Why Jews did not believe in Jesus: Historical and theological roots of the Jewish-Christian divergence

The emergence of Christianity in the first century CE as a distinct movement within Judaism raises fundamental questions about why the majority of Jews did not accept the figure of Jesus of Nazareth as the long-awaited Messiah. The reasons are rooted in the theological, sociopolitical, and cultural contexts of the time, as well as differing interpretations of messianic expectations. In this post, we briefly examine the historical and religious landscape of Second Temple Judaism, the nature of Jewish messianic hope, and the ways in which early Christian beliefs conflicted with those expectations, ultimately leading to the divergence between Judaism and Christianity.

The Sermon on the Mount, Carl Bloch, 1877. Jesus depicted delivering the Sermon on the Mount which included commentary on the Old Covenant. Some scholars consider this to be an antitype of the proclamation of the Ten Commandments or Mosaic Covenant by Moses from the Biblical Mount Sinai. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Messianic expectations of Second Temple Judaism

During the Second Temple period (516 BCE–70 CE), Jewish society was deeply shaped by foreign domination and internal divisions. The longing for a Messiah — an anointed one who would restore Israel’s sovereignty and fulfill the promises of the Hebrew Scriptures — was deeply rooted in Jewish eschatological thought. However, the nature and role of this Messiah were far from universally agreed upon.

The Hebrew Scriptures present a range of messianic ideas, often blending themes of kingship, priesthood, and prophecy. Texts such as 2 Samuel 7:12–16 envision a Davidic king who will establish an everlasting kingdom, while Isaiah 11:1–10 describes a ruler who will bring justice and peace to the world. Other texts, such as Daniel 7:13–14, introduce the image of a heavenly figure, “one like a son of man,” who will inaugurate divine rule. The diversity of these traditions left room for multiple interpretations of what the Messiah’s role and mission would entail.

By the first century CE, Jewish messianic hopes were heavily influenced by the socio-political realities of Roman occupation. Many Jews anticipated a military leader who would overthrow foreign oppressors and restore Israel to its former glory. This expectation of a conquering king contrasted sharply with the beliefs of early Christians regarding Jesus.

Early Christian interpretations of Jesus and the Jewish messianic ideal

The nature of Jesus’ ministry in Christian belief

Early Christians believed that Jesus’ ministry emphasized themes of love, forgiveness, and the imminent arrival of the Kingdom of God. These themes resonated with certain strands of Jewish thought but diverged from the dominant expectation of a Messiah as a political liberator.

According to early Christian writings, the proclaimed actions by Jesus — such as healing the sick, teaching in parables, and associating with marginalized groups — were seen by his followers as signs of divine authority. However, these actions did not align with the dramatic military or nationalistic interventions many Jews anticipated. For early Christians, Jesus’ focus on spiritual transformation and inclusion of social outcasts challenged traditional ideas of messianic righteousness and purity.

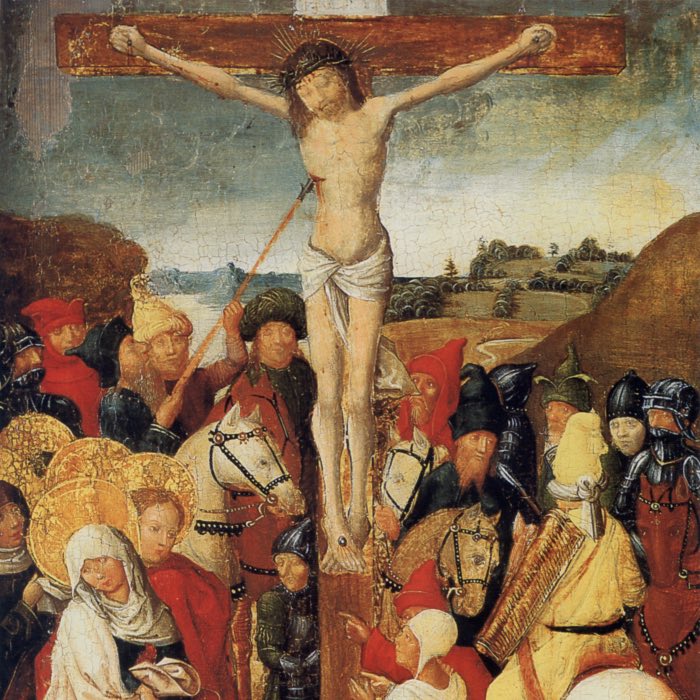

The crucifixion and its reinterpretation

Perhaps the most significant obstacle to Jewish acceptance of Jesus as the Messiah was his crucifixion. In Jewish tradition, being executed by crucifixion — a Roman method of punishment reserved for criminals and rebels — was a profound sign of failure and disgrace. Deuteronomy 21:23 explicitly states that “anyone who is hung on a tree is under God’s curse,” a passage that would have reinforced the belief that Jesus could not be the chosen one of God.

Early Christians reinterpreted the crucifixion as the central event of God’s salvific plan. For them, Jesus’ death and subsequent resurrection were seen as the ultimate fulfillment of messianic prophecy. This theological innovation involved a significant shift: the Messiah’s role was not to conquer earthly powers but to defeat sin and death, bringing spiritual redemption to humanity. This reinterpretation was alien to most Jews, who saw no need for such a departure from traditional messianic expectations.

Sociopolitical and cultural factors

Roman oppression and Jewish unity

Under Roman rule, Jewish society was marked by tensions between collaboration and resistance. Various groups, such as the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Zealots, offered differing responses to Roman domination, but all shared a common hope for divine intervention to restore Israel’s autonomy. Early Christians’ beliefs, which did not prioritize political liberation, alienated many Jews who sought immediate deliverance from oppression.

Additionally, the early Christian movement’s outreach to Gentiles created further barriers. Jewish identity was closely tied to the observance of Torah and the boundaries it established between Jews and non-Jews. Early Christian inclusion of Gentiles without requiring adherence to Jewish law was seen by many Jews as a betrayal of Jewish distinctiveness and a rejection of YHWH’s covenant.

Internal divisions within Judaism

The fragmentation of Jewish society during the Second Temple period created an environment in which competing interpretations of faith and practice flourished. The Pharisees emphasized the oral law and personal piety, the Sadducees prioritized Temple worship and priestly authority, and the Essenes retreated to the wilderness to await divine intervention. In this diverse landscape, early Christian beliefs faced skepticism from multiple quarters, as they did not align neatly with any of these established groups.

The parting of the ways

Over time, the divergence between Judaism and Christianity became more pronounced. The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE was a watershed moment, reshaping Jewish identity around the synagogue and the Torah. For Christians, the Temple’s destruction reinforced their belief in Jesus as the new locus of divine presence, further separating them from their Jewish roots.

The development of distinct Christian doctrines, such as the Trinity and the divinity of Jesus, deepened the divide. For Jews, the belief in one indivisible God was non-negotiable, and the Christian elevation of Jesus to a divine status was seen as incompatible with monotheism.

Conclusion

The Jewish rejection of Jesus as the Messiah in the early days of Christianity was rooted in a complex interplay of theological, cultural, and political factors. Early Christian beliefs about Jesus’ role and mission diverged significantly from Jewish messianic expectations, particularly regarding political liberation and the concept of a suffering Messiah. The reinterpretation of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection as central to God’s salvific plan represented a radical departure from Jewish covenantal theology.

Compounded by the sociopolitical realities of Roman rule and the internal divisions within Judaism, these theological innovations led to the eventual “parting of the ways” between Judaism and Christianity. By the late first century, Christianity had begun to establish itself as a distinct religious identity, shaped by its beliefs about Jesus and its outreach to a broader, predominantly Gentile audience.

References and further reading

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

comments