the Church

Origen saw the logos as a rational and spiritual mediator guiding individuals toward God, emphasizing a personal, intellectual ascent. Augustine, on the other hand, elevated the institutional Church as the visible and sacramental body of Christ, through which grace was dispensed. This marked a significant departure from Origen’s more individualized, philosophical approach to spirituality.

How Augustine’s theology transformed Christianity

Augustine’s theological innovations profoundly shaped the development of Christianity, influencing its doctrines, practices, and institutional structures. His synthesis of classical philosophy and Christian theology laid the foundation for medieval scholasticism and shaped the trajectory of Western thought.

Saint Augustine in His Study by Sandro Botticelli, 1494, Uffizi Gallery. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

From a Jewish sect to a universal faith

Christianity began as a Jewish sect with elements resembling Greco-Roman mystery cults. Early beliefs focused on Jesus as a sacrificial figure for humanity’s salvation, tied closely to Jewish Messianic expectations. Augustine’s theology helped transform Christianity from this relatively narrow framework into a universal, systematic faith with broad appeal. However, one should not underestimate the role of Augustine’s predecessor in this process. Paul had already laid the groundwork for this transformation, as his writings emphasized the universal scope of salvation through Christ. And Origin was the first trying to bridge both, Paul’s invented Christianity with its Jewish roots and Hellenistic philosophy.

Institutionalization of the Church

Augustine’s emphasis on the Church as the mediator of grace solidified its role as the central institution of Christianity. By framing the Church as the visible representation of the City of God, he strengthened its authority and hierarchy, laying the groundwork for its dominance in medieval Europe.

Philosophical depth and theological systematization

Through his synthesis of Neoplatonism and Christian doctrine, Augustine provided Christianity with a philosophical depth that elevated it beyond its origins as a belief system rooted in myth and ritual. His doctrines on original sin, predestination, and grace introduced a level of theological sophistication that appealed to educated audiences and allowed Christianity to engage with Greco-Roman intellectual traditions.

Redefining human nature and salvation

Augustine redefined the human condition as inherently sinful due to original sin, making divine grace essential for salvation. This focus on human weakness and dependency on God reshaped the narrative of salvation, shifting it from a collective hope rooted in Jewish traditions to a deeply personal and universal struggle for redemption. This also allowed the Church to assert its role as the sole dispenser of grace, reinforcing its authority and influence throughout the medieval period.

Conclusion

Augustine’s theological and philosophical contributions have had an enduring impact on Western Christianity. His ideas on original sin, grace, free will, and the nature of the Church shaped medieval scholasticism and influenced key figures such as Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, and John Calvin. His works, particularly Confessions and The City of God, remain foundational texts in both theology and philosophy.

However, Augustine’s legacy is not without controversy. His doctrines of predestination and eternal punishment have been criticized for their implications about divine justice and human freedom. Additionally, his antisemitic views and institutional emphasis on the Church have been reevaluated in light of modern ethical and theological concerns.

Despite these debates, Augustine’s intellectual depth and spiritual insight make him one of the most significant architects of Christian theology. His synthesis of faith and reason bridged the ancient Greco-Roman world with the emerging medieval Christian tradition, shaping the trajectory of Western thought for centuries to come – whether seen as a blessing or a curse.

References and further reading

- Brown, P., Augustine of Hippo: A Biography, 2013, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520280410

- Chadwick, H., Augustine: A Very Short Introduction, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192854520

- Markus, R.A., The End of Ancient Christianity, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521339490

- Rist, J.M., Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521589529

- Dodaro, R., Christ and the Just Society in the Thought of Augustine, 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521841627

- Pelikan, J., The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), 1975, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226653716

- Augustine, Confessions, translated by H. Chadwick, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0241295793

- Augustine, The City of God, translated by R.W. Dyson, 1998, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521468435

- Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, translated by D.W. Robertson, 1958, Pearson, ISBN: 978-0024021502

- Augustine, De Trinitate (On the Trinity), translated by O. S. A John E. Rotelle, 2012, New City Press, ISBN: 978-1565484467

- Augustine, On Free Choice of the Will, translated by T. Williams, 1993, Hackett Publishing, ISBN: 978-0872201880

- O’Donnell, J.J., Augustine: A New Biography, 2006, Ecco, ISBN: 978-0060535384

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 4 Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

comments