Is Christianity a polytheistic religion?

Christianity is widely regarded as the paragon of monotheism, standing alongside Judaism and Islam as one of the so-called Abrahamic faiths. This perception, however, demands scrutiny. While Christian theology insists on the worship of a singular, all-powerful God, its historical development and ritualistic practices reveal a cosmos teeming with divine and semi-divine figures. These figures are venerated across cultures and epochs in ways that resemble pre-Christian polytheistic traditions. Christianity, it seems, may not be as monotheistic as it claims to be.

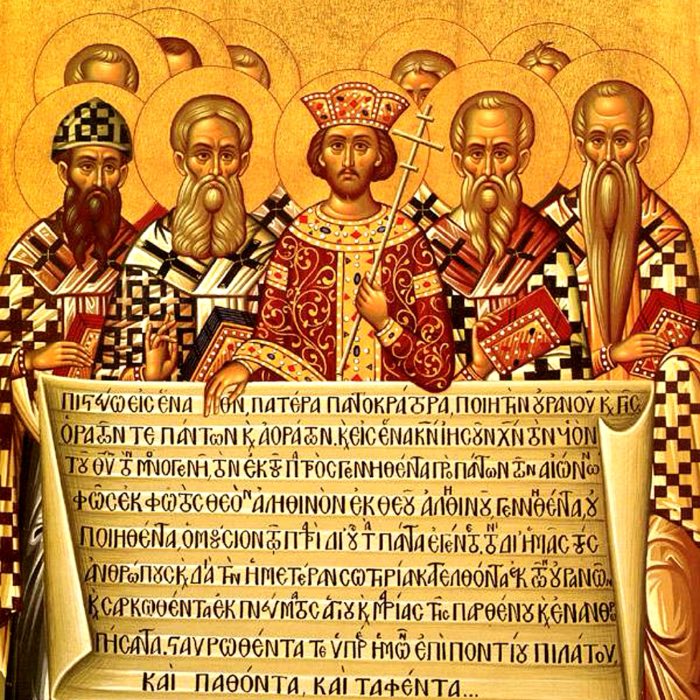

Ortodox icon of All Saint. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Trinity: The paradox of three-in-onePermalink

At the core of Christian theology lies the doctrine of the Trinity: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. This formulation, developed over centuries and formalized in the Nicene Creed, presents an immediate contradiction to classical monotheism. How can one God exist as three distinct persons? Theologians attempt to resolve this paradox with metaphysical explanations of consubstantiality — arguing that the three persons are of the same divine essence — but this does not change the practical reality: Christians effectively worship three distinct divine entities.

The Adoration of the Trinity, Albrecht Dürer, 1511. From top to bottom: Holy Spirit (dove), God the Father and Christ on the cross. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Adoration of the Trinity, Albrecht Dürer, 1511. From top to bottom: Holy Spirit (dove), God the Father and Christ on the cross. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The veneration of these three figures in Christian tradition further solidifies their practical distinctiveness. God the Father is often envisioned as a distant, supreme authority, an image shaped by the Hebrew Bible depictions of Yahweh. He is revered but rarely approached directly in personal devotion. Jesus Christ, by contrast, has been the focal point of Christian worship, with prayers directed to him, churches built in his name, and eucharistic rituals reenacting his sacrifice. The Holy Spirit is invoked in moments of divine inspiration, guidance, and charismatic experiences, mirroring how polytheistic traditions assign deities to various aspects of life and the cosmos.

Many polytheistic religions also featured triadic structures. In Hinduism, Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva represent different aspects of the divine. In ancient Egypt, Osiris, Isis, and Horus formed a sacred trio. The Christian Trinity functions similarly, offering believers a range of divine personalities to engage with: the distant, omnipotent Father, the human-like Jesus who suffered and died, and the ethereal Holy Spirit that moves through the world. This diversity within unity is far closer to polytheistic frameworks than the absolute oneness of Jewish or Islamic monotheism.

The mother of God: The elevation of Mary to divine statusPermalink

No figure in Christianity blurs the line between monotheism and polytheism more than the Virgin Mary. Officially, Christian doctrine maintains that Mary is not divine, yet the manner in which she is venerated tells a different story. From the earliest centuries of Christianity, Mary assumed roles typically reserved for goddesses in polytheistic traditions. She is the Theotokos — the “God-bearer” — a title that suggests an intimate connection to the divine.

A Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary procession during October in Bergamo, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

A Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary procession during October in Bergamo, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Throughout Christian history, Mary has been invoked as an intercessor, protector, and even co-redemptrix. In Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity, prayers are directed to her, miracles are attributed to her, and entire pilgrimages are undertaken in her honor. Shrines dedicated to her, such as Lourdes and Fatima, attract millions of devotees seeking divine intervention. If a being is worshipped, prayed to, and ascribed supernatural powers, can they truly be considered non-divine? The cult of the Virgin Mary mirrors the reverence once given to goddesses such as Isis, Cybele, and Demeter — feminine figures embodying fertility, protection, and salvation.

One of the most famous Marian shrines in the world is the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes in France. It is entirely dedicated to the Virgin Mary, based on the apparitions of Mary to a young peasant girl named Bernadette Soubirous in 1858. According to Bernadette’s accounts, the Virgin Mary appeared to her multiple times in a grotto near the town of Lourdes, identifying herself as the Immaculate Conception. The site has since become a major pilgrimage destination, attracting millions of visitors annually, many of whom seek healing from its reputedly miraculous waters. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The veneration of saints: A pantheon in disguisePermalink

Christianity’s vast network of saints further complicates its claim to monotheism. Saints function much like the deities of polytheistic religions: each has specific domains of influence, intercedes on behalf of worshippers, and receives prayers and offerings. St. Anthony helps find lost objects, St. Christopher protects travelers, and St. Jude assists the desperate. This is reminiscent of the Greek pantheon, where Hermes guided travelers, Athena granted wisdom, and Asclepius healed the sick.

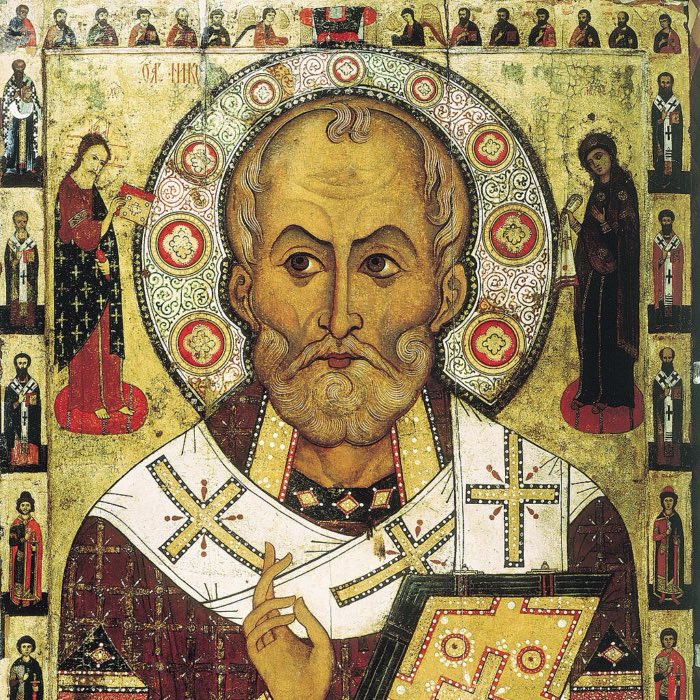

The saint John Chrysostom, Basil of Caesarea, and Gregory of Nazianzus on a late-15th-century icon of the Three Holy Hierarchs from the Cathedral of St Sophia, Novgorod. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The saint John Chrysostom, Basil of Caesarea, and Gregory of Nazianzus on a late-15th-century icon of the Three Holy Hierarchs from the Cathedral of St Sophia, Novgorod. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Unlike Jesus, Mary, Moses or Abraham, many saints were historical figures, supposedly real individuals who lived “exemplary” lives. Yet, their posthumous status transforms them into divine intermediaries, their bones and belongings becoming objects of veneration. The process of canonization mirrors ancient apotheosis — the elevation of mortals to divine status. Roman emperors were deified upon death, and Greek heroes like Heracles were worshipped as gods. The distinction between saint and deity, then, appears to be one of terminology rather than substance.

Relics and holy sitesPermalink

The Christian obsession with relics and sacred sites reflects another vestige of polytheistic traditions. The bones of saints, fragments of the True Cross, the Holy Shroud, and other purported remnants of divine figures are revered as conduits of supernatural power. Pilgrims travel vast distances to touch these objects, believing in their ability to heal, protect, and bless. In medieval Europe, entire economies revolved around the possession and display of relics, as cities vied for the most prestigious holy artifacts.

Reliquaries in the Church of San Pedro, in Ayerbe, Spain. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Reliquaries in the Church of San Pedro, in Ayerbe, Spain. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

This practice is strikingly similar to ancient polytheistic traditions, where sacred objects and places were imbued with divine presence. The Greek world had the Oracle of Delphi, the Romans had their Palladium, and Hindus today continue to venerate relics of saints and gurus. The notion that physical remnants of the divine hold power is not monotheistic — it assumes a dispersion of sacred presence across multiple locations and objects, much like the holy sites of polytheistic religions.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre: Jerusalem is generally considered the cradle of Christianity. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Church of the Holy Sepulchre: Jerusalem is generally considered the cradle of Christianity. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

ConclusionPermalink

Christianity presents itself as rigorously monotheistic, yet its theological structures and devotional practices betray a polytheistic substratum. The Trinity divides the divine into three distinct entities, each of which has been venerated in ways that parallel polytheistic worship. God the Father is perceived as a distant, omnipotent creator, often approached with solemn reverence. Jesus Christ, as the incarnate Son, has been the focal point of worship, with prayers, rituals, and entire liturgical cycles dedicated to his suffering and resurrection. The Holy Spirit, meanwhile, is invoked in moments of divine inspiration, guidance, and charismatic experiences, mirroring how polytheistic traditions assign deities to various aspects of life and the cosmos.

Beyond the Trinity, the veneration of saints introduces another dimension of polytheism into Christian practice. Saints serve as intercessors, each associated with specific causes, locations, or professions, much like the gods and demigods of ancient polytheistic religions. Churches are dedicated to them, prayers are addressed to them, and their relics are believed to hold miraculous power. The cult of relics, in particular, closely resembles the sacred objects of polytheistic traditions, where physical remnants of a holy figure were thought to convey divine presence and supernatural influence. Pilgrimages to shrines, veneration of icons, and the belief in the intercession of saints all contribute to a diffusion of sacred power that is more akin to polytheistic structures than strict monotheism.

This apparent paradox becomes more striking when considering Christianity’s historical antagonism toward polytheism. The early Church actively sought to dismantle pagan traditions, denouncing polytheism as idolatry and striving to impose strict monotheism. Yet, as Christianity spread, it absorbed and repurposed many polytheistic elements under its own framework, replacing traditional gods with saints, holy figures, and even aspects of the Trinity itself. What was once condemned as polytheism resurfaced within Christian structures, only rebranded under different names. Christianity may insist on a single God in theory, but in practice, it operates within a richly populated spiritual cosmos. In my opinion, it is, perhaps, a monotheistic religion only by name — its essence shaped by the very polytheistic traditions it claims to have eradicated.

References and further readingPermalink

- Brown, The cult of the saints: its rise and function in Latin Christianity, 2014, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226175263

- Pelikan, Jaroslav, Mary Through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture, 1998, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300076615

- Freeman, A new history of early Christianity, 2011, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300170832

- Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus became God – The exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee, 2014, Harper Collins, ISBN: 9780062252197

- Rüpke, Pantheon: A new history of Roman religion, 2020, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691211558

comments