Earliest depictions of Jesus

The visual representation of Jesus has undergone significant evolution over centuries, reflecting shifts in theological emphasis, political messages, cultural influences, and artistic traditions. The earliest depictions are a blend of simplicity, symbolic abstraction, and borrowing from contemporary artistic conventions. These images provide a fascinating insight into the lives and beliefs of early Christian communities and the ways they sought to express their faith visually.

Bearded Jesus between Peter and Paul, Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter, Rome. Second half of the 4th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Early Christian art and life

Early Christians often practiced their faith in secret due to persecution by the Roman authorities. Their rituals took place in private homes or catacombs, underground burial sites that also served as places for worship. These early artistic efforts were modest and symbolic, emphasizing themes of hope, salvation, and eternal life. For example, wall paintings in catacombs often featured simple and symbolic imagery, such as the fish, anchor, or Good Shepherd.

Grave niches in the Catacomb of Callixtus. This catacombs are among the largest and most important of Rome. The “Crypt of the Popes” therein once contained the tombs of several popes from the 2nd to 4th centuries. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

These paintings also provide glimpses into the rituals and practices of early Christians, including prayer, the sharing of bread in communal meals, and the emphasis on Eucharistic symbolism, such as the multiplication of loaves. Such depictions underscore the communal and spiritual focus of early Christian gatherings, as well as their theological grounding in themes of unity and divine provision.

Wall painting, Calixtus Catacomb, 3rd century. The Eucharist was often symbolized by the miraculous multiplication of the loaves. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Wall painting, Calixtus Catacomb, third century. Prayer in the orant posture. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: Possibly an image of Mary nursing the Infant Jesus. 3rd century, Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Good Shepherd, Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, 2nd half of the 3rd century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: Fresco of a Christian Agape feast, fractio panis (“the ceremonial breaking of the eucharistic bread for distribution” during the meal of Holy Communion) in the Greek chapel (Capella Greca), Catacombe di Priscilla, Rome, 2nd - 4th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: * Cubiculum of the Velata*. This fresco consists of three portraits that depict the life of a singular unnamed woman. Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, 3rd century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

After Emperor Constantine’s Edict of Milan in 313 CE, Christianity became legal and soon gained imperial support. This shift allowed for more elaborate public expressions of Christian art, including mosaics and monumental architecture. Christian artists began to adopt and transform motifs from Roman and Hellenistic art, creating a visual language that reflected both continuity with the past and the emergence of a distinct Christian identity.

Early depictions of Jesus

The earliest known depiction of Jesus is a wall painting from the Catacombs of Domitilla, dating to around 200 CE. These early representations were primarily wall paintings and frescoes found in catacombs, where Christian communities practiced their faith in secret. Such depictions served symbolic and didactic purposes, emphasizing themes of hope, salvation, and divine authority. However, it is essential to recognize a potential bias in the historical record: the surviving artworks are those that have withstood the test of time, while more fragile creations, such as works on paper or wood, may have been lost or remain undiscovered.

As Christian art developed, these depictions transitioned from simple, symbolic portrayals—like the Good Shepherd—to more elaborate mosaics and engravings. These later works conveyed theological messages and emphasized the divine authority and wisdom of Jesus, reflecting the growing institutional and public presence of Christianity.

Catacombs of Domitilla (200 CE)

One of the earliest depictions of Jesus is found in the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome, dating to around 200 CE. Many images focus on symbolic roles, such as Jesus as the Good Shepherd, emphasizing care and guidance, or the Traditio Legis, where Jesus is depicted as a teacher surrounded by his disciples. These images reflect the early Christian community’s emphasis on Jesus as a moral and spiritual authority, akin to a philosopher or teacher.

Jesus and apostles, one of the earliest depiction of the figure of Jesus. Painting in the Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome, from ca. 200 CE, showing the Traditio Legis. Christ is flanked by his disciples much like a representation of a philosopher surrounded by his students. He is represented with a gesture of authority while holding onto a scroll. He dress a toga, dress associated with authority. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Good Shepherd, another wall painting in the Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome, from ca. 200-300 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Special grave site in the Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome, showing colorful wall paintings with other Christian motifs. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another wall painting with Jesus and the twelve apostles, with the Chi-Rho sign. Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Three Magi and Mary with child. Wall painting, catacombs of Domitilla, Rome. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Healing of the paralytic, Dur-Europos (232 CE)

The house church at Dura-Europos, a Roman border city, contains some of the earliest Christian wall paintings. A striking example is the depiction of the healing of the paralytic, dating to around 232 CE. This image emphasizes Jesus’ miraculous power and compassion, key themes in early Christian theology.

Left: Baptistery wall painting: Healing of the paralytic, Dura-Europos, ca. 232 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: The Samaritan woman at the well, or possibly Saint Mary, Dura-Europos, ca. the same time. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Jesus as the Good Shepherd, St Callisto catacomb (mid 3rd century)

A depiction of Jesus as the Good Shepherd is found on the ceiling of the St Callisto catacomb, dating to the mid-3rd century. This image, showing Jesus carrying a lamb over his shoulders, symbolizes care and guidance. The Good Shepherd motif draws from both biblical imagery and Roman pastoral themes, appealing to the broader cultural audience while conveying a message of salvation and compassion central to Christian theology.

Left: Jesus as the Good Shepherd, ceiling of the St Callisto catacomb, approx. mid 3rd century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Late Roman marble copy of the a Greek statue (5th century BCE) depicting Kriophoros of Kalamis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The motif of the “Good Shepherd” was not original to Christianity. It was a common theme in Greco-Roman art and culture, where it often represented figures such as Hermes Kriophoros (“the ram-bearer”), who was depicted carrying a ram or lamb on his shoulders. This imagery symbolized protection, care, and the role of a guide, resonating with pastoral traditions deeply embedded in the Roman world. It became a common figure in series denoting the months or seasons, characteristically March or April. By adopting and adapting this familiar motif, early Christians reinterpreted it to convey their theological message, emphasizing Jesus as the compassionate shepherd who tends to his flock, representing humanity.

The blending of Christian and Greco-Roman elements in the Good Shepherd imagery served a dual purpose. It made Christian iconography more accessible to a pagan audience by incorporating familiar visual themes while simultaneously imbuing these motifs with new, distinctly Christian meanings. In the context of the St Callisto catacomb, this depiction of Jesus highlights the early Christian emphasis on pastoral care, salvation, and the intimate relationship between Christ and his followers. It also reflects the need of the early Christian community to communicate its beliefs subtly in an era when overt expressions of faith could result in persecution.

Jesus healing the bleeding woman, Catacombs Of Marcellinus and Peter (4th-6th century)

In the Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter, we find an early narrative portrayal of Jesus healing the bleeding woman. This scene emphasizes his miraculous healing powers and compassion, aligning with the Gospel accounts. Alongside this, other frescoes, such as the depiction of a baptism scene, reflect early Christian practices and rituals.

Left: Jesus healing the bleeding woman, Catacombs Of Marcellinus and Peter, Rome, 4th-6th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Baptism scene, Catacombs Of Marcellinus and Peter, Rome, 4th-6th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Hinton St Mary Mosaic (early4th century)

The Hinton St Mary Mosaic, discovered in a Roman villa in Dorset, England, is one of the earliest depictions of Jesus in Britain. Created in the early 4th century, it portrays a youthful Jesus accompanied by the Chi-Rho symbol. This mosaic serves as an evidence of the spread of Christianity into the provinces of the Roman Empire.

The Hinton St Mary Mosaic, early 4th century. This is one of the earliest depictions of Jesus in Britain. The mosaic is part of a Roman villa in Hinton St Mary, Dorset, England. It depicts a youthful Jesus along with the Chi-Rho symbol. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Bearded Jesus in the Catacombs of Commodilla (late 4th century)

A wall painting in the Catacombs of Commodilla shows Jesus with a beard, a significant departure from earlier, beardless depictions like the Good Shepherd. This bearded representation, paired with the Alpha and Omega symbols, highlights Jesus’ divine authority and wisdom. The beard, often associated with philosophers in Greco-Roman culture, serves to emphasize Jesus’ role as a teacher and divine figure

Left: Wall painting of a bust of Christ from the Catacombs of Commodilla, late 4th century. Jesus is depicted with the Alpha and Omega letters – and he has a beard. This indicates a change in the depiction of Jesus from the youthful, beardless figure of the Good Shepherd to a more mature, bearded man. The beard served to symbolize Jesus’ philosophical wisdom and divine nature. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Fresco of the Madonna Nikopoia with Saints Felix and Adauctus and the donor Turtura, Catacombs of Commodilla, late 4th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Jesus on the throne, Santa Pudenziana (4th century)

The mosaic in the apse of Santa Pudenziana in Rome, from the 4th century, is one of the earliest examples of Jesus depicted enthroned. Surrounded by saints and symbols of the Gospels, this portrayal echoes imperial iconography while establishing Jesus’ role as a cosmic ruler. The shift to depicting Jesus enthroned marked the growing influence and institutionalization of Christianity within the Roman Empire.

Apsis mosaic in S. Pudenziana, Rome, 4th century. It is among the oldest surviving Christian mosaics in Rome. Jesus is depicted surrounded by saints and the symbols of the Gospels (angel, lion, ox, and eagle) – and he sitting on a throne. The throne is not the throne of the Roman emperors, whose throne was rather plain, and thus a not symbol of imperial power, but the throne of a god (e.g., Zeus/Jupiter), symbolizing divine power and authority (and thus exceeding the power of the Roman emperors). This mosaic is one of the first in this depiction and will become a standard in Christian art, called Christ Pantocrator (the ruler of the universe). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 2.0)

Good Shepherd in the mausoleum of Galla Placidia (mid 5th century)

A mosaic in the mausoleum of Galla Placidia depicts Jesus as the Good Shepherd, now in a more regal manner, adorned with a golden halo and fine robes. Created between 424 and 450 CE, this image combines the traditional pastoral theme with imperial elements, reflecting Christianity’s evolution into a dominant and state-supported religion.

Mosaic in the entrance lunette of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, depicting Jesus as The Good Shepherd, between 424 and 450. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Wooden Doors Of Santa Sabina (5th century)

The wooden doors of Santa Sabina in Rome, dating to the 5th century, include one of the earliest surviving depictions of the crucifixion. The carvings reflect both theological and artistic developments, emphasizing the redemptive power of Jesus’ death. The detailed panels also illustrate the growing sophistication of Christian art and its integration into major architectural projects.

A depiction of the crucifixion on the wooden door of Santa Sabina, Rome. This is one of the earliest surviving depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus. Dendrochronologic and radiocarbon dating confirmed that the wood used for the door panels is from the beginning of the 5th century, therefore the carvings could date from the reigns of Celestine I (421–431) or Sixtus III (431–440). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Christ trampling the beasts, Archbishop’s chapel Ravenna (5th century)

A mosaic in the Archbishop’s Chapel in Ravenna shows Christ trampling the beasts, symbolizing his victory over sin and death. This imagery also carried a political message, asserting the authority of the Church over its enemies. Created in the 5th century, this depiction reflects both the spiritual and temporal power attributed to Jesus by the early Church.

Mosaic in the Archbishop’s chapel, Ravenna, 5th century. Christ is depicted trampling the beasts, symbolizing the victory of Christ over sin and death. The mosaic could also contain a more political message, demonstrating the authority of the Church over its enemies and heretics. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

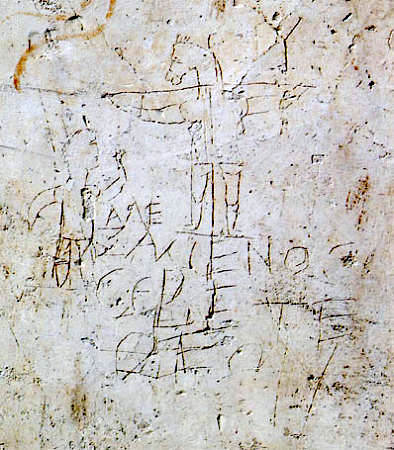

Alexamenos graffito (3rd century)

One intriguing example of early Christian art is the Alexamenos graffito, a piece of Roman graffiti etched into plaster near the Palatine Hill in Rome. Estimated to date around 200 CE, it is often considered the earliest known depiction of Jesus. The graffito depicts a figure worshipping a crucified, donkey-headed figure, accompanied by the mocking inscription, “Alexamenos worships [his] god”. While sarcastic in tone and not intended as reverent, this graffiti provides valuable insight into how outsiders perceived and ridiculed early Christian worship practices. Its significance lies in its status as the oldest surviving image referencing Jesus, albeit in a derogatory context.

The Alexamenos graffito (known also as the graffito blasfemo, or blasphemous graffito) is a piece of Roman graffito scratched in plaster on the wall of a room near the Palatine Hill in Rome. Often said to be the earliest depiction of Jesus, the graffito is difficult to date, but has been estimated to have been made about the year 200. The image seems to show a young man worshipping a crucified, donkey-headed figure. The Greek inscription approximately translates to “Alexamenos worships [his] god”, indicating that the graffito was apparently meant to mock a Christian named Alexamenos. Source (left): Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain), source (right; stone rubbing): Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Later developments

As Christianity spread and became more institutionalized, the depiction of Jesus evolved. Borrowing from pagan iconography, Christian artists began to portray Jesus with attributes such as a halo, a sign of divinity that originated in Roman and Hellenistic art. Over time, the youthful, beardless Good Shepherd was replaced by the mature, bearded Christ Pantocrator, symbolizing wisdom and divine authority. These changes reflect both the theological developments within Christianity and its interaction with broader cultural and artistic traditions.

References and further reading

- Jensen, Robin M., Understanding Early Christian Art, 2023, Routledge, ISBN: 978-1032105482

- Elsner, Jas, Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire AD 100-450, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192842015

- Paul Corby Finney, The Invisible God - The Earliest Christians On Art, 1997, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195113815

- John Beckwith, Early Medieval Art, 1964, Thames and Hudson, ISBN: 9780500200193

- Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Images of Inspiration: The Old Testament in early Christian art, 2000, Rubin Mass, ISBN: 978-9657027059

Let me know if you’d like to modify or add additional references!

comments