The cult of Mithras and Roman mystery religions: Christianity in a spiritual melting pot

The Roman Empire was a diverse and dynamic society, characterized by a remarkable degree of cultural and religious plurality. Its vast territory, encompassing a multitude of ethnic groups, languages, and traditions, became a fertile ground for the emergence and spread of new spiritual movements and mystery cults. Among these, the cult of Mithras stands out as one of the most enigmatic and influential. Christianity, which eventually rose to dominance within this pluralistic environment, potentially shares some overlaps with these contemporary religious traditions. In this post, we take a closer look at the cult of Mithras and its place within the spiritual landscape of the Roman Empire.

Slaying of a bull by Mithras, cult image, sandstone, 3rd century CE, part of a reconstruction of the Mithraeum III in Nida (near today’s Frankfurt am Main-Heddernheim), Germania Superior. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Slaying of a bull by Mithras, cult image, sandstone, 3rd century CE, part of a reconstruction of the Mithraeum III in Nida (near today’s Frankfurt am Main-Heddernheim), Germania Superior. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

A religiously pluralistic society

The Roman Empire was home to an extraordinary diversity of religious traditions and practices. Its vast territory, spanning Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, brought together countless local and imported deities, philosophies, and spiritual movements. This pluralism was not merely tolerated but often encouraged, as it contributed to the stability and cohesion of the empire by allowing individuals to maintain their cultural identities while participating in a broader Roman framework. Within this context, mystery religions and new spiritual movements found fertile ground for development, drawing adherents from all walks of life and shaping the spiritual landscape of the era.

Urbanization and mobility

The Roman Empire was marked by an unprecedented level of urbanization and mobility. Its extensive network of roads and shipping routes connected major cities and provinces, facilitating the movement of goods, ideas, and people. Cities like Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch became melting pots where diverse traditions converged. Soldiers, merchants, slaves, and travelers brought their religious practices and beliefs with them, leading to the intermingling of traditions and the formation of syncretic cults.

Philosophical inquiry

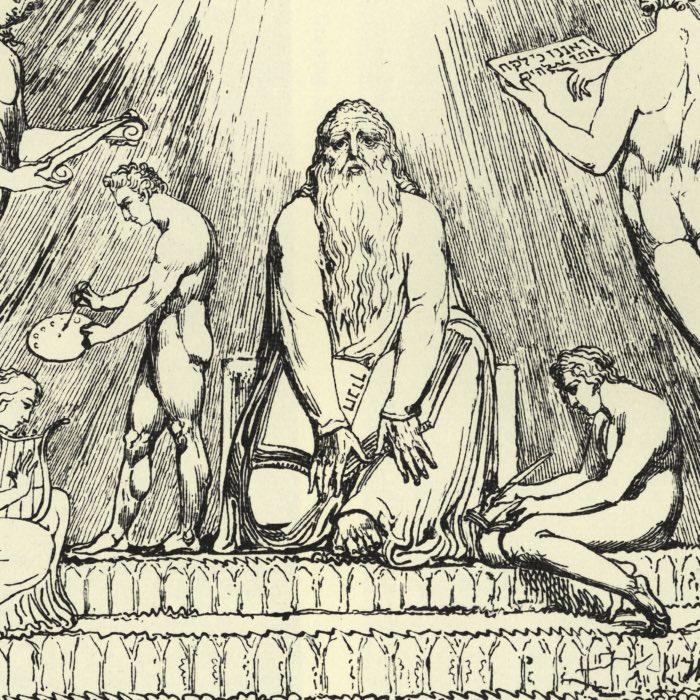

Hellenistic philosophical traditions, particularly Stoicism, Platonism, and Epicureanism, had a significant impact on religious thought in the Roman world. These schools of thought encouraged intellectual exploration and often sought to reconcile traditional religious practices with philosophical principles. Mystery religions, including the cult of Mithras, frequently incorporated philosophical elements, appealing to those seeking a deeper understanding of existence and the divine.

Crisis and uncertainty

The Roman Empire faced numerous crises, including political instability, economic difficulties, and external threats. These uncertainties fostered a widespread sense of insecurity, prompting many to seek solace in religions that offered personal salvation, spiritual transformation, and a sense of belonging. Mystery cults, with their promises of esoteric knowledge and immortality, became particularly attractive during these tumultuous times.

Religious liberalism

Roman authorities generally adopted a pragmatic approach to religion, allowing a wide array of traditions to flourish as long as they did not threaten public order or the emperor’s authority. This religious liberalism created an environment in which traditional Roman deities coexisted with imported gods and new religious movements. The resulting spiritual diversity provided fertile ground for the growth of mystery religions, including the cult of Mithras, and ultimately, Christianity.

The cult of Mithras

The Mithraic cult originated in the eastern regions of the Roman Empire, drawing inspiration from the Persian deity Mithra, a god associated with light, truth, and oaths. This ancient Indo-Iranian deity played a central role in Zoroastrianism as a protector of cosmic order and a mediator between the divine and human realms.

Relief at Taq-e Bostan: Investiture of Ardashir II with the depiction of Mithras behind and Ahura Mazda in front of the Sassanid Iranian Great King. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

However, when Mithraic practices were adopted and transformed within the Roman context, they diverged significantly from their Persian origins. The Roman Mithras cult was adapted to the cultural and spiritual milieu of the empire, integrating Greco-Roman religious elements and philosophical ideas. By the 1st century CE, Mithraism had evolved into a distinct mystery religion, emphasizing personal salvation, cosmic dualism, and the triumph of good over evil. Its secretive rituals, complex symbolism, and exclusive membership further underscored its unique character and appeal within the religiously pluralistic Roman world.

Rituals and symbolism

Central to Mithraic worship was the tauroctony, a depiction of Mithras slaying a bull, surrounded by a rich array of astrological symbols. This scene, interpreted as a cosmic act of creation and renewal, was the focal point of Mithraic iconography and embodied the connection between human destiny and the cosmos. The tauroctony symbolized the triumph of life over death and the renewal of the world, resonating deeply with Mithraic beliefs in cosmic dualism and personal salvation.

Membership in the Mithraic cult required elaborate initiation ceremonies, often held in underground temples called mithraea. These rites symbolized a spiritual journey, emphasizing purification, personal transformation, and the promise of salvation. Initiates progressed through a series of seven grades, each associated with specific symbols and rituals, such as wearing animal masks or participating in symbolic battles, which reflected their ascent through the cosmic hierarchy. These ceremonies created a sense of personal commitment and connection to the divine.

Mithraic rituals were rich in cosmic symbolism, frequently involving astrological imagery. The celestial motifs present in Mithraea reinforced the belief that human lives were interconnected with the movements of the heavens. The worship of Mithras was thus not merely an earthly act but a participation in a divine cosmic order. Such beliefs provided a framework for understanding life’s challenges and uncertainties, offering adherents both a sense of purpose and spiritual reassurance.

Communal meals played a significant role in Mithraic worship, fostering a strong sense of fellowship among members. These meals, which included the consumption of bread and wine, symbolized themes of life, renewal, and unity. This practice bears striking parallels to Christian Eucharistic traditions, though in Mithraism it was tightly linked to the exclusive bonds of the brotherhood. Mithraism appealed primarily to men, particularly soldiers, merchants, and officials, for whom its intimate and secretive communities offered not only spiritual guidance but also a powerful sense of belonging and loyalty. The exclusivity and moral discipline required of its members contributed to its allure, especially in an era marked by social and political upheaval.

Mithraism’s focus on personal salvation, moral purity, and the cosmic struggle between good and evil resonated deeply with many Roman citizens seeking profound spiritual meaning. Although Mithraism eventually declined, its rich rituals, emphasis on initiation, and vision of salvation left a lasting mark on the religious landscape of the Roman Empire.

Reconstruction of the Mithraeum in Nida

In Nida, a Roman vicus (settlement) in the Roman province of Germania Superior, near today’s Frankfurt am Main, a Mithraeum was discovered in 1907. The Mithraeum III, as it is known, was part of a larger sanctuary complex dedicated to the god Mithras. The Mithraeum was reconstructed for an exhibition in the Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurtꜛ, providing a realistic glimpse into the cult practices and beliefs of the Mithraic community. The reconstruction includes a proposal for the layout and decoration of the cult space, as well as the cult images and inscriptions found within the sanctuary.

Cover of the Mithras exhibition at the Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt. The cover illustrates a proposed reconstruction of the Mithraeum III in Nida (near today’s Frankfurt am Main-Heddernheim), Germania Superior.

Cover of the Mithras exhibition at the Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt. The cover illustrates a proposed reconstruction of the Mithraeum III in Nida (near today’s Frankfurt am Main-Heddernheim), Germania Superior.

Proposal for the reconstruction of the cult space of Mithraeum III of Nida. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposal for the reconstruction of the cult space of Mithraeum III of Nida. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposal for the reconstruction of the cult space of Mithraeum III of Nida. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposal for the reconstruction of the cult space of Mithraeum III of Nida. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Slaying of a bull by Mithras, cult image, sandstone, 3rd century CE, Nida. This motif is the most common depiction in Mithraic art and symbolizes the cosmic struggle between good and evil. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Slaying of a bull by Mithras, cult image, sandstone, 3rd century CE, Nida. This motif is the most common depiction in Mithraic art and symbolizes the cosmic struggle between good and evil. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Cautes, sandstone, 3rd century CE, Nida. Cautes, together with Cautopates, is one of the two torchbearers in the Mithraic cult, symbolizing the rising sun and the dawn. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Cautes, sandstone, 3rd century CE, Nida. Cautes, together with Cautopates, is one of the two torchbearers in the Mithraic cult, symbolizing the rising sun and the dawn. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Aeon (Aion), sandstone, 3rd century CE, Nida. An Aeon, around whose naked body a serpent often coils in a spiral, possibly represents a power subdued by Mithras, similar to Perseus defeating Gorgo/Medusa. It is assumed that the lion-headed god symbolizes the order of the cosmos in its entirety. A similar, also winged and serpent-wrapped figure is Aion or Phanes, who originated from the cult of Dionysus. In addition, the Zoroastrian embodiment of the negative principle, Ahriman, the adversary of the creator god Ahura Mazda, is depicted lion-headed and entwined with a serpent. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Aeon (Aion), sandstone, 3rd century CE, Nida. An Aeon, around whose naked body a serpent often coils in a spiral, possibly represents a power subdued by Mithras, similar to Perseus defeating Gorgo/Medusa. It is assumed that the lion-headed god symbolizes the order of the cosmos in its entirety. A similar, also winged and serpent-wrapped figure is Aion or Phanes, who originated from the cult of Dionysus. In addition, the Zoroastrian embodiment of the negative principle, Ahriman, the adversary of the creator god Ahura Mazda, is depicted lion-headed and entwined with a serpent. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Cautopates, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. Cautopates is the other of the two torchbearers in the Mithraic cult, symbolizing the setting sun and the twilight. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Cautopates, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. Cautopates is the other of the two torchbearers in the Mithraic cult, symbolizing the setting sun and the twilight. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposed floor mosaics of the Mithraeum III in Nida. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposed floor mosaics of the Mithraeum III in Nida. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Stele with dedication to Mithras and motifs from the Mithras legend, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. The inscription reads on the front: D(eo) IN(victo) M(ithrae)P(etram) GENETRICEMSENILIVS CARANTINVSC(ivis) MEDIOM(atricus) V(otum) S(olvit) L(ibens) L(aetus) M(erito)SIVE CRACISSIVS; on the left side, above Cautes with raised torch: CAVTE; below eagle on globe: C(a)ELVM (sky)Right side: above Cautopates with lowered torch: CAVT(o)P(ati);below personification of the ocean: OCEANVM(Consecrated) Senilius Carantinus, also known as Cracissius, citizen of the Civitas of the Mediomatricians (ancient capital: Divodurum Mediomatricorum/Metz) consecrated the depiction of the birth of the rock to the unconquered Mithras. He gladly and joyfully fulfilled his vow, as was fitting. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Stele with dedication to Mithras and motifs from the Mithras legend, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. The inscription reads on the front: D(eo) IN(victo) M(ithrae)P(etram) GENETRICEMSENILIVS CARANTINVSC(ivis) MEDIOM(atricus) V(otum) S(olvit) L(ibens) L(aetus) M(erito)SIVE CRACISSIVS; on the left side, above Cautes with raised torch: CAVTE; below eagle on globe: C(a)ELVM (sky)Right side: above Cautopates with lowered torch: CAVT(o)P(ati);below personification of the ocean: OCEANVM(Consecrated) Senilius Carantinus, also known as Cracissius, citizen of the Civitas of the Mediomatricians (ancient capital: Divodurum Mediomatricorum/Metz) consecrated the depiction of the birth of the rock to the unconquered Mithras. He gladly and joyfully fulfilled his vow, as was fitting. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the stele. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the stele. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Another detail of the stele. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Another detail of the stele. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Another detail of the stele. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Another detail of the stele. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Leo with the attributes bell and shovel, Mithraeum III of Nida, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Leo with the attributes bell and shovel, Mithraeum III of Nida, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Mithraic inscriptions and artifacts

The archaological museum in Frankfurt am Main further houses a collection of Mithraic inscriptions and artifacts, providing valuable insights into the beliefs and practices of the Mithraic cult. These inscriptions, often found on altars, pedestals, and relief sculptures, offer glimpses into the personal dedications and devotions of Mithraic worshippers. The artifacts, including reliefs, cult images, and symbolic representations, illustrate the rich iconography and symbolism of Mithraism, reflecting its emphasis on cosmic dualism, personal salvation, and the triumph of light over darkness. The collection also illustrates, that Mithras was worshipped along with or within the context of other deities, such as Fortuna, the goddess of luck and fate, or the Roman imperial cult.

Cautopates, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Cautopates, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar for Fortuna, sandstone, beginning of 2nd century CE(?). Reverse: Mithras carrying the bull. Inscription: FORTVN(ae)SACRVMTACITUS EQ(ues)ALAE I FLA(viae)T(urma) CL(audii) ATTICIV(otum) S(olvit) L(ibens) L(aetus) M(erito) – Dedicated to Fortuna. Tacitus, horseman of Ala I Flavia, from the Turma of Claudius Atticus, gladly and joyfully fulfilled his vow as was fitting. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar for Fortuna, sandstone, beginning of 2nd century CE(?). Reverse: Mithras carrying the bull. Inscription: FORTVN(ae)SACRVMTACITUS EQ(ues)ALAE I FLA(viae)T(urma) CL(audii) ATTICIV(otum) S(olvit) L(ibens) L(aetus) M(erito) – Dedicated to Fortuna. Tacitus, horseman of Ala I Flavia, from the Turma of Claudius Atticus, gladly and joyfully fulfilled his vow as was fitting. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Rock birth of Mithras, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. The rock birth of Mithras is a central motif in Mithraic iconography, symbolizing the god’s emergence from the primordial rock as a cosmic savior. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Rock birth of Mithras, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. The rock birth of Mithras is a central motif in Mithraic iconography, symbolizing the god’s emergence from the primordial rock as a cosmic savior. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Pedestal stone with inscription for Mithras, Sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Inscription: CAVIL(us) L(ucil) DOM(itii) AGISIL(I) (Servus) M(ithrae?) – Cavilus (slave of) Lucius Domitius Agisillus (or Agesilaus) (set the stone) for Mithras. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Pedestal stone with inscription for Mithras, Sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Inscription: CAVIL(us) L(ucil) DOM(itii) AGISIL(I) (Servus) M(ithrae?) – Cavilus (slave of) Lucius Domitius Agisillus (or Agesilaus) (set the stone) for Mithras. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar to Mithras, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Inscription: I(nvicto) M(ithrae)IVL(ius) IVVENA LIS (ex) V(oto) – (Consecrated) lulius luvenalis consecrated the altar to the unconquered Mithras in accordance with his vow. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar to Mithras, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Inscription: I(nvicto) M(ithrae)IVL(ius) IVVENA LIS (ex) V(oto) – (Consecrated) lulius luvenalis consecrated the altar to the unconquered Mithras in accordance with his vow. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar to Mithras, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. Inscription: D(eo) I(nvicto) M(ithrae)M(arcus) TER(entius) SENECIOP(ecunia) S(ua) P(osuit) – (Dedicated) To the unconquered god Mithras Marcus Terentius Senecio erected (the altar) from his money. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar to Mithras, basalt, 2nd/3rd century CE. Inscription: D(eo) I(nvicto) M(ithrae)M(arcus) TER(entius) SENECIOP(ecunia) S(ua) P(osuit) – (Dedicated) To the unconquered god Mithras Marcus Terentius Senecio erected (the altar) from his money. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar to Mithras, sandstone, beginning of 2nd century CE (?). Inscription: D(eo) /(nvicto) C(aius)LOLLIVSCRISPVSC(enturio) COH(ortis) XXXIIVOL(untariorum) – (Consecrated) To the unconquered (Mithras). Caius Lollius Crispus, centurion of the 32nd cohort, volunteer. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Altar to Mithras, sandstone, beginning of 2nd century CE (?). Inscription: D(eo) /(nvicto) C(aius)LOLLIVSCRISPVSC(enturio) COH(ortis) XXXIIVOL(untariorum) – (Consecrated) To the unconquered (Mithras). Caius Lollius Crispus, centurion of the 32nd cohort, volunteer. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Cautes, relief, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Cautes, relief, sandstone, 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Slaying of a bull by Mithras, revolving cult image, sandstone, End of 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Slaying of a bull by Mithras, revolving cult image, sandstone, End of 2nd/3rd century CE. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the revolving cult image (front side), showing the slaying of the bull motif. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the revolving cult image (front side), showing the slaying of the bull motif. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the revolving cult image (rear side), showing another scene of the slaying of the bull motif. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Detail of the revolving cult image (rear side), showing another scene of the slaying of the bull motif. Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Proposal for a coloring for the cult image above. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt

Proposal for a coloring for the cult image above. Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt

Proposal for a coloring for the cult image above (rear side). Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt

Proposal for a coloring for the cult image above (rear side). Archaeologisches Museum Frankfurt

Appeal

Mithraism primarily attracted men, particularly soldiers, merchants, and officials, due to its strong emphasis on discipline, loyalty, and communal bonds. Its hierarchical structure, which included seven distinct grades of initiation, reinforced a sense of order and progression that resonated deeply with the military ethos of the Roman Empire. These hierarchical grades were marked by symbolic rituals and transformative ceremonies, strengthening the members’ commitment to the cult and its values.

Mithraea have been discovered throughout the empire, from Britain to Syria, underscoring the widespread appeal and adaptability of the cult. These underground sanctuaries, often constructed to resemble caves, symbolized the mythological setting of Mithras’ cosmic deeds, particularly the tauroctony, or the slaying of the bull. The dim, intimate environment of Mithraea provided a space for secretive and deeply symbolic rituals that reinforced the cosmic and esoteric dimensions of Mithraism. Often located near military installations or urban centers, these sanctuaries served as focal points for community gatherings and spiritual reflection.

The cult’s exclusivity and its focus on moral discipline and personal salvation made it particularly appealing to those seeking deeper spiritual meaning and camaraderie. In a time of social and political upheaval, the structured and intimate nature of Mithraic communities provided members with both a sense of belonging and a framework for navigating the uncertainties of life. This combination of personal transformation, cosmic connection, and community solidarity contributed significantly to the cult’s success within the religiously diverse Roman Empire.

Christianity in a pluralistic context

Christianity thus emerged in a society already accustomed to religious diversity and syncretism. Early Christians operated within a landscape where numerous cults, including Mithraism, the Dionysus cult, the Isis cult, and the Eleusinian Mysteries, competed for adherents. This environment shaped Christianity’s development, as it navigated interactions with existing traditions while asserting its distinctive beliefs and practices. The similarities between Mithraism and Christianity, such as themes of personal salvation, moral transformation, and communal fellowship, suggest that early Christians may have drawn inspiration from or engaged with Mithraic ideas as they sought to establish their own religious identity.

Christianity distinguished itself through its monotheism and universalist message. Unlike the exclusivity of Mithraism, Christianity was open to all, regardless of social status or gender. Its emphasis on charity, forgiveness, and community created a compelling alternative to the hierarchical and secretive nature of many mystery cults. However, Christianity’s refusal to participate in state-sponsored rituals and its insistence on the sole worship of its deity brought it into conflict with Roman authorities.

The decline of Mithraism

The decline of Mithraism began in the 4th century CE, coinciding with the rise of Christianity as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Several factors contributed to Mithraism’s diminishing influence. Unlike Christianity, Mithraism’s exclusivity — limited primarily to men, particularly soldiers — restricted its appeal and hindered its ability to establish a broad-based following. The secretive nature of Mithraic rites and its lack of a centralized organizational structure further weakened its ability to compete with the increasingly institutionalized and state-supported Christian Church.

The Edict of Milan in 313 CE, which legalized Christianity, marked a turning point. With subsequent emperors, such as Theodosius I, endorsing Christianity and enacting laws against pagan practices, Mithraic worship faced growing suppression. By the late 4th and early 5th centuries, Mithraea were being abandoned or repurposed for Christian use, signaling the cult’s rapid decline.

Additionally, Christianity’s universalist message, emphasis on community, and promise of eternal salvation provided a more accessible and appealing spiritual framework for a diverse population. This inclusivity, coupled with the active proselytism of Christian missionaries, further marginalized Mithraism, which lacked comparable evangelistic efforts.

Over time, Mithraism gradually faded from public religious life. Without written scriptures or a centralized structure to preserve its teachings, the cult’s doctrines and practices were largely forgotten, surviving primarily through archaeological remains and fragmented artistic depictions. While some of its followers may have transitioned to Christianity, others were likely absorbed into local religious traditions or left without a communal spiritual home. Mithraism’s legacy persisted indirectly, potentially influencing early Christian iconography and rituals. For examples, the communal meals of the Mithraic brotherhoods, involving bread and wine, are thought to have influenced the early Christian Eucharistic practices. However, Mithraism’s distinct identity was ultimately lost within the shifting religious tides of late antiquity.

Conclusion

The Roman Empire’s religious pluralism created a dynamic spiritual landscape that fostered the growth of diverse mystery cults, including Mithraism and Christianity. The cult of Mithras, with its intricate symbolism, graded initiations, and cosmic focus, appealed primarily to men seeking discipline, solidarity, and spiritual purpose. Its exclusivity and emphasis on hierarchical rituals created tight-knit communities, but limited its broader appeal.

Christianity, by contrast, positioned itself as a universal religion open to all individuals, regardless of social status or gender – as long as you declare your faith in Christianity, of course. Its inclusive message, focus on charity and forgiveness, and the promise of eternal salvation attracted a wide audience, including marginalized groups who found solace and purpose in its teachings. Furthermore, Christianity’s communal practices fostered strong, supportive networks that extended beyond the confines of secretive or exclusive groups. While both Christianity and Mithraism shared themes of personal salvation and moral transformation, Christianity’s adaptability and universalist approach enabled it to outpace Mithraism in gaining followers across the Roman world.

References and further reading

- Beck, Roger, The religion of the Mithras cult in the Roman Empire, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199216130

- Philippa Adrych, Robert Bracey, Dominic Dalglish, Stefanie Lenk, Rachel Wood, Images of Mithra, 2017, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780198792536

- Turcan, Robert, The cults of the Roman Empire, 1996, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-0631200475

- Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians, 2006, Pneguin, ISBN: 978-0141022956

- Peter Fasold, Die Römer in Frankfurt, 2017, Schnell & Steiner,ISBN 978-3-7954-3277-5

- Ingeborg Huld-Zetsche, Nida – Eine römische Stadt in Frankfurt am Main, 1994, Schriften des Limesmuseums Aalen 48

- Carroll, Maureen, Romans, Celts & Germans: the German provinces of Rome, 2001, Tempus Series, Publisher: Tempus, ISBN: 0752419129

comments