Mother of God cult in the Roman empire and its transformation into Marian devotion

The veneration of Mary, the proclaimed Mother of Jesus, holds a central place in Christianity today, but its development is deeply rooted in the religious and cultural traditions of the Roman Empire. Far from being a concept that emerged fully formed, the cult of Mary evolved gradually, shaped by both theological debates within early Christianity and the broader cultural influences of maternal archetypes from Greco-Roman religions. This synthesis allowed Christianity to appeal to a diverse audience in a pluralistic empire while providing continuity for converts from other faiths. This post explores the origins, development, and significance of Marian devotion, focusing on how it emerged from and transformed existing traditions.

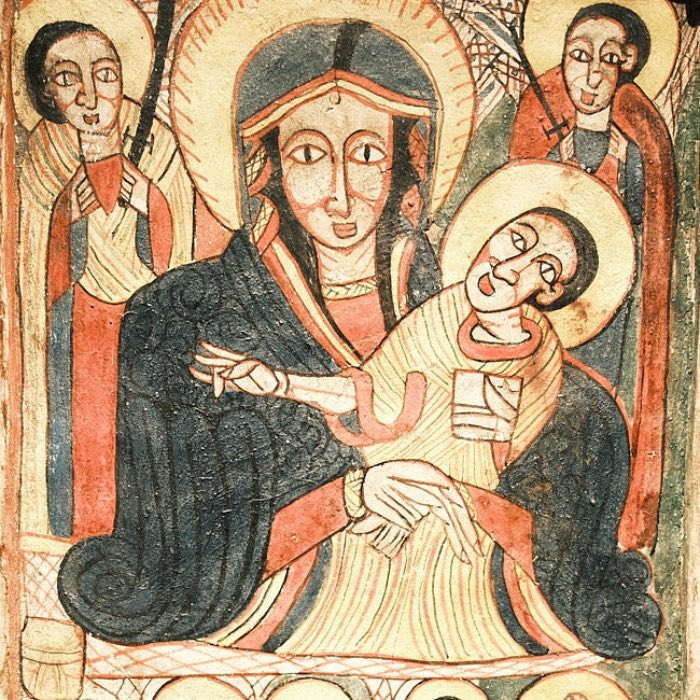

Mother of God (Vladimirskaya), Russia, around 1750, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Mother of God (Vladimirskaya), Russia, around 1750, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Maternal archetypes in the Roman world

The Roman Empire was a melting pot of religious traditions, many of which celebrated divine maternal figures as sources of protection, fertility, and salvation. Central to the religious life of the empire were cults that venerated mother goddesses, including Isis, Cybele, and Demeter, whose attributes and imagery bore striking similarities to later depictions of Mary.

The cult of Isis

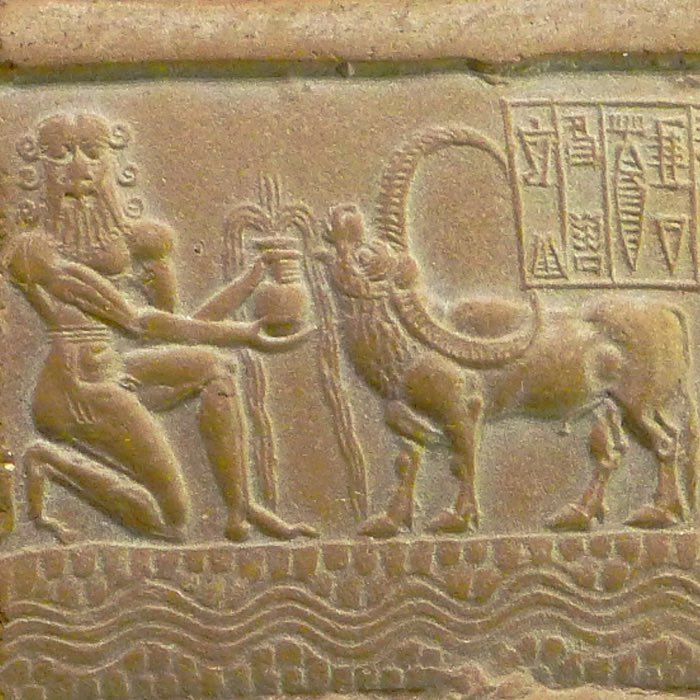

The Egyptian goddess Isis was among the most influential maternal deities in the Greco-Roman world. Her cult, which spread widely during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, emphasized themes of motherhood, magic, and personal salvation. Isis was often depicted nursing her son Horus, symbolizing maternal care and divine protection. This image resonated deeply with devotees across the empire, offering an intimate and accessible relationship with the divine.

Left: Isis nursing Horus, a sculpture from the 7th century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Isis Lactans holding Harpocrates in an Egyptian fresco at Karanis, dating to the 4th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The rituals and theology of the Isis cult focused on individual devotion, ritual purification, and the promise of life after death. These elements would later find echoes in Christian practices, particularly in the emphasis on Mary as a nurturing and intercessory figure who bridges the gap between humanity and the divine.

Cybele and the Magna Mater

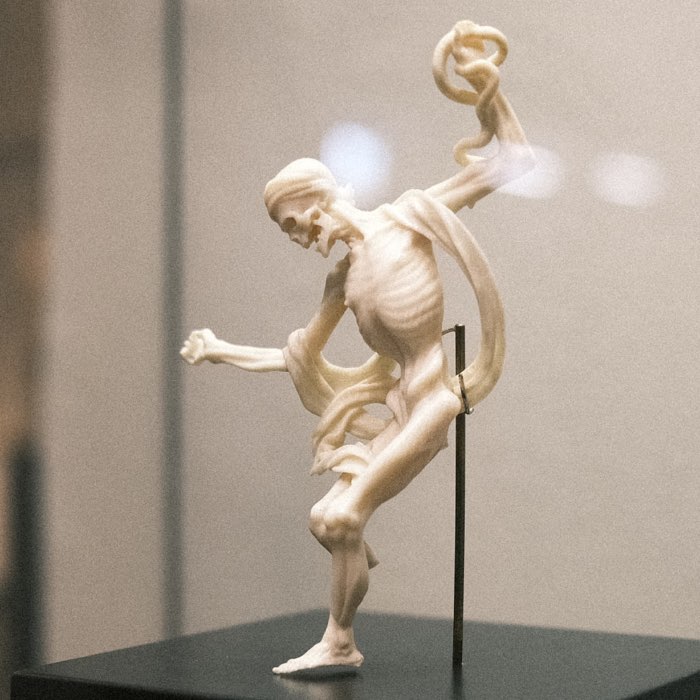

Another prominent maternal figure was Cybele, known as the Magna Mater (“Great Mother”). Originating in Phrygia (modern Turkey) and adopted into Roman religion, Cybele represented fertility, nature, and the protective power of motherhood. Her cult involved ecstatic rituals, music, and dance, highlighting the emotional and spiritual connection between the goddess and her followers.

Left: Cybele enthroned, with lion, cornucopia, and mural crown. Roman marble, c. 50 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Bronze fountain statuette of Cybele on a cart drawn by lions 2nd century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Cybele’s role as a universal mother figure, embodying the life-giving and protective forces of nature, would later be paralleled in Christian depictions of Mary as the nurturing Mother of God, offering protection and salvation to her spiritual children.

Demeter, Juno, and other goddesses

Figures like Demeter, the Greek goddess of agriculture and motherhood, and Juno, the Roman queen of the gods, further reinforced the cultural prominence of maternal archetypes. These goddesses were associated with themes of renewal, familial care, and protection, creating a religious environment that readily embraced the veneration of Mary as a universal mother.

Left: Juno-Hera fresco from Pompeii. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Demeter, enthroned and extending her hand in a benediction toward the kneeling Metaneira, who offers the triune wheat, c. 340 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The emergence of Marian devotion in early Christianity

As Christianity began to spread within the Roman Empire, it encountered a religious landscape deeply shaped by these maternal archetypes. The veneration of Mary emerged gradually, influenced by both internal theological developments and external cultural factors.

The “virgin” narrative

The concept of Mary’s virginity has been a pivotal element of Marian devotion, but it is important to examine the translation and interpretation of the word “virgin” in its historical and linguistic context. The New Testament’s Greek term “parthenos”, used to describe Mary, can mean both “virgin” and “young woman”. This term was likely a translation of the Hebrew word “almah” found in Isaiah 7:14, which also means “young woman” rather than exclusively indicating virginity. Over time, Christian theology emphasized the interpretation of “parthenos” as “virgin” to align with doctrinal developments that portrayed Mary as uniquely pure and divinely chosen. This linguistic choice played a significant role in constructing the theological narrative of the virgin birth and solidifying Mary’s role as the Mother of God.

Inventing a biography

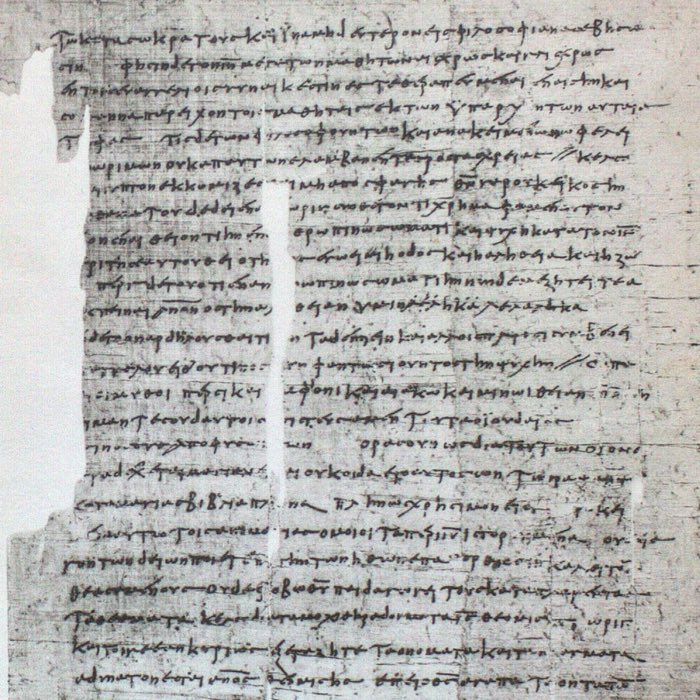

Mary, who is actually rarely mentioned in the New Testament – she is mentioned just 142 of the approximately 8000 verses of the New Testament – and whose life story is largely absent, including after the Crucifixion narrative, became the subject of a complete invented biography outside the canonical texts. Apocryphal works like the Protoevangelium of James sought to historize this largely fictive biblical figure, attributing to her a detailed vita that emphasized her purity, divine selection, and centrality in salvation history.

This invented biography included key stages such as her miraculous conception by her elderly parents Joachim and Anne, her dedication to the Temple at a young age, and her divine selection to be the mother of Jesus. It also described events like her betrothal to Joseph, her virgin birth of Jesus, her lifelong commitment to purity and holiness, and her Dormition — the narrative of her peaceful death and miraculous assumption into heaven. These narratives not only filled gaps in her life story but also elevated her theological status, reinforcing her significance in salvation history and legitimizing her veneration in the emerging Christian tradition.

Annunciation of the birth of Mary to Joachim and Anna, fresco by Gaudenzio Ferrari, 1544–45 (detail). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The presentation of the Virgin in the temple, an event that only appears in the Gospel of James, depicted on a Russian icon. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Pre-annunciation at the Well, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Pre-annunciation at the Well, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Mother of God unexpected joy, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Mother of God unexpected joy, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Mother of God unexpected joy (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Mother of God unexpected joy (detail), Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Birth of Mary, Mother of God (detail), Russia, late 18th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Birth of Mary, Mother of God (detail), Russia, late 18th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Dormition of the Mother of God, Russia, 19th century, Brass, enamelled, four colours. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Dormition of the Mother of God, Russia, 19th century, Brass, enamelled, four colours. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

As Christianity began to spread within the Roman Empire, it encountered a religious landscape deeply shaped by these maternal archetypes. The veneration of Mary emerged gradually, influenced by both internal theological developments and external cultural factors.

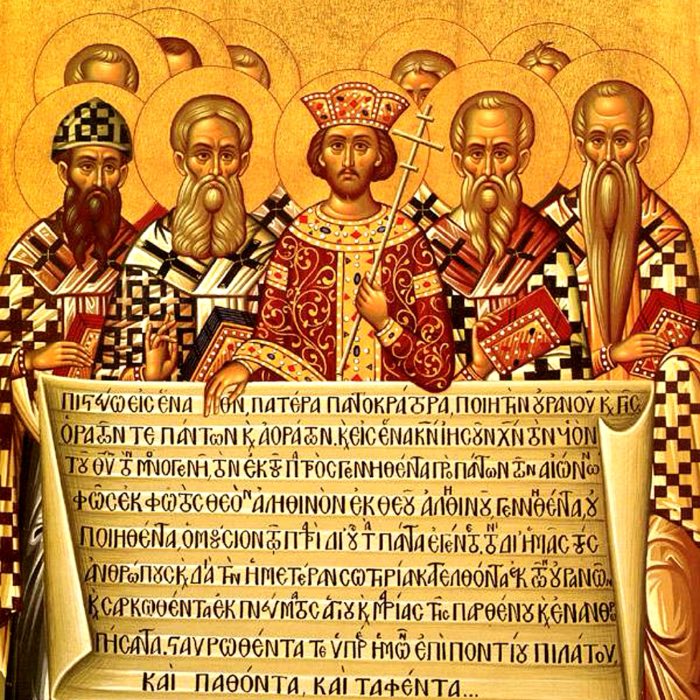

Mary as Theotokos

The title Theotokos (Greek for “God-Bearer”) became a defining aspect of Marian devotion. Officially affirmed at the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE, this title emphasized Mary’s role as the mother of Jesus, who was both fully human and fully divine. The affirmation of Mary as Theotokos was not only a theological statement about the nature of Christ but also a reflection of the growing veneration of Mary as a central figure in Christian spirituality.

Madre della Consolazione (Our Lady of Consolation), Italian-Cretan, around 1500, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Madre della Consolazione (Our Lady of Consolation), Italian-Cretan, around 1500, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

The Council of Ephesus took place in a city long associated with the worship of Artemis, a goddess revered for her role as a protector of women and children. The declaration of Mary as Theotokos in this context symbolized the transition from pagan maternal cults to Christian devotion, aligning Mary with the protective and nurturing qualities that had long been celebrated in other religious traditions.

The influence of early Christian texts

The Protoevangelium of James, a second-century apocryphal text, played a significant role in shaping early Marian theology. It emphasized Mary’s purity, divine selection, and unique role in salvation history, contributing to her veneration as a figure of exceptional holiness. This text, along with early Christian hymns and prayers, laid the groundwork for Marian devotion by presenting Mary as both a model of faith and a maternal intercessor.

The Miriam-Mary connection

An often-overlooked aspect of Marian devotion is its potential link to the biblical figure Miriam, the sister of Moses. Miriam, as described in the Hebrew Bible, played a pivotal role in the liberation narrative of the Israelites. She was a prophetess and a figure of salvation, leading the Israelites in song and dance after crossing the Red Sea.

Early Christian thinkers and writers may have drawn a symbolic connection between Miriam and Mary. Both names derive from the same Hebrew root (Miryam), and both figures hold prominent roles as women associated with divine intervention and deliverance. For Jewish-Christian audiences, this connection would have provided a bridge between the revered traditions of the Hebrew Bible and the emerging devotion to Mary in Christian theology. Moreover, this link served a dual purpose: legitimizing Christianity within its Jewish roots while also elevating Mary as surpassing Miriam. Unlike Miriam, whose role was limited to leading and prophesying, Mary was portrayed as giving birth to God, thus positioning her as an even more powerful and central figure in the narrative of salvation history. Early Christianity was in need of such narratives in order to establish itself apart from Judaism and other religions of the time.

The Development of Marian Practices

By the 4th century CE, prayers and hymns to Mary were becoming an integral part of Christian worship, particularly in the Eastern Church. Feasts such as the Annunciation and the Assumption began to honor Mary’s unique role in salvation history, while Marian icons depicted her as a compassionate and intercessory figure.

These practices mirrored earlier pagan traditions, providing continuity for converts from Greco-Roman religions. Just as devotees of Isis and Cybele sought protection and guidance from their goddesses, Christians began to turn to Mary as a source of comfort and divine intercession.

Cultural adaptation

The transition from the maternal cults of the Roman Empire to the veneration of Mary was marked by both take-ober and transformation. While Christianity rejected the polytheistic framework of Greco-Roman religion, it retained and reinterpreted many of its symbols and practices.

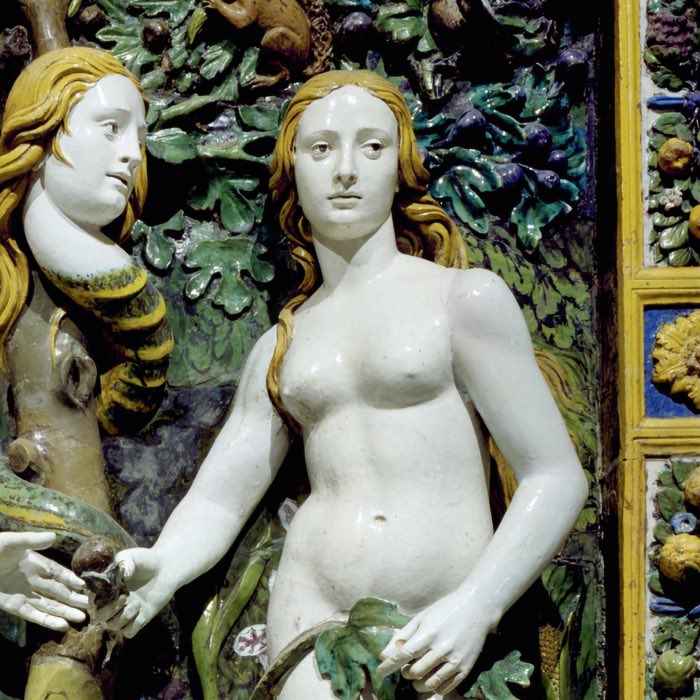

Imagery and iconography

One of the most striking examples of this cultural take-over is the depiction of Mary nursing the infant Jesus, an image that closely resembles earlier portrayals of Isis nursing Horus. This motif was reinterpreted as Mary, a nurturing mother, providing spiritual sustenance and care for her followers.

Mother of God of Kazan (Kazanskaya), Russia, after 1800, egg tempera on wood, gilded oklad, with coloured stones. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Mother of God of Kazan (Kazanskaya), Russia, after 1800, egg tempera on wood, gilded oklad, with coloured stones. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Similarly, depictions of Mary enthroned echoed the regal imagery of goddesses like Juno and Cybele. However, in Christian art, Mary’s throne was often imbued with theological significance, stating her role as the Queen of Heaven and her intimate connection to the divine.

Mother of God Life-Giving Source, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Mother of God Life-Giving Source, Russia, 19th century, egg tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Pilgrimage and shrines

The emergence of Marian shrines and pilgrimage sites also reflected the influence of earlier religious practices. Sites such as the Church of Mary in Ephesus became centers of devotion, drawing pilgrims who sought Mary’s intercession and protection. These practices mirrored the pilgrimages undertaken by devotees of Isis, Cybele, and other deities, reinforcing the universal appeal of maternal figures in religious life.

Marian devotion as a unifying force

The cult of Mary played a crucial role in the spread and consolidation of Christianity in the Roman Empire. Her universal motherhood transcended cultural and social boundaries, providing a unifying symbol for diverse communities of believers.

Inclusivity and accessibility

Mary’s role as the “Mother of God” offered an inclusive and accessible image of divine care, appealing to both Jewish and Gentile converts. Her maternal attributes resonated with existing cultural norms, making Christianity more relatable to those familiar with Greco-Roman religious traditions.

Continuity and transformation

By integrating elements of maternal archetypes from Greco-Roman religion, Marian devotion provided a sense of continuity for converts transitioning to Christianity. This adaptation not only facilitated the spread of Christianity but also ensured its relevance in a rapidly changing religious landscape.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

In Praise of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, tempera on wood. Icon Museum in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Conclusion

The veneration of Mary represents a synthesis of diverse religious traditions and theological reinterpretations. Early Christianity drew heavily on the maternal archetypes of Greco-Roman goddesses like Isis, Cybele, Demeter, and Juno, adapting their attributes to align with a monotheistic framework. This cultural and religious incorporation allowed Mary to emerge as a nurturing and protective figure central to salvation history, bridging the gap between polytheistic traditions and Christian theology.

The title of Theotokos, affirmed at the Council of Ephesus, was a pivotal moment in Marian devotion, situating Mary as both the mother of Jesus and a divine intercessor. The religious significance of Mary was further deepened by connections to figures like Miriam from the Hebrew Bible, legitimizing Christianity within the framework of Jewish tradition.

The adaptation of imagery, such as Mary nursing the infant Jesus, and the establishment of pilgrimage sites reflected the take-over of pagan practices while embedding these traditions into Christian worship and presented them as ‘original’ (i.e., hiding their actual pagan origin). This duality is exemplary of Christianity’s approach to legitimizing and adapting itself within existing cultures. However, such adaptations were not unique to Christianity. Many religious or mythological figures have undergone similar transformations throughout history, as we have seen with the Greek goddess Aphrodite, who has clear origins in Mesopotamian deities.

References and further reading

- Pelikan, Jaroslav, Mary Through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture, 1998, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300076615

- Bart D. Ehrman, Lost scriptures: Books that did not make it into the New Testament, 2003, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195141825

- Clark, Elizabeth A., Women in Late Antiquity: Pagan and Christian Lifestyles, 1993, Clarendon Press, ISBN: 978-0198146759

- Ferguson, Everett, Backgrounds of Early Christianity, 2003, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802822215

- Shoemaker, Stephen J., Mary in Early Christian Faith and Devotion, 2016, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300217216

- Wilkinson, Kevin W., Women in Early Christianity: Translations from Greek Texts, 2005, Catholic Univ Of Amer PresS, ISBN: 978-0813214177

comments