Nida: A glimpse into Roman provincial life

During a recent visit to the Frankfurt, I had the opportunity to explore the Archäologisches Museum Frankfurtꜛ and its impressive collection of artifacts from the Roman city of Nida. As I wandered through the museum’s galleries, I was struck by the tangible connection to the Roman past that Nida represented. This vicus, located in the modern Frankfurt-Heddernheim district, offered an intricate view of daily life, trade, and cultural exchange within the Roman province of Germania Superior. The museum’s exhibits, ranging from pottery and coins to architectural fragments and religious artifacts, provided an immersive experience of a settlement that, though often overshadowed by larger Roman cities, played a significant role in the region’s development. In this post, I’d like to share some insights into the historical and archaeological significance of Nida, along with some photos from my visit to the museum.

The archaeological museum of Frankfurt is located in the heart of the city and houses a rich collection of artifacts from the Roman settlement of Nida. The exhibits offer a glimpse into the daily life, culture, and economy of this ancient vicus. The museum itself is housed in a former Carmelite monastery, adding to its historical ambiance.

The archaeological museum of Frankfurt is located in the heart of the city and houses a rich collection of artifacts from the Roman settlement of Nida. The exhibits offer a glimpse into the daily life, culture, and economy of this ancient vicus. The museum itself is housed in a former Carmelite monastery, adding to its historical ambiance.

The historical and geographical context of Nida

Nida’s history is inseparable from its strategic location near the Limes Germanicus, the fortified frontier of the Roman Empire. Situated in the fertile Rhine-Main region, the vicus, a Roman civilian settlement, acted as a hub for trade, military logistics, and cultural exchange. Its proximity to the Main River facilitated transportation and commerce, allowing goods and ideas to flow between Germania Superior and other parts of the empire.

Map of the Roman province of Germania. Nida is located in the center, East of Mogontiacum (Mainz). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Established during the 1st century CE, Nida evolved as a civilian settlement closely associated with the Roman military presence in the area. The fortifications along the Limes were designed to protect Roman territory and manage interactions with the Germanic tribes. Nida, though not a military base itself, thrived under the protection and economic stimulation provided by the nearby troops.

Aerial view of Nordweststadt around 1970, with the course of the city wall of the former Roman vicus Nida marked in red. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt

Aerial view of Nordweststadt around 1970, with the course of the city wall of the former Roman vicus Nida marked in red. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt

Urban structure and daily life in Nida

Archaeological evidence paints a picture of a well-organized settlement with a grid layout — a hallmark of Roman urban planning. The town featured distinct zones for administration, trade, and residential life. The forum likely served as the central hub, surrounded by administrative buildings, markets, and temples. Streets were paved and flanked by stone and timber-framed buildings, reflecting a blend of Roman architectural styles and local adaptations.

Map of Roman fortifications (in red) and civilian settlements (blue) in Nida-Heddernheim. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Public amenities such as bathhouses (thermae) underscored the Roman emphasis on hygiene and social interaction. These facilities were more than places for bathing; they served as venues for relaxation, networking, and even conducting business. The remains of these structures, alongside the intricate mosaics and hypocaust heating systems discovered at the site, provide insights into the technological sophistication of the time.

Residential areas reveal a diverse population comprising merchants, artisans, and possibly Romanized locals. Excavations have unearthed household items such as pottery, tools, and jewelry, offering glimpses into the daily routines and material culture of Nida’s inhabitants. The presence of imported goods — ranging from fine ceramics to exotic spices — points to the settlement’s integration into broader trade networks.

Economic and cultural significance

Nida’s economy was vibrant, driven by local craftsmanship and trade. Artisans produced pottery, tools, and metalwork, which were traded locally and beyond. Coins minted in the region indicate economic stability and connectivity with the wider Roman world. The settlement’s location along key trade routes allowed it to serve as a distribution center for goods moving between the frontier and the interior of the empire.

Culturally, Nida reflected the complex interplay between Roman and local traditions. Religious practices, for instance, showcased a synthesis of Roman and indigenous beliefs. Temples and altars dedicated to deities like Jupiter, Mercury, and Mithras were found alongside evidence of native cults. The discovery of a Mithraeum (a temple dedicated to Mithras) highlights the spread of mystery religions in the Roman provinces, appealing to diverse groups within the population. Also evidence of early Christian presence in the region has been found, indicating the gradual spread of Christianity in the Roman provinces North of the Alps.

Mercury, sandstone, 3rd century CE. Mercury was the god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence, messages, communication, travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves. He also served as the guide of souls to the underworld. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Mercury, sandstone, 3rd century CE. Mercury was the god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence, messages, communication, travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves. He also served as the guide of souls to the underworld. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Minerva, sandstone 3rd century CE. Minerwa was the goddess of wisdom, war, art, schools, and commerce. She was the Roman counterpart of the Greek goddess Athena. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Minerva, sandstone 3rd century CE. Minerwa was the goddess of wisdom, war, art, schools, and commerce. She was the Roman counterpart of the Greek goddess Athena. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Epona, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Epona was a protector of horses, donkeys and mules. She was also the goddess of fertility, healing, and the protector of travelers. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Epona, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Epona was a protector of horses, donkeys and mules. She was also the goddess of fertility, healing, and the protector of travelers. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Rock birth of Mithras, sandstone, 3rd century CE.Mithras was a deity of Persian origin who became popular in the Roman Empire. His cult, known as Mithraism, was a mystery religion that involved secret rituals and initiation ceremonies. The scene depicted here, known as the “Rock Birth of Mithras”, is a central motif in Mithraic iconography, symbolizing the god’s emergence from a rock, signifying the birth of a new cosmic order. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Rock birth of Mithras, sandstone, 3rd century CE.Mithras was a deity of Persian origin who became popular in the Roman Empire. His cult, known as Mithraism, was a mystery religion that involved secret rituals and initiation ceremonies. The scene depicted here, known as the “Rock Birth of Mithras”, is a central motif in Mithraic iconography, symbolizing the god’s emergence from a rock, signifying the birth of a new cosmic order. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Votive stone for Silvanus, sandstone, vicus area. Silvanus, the god of vegetation, holds a tree knife in his right hand. He has placed a bundle of cut branches over his shoulder to feed his cattle. He stands in a stylized sanctuary with his tunic on. The god protected all rural property, especially the animals. Soldiers and traders worshipped him, as did woodcutters and hunters. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Votive stone for Silvanus, sandstone, vicus area. Silvanus, the god of vegetation, holds a tree knife in his right hand. He has placed a bundle of cut branches over his shoulder to feed his cattle. He stands in a stylized sanctuary with his tunic on. The god protected all rural property, especially the animals. Soldiers and traders worshipped him, as did woodcutters and hunters. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Silver votive plate without inscription, replica. Rectangular in the shape of a ‘tabula ansata’. Side handles cut off. Two rivet holes at the top and bottom. Jupiter stands in the center, clad only in his cloak, which hangs from his left shoulder. He holds the sceptre in his raised left hand and the thunderbolt in his right. In front of him on the ground stands an eagle on a globe, holding a wreath in its beak and looking up at the god. At the four corners of the aedicula are small medallions depicting the winged Cupid with a lance and round shield.

Silver votive plate without inscription, replica. Rectangular in the shape of a ‘tabula ansata’. Side handles cut off. Two rivet holes at the top and bottom. Jupiter stands in the center, clad only in his cloak, which hangs from his left shoulder. He holds the sceptre in his raised left hand and the thunderbolt in his right. In front of him on the ground stands an eagle on a globe, holding a wreath in its beak and looking up at the god. At the four corners of the aedicula are small medallions depicting the winged Cupid with a lance and round shield.

Silver votive plate with Jupiter in Roman garb and inscription, replica. Above the pediment of the aedicula three diverging, decorated points, which can be interpreted as stylized palm leaves. Inscription:I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)DOLICHIINO VBI FIRRVM NASCITVR FLAVIVS FIDIILISIT Q(uintus) IVLIVS POSSTIM VS IIX IMPIRIO IPSIVS PRO SITT SVOSTranslation: To the best and greatest Jupiter. Dolichenus (from the land) where iron comes from, Flavius Fidelis and Quintus Julius Postumus consecrated the silver plate for themselves and theirs by order (of the god).

Silver votive plate with Jupiter in Roman garb and inscription, replica. Above the pediment of the aedicula three diverging, decorated points, which can be interpreted as stylized palm leaves. Inscription:I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)DOLICHIINO VBI FIRRVM NASCITVR FLAVIVS FIDIILISIT Q(uintus) IVLIVS POSSTIM VS IIX IMPIRIO IPSIVS PRO SITT SVOSTranslation: To the best and greatest Jupiter. Dolichenus (from the land) where iron comes from, Flavius Fidelis and Quintus Julius Postumus consecrated the silver plate for themselves and theirs by order (of the god).

Bronze plate decorated in relief in a triangular shape with an arrowhead-like finial, 2nd century to 1st half of the 3rd century CE. Plates of this type were votive offerings, but were also carried in processions with the help of carrying poles. In the center of the relief, Jupiter Dolichenus is depicted standing on the bull; he holds the double axe in his right hand and the six-pointed bundle of lightning in his left. He is dressed in Phrygian pants and cap and Roman armor. A large sword hangs down behind him from a sword strap (balteus). Above the god hovers Victoria with a wreath and palm frond, above which is the bust of the sun god Sol. In the center of the lower field, Juno Dolichena stands on a hind with the scepter in her left hand and the cult rattle (sistrum) in her right. She wears the crown of Isis. The goddess is flanked by giants with legs curled up like volutes; they carry three-leafed branches in their raised hands. The busts of Luna and Sol can be seen above the heads of the giants.

Bronze plate decorated in relief in a triangular shape with an arrowhead-like finial, 2nd century to 1st half of the 3rd century CE. Plates of this type were votive offerings, but were also carried in processions with the help of carrying poles. In the center of the relief, Jupiter Dolichenus is depicted standing on the bull; he holds the double axe in his right hand and the six-pointed bundle of lightning in his left. He is dressed in Phrygian pants and cap and Roman armor. A large sword hangs down behind him from a sword strap (balteus). Above the god hovers Victoria with a wreath and palm frond, above which is the bust of the sun god Sol. In the center of the lower field, Juno Dolichena stands on a hind with the scepter in her left hand and the cult rattle (sistrum) in her right. She wears the crown of Isis. The goddess is flanked by giants with legs curled up like volutes; they carry three-leafed branches in their raised hands. The busts of Luna and Sol can be seen above the heads of the giants.

Fragmentary Jupiter column, sandstone, basalt (Jupiter), 1st half of the 3rd century CE. One of two complete Jupiter columns recovered in 2003 in the center of Nida. The imposing votive monuments dedicated to the highest Roman god were dismantled by the Roman population after the middle of the 3rd century and carefully deposited in a specially excavated pit. Similar deposits in wells and cisterns are documented several times in Nida. Obviously, when the town was abandoned, cult monuments were officially desecrated, laid down and concealed in order to prevent them from being seized by advancing Germanic tribes. The inscription reads:I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)ET IN NONIREGINAE – Jupiter, the best and greatest, and Juno, the queen.

Fragmentary Jupiter column, sandstone, basalt (Jupiter), 1st half of the 3rd century CE. One of two complete Jupiter columns recovered in 2003 in the center of Nida. The imposing votive monuments dedicated to the highest Roman god were dismantled by the Roman population after the middle of the 3rd century and carefully deposited in a specially excavated pit. Similar deposits in wells and cisterns are documented several times in Nida. Obviously, when the town was abandoned, cult monuments were officially desecrated, laid down and concealed in order to prevent them from being seized by advancing Germanic tribes. The inscription reads:I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)ET IN NONIREGINAE – Jupiter, the best and greatest, and Juno, the queen.

Jupiter columns: The towering, decorated columns with a base, ‘four gods stone’, ‘week gods stone’ and capital, crowned by a Jupiter on horseback or the enthroned gods Jupiter and Juno are among the most striking monuments of the Roman period north of the Alps. The motif of the leaf-wreathed Jupiter column originates from Italy. Alone as an enthroned god, together with Juno, his wife or as the conqueror of a giant on horseback - the votive sculpture is always dedicated to the highest Roman deity. However, the concentration of these votive stones in Gaul and the border provinces on the Rhine, as well as divine attributes such as the wheel, suggest that the monuments were reshaped by the local population according to Celtic beliefs. Jupiter takes on the form of a heavenly lord on horseback who conquers evil. The depictions of Minerva, Mercury, Apollo and Hercules on the ‘Stone of the Four Gods’ have a Roman character. However, these reliefs can also reflect comparable fields of activity of native deities such as economic success, fertility and health. The gods of the week (Saturn, Sol, Luna, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter and Venus) symbolized striving and the orderly passage of time. The wealthy upper classes in Nida entrusted themselves to the benevolence of the gods, especially in the 3rd century with the representative monuments. This took place at a time of profound internal crisis and external threat to the Roman Empire. The followers of the cult probably hid the sacred columns in wells and specially dug pits when the city was abandoned after the middle of the 3rd century. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jupiter columns: The towering, decorated columns with a base, ‘four gods stone’, ‘week gods stone’ and capital, crowned by a Jupiter on horseback or the enthroned gods Jupiter and Juno are among the most striking monuments of the Roman period north of the Alps. The motif of the leaf-wreathed Jupiter column originates from Italy. Alone as an enthroned god, together with Juno, his wife or as the conqueror of a giant on horseback - the votive sculpture is always dedicated to the highest Roman deity. However, the concentration of these votive stones in Gaul and the border provinces on the Rhine, as well as divine attributes such as the wheel, suggest that the monuments were reshaped by the local population according to Celtic beliefs. Jupiter takes on the form of a heavenly lord on horseback who conquers evil. The depictions of Minerva, Mercury, Apollo and Hercules on the ‘Stone of the Four Gods’ have a Roman character. However, these reliefs can also reflect comparable fields of activity of native deities such as economic success, fertility and health. The gods of the week (Saturn, Sol, Luna, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter and Venus) symbolized striving and the orderly passage of time. The wealthy upper classes in Nida entrusted themselves to the benevolence of the gods, especially in the 3rd century with the representative monuments. This took place at a time of profound internal crisis and external threat to the Roman Empire. The followers of the cult probably hid the sacred columns in wells and specially dug pits when the city was abandoned after the middle of the 3rd century. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jupiter’s sowle, sandstone, north of the vicus, east of the Roman road to Saalburg, 239 CE. The four-god stone shows an inscription and the gods Apollo, Minerva and Hercules. The gods of the week were depicted in seven niches on the round pedestal. The lower bodies of the enthroned gods Jupiter and Juno, the right upper body of Juno and the canopy with the heads were preserved.The inscription reads: (I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo))(et Ivn) O(ni)(Regi) NAE(Vic)TORIN(us)(de)C(urio) C(ivitatis) AVDE(r(iensium))IN SVO (ex voto a(nte) d(iem))VII ID(us) (no)VE(mbres)(iMP(e) (ratore) D(omino) N(ostro) (M(arco)Ant(onio))Gordi(ano)AUG(usto) ET AV(iola)CO(n)S(ulibus) – Jupiter, the best and greatest, and Juno, the royal, (has) … (?) … Victorinus, councillor of the Civitas Auderiensium, on the basis of a vow (the pillar) on his own property on the 7th day before the Ides of November, when Emperor Marcus Antonius Gordianus and Aviola were consuls (= November 7 239 CE), (consecrated). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jupiter’s sowle, sandstone, north of the vicus, east of the Roman road to Saalburg, 239 CE. The four-god stone shows an inscription and the gods Apollo, Minerva and Hercules. The gods of the week were depicted in seven niches on the round pedestal. The lower bodies of the enthroned gods Jupiter and Juno, the right upper body of Juno and the canopy with the heads were preserved.The inscription reads: (I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo))(et Ivn) O(ni)(Regi) NAE(Vic)TORIN(us)(de)C(urio) C(ivitatis) AVDE(r(iensium))IN SVO (ex voto a(nte) d(iem))VII ID(us) (no)VE(mbres)(iMP(e) (ratore) D(omino) N(ostro) (M(arco)Ant(onio))Gordi(ano)AUG(usto) ET AV(iola)CO(n)S(ulibus) – Jupiter, the best and greatest, and Juno, the royal, (has) … (?) … Victorinus, councillor of the Civitas Auderiensium, on the basis of a vow (the pillar) on his own property on the 7th day before the Ides of November, when Emperor Marcus Antonius Gordianus and Aviola were consuls (= November 7 239 CE), (consecrated). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Four-gods stone, part of a lost Jupiter column, sandstone, 240 CE; version with lime application, red and yellow color pigments to emphasize the depiction are proven. Center of the vicus, from a pit, excavated in 2001. Hercules, Minerva and Mercury can be seen next to the inscription. The inscription reads: (I(ovi)) O(ptimo) (M(aximo))IVNONI REGIN(a)E IVLIVSEVTICH(ia)NVS VE(t(eranus))IN (s)VO (pos(uit))L(ibens) L(aetus) M(erito) DED(ic(avit))CAL(endis) IV(n(ias) Sa)BINO II (et) VENVSTO C(o(n)s(ulibus)) – To Jupiter, the best and greatest, (and) Juno, the royal, Julius Eutichianus, veteran, has erected (the monument) on his property gladly, joyfully and according to due. Dedicated on the calends of June, when Sabinus was consul for the second time and Venustus was consul (= June 1, 240 CE). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Four-gods stone, part of a lost Jupiter column, sandstone, 240 CE; version with lime application, red and yellow color pigments to emphasize the depiction are proven. Center of the vicus, from a pit, excavated in 2001. Hercules, Minerva and Mercury can be seen next to the inscription. The inscription reads: (I(ovi)) O(ptimo) (M(aximo))IVNONI REGIN(a)E IVLIVSEVTICH(ia)NVS VE(t(eranus))IN (s)VO (pos(uit))L(ibens) L(aetus) M(erito) DED(ic(avit))CAL(endis) IV(n(ias) Sa)BINO II (et) VENVSTO C(o(n)s(ulibus)) – To Jupiter, the best and greatest, (and) Juno, the royal, Julius Eutichianus, veteran, has erected (the monument) on his property gladly, joyfully and according to due. Dedicated on the calends of June, when Sabinus was consul for the second time and Venustus was consul (= June 1, 240 CE). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Parts of a Jupiter column, column drum and capital made of sandstone with remnants of white paint, eastern part of the vicus; from a well in the grounds of the stone fort, 1st half of the 3rd century CE; Giant rider made of limestone; 2nd century CE The Corinthian capital with the heads of the four seasons has been slightly added. Of the crowning group, the head and upper body of the giant, the horse without legs and the torso of Jupiter as a rider in Roman officer’s outfit were preserved. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Parts of a Jupiter column, column drum and capital made of sandstone with remnants of white paint, eastern part of the vicus; from a well in the grounds of the stone fort, 1st half of the 3rd century CE; Giant rider made of limestone; 2nd century CE The Corinthian capital with the heads of the four seasons has been slightly added. Of the crowning group, the head and upper body of the giant, the horse without legs and the torso of Jupiter as a rider in Roman officer’s outfit were preserved. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jupiter’s Column, sandstone, 228 CE, center of the vicus, from a well, excavated together with the parts of another Jupiter’s Column and an altar to Jupiter in 2003. Juno, Minerva, Hercules and Mercury are depicted on the four-god stone. The pedestal in between bears an inscription; the gods of the week can be seen in niches next to it. The coronation group with Jupiter and a tongued giant on the Corinthian capital is damaged, the heads of the god and the Plerdes are missing. The inscription reads: I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)ET IVNONIREGINAE M(arcus) SEVERIVS SEQVE(n)S D(ecurio)C(ivitatis) T(aunensium) V(otum)S(olvit) L(ibens) L(aetus)M(erito)MODESTO (II) ET PR BO CO(n)S(ulibus) – Marcus Severius Segnens, councillor of the Civitas Taunensium, gladly, joyfully and duly fulfilled his vow to Jupiter, the best and greatest, and Juno, the royal, when Modestus (for the second time) and Probus were consuls (= 228 CE). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jupiter’s Column, sandstone, 228 CE, center of the vicus, from a well, excavated together with the parts of another Jupiter’s Column and an altar to Jupiter in 2003. Juno, Minerva, Hercules and Mercury are depicted on the four-god stone. The pedestal in between bears an inscription; the gods of the week can be seen in niches next to it. The coronation group with Jupiter and a tongued giant on the Corinthian capital is damaged, the heads of the god and the Plerdes are missing. The inscription reads: I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)ET IVNONIREGINAE M(arcus) SEVERIVS SEQVE(n)S D(ecurio)C(ivitatis) T(aunensium) V(otum)S(olvit) L(ibens) L(aetus)M(erito)MODESTO (II) ET PR BO CO(n)S(ulibus) – Marcus Severius Segnens, councillor of the Civitas Taunensium, gladly, joyfully and duly fulfilled his vow to Jupiter, the best and greatest, and Juno, the royal, when Modestus (for the second time) and Probus were consuls (= 228 CE). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the Jupiter column above. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the Jupiter column above. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the Jupiter column above. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the Jupiter column above. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the Jupiter column above. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the Jupiter column above. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jupiter column, sandstone, 1st half of the 3rd century CE, center of the vicus, from a fountain. Jupiter enthroned on a Tuscan column: the right arm with lightning rests in the god’s lap, the raised left hand holds the sceptre (both lost). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jupiter column, sandstone, 1st half of the 3rd century CE, center of the vicus, from a fountain. Jupiter enthroned on a Tuscan column: the right arm with lightning rests in the god’s lap, the raised left hand holds the sceptre (both lost). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Archaeological discoveries and interpretations

Excavations at Nida have yielded a wealth of artifacts that illuminate its history and cultural dynamics. The discovery of burial grounds, for example, provides insights into social hierarchies, burial customs, and the health of the population. Grave goods, ranging from weapons to ornamental items, reflect both the wealth and cultural affiliations of the deceased. And just recently, a Christian amulet was discovered, which has sparked new discussions about the timeline of Christianity’s presence in the Roman provinces North of the Alps.

The Mithraeum, one of the most intriguing finds, reveals the spiritual life of Nida’s residents. This underground sanctuary, with its intricate carvings and altars, was a site of initiation and worship, emphasizing the community’s engagement with Roman religious trends.

Everyday life: Impressions from the museum

The artifacts on display at the Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt offer a vivid portrayal of daily life in Nida. From pottery and jewelry to inscriptions and architectural fragments, each object tells a story of the settlement’s inhabitants and their interactions with the wider Roman world. The museum’s collection provides a tangible link to the past, inviting visitors to explore the complexities of Roman life in a frontier settlement.

Pond relief, sandstone. In the center stands Vulcan, the god of fire and the forge, swinging a hammer over an anvil. To his left, Mercury, responsible for flourishing trade, holds up a full purse. On the other side, Minerva, the goddess of arts and crafts, can be seen leaning on her shield. Above this group are the seven gods of the week (Saturn, Sol, Luna, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus), symbolizing the orderly passage of time and activity. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Pond relief, sandstone. In the center stands Vulcan, the god of fire and the forge, swinging a hammer over an anvil. To his left, Mercury, responsible for flourishing trade, holds up a full purse. On the other side, Minerva, the goddess of arts and crafts, can be seen leaning on her shield. Above this group are the seven gods of the week (Saturn, Sol, Luna, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus), symbolizing the orderly passage of time and activity. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Statue of a Roman god (?). Unfortunatly the description was missing. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Statue of a Roman god (?). Unfortunatly the description was missing. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

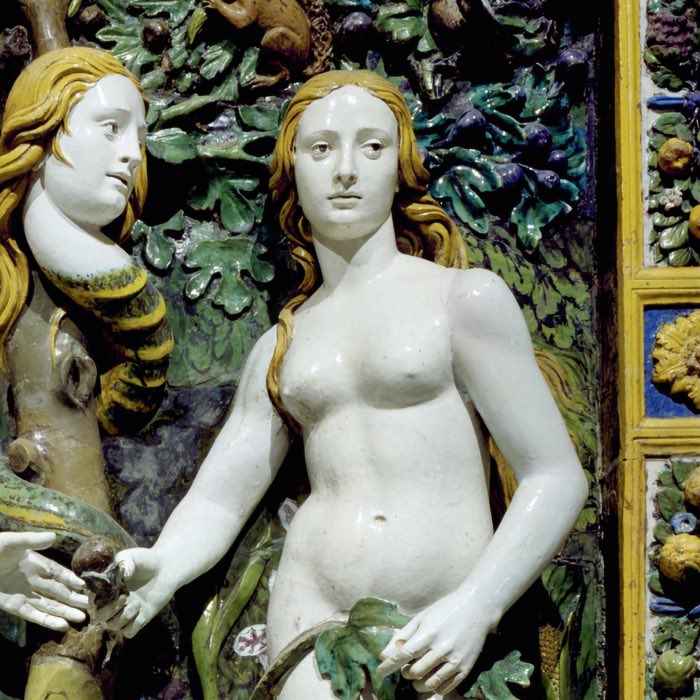

Phallic amulets made of bronze. Depictions with explicit erotic content were nothing unusual in Roman times. Obscene drawings and sayings smeared the walls, phallic amulets protected people and animals. Even relief depictions on fine tableware left nothing to be desired in terms of explicitness. Popular belief demanded the use of such symbols when it came to warding off the “evil eye” or intercession in the absence of a child’s blessing. And as a matter of course, Venus, the goddess of beauty and female grace, was depicted naked and placed on the household altar or in the temple as a votive offering. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Phallic amulets made of bronze. Depictions with explicit erotic content were nothing unusual in Roman times. Obscene drawings and sayings smeared the walls, phallic amulets protected people and animals. Even relief depictions on fine tableware left nothing to be desired in terms of explicitness. Popular belief demanded the use of such symbols when it came to warding off the “evil eye” or intercession in the absence of a child’s blessing. And as a matter of course, Venus, the goddess of beauty and female grace, was depicted naked and placed on the household altar or in the temple as a votive offering. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Clay figurines of the goddess Venus, around 100 CE. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Clay figurines of the goddess Venus, around 100 CE. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Lovers made of clay. A large number of private inscriptions document the everyday togetherness of lovers as a sign of tender attachment. The inscriptions and reliefs on many gravestones also convey the image of happy partnerships. Legally, however, women were at a disadvantage compared to their husbands. The Roman pater familias made the decisions and represented the family to the outside world, while his wife took care of the household; she was barred from practising many professions. The right to vote and stand for election was also reserved for men. In contrast, Roman divorce and inheritance law ensured a certain degree of financial independence for wives and daughters. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Lovers made of clay. A large number of private inscriptions document the everyday togetherness of lovers as a sign of tender attachment. The inscriptions and reliefs on many gravestones also convey the image of happy partnerships. Legally, however, women were at a disadvantage compared to their husbands. The Roman pater familias made the decisions and represented the family to the outside world, while his wife took care of the household; she was barred from practising many professions. The right to vote and stand for election was also reserved for men. In contrast, Roman divorce and inheritance law ensured a certain degree of financial independence for wives and daughters. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Brick fragment with love letter, accompanied by sexist caricatures. Translation of the inscription: … sends greetings to his dearest wife Mattosa and wishes that he can come back to you one day. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Brick fragment with love letter, accompanied by sexist caricatures. Translation of the inscription: … sends greetings to his dearest wife Mattosa and wishes that he can come back to you one day. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Clay bust of a woman with upwardly parted, elaborately coiffed hair with decorative disc, lunula pendant and ear ornaments, 1st third of the 2nd century CE. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Clay bust of a woman with upwardly parted, elaborately coiffed hair with decorative disc, lunula pendant and ear ornaments, 1st third of the 2nd century CE. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Hairpins made from bone. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Hairpins made from bone. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Bronze and iron fingers ring with blue and red gemstones gemstones. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Bronze and iron fingers ring with blue and red gemstones gemstones. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Bronze and iron finger ring with blue and red gemstones gemstones. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Bronze and iron finger ring with blue and red gemstones gemstones. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Silver ring with inscription: MATERN PAVLI Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Silver ring with inscription: MATERN PAVLI Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Enamel brooches. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Enamel brooches. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Reconstructed jewelry box of a wealthy lady with bronze lock, handle, fittings and key. Contents: enamel-decorated pair of disc brooches, enamel brooch with roundels on the sides, enamel brooch with openwork, oval bronze brooch, gold-plated, with blue gemstone, two ‘melon pearls’ made of blue glass frit, silver snake finger ring, bronze and bone hairpins, bronze sewing needle, two silver and bronze bracelets with wrapped ends, round bronze pocket mirror with white metal coating, and a pair of bronze tweezers. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Reconstructed jewelry box of a wealthy lady with bronze lock, handle, fittings and key. Contents: enamel-decorated pair of disc brooches, enamel brooch with roundels on the sides, enamel brooch with openwork, oval bronze brooch, gold-plated, with blue gemstone, two ‘melon pearls’ made of blue glass frit, silver snake finger ring, bronze and bone hairpins, bronze sewing needle, two silver and bronze bracelets with wrapped ends, round bronze pocket mirror with white metal coating, and a pair of bronze tweezers. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Leather shoe soles with remnants of iron hobnails from the Mainz area and iron hobnail. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Leather shoe soles with remnants of iron hobnails from the Mainz area and iron hobnail. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Imaginary reconstruction of a scene at the market in Nida. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Imaginary reconstruction of a scene at the market in Nida. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Lictor stone, sandstone, 1st quarter of the 2nd century CE. Relief block of a larger monument built from several blocks. On the left is a lictor, a servant and companion of high-ranking city officials. He is dressed in a tunic and hooded cloak and carries a staff in his left hand. The leg preserved at the bottom right, with a long robe and cloak, indicates a female figure, probably a goddess. It is possible that the stone was installed in an arch of honor that was erected to mark the founding of the CIVITAS TAUNENSIUM. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Lictor stone, sandstone, 1st quarter of the 2nd century CE. Relief block of a larger monument built from several blocks. On the left is a lictor, a servant and companion of high-ranking city officials. He is dressed in a tunic and hooded cloak and carries a staff in his left hand. The leg preserved at the bottom right, with a long robe and cloak, indicates a female figure, probably a goddess. It is possible that the stone was installed in an arch of honor that was erected to mark the founding of the CIVITAS TAUNENSIUM. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposed reconstruction of a Roman gate. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposed reconstruction of a Roman gate. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Architectural inscription, limestone, formerly red letters on a white background, western part of the vicus NIDA, from a cellar, 2nd century to 1st half of 3rd century CE. The inscription reads: SALVTI AVG(ustae)DENDROPHORI AVG(ustales)CONSISTENTES MED(…)IT(em) O(ue) NIDAE SCOLAMDE SVO FECERVNTLOC(o) ADSIG(nato) A VIC(anis) NIDE(nsibus) – For the salvation of the emperor. The dendrophores and priests of the imperial cult based in MED… and NIDA built the meeting house with their own funds. The land was given to them by the citizens of NIDA. The ancient name of the city of NIDA is documented here. At the same time, the inscription attests to a meeting house of the dendrophores (cult servants of the goddess Kybele = Magna mater), the imperial cult and the right of the citizens to allocate plots of land. MED… is probably Dieburg. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Architectural inscription, limestone, formerly red letters on a white background, western part of the vicus NIDA, from a cellar, 2nd century to 1st half of 3rd century CE. The inscription reads: SALVTI AVG(ustae)DENDROPHORI AVG(ustales)CONSISTENTES MED(…)IT(em) O(ue) NIDAE SCOLAMDE SVO FECERVNTLOC(o) ADSIG(nato) A VIC(anis) NIDE(nsibus) – For the salvation of the emperor. The dendrophores and priests of the imperial cult based in MED… and NIDA built the meeting house with their own funds. The land was given to them by the citizens of NIDA. The ancient name of the city of NIDA is documented here. At the same time, the inscription attests to a meeting house of the dendrophores (cult servants of the goddess Kybele = Magna mater), the imperial cult and the right of the citizens to allocate plots of land. MED… is probably Dieburg. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Replica of the armament and equipment of a Roman cavalry soldier around 100 CE. The lance (hasta) and long sword (spatha) were the typical offensive weapons of the Roman cavalry (equites alae). The three javelins (iacula) were carried in quivers hanging from the saddle. The upper body was protected by chain mail (lorica hamata), which consisted of around 30,000 iron rings and weighed 9 kg. Underneath, the soldiers wore two short-sleeved tunics (tunica) made of linen and thick woolen fabric. A neckerchief (focale) protected them from the cold and the impact of weapons. Leather breeches (feminalia) and a hooded cloak made of tumbled wool (paenula) completed the horsemen’s clothing. Like the foot soldiers, the horsemen wore nailed sandals (caligae). The cavalry helmet (cassis, galea) differed from infantry helmets in the 1st century due to its rich decoration. The round shield (clipeus) was protected against moisture and abrasion by a leather cover (tegimentum). The units could be distinguished from one another by the ornamental painting. Personal luggage included a small bronze bucket, a saucepan, spoon and knife for preparing food, as well as a canteen for thirst-quenching, slightly alcoholic vinegar water (posca). A net contained provisions for several days. A nutritious stew could be prepared with grain, bacon and cheese. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Replica of the armament and equipment of a Roman cavalry soldier around 100 CE. The lance (hasta) and long sword (spatha) were the typical offensive weapons of the Roman cavalry (equites alae). The three javelins (iacula) were carried in quivers hanging from the saddle. The upper body was protected by chain mail (lorica hamata), which consisted of around 30,000 iron rings and weighed 9 kg. Underneath, the soldiers wore two short-sleeved tunics (tunica) made of linen and thick woolen fabric. A neckerchief (focale) protected them from the cold and the impact of weapons. Leather breeches (feminalia) and a hooded cloak made of tumbled wool (paenula) completed the horsemen’s clothing. Like the foot soldiers, the horsemen wore nailed sandals (caligae). The cavalry helmet (cassis, galea) differed from infantry helmets in the 1st century due to its rich decoration. The round shield (clipeus) was protected against moisture and abrasion by a leather cover (tegimentum). The units could be distinguished from one another by the ornamental painting. Personal luggage included a small bronze bucket, a saucepan, spoon and knife for preparing food, as well as a canteen for thirst-quenching, slightly alcoholic vinegar water (posca). A net contained provisions for several days. A nutritious stew could be prepared with grain, bacon and cheese. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Living room with reconstructed wall and ceiling painting. The high-quality execution of the fresco indicates that the room was the living room of a wealthy middle-class family, who may have used it as a dining room. The dimensions of the room were derived from the graphic reconstruction of the approximately 6500 fragments that were excavated and partially assembled. The four medallions in the corners of the domed ceiling were dedicated to the seasons, which are symbolically represented by four busts crowned with flowers, ears of corn, vine leaves or covered with a veil. They stand for the cycle of nature, for growth and decay. The floating, embracing couple at the center of the ceiling comes from the Dionysian theme. The decoration of the walls follows the classic tripartite division of base - central field - frieze, in which cupids, sea creatures and birds cavort. Everyday scenes showing wealthy families at dinner or shopkeepers in the office were a popular motif on Roman tombs. They convey a detailed picture of the furniture of the time. The replicas on display here give us an impression of the upscale lifestyle that was certainly also cultivated in some of Nida’s houses. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Living room with reconstructed wall and ceiling painting. The high-quality execution of the fresco indicates that the room was the living room of a wealthy middle-class family, who may have used it as a dining room. The dimensions of the room were derived from the graphic reconstruction of the approximately 6500 fragments that were excavated and partially assembled. The four medallions in the corners of the domed ceiling were dedicated to the seasons, which are symbolically represented by four busts crowned with flowers, ears of corn, vine leaves or covered with a veil. They stand for the cycle of nature, for growth and decay. The floating, embracing couple at the center of the ceiling comes from the Dionysian theme. The decoration of the walls follows the classic tripartite division of base - central field - frieze, in which cupids, sea creatures and birds cavort. Everyday scenes showing wealthy families at dinner or shopkeepers in the office were a popular motif on Roman tombs. They convey a detailed picture of the furniture of the time. The replicas on display here give us an impression of the upscale lifestyle that was certainly also cultivated in some of Nida’s houses. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the reconstructed living room, showing a rattan armchair. The Roman Empire was known for its sophisticated furniture, which ranged from simple stools and benches to elaborate thrones and couches. The use of wood, metal, and textiles allowed for a wide variety of designs and styles, catering to different tastes and social classes. Furniture was an essential part of Roman homes, providing comfort, functionality, and aesthetic appeal. However, depending on the chosen material, furniture is rarely found in archaeological excavations. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the reconstructed living room, showing a rattan armchair. The Roman Empire was known for its sophisticated furniture, which ranged from simple stools and benches to elaborate thrones and couches. The use of wood, metal, and textiles allowed for a wide variety of designs and styles, catering to different tastes and social classes. Furniture was an essential part of Roman homes, providing comfort, functionality, and aesthetic appeal. However, depending on the chosen material, furniture is rarely found in archaeological excavations. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the reconstructed living room, showing glass vessels. The Roman Empire was renowned for its glass production, which ranged from everyday items like cups and bottles to luxury objects like jewelry and mosaics. Glassblowing techniques allowed for the creation of intricate designs and vibrant colors, making glassware a popular choice for both practical and decorative purposes. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the reconstructed living room, showing glass vessels. The Roman Empire was renowned for its glass production, which ranged from everyday items like cups and bottles to luxury objects like jewelry and mosaics. Glassblowing techniques allowed for the creation of intricate designs and vibrant colors, making glassware a popular choice for both practical and decorative purposes. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Terracotta figure with a colorful replica of an actor. The figure is wearing light muscle armor and has thrown on a cloak (sagum). A sword belt can be seen on the right shoulder. The figure is holding a theatrical mask with its mouth wide open in front of its chest. The figure probably depicts a milos gloriosus, who appeared as a grandiloquent soldier. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Terracotta figure with a colorful replica of an actor. The figure is wearing light muscle armor and has thrown on a cloak (sagum). A sword belt can be seen on the right shoulder. The figure is holding a theatrical mask with its mouth wide open in front of its chest. The figure probably depicts a milos gloriosus, who appeared as a grandiloquent soldier. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Game pieces made of bone on a reconstructed playing field (mill game). The Roman passion for games is documented by numerous finds and depictions, especially on grave monuments. Carvings of playing fields on paving stones and steps show that board games such as mills were part of the street scene. Game pieces and dice made of glass flux or bone also appear as grave goods. Children preferred throwing dice with knucklebones or nuces castellatae, in which they had to succeed in destroying small nut towers by throwing them in a targeted manner. Some of the ancient games have survived into modern times. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Game pieces made of bone on a reconstructed playing field (mill game). The Roman passion for games is documented by numerous finds and depictions, especially on grave monuments. Carvings of playing fields on paving stones and steps show that board games such as mills were part of the street scene. Game pieces and dice made of glass flux or bone also appear as grave goods. Children preferred throwing dice with knucklebones or nuces castellatae, in which they had to succeed in destroying small nut towers by throwing them in a targeted manner. Some of the ancient games have survived into modern times. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Handle of a folding knife (reconstruction). The original gladiator-shaped folding knife handle found in Frankfurt-Heddernheim in 188g has been lost. Thanks to a surviving ink drawing and a watercolor, however, it has been reconstructed. The exquisitely carved handle depicts a murmillo in a fighting stance. Characteristic features include the large, curved shield, the thick bandage with greaves, the short sword and the brimmed helmet. The short handle and the thin blade make it likely that it was used as a razor. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Handle of a folding knife (reconstruction). The original gladiator-shaped folding knife handle found in Frankfurt-Heddernheim in 188g has been lost. Thanks to a surviving ink drawing and a watercolor, however, it has been reconstructed. The exquisitely carved handle depicts a murmillo in a fighting stance. Characteristic features include the large, curved shield, the thick bandage with greaves, the short sword and the brimmed helmet. The short handle and the thin blade make it likely that it was used as a razor. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Wooden writing tablet (replica), iron and bronze writing stylus, spatula for smoothing the wax application. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Wooden writing tablet (replica), iron and bronze writing stylus, spatula for smoothing the wax application. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Inkwells made of clay. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Inkwells made of clay. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Inkwells made of glass. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Inkwells made of glass. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Iron garden and field tools: three-pronged fork. The soldiers in the Limes forts and their families, as well as the inhabitants of the civilian settlements, guaranteed the landowners and their tenants a secure supply of all products. New crops and previously unknown plants from the Mediterranean region increased yields and enriched the diet. Cultivated meadows provided fodder hay and made it possible to breed larger breeds of cattle and horses. Spelt and wheat fields, meadows and pastures as well as the introduction of the garden culture of fruit, vegetables and herbs, together with the numerous farmsteads, shaped the landscape of today’s Wetterau from the 2nd century onwards. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Iron garden and field tools: three-pronged fork. The soldiers in the Limes forts and their families, as well as the inhabitants of the civilian settlements, guaranteed the landowners and their tenants a secure supply of all products. New crops and previously unknown plants from the Mediterranean region increased yields and enriched the diet. Cultivated meadows provided fodder hay and made it possible to breed larger breeds of cattle and horses. Spelt and wheat fields, meadows and pastures as well as the introduction of the garden culture of fruit, vegetables and herbs, together with the numerous farmsteads, shaped the landscape of today’s Wetterau from the 2nd century onwards. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jar, Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Jar, Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Model and molding in clay of a terracotta figure, 2nd century CE, from the southern pottery district of Nida; it is the bust of an elderly, bald, beardless man, i.e. the caricature of a teacher (lector). Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Model and molding in clay of a terracotta figure, 2nd century CE, from the southern pottery district of Nida; it is the bust of an elderly, bald, beardless man, i.e. the caricature of a teacher (lector). Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Bronze statuette (laren) of Mercury, around 200 CE. The god of trade, merchants and thieves holds a filled purse in his right hand. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Bronze statuette (laren) of Mercury, around 200 CE. The god of trade, merchants and thieves holds a filled purse in his right hand. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Large oval single-handled jug, completed according to the base, wall and rim fragments. Between multicolored floral friezes a depiction of a sweating athlete, whose upper body and legs are preserved. A plant ornament below the handle. This unusual piece was probably made to order and could have been a prize at competitions, for example. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Large oval single-handled jug, completed according to the base, wall and rim fragments. Between multicolored floral friezes a depiction of a sweating athlete, whose upper body and legs are preserved. A plant ornament below the handle. This unusual piece was probably made to order and could have been a prize at competitions, for example. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: bronze box with compartments for holding. The Romans were highly developed and skilled in medicine and surgery, using a variety of instruments to treat injuries and illnesses. The tools on display at the museum provide a glimpse into the medical practices of the time, highlighting the ingenuity and expertise of Roman physicians. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: bronze box with compartments for holding. The Romans were highly developed and skilled in medicine and surgery, using a variety of instruments to treat injuries and illnesses. The tools on display at the museum provide a glimpse into the medical practices of the time, highlighting the ingenuity and expertise of Roman physicians. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: bronze windhook and 2 tweezers. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: bronze windhook and 2 tweezers. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: bronze spatulas, probe and spoon. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: bronze spatulas, probe and spoon. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: scalpel fragment and replica of a bronz scalpel. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: scalpel fragment and replica of a bronz scalpel. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: iron dental forceps. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Medical instrument: iron dental forceps. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt.

The decline and legacy of Nida

Nida, like many settlements along the Limes, faced challenges during the late Roman period. The growing pressure from Germanic tribes, coupled with internal political and economic crises, led to the eventual collapse of Roman control in the region. By the 4th century CE, Nida had diminished in significance, though its remnants continued to influence the cultural landscape of the area.

Today, Nida’s archaeological legacy is preserved and celebrated, offering invaluable insights into life on the Roman frontier. The findings from Nida contribute to our understanding of how Roman urbanization, trade, and cultural practices shaped the provinces and left enduring marks on the regions they touched.

Conclusion

The Roman vicus of Nida serves as a compelling case study of life in the provinces of the Roman Empire. Through its urban structure, economic activity, and cultural dynamics, Nida exemplifies the interconnectedness of the Roman world and the adaptability of its inhabitants. My visit to the Archäologisches Museum Frankfurtꜛ brought these facets to life, highlighting the richness of a settlement that once thrived on the edge of empire. I believe, that archaeological sites like Nida and associated museums play a crucial role in preserving and sharing the stories of the past, allowing us to understand the complexities of ancient societies and appreciate the legacies they have left behind.

References and further reading

- Ingeborg Huld-Zetsche, Nida – Eine römische Stadt in Frankfurt am Main, 1994, Schriften des Limesmuseums Aalen 48

- Peter Fasold, Die Römer in Frankfurt, 2017, Schnell & Steiner,ISBN 978-3-7954-3277-5

- Peter Fasold, Nida: Hauptort der civitas Taunensium, In: Vera Rupp, Heide Birley (Hrsg.): Landleben im römischen Deutschland, 2012, Theiss, ISBN 978-3-8062-2573-0

- Peter Fasold, Ausgrabungen im teutschen Pompeji. Archäologische Forschung in der Frankfurter Nordweststadt, 1997, Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Frankfurt am Main

- Carroll, Maureen, Romans, Celts & Germans: the German provinces of Rome, 2001, Tempus Series, Publisher: Tempus, ISBN: 0752419129

- Website of the Archäologisches Museum Frankfurtꜛ

comments