The fututor of Carnuntum: Homosexuality in the Roman Empire

The discovery of an enigmatic tombstone in Carnuntum, an important Roman city on the Danube frontier, has sparked scholarly debate regarding its possible implications for understanding same-sex relationships in the Roman world. The inscription, attributed to Lucius Julius Faustus in honor of Lucius Julius Optatus, a physician, contains the puzzling term fututor, a word that classically refers to someone engaged in sexual activity. The presence of such a term on a funerary inscription is highly unusual, prompting speculation about the nature of the relationship between these two men. In this post, we briefly discuss homosexuality in the Roman Empire in general and explore the possible interpretations of the Carnuntum inscription.

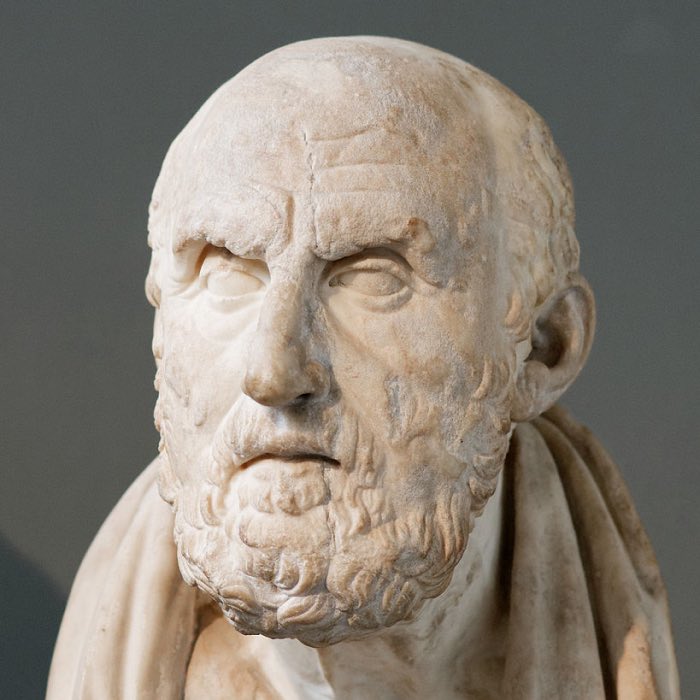

Busts of the Roman emperor Hadrian (left) and his male lover Antinous. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Homosexuality in the Roman Empire

Homosexuality in ancient Rome differed significantly from modern conceptions of sexual identity. Roman society did not categorize individuals based on their sexual preferences but instead judged relationships through the lens of power dynamics, social status, and masculinity. The central concern was not whether a man had sexual relations with another man but rather the roles each played in such encounters. Acceptable relationships were structured around the active-passive dichotomy, where the dominant partner was expected to be of higher social standing, while the passive partner was often of lower status, such as a slave, a freedman, or a younger man.

Heroic portrayal of Nisus and Euryalus by Jean-Baptiste Roman, 1827. Vergil described their love as pius in keeping with Roman morality. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

This perspective was deeply ingrained in Roman legal and cultural norms. While sexual relationships between men were widely acknowledged, societal scorn was directed toward freeborn Roman men who assumed the passive role, as it was seen as compromising their masculinity. Conversely, engaging in same-sex relations in a dominant role was not only tolerated but, in some cases, expected, particularly among the Roman elite, who demonstrated power and authority through their dominance over others.

Arretine earthenware with an erotic scene, artist unknown, 1st century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The literary and historical record suggests that attitudes towards male-male relationships were complex and varied. While some emperors and aristocrats engaged openly in such relationships, others faced political attacks and slander when their sexual conduct was perceived as undermining traditional Roman virtues. Given these cultural parameters, inscriptions such as the one found in Carnuntum offer a rare glimpse into how same-sex relationships might have been commemorated outside the confines of elite literature.

Left: Bust of Emperor Domitian, antique head, body added in the 18th century. Martial and Statius, two poets of the time, wrote a number of poems in which they celebrate the freedman Earinus, a eunuch, and his devotion to the emperor Domitian. Statius goes as far as to describe this relationship as a marriage. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Bust of Emperor Caligula. A young aristocrat by the name of Valerius Catullus boasted of penetrating the emperor Caligula during a lengthy intimate session. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Same-sex relations among women are far less documented in Roman sources, reflecting the patriarchal nature of Roman society. There are some scattered references, which attest to the existence of individual women who fell in love with members of the same sex. But the lack of detailed accounts and the prevailing focus on men in Roman literature make it challenging to reconstruct female-female relationships with the same level of detail as for male-male relationships.

Within Roman elite

The evidence for same-sex relationships in ancient Rome is overwhelmingly drawn from elite circles. This is due to the nature of historical preservation: members of the ruling class had the resources to commission inscriptions, monuments, and sculptures that have survived to the present day. The experiences of ordinary people, who did not have the means to leave behind such durable records, are largely lost to history. Additionally, ancient historians — whose works were often influenced by political and moral biases — focused almost exclusively on the behavior of the elite, particularly when it was seen as scandalous or controversial. Despite these limitations, several well-documented examples exist that provide insight into how same-sex relationships functioned within Roman society.

Hadrian and Antinous: The imperial precedent

One of the most famous same-sex relationships in Roman history is that between Emperor Hadrian (r. 117–138 CE) and his beloved Antinous. Antinous was a young Greek from Bithynia who became Hadrian’s close companion and, by all accounts, his lover. Their relationship followed the Hellenistic model of an erastes (older, dominant partner) and an eromenos (younger, receptive partner), a structure that was more widely accepted in Greek culture than in Rome itself.

The tondo at left depicting Hadrian’s lion hunt, accompanied by Antinous, on the Arch of Constantine in Rome. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Tragically, Antinous drowned in the Nile under mysterious circumstances in 130 CE, an event that devastated Hadrian. In response, the emperor deified him, an extraordinary act for a non-imperial individual. Cities were renamed in Antinous’ honor, temples were erected for his worship, and thousands of statues were commissioned across the empire, making him one of the most widely depicted figures of antiquity. The cult of Antinous endured for centuries, demonstrating that male-male relationships — at least when involving the ruling elite — could be openly commemorated.

Bust of Antinous-Dionysus from the Villa Adriana in Tivoli. The crown of the head, the bronze ivy crown and the torso are modern restorations. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Nero and his male spouses

The emperor Nero (r. 54–68 CE) provides another striking example of same-sex relationships in the Roman elite. Nero is reported to have had two publicly recognized marriages to men. The first was with a freedman named Pythagoras, whom he took as a spouse in a ceremony where Nero assumed the role of the “bride”. Later, Nero “married” a young boy named Sporus, whom he had castrated to resemble his deceased wife, Poppaea Sabina. Roman historians, particularly Suetonius and Cassius Dio, describe this relationship with a mix of moral outrage and fascination, underscoring the ways in which elite male-male unions could provoke strong reactions from their contemporaries.

Coin of Nero and Poppaea Sabina, Alexandria, Egypt. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nero’s marriages to men were exceptional in that they were performed with public ceremony and recognized as legitimate in a manner usually reserved for male-female unions. This suggests that, while not the norm, such relationships could be acknowledged in elite circles, especially when tied to imperial authority.

Julius Caesar and King Nicomedes IV

Julius Caesar, Rome’s most celebrated general, was famously rumored to have had a youthful relationship with King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia. According to ancient sources — including Suetonius, Cicero, and Cassius Dio — Caesar spent an extended period at Nicomedes’ court, leading to persistent rumors that he had engaged in a sexual relationship with the king. His enemies later used this against him, mockingly referring to him as the Queen of Bithynia. Despite these allegations, which followed him throughout his life, Caesar’s military and political success allowed him to avoid any serious reputational damage.

Left: Nicomedes IV depicted on a silver coin, ca. 94-74 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Caesar depicted on a coin, minted c. 44 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The case of Caesar and Nicomedes illustrates how Roman attitudes toward male-male relationships were shaped by power dynamics. The key source of ridicule was not the relationship itself, but the accusation that Caesar, a Roman aristocrat, had assumed a submissive role. In Roman society, masculinity was closely tied to dominance, and being perceived as the passive partner in a same-sex relationship was considered dishonorable for a freeborn Roman male.

Scipio Aemilianus and Laelius

A more understated but potentially significant example is the close companionship of Scipio Aemilianus (185–129 BCE) and his lifelong friend Gaius Laelius. While no explicit references to a sexual relationship exist, their deep personal bond was widely acknowledged in antiquity. The historian Polybius, a contemporary of both men, emphasized their close emotional connection, which he framed in terms of virtue and philosophical camaraderie.

The so-called “Hellenistic Prince”, tentatively identified as Scipio Aemilianus. Source left: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ, source right: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license left: CC BY-SA 2.0, right: public domain)

The absence of scandalous accusations against Scipio and Laelius may suggest that their relationship was purely one of friendship. However, it could also reflect the discretion with which Roman aristocrats could conduct same-sex relationships, particularly if they were careful to avoid violating social norms concerning masculinity and dominance.

Bias in the historical record

The examples above share one crucial feature: they all come from the elite. This is not necessarily because same-sex relationships were exclusive to the ruling class, but because history, as preserved through inscriptions and literary accounts, largely focuses on the actions of emperors, generals, and aristocrats.

For ordinary Romans, expressions of love — heterosexual or homosexual — would have been much less likely to survive in the historical record. Unlike Hadrian, a common soldier or merchant could not erect statues of his beloved across the empire. Unlike Nero, a plebeian could not afford to stage elaborate wedding ceremonies. This selective preservation means that while we have glimpses into elite same-sex relationships, the experiences of lower-class Romans remain largely invisible.

The tombstone from Carnuntum, however, stands out as a potential exception to this pattern. Although we do not know the exact social status of Lucius Julius Faustus and Lucius Julius Optatus, their inscription is not imperial or aristocratic in nature. If their relationship was indeed romantic, then this tombstone represents a rare example of non-elite, publicly expressed male-male affection in the Roman world.

The Carnuntum tombstone

Carnuntum was one of the most significant Roman settlements along the Danube, serving as both a military stronghold and a flourishing urban center. Located in present-day Austria, it was initially established as a Roman military camp in the first century CE, later develo∆ping into a full-fledged city with a population of over 50,000 inhabitants at its peak. As the capital of the province of Pannonia Superior, Carnuntum played a crucial role in trade, military strategy, and cultural exchange between the Roman world and the surrounding regions.

Carnuntum – Top: Model illustration of legionary camp in the foreground and civilian town in the top right. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Bottom: Model of the civil town of Carnuntum around 210 CE, in the center the Forum Baths and the Forum, in the background above the Amphitheater II (bottom). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Carnuntum – Top: Model illustration of legionary camp in the foreground and civilian town in the top right. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Bottom: Model of the civil town of Carnuntum around 210 CE, in the center the Forum Baths and the Forum, in the background above the Amphitheater II (bottom). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Model of the amphitheater II around 210 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The city’s importance is reflected in the extensive archaeological remains that have been uncovered, including an amphitheater, a military encampment, a civilian settlement, and various temples. Carnuntum was also home to a diverse population, consisting of Roman citizens, soldiers, traders, and local inhabitants who had assimilated into Roman culture. Inscriptions, coins, and sculptures found at the site provide valuable insight into the daily lives and social structures of its inhabitants.

General plan of the ancient settlement site of Carnuntum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The tombstone in question, dedicated by Lucius Julius Faustus to Lucius Julius Optatus, belongs to this rich archaeological landscape. Given Carnuntum’s status as a military and administrative hub, the presence of individuals like Optatus, a medicus (physician), suggests a well-developed infrastructure for medical practice and the care of soldiers and civilians alike. The use of Latin and the Roman naming convention (tria nomina) indicate that both men were either Roman citizens or had acquired citizenship, a privilege that was often granted to military personnel and their associates.

Intersection of Oststraße and Nordstraße at the Villa urbana, Carnuntum Archaeological Park. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Interior view of Tabernae. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

What makes this tombstone particularly remarkable is its inclusion of the term fututor, a word that is rare, especially in funerary contexts. This unique element has sparked ongoing debate about whether it signals an affectionate or romantic relationship between Faustus and Optatus. Unlike the well-documented same-sex relationships among the Roman elite, this inscription offers a potentially rare example of a more personal connection outside of imperial circles, shedding light on how such relationships might have been acknowledged in everyday life.

Reconstructed city villa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The inscription and its reconstruction

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any open-source images of the tombstone from Carnuntum that I could use to show you in this post. It looks similar to the one shown in the image below, which shows a Mithras altar found in Carnuntum:

Altar (308 CE) dedicated by the 4 Roman emperors Galerius, Licinius, Maximinus Daia and Constantin at their conference in Carnuntum to Mithras. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Copyright protected photographs of the tombstone can be found at the Epigraphic Database Heidelbergꜛ and at Ubi Erat Lupaꜛ. Please note that the images are copyrighted and cannot be used without permission.

The tombstone bears the following text:

L. IVLIVS OP-

TATVS MEDICVS

H·I·S·E·FVTVTOR

L. IVLIVS FAV-

STVS DE SVO

FECI

Artur Betz, the scholar who first published the inscription in 1964ꜛ (Selinger,2006ꜛ), reconstructed it as:

“L[ucius] Iulius Optatus medicus h[ic] i[ntus] s[itus] est. Fututor L[ucius] Iulius Faustus de suo feci.”

This translates to (Seliner, 2018ꜛ):

“Lucius Iulius Optatus, the physician, lies beneath this stone. As his lover, I, Lucius Iulius Faustus, had the tomb erected from his funds.”

While the basic elements of the inscription are clear, the term fututor presents significant interpretative challenges. In classical Latin, the word is a vulgar term for someone who engages in sexual intercourse, often in an active or dominant role. Its use in a formal funerary context is unprecedented, raising questions about whether it was intended literally, figuratively, or perhaps as a misunderstood or corrupted inscription.

Possible interpretations of fututor

The conventional meaning: A sexual reference

The most straightforward interpretation of fututor aligns with its usual lexical meaning. If taken literally, the inscription would be an extraordinary case of a Roman epitaph explicitly referencing sexual relations between two men. Such a reading aligns with known Roman attitudes toward male-male sexuality, in which social status, rather than gender, dictated the acceptability of a sexual relationship. As described in the introduction, Roman men could engage in relationships with other men, provided they maintained the active role, particularly in relationships with younger men or those of lower social standing.

If fututor is to be taken at face value, it suggests that Faustus either wished to commemorate his physical relationship with Optatus or, perhaps more plausibly, that he used the term with an affectionate or humorous undertone, marking their bond in a way that defied conventional funerary language.

Alternative explanations

Scholars have proposed alternative explanations, each attempting to mitigate the surprising nature of the term:

- A non-literal or affectionate use – Some scholars argue that fututor here could have a figurative meaning, possibly akin to a playful or affectionate nickname. The funerary context makes a crude reference unlikely unless it had a more personal, nuanced meaning between the two men.

- A scribal or linguistic error – Given the rarity of such explicit language in epitaphs, some have suggested that the word might be a miswriting, abbreviation, or otherwise misunderstood inclusion.

- An inside joke or expression of defiance – While funerary inscriptions were usually formal, there are cases of unusual, even humorous, dedications in the Roman world. It is possible that the term fututor was included in a way that was meant to be understood only by those familiar with the relationship between the two men.

The weight of the evidence

While alternative explanations exist, none fully resolve the peculiarity of the inscription. If fututor were simply a mistake, why was it not corrected? If it was a joke or playful reference, why was it used in a solemn funerary context? The most plausible explanation remains that it was intended to reflect the nature of the relationship between Faustus and Optatus in a way that was meaningful to them.

The fact that Faustus not only dedicated but also personally funded the monument (de suo fecit) adds weight to the hypothesis that their bond was particularly deep. While patronage and friendship could account for this generosity, the inclusion of fututor suggests something beyond conventional friendship or collegial respect.

Roman attitudes toward male-male relationships

Roman attitudes toward same-sex relationships were complex. While Roman men could engage in relationships with other men, the key factor was the maintenance of social and gendered hierarchies. A freeborn Roman man was expected to take the active role in any sexual encounter; passive participation, particularly among freeborn men, was seen as shameful.

In this context, the inscription’s possible acknowledgment of a sexual relationship is remarkable. If fututor is a self-referential term describing Faustus, it reinforces the notion that their relationship was not merely affectionate but physical. That such a statement was made on a public monument suggests a level of openness about their relationship that challenges traditional narratives of Roman sexuality being strictly confined to dominance and hierarchy.

Homosexuality in the Roman military and frontier regions

Carnuntum, as a Roman military and administrative center, was a cosmopolitan hub where social norms may have been more fluid than in the heart of Rome. It is well-documented that in military settings, strong bonds between men were common, sometimes extending into romantic or sexual relationships (Masterson (2016); Chrystal (2016)). The presence of a medicus (Optatus) and the possible implications of his relationship with Faustus suggest that professional and emotional bonds could have overlapped.

While Rome’s ruling elite often adhered to stricter social norms, the frontier regions of the empire may have permitted a more open expression of same-sex relationships. The presence of fututor in this inscription might indicate that within certain subcultures or communities, such expressions were not entirely taboo.

The impact of Christianity on same-sex relationships

As Christianity gained prominence in the Roman Empire, attitudes toward same-sex relationships underwent a significant transformation. The perception of Roman sexual practices as morally decadent can be largely attributed to early Christian polemics, which sought to contrast Christian morality with the perceived excesses of pagan society. This shift in ideology ultimately led to a series of legal changes that criminalized same-sex relationships and redefined acceptable social and sexual behavior.

The first recorded legal action against male-male sexual activity came under Emperor Philip the Arab in the 3rd century CE, when male prostitution was officially banned. Throughout the 3rd century, amid increasing social and political instability, additional laws were introduced that targeted male-male sexual relationships. These laws covered a range of issues, from prohibiting sexual relationships between men and minors to banning same-sex marriages.

By the late 4th century, as Christianity became the dominant state religion, punishments for same-sex relationships became more severe. Under the Christian emperors, passive male partners in same-sex acts were increasingly criminalized, with some subjected to execution by burning. The Theodosian Code, compiled under Emperor Theodosius II in the early 5th century, explicitly condemned same-sex acts, prescribing death by the sword for men who “coupled like a woman”.

The most stringent measures came under Emperor Justinian in the 6th century, marking a complete departure from earlier Roman legal attitudes. Justinian’s laws classified all male-male sexual activity—regardless of role or social status—as contrary to nature and punishable by death. The emperor and his legal scholars tied same-sex acts to divine punishment, blaming them for disasters such as plagues and military defeats. This marked a transition from viewing such relationships as matters of social order and hierarchy to outright moral and theological condemnation rooted in Abrahamic religious doctrine.

These legal and moral transformations under Christian rule led to the erasure of previously tolerated or accepted expressions of same-sex relationships in Roman society. Over time, the rhetoric of moral purity and divine retribution replaced the earlier pragmatism of Roman legal and cultural traditions, setting the foundation for medieval and later Christian attitudes toward homosexuality.

We will discuss the persecution of condemnation of homosexuals under Christian rule in more detail in a later posts.

Conclusion

The Carnuntum inscription offers a unique, albeit ambiguous, glimpse into the personal relationships of non-elite individuals in the Roman world. While the precise nature of the bond between Lucius Julius Faustus and Lucius Julius Optatus remains uncertain, the use of the term fututor on a funerary monument challenges our understanding of Roman attitudes toward same-sex relationships. If interpreted in favor of a romantic connection, this inscription provides one of the rare examples of publicly expressed same-sex affection outside of literary or elite contexts.

However, this interpretation must be approached with caution. The historical record is shaped by biases—both ancient and modern—that influence our readings of such evidence. Roman society did not categorize relationships based on sexual orientation as in the modern sense but instead focused on social hierarchy and dominance. Whether fututor signifies a genuine acknowledgment of a same-sex relationship or serves another function entirely, its presence in a formal epitaph is noteworthy.

The broader historical trajectory of same-sex relationships in Rome further complicates this discussion. The early tolerance of certain forms of male-male relationships gave way to increasing regulation, particularly with the rise of Christian moral frameworks that ultimately criminalized and erased previously accepted expressions of same-sex intimacy. The fate of the Carnuntum inscription — buried for centuries, rediscovered only recently — mirrors the broader fate of queer history: overlooked, obscured, yet still persistent in the archaeological and historical record.

Ultimately, the significance of the Carnuntum inscription lies not just in what it reveals about the past, but in the questions it raises about how history is written, remembered, and interpreted. It serves as a reminder that personal relationships, even in antiquity, were complex and deeply human, transcending the rigid moral structures imposed by later ideologies.

So far, I did not have the opportunity to visit Carnuntum, but I hope to do so in the future. As soon as I have the chance to see the archaeological site, I will share my impressions with you.

References and further reading

- Craig A Williams, Roman homosexuality: Ideologies of masculinity in classical antiquity, 1999, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780195125054

- Mark Masterson, Man to Man: Desire, Homosociality, and Authority in Late Roman Manhood, 2016, The Ohio State University Press, ISBN: 978-0814253014

- Paul Chrystal, Roman Military Disasters: Dark Days & Lost Legions, 2016, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, ISBN: 978-1473823570

- Halperin, David M., One hundred years of homosexuality: And other essays on Greek love. 1990, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415900973

- Hubbard, Thomas K., Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A sourcebook of basic documents, 2003, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520234307

- Hubbard, Thomas K., Historical Views of Homosexuality: Roman Empire, 2020, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1243ꜛ

- Cantarella, Eva, Bisexuality in the ancient world, 1992, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300048445

- Richlin, Amy, The garden of Priapus: Sexuality and aggression in Roman humor, 1992, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195068733

- Clarke, John R., Sexuality and Visual Representation, In: A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities, edited by Thomas K. Hubbard, 2013, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405195720

- Skinner, Marilyn B., Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture, 2005, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-0631232346

- John R. Clarke, Looking at Lovemaking. Constructions of Sexuality in Roman Art 100 B.C.–A.D. 250, 2001, University of California Press, Berkeley ISBN 978-0520229044

- A. Betz, Das Grabmal des Optatus medicus, Carnuntum Jahr-buch 1961/62, 84-86 (Taf. XV, 1-2), (AE 1969/70, 502), iDAI.bibliographyꜛ

- Selinger, Reinhard, Der fututor aus Carnuntum, Moderne Altertumswissenschaften und römische Sexualität, Klio, vol. 88, no. 2, 2006, pp. 516-524, (AE 1969/70, 502), doi: 10.1524/klio.2006.88.2.516ꜛ

- Selinger, Reinhard, Homo- Oder Heterosexuell? Noch Einmal Zum Fututor Aus Carnuntum, 2018, Glotta, vol. 94, pp. 264–72. (AE 1969/70, 502), JSTORꜛ

- Epigraphic Database Heidelbergꜛ showing an image of the Lucius Iulius Optatus tombstone (Copyright protected)

- Ubi Erat Lupa – Bilddatenbank zu antiken Steindenkmälernꜛ showing several images of the Lucius Iulius Optatus tombstone (Copyright protected)

- Franz Humer, Carnuntum. Wiedergeborene Stadt der Kaiser, 2014, Philipp von Zabern in Herder, ISBN: 978-3805347181

- Franz Humer, Eine kurze Geschichte Carnuntums, In: Franz Humer (Hrsg.): Ein römisches Wohnhaus der Spätantike in Carnuntum, Archäologischer Park, Die Ausgrabungen 5, St. Pölten 2009, S. 4–27.

- Franz Humer, Marc Aurel und Carnuntum, 2004, Amt der NÖ Landesregierung – Abteilung Kultur und Wissenschaft, ISBN: 978-3854602170

- Werner Jobst, Provinzhauptstadt Carnuntum. Österreichs größte archäologische Landschaft, 1983, Österreichischer Bundesverlag, ISBN: 3-215-04441-2

- Eduard Vorbeck, Lothar Beckel, Carnuntum. Rom an der Donau, 1973, Otto Müller

- Wikipedia article on Carnuntumꜛ

- Website of the Carnuntum Archaeological Parkꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Homosexuality in ancient Romeꜛ

comments