Origen of Alexandria: Elevating Christianity from a mystery-cult to systematic theology

Origen of Alexandria stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of early Christianity. Living in a time of intense intellectual and religious ferment, he sought to elevate Christianity from its origins as a Jewish mystery-cult to a coherent and systematic theology capable of engaging with the sophisticated philosophical traditions of the Greco-Roman world. Through his synthesis of Christian doctrine and Greek philosophy, Origen laid the groundwork for a rational theology that would shape the intellectual trajectory of Christianity for centuries. In this post, we examine Origen’s life, his theological innovations, and his legacy within the framework of Christian and ancient philosophical thought.

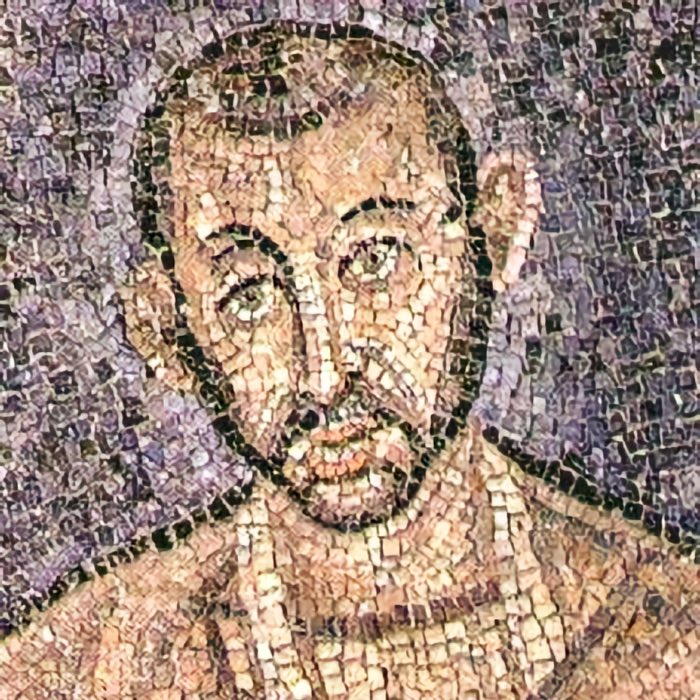

Origen of Alexandria as depicted c. 1160. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Origen’s life and context

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185–c. 253 CE) was a pioneering thinker in early Christianity, whose life and work embodied the dynamic interplay between faith and reason. Born into a Hellenized Jewish-Christian family in Alexandria, a city renowned for its intellectual vibrancy, Origen was immersed in a milieu where Jewish, Christian, and Greco-Roman philosophical traditions intersected. This cultural and religious diversity provided the fertile soil in which his innovative theological ideas took root.

Dutch illustration by Jan Luyken (1700), showing Origen teaching his students. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The early years of Origen’s life were marked by personal loss and profound religious commitment. The martyrdom of his father, Leonides, during the persecution of Christians by Emperor Septimius Severus in 202 CE profoundly shaped Origen’s trajectory. This event likely inspired his lifelong dedication to Christian scholarship. As a young man, Origen immersed himself in the study of Greek philosophers, particularly Plato and the Stoics, as well as Jewish and Christian texts. His education equipped him to engage with the intellectual elite of his time, many of whom regarded Christianity as an unsophisticated belief system. Origen sought to counter this perception by demonstrating that Christian teachings were compatible with, and even superior to, Greek philosophy.

Despite financial and institutional challenges, Origen’s devotion to education and theology led him to establish a catechetical school in Alexandria (a school focused on the instruction of Christian doctrine and faith), where he gained a reputation for rigorous intellectual work and innovative theological inquiry. Over the course of his life, Origen authored numerous works and embarked on extensive travels, including to Palestine and Arabia, to engage with other scholars and religious figures.

His bold theological explorations, however, brought him into conflict with ecclesiastical authorities, culminating in his excommunication from the church in Caesarea. In his later years, Origen faced imprisonment and torture during the Decian persecution, and though he was eventually released, he succumbed to his injuries around 253 CE.

Origen’s synthesis of Christianity and Greek philosophy

Origen’s primary aim was to defend and articulate the faith in terms that would appeal to both Christians and non-Christians. His works, particularly On First Principles (De Principiis) and Contra Celsum, reveal his efforts to integrate Christian theology with Platonic and Stoic thought.

Platonic idealism and the nature of God

Origen, educated in the school of Clement of Alexandria and deeply influenced by his father, was fundamentally a Platonist with occasional traces of Stoicism. His idealistic worldview regarded temporal and material things as insignificant, emphasizing that only eternal realities exist within the realm of Platonic ideas. For Origen, “God” represented the ultimate ideal, the central and pure foundation of existence. This conception aligns closely with Platonic thought about The One as the ineffable, ultimate source of all being. While The One in Platonism is abstract and impersonal, Origen adapted this framework to a biblical, personal God who actively creates and interacts with the world.

Origen’s “God” shares similarities with The One in terms of transcendence and the role as the source of all reality. However, unlike the Platonic One, which emanates existence passively, Origen’s “God” actively and willfully creates. The logos plays a critical intermediary role in this process (see below), mediating between “God” and creation, akin to how Platonic intermediaries (such as the Nous) bridge the gap between The One and the material realm. This synthesis allowed Origen to integrate Greek metaphysical principles with Christian doctrines while preserving the relational and personal nature of the biblical god YHWH.

Moreover, Origen’s emphasis on the insignificance of the material world and the primacy of eternal, spiritual realities is deeply rooted in Platonic idealism. This perspective shaped his theological outlook, particularly his views on salvation, spiritual ascent, and the relationship between God and humanity.

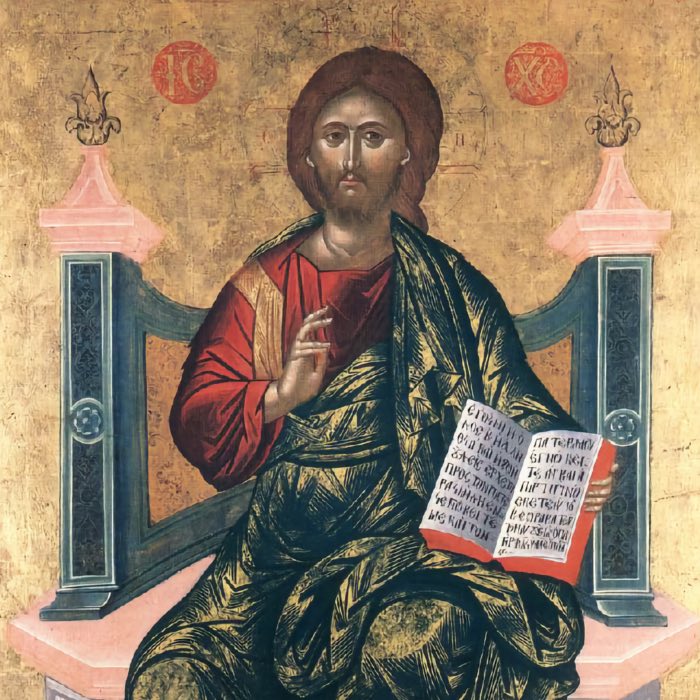

Logos as the mediator

Central to Origen’s thought was the concept of the logos. In classical Greek philosophy, the logos (Greek for “word”) was understood as the rational principle that permeates and orders the universe. For the Stoics, it represented the divine reason inherent in nature, governing all things. In Platonic thought, the logos functioned as an intermediary between the transcendent One and the material world, bridging the gap between ultimate reality and its manifestations.

In the Gospel of John, the logos is linked to Jesus, identifying him as the “divine Word” made flesh. Origin builds upon that notion and understand Jesus not just as the savior of humanity but also the rational principle that orders the cosmos. This allowed Origen to bridge the gap between Greek philosophical ideas about the structure of reality and the Christian belief in Jesus as the divine Son of God.

The logos, in Origen’s thought, is not merely an abstract principle but a dynamic, eternal force permeating the universe as its rational and creative foundation. Drawing from classical philosophy, Origen emphasized that since God eternally manifests Himself, the logos is likewise eternal. It functions as a bridge between creation and the uncreated, providing the medium through which the incomprehensible and incorporeal God makes Himself known to the world.

All creation, Origen argues, comes into existence solely through the logos. God’s first interaction with the world is through this “divine Word”, which is both the manifestation of divine wisdom and the organizing principle of the cosmos. For Origen, the logos stands as God’s visible representative, enabling a transcendent and unknowable God to engage with His creation.

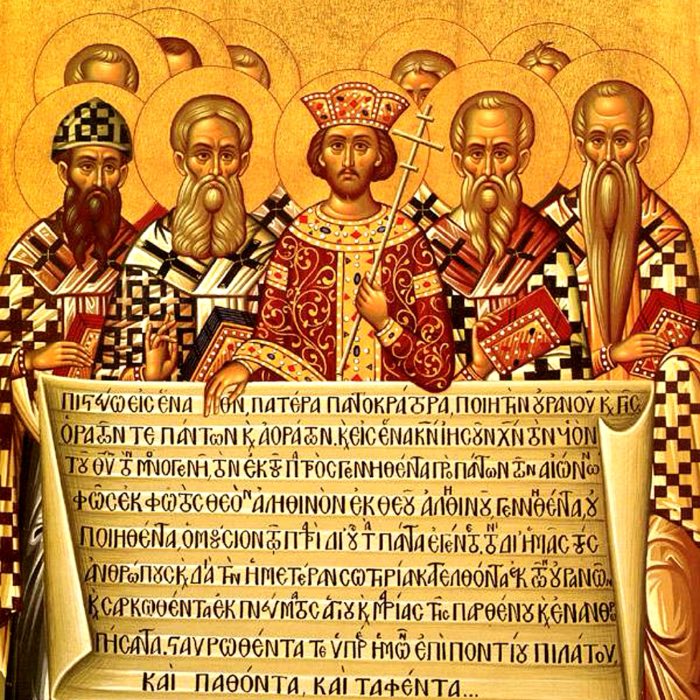

Subordination of the Son and the Logos

Origen’s defense of monotheism and the unity of God against Gnostic interpretations led him to emphasize the subordination of the Son to the Father. The logos, identified with the Son, is distinct in nature from the Father. Origen refrained from using the term “of the same substance as the Father”, later central to Nicene theology, instead describing the logos as a reflection of God’s essence — a lesser divine entity yet the highest among created or derived beings.

Origen’s logos theology also highlights the humanity of Christ. He differentiated between the Father as the “first logos” and the Son as the “second logos”, maintaining that the Father is greater than the Son, an assertion that would later become contentious in theological debates.

The role of humans

In Origen’s theology, created rational beings are reflections of the logos and participate in its divine rationality. Humans, as part of this created order, strive for perfection by turning back to their ultimate cause — “God”. This return to their original state of being is the goal of the cosmic process, and human free will plays a central role in this journey (see below). Despite the overarching divine providence guiding the universe, Origen emphasized the essential role of individual choice in the process of salvation.

For Origen, God designed the universe so that all its components work together toward a unified cosmic purpose. Humanity, as beings “imprinted” with the image of God, achieves this purpose by imitating God. Through the recognition of their own weaknesses and reliance on divine grace, humans can aspire to become like God. This transformation is supported by the logos, which operates through the saints, prophets, and guardian angels to guide humanity.

Sin, in Origen’s understanding, results from a lack of pure knowledge and creates separation from the divine. The restoration of this connection — the return to God/the divine — is at the heart of Origen’s view of human destiny within the grand cosmic order.

The soul and spiritual ascent

Origen held a Platonic belief that the soul, though capable of recognizing God as the ultimate foundation, was imprisoned within the body in this temporal world. Upon death, he taught, the soul would ascend to the divine realm, ascending purified of all shadows of evil through fire – the purgatory. This purification was essential for reuniting the soul with its divine origin, knowing the truth of the divine as Jesus knew it, reflecting Origen’s fusion of Platonic metaphysics with Christian soteriology.

His idea of purgatory largely corresponded to the Platonic concept that the world would be purified by a fire of evil and thus lead to cosmic renewal. Through further spiritualization, Origen was able to name God himself as this consuming fire. In proportion as souls were freed from sin and ignorance, the material world would be transcended until, after infinite eons, at the eventual end, God would be all in all and the worlds and spirits would return to the knowledge of God. Origen did not know of eternal punishments, as they occur in the later prevailing idea of hell (see below).

Gnostic influence and exegetical methods

In his attempt to reconcile Greek thought with Christian teachings, Origen was influenced by the Platonizing Philo of Alexandria and elements of Gnosticism. However, he avoided the extremes of Gnostic interpretations by anchoring his work in the New Testament canon and Church ritual tradition. Despite this, Gnostic and Hellenistic ideas pervaded his writings, including the tripartite division of humanity into body (soma), soul (psyche), and spirit (nous). Origen extended this schema to scripture itself, asserting that the Bible could be understood on three levels: literal, moral, and mystical (see below).

Preexistence of the soul

Origen’s theology was deeply influenced by Platonic metaphysics, particularly the idea of the soul’s preexistence. He argued that all souls were created by God in a state of equality and freedom. However, through misuse of their free will, souls fell from their original unity with God, resulting in their embodiment in the material world.

This concept provided a framework for understanding human suffering and the role of Christian teachings in guiding souls back to their divine origin. For Origen, salvation was not a one-time event but a process of spiritual ascent requiring moral purification and the cultivation of wisdom.

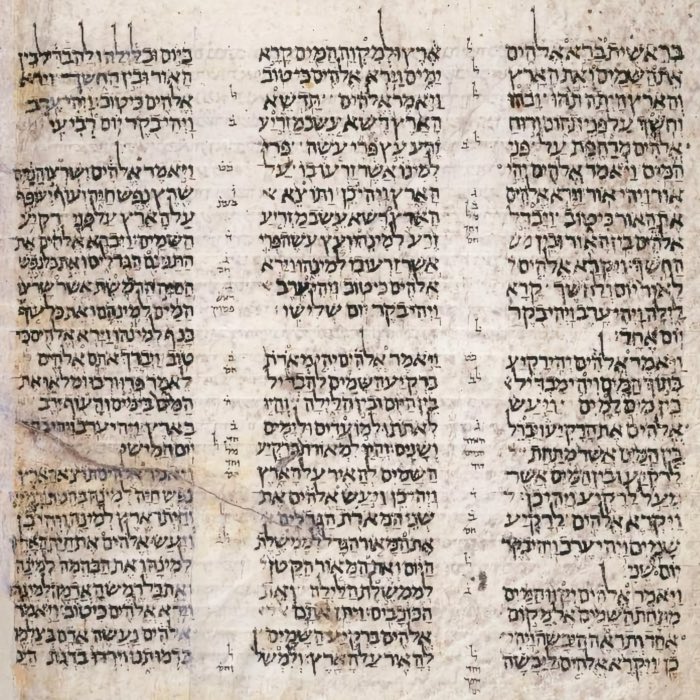

Allegorical interpretation and the unity of scripture

Origen’s commitment to scripture was unparalleled. He viewed the Bible as an organic whole, unified by the divine logos. Rejecting Marcionite claims of the Old Testament’s inferiority, Origen saw apparent contradictions between the Testaments as superficial, arising from overly literal interpretations. His allegorical approach sought to uncover the spiritual meaning underlying the text, using methods like name translations to reveal deeper truths, while also insisting on rigorous grammatical analysis.

Origen’s approach to scripture was heavily influenced by Greek philosophical traditions of allegorical interpretation. Drawing on the methods of Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher, Origen argued that the Bible contained multiple levels of meaning:

- Literal: The surface narrative of scripture.

- Moral: Ethical lessons applicable to daily life.

- Spiritual/allegorical: Deeper truths about God and the soul’s journey.

For Origen, the spiritual meaning of scripture was the most important, as it revealed the eternal truths underlying the historical events. This approach allowed him to harmonize apparent contradictions in the Bible and align its teachings with Greek philosophical concepts.

The visible and invisible Church

Origen drew a clear distinction between the visible and invisible Church, influenced by Platonic dualism. The visible Church, composed of humans, served as a refuge for sinners, while the invisible Church, a heavenly ideal, represented the true Church of Christ. This dual Church reflected Origen’s belief in the ultimate transcendence and permanence of spiritual truths over earthly institutions.

The spiritual elite in Origen’s exegesis

Another Platonic notion central to Origen’s thought was the division between the masses, who were only capable of understanding scripture literally, and a minority capable of grasping its deeper, hidden meanings. For Origen, the organized Church was transient, while its spiritual message endured eternally.

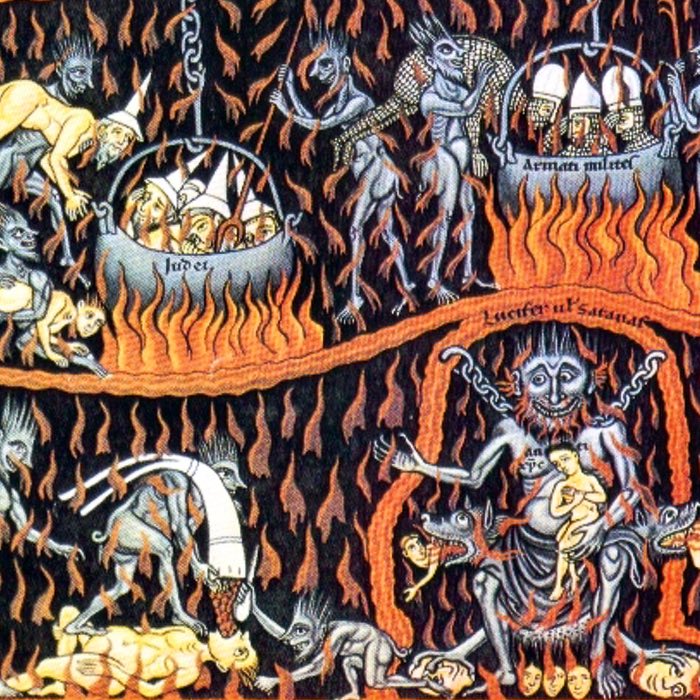

Universal salvation

One of Origen’s most controversial ideas was the doctrine of apokatastasis, or universal restoration. He believed that, ultimately, all beings — including the devil and fallen angels — would be reconciled to God. He backed this up with 1 Cor 15:28:

When all things have been subjected to him, he, the Son, will also subject himself to him who subjected all things to him, so that God may rule over all and in all things.

This belief was rooted in his understanding of God’s infinite love and justice, as well as the Platonic principle that evil is a temporary aberration rather than an eternal reality.

Origen’s vision of universal salvation stood in contrast to the more rigid dichotomy of eternal heaven and hell that characterized later Christian theology. While his view was later condemned as heretical, it reflects his optimistic belief in the transformative power of divine love.

Free will and theodicy

Origen placed significant emphasis on human free will, a theme that resonated with both Stoic and Platonic traditions. He argued that God created rational beings with the ability to choose between good and evil, making them morally responsible for their actions.

This belief in free will also informed Origen’s response to the problem of evil. He maintained that suffering and sin were the result of human choices rather than divine intention. God permitted evil as part of a larger plan to guide souls toward repentance and spiritual growth, a process exemplified in Christian teachings on forgiveness and transformation.

Theological foundations

Origen’s theological innovations laid the groundwork for several key doctrines that would shape the development of Christian thought:

- Trinity: Origen articulated an early understanding of the Trinity, emphasizing the distinction between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit while maintaining their unity. He described the Son as eternally begotten of the Father, using Platonic concepts of emanation to explain their relationship.

- Christology: For Origen, Jesus was both fully divine and fully human, serving as the bridge between God and humanity. His incarnation was an expression of divine love, enabling humans to ascend toward their original state of unity with God.

- Spiritual ascent: Origen emphasized the soul’s journey toward God through stages of purification, illumination, and union. This process required intellectual and moral discipline, reflecting both Platonic and Christian ideals.

- Mysticism and contemplation: Origen viewed mystical contemplation as the highest form of worship. By transcending the material world and focusing on the divine, believers could experience a direct encounter with God.

Legacy

Christianity, in its mainstream perception, is often reduced to a simplistic narrative — a “goody-goody” story of miracles, moralistic teachings, and the promise of salvation through faith and adherence to the Church. This view, while widespread, neglects the profound intellectual and theological foundations upon which Christianity was built, in my opinion. What appears to some as a primitive religious cult is, in reality, rooted in centuries of philosophical and theological development, much of which owes its depth to Origen of Alexandria.

Origen’s synthesis of Greek philosophy with Christian revelation introduced concepts of rationality and universal order into Christian theology. His work elevated Christianity from its origins as a mystery-cult to a sophisticated framework capable of engaging the intellectual elite of the Greco-Roman world. Ideas such as the transformative power of the logos, the role of free will, and the cosmic return to divine unity form the hidden scaffolding upon which much of Christian thought rests, even if these ideas are not consciously recognized today.

Yet, over time, the influence of figures like Origen became obscured by the institutionalization of Christianity. Simplified teachings and mythological narratives often overshadowed the rich philosophical underpinnings of early theological thought. Despite this, Origen’s intellectual contributions continue to resonate in the broader framework of Christian theology. His legacy is present in the rational structures of faith, even when hidden beneath layers of doctrinal tradition.

Conclusion

Origen’s integration of Christian theology with Greek philosophy had a profound and lasting impact on Christian thought. His works influenced major figures such as Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine of Hippo, and Thomas Aquinas, and his allegorical approach to scripture became a cornerstone of medieval exegesis. However, some of his ideas, particularly apokatastasis and the preexistence of souls, were later deemed heretical by the Church. These theological debates highlight the dynamic process through which orthodoxy was defined in early Christianity.

Despite these controversies, Origen’s efforts to harmonize faith and reason expanded the appeal of Christian and laid the groundwork for much of its theological tradition. His vision of a rational, compassionate, and transformative faith underscores the depth and adaptability of early Christian thought.

As such, I think Origen can be regarded as the second founder of Christian theology, following Paul. While Paul fortified and further conceptualized the idea of a celestial savior called “Jesus”, who was later historized, Origen built upon this framework, embedding Christian doctrine within the intellectual traditions of the Greco-Roman world. By systematically synthesizing Platonic metaphysics, Stoic ethics, and Christian revelation, Origen gave Christianity a philosophical depth that allowed it to engage with the educated classes of the Roman Empire. This intellectual rigor not only legitimized the faith in the eyes of pagan philosophers but also provided the emerging Church with a theological framework that would shape its doctrines for centuries.

Origen’s contributions extend far beyond his immediate historical context. His allegorical interpretation of scripture, his emphasis on free will, and his vision of universal salvation continue to resonate in contemporary theological discussions. While later orthodoxy rejected some of his more speculative ideas, many of his concepts — such as the transformative power of the logos and the unity of God’s plan for creation — remain integral to Christian theology.

While in today’s perception Origen is perhaps not prominently recognized, Christian theology is imbued with his ideas, whether consciously acknowledged or not. His intellectual daring and spiritual depth make him a pivotal figure in the development of Christianity, bridging the gap between its Jewish origins and its role as a universal faith grounded in reason and compassion.

References and further reading

- McGuckin, J.A., Origen of Alexandria: Master Theologian of the Early Church, 2024, Globe Pequot Publishing Group Inc/Bloomsbury, ISBN: 978-1978708457

- Trigg, J.W., Origen: The Bible and philosophy in the third-century church, 2012, SCM Press, ISBN: 978-0334022343

- Crouzel, H., Origen, 1999, T&T Clark, ISBN: 978-0567086396

- Heine, R.E., Origen: Scholarship in the service of the church, 2011, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199209088

- Kannengiesser, C., Handbook of Patristic Exegesis: The Bible in Ancient Christianity, 2006, Brill, ISBN: 978-9004153615

- Martens, P.W., Origen and Scripture: The contours of the exegetical life, 2012, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199639557

- Grant, R.M., Greek Apologists of the Second Century, 2012, SCM Press, ISBN: 978-0334005353

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, 2010, Book, Penguin, ISBN: 9781101189993

- Chadwick, H., The early church, 1993, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0140231991

- Origen, On First Principles (De Principiis), 2013, Christian Classics, ISBN: 978-0870612794

- Origen, Contra Celsum, 2008, Cambridge University Press, translated by H. Chadwick, ISBN: 978-0521295765

- Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, 2011, Catholic University of America Press, ISBN: 978-1108029568

comments