Trinity: An example of how Christianity engineered itself beyond its original scriptures

The doctrine of the Trinity, one of the central tenets of mainstream Christian theology, posits that God exists as three coequal and coeternal persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. However, when we examine the earliest Christian writings — particularly the epistles of Paul — we find little evidence that this doctrine was part of early Christian belief. Instead, it appears to have developed over several centuries through a complex process of theological debate, doctrinal evolution, and ecclesiastical consolidation. In this post, we explore how the concept of the Trinity was absent from Paul’s theology, how later Christian doctrines were shaped through reinterpretation, textual alteration, and even forgery, and how crucial elements of what we now consider core Christian beliefs were defined long after the earliest Christian communities.

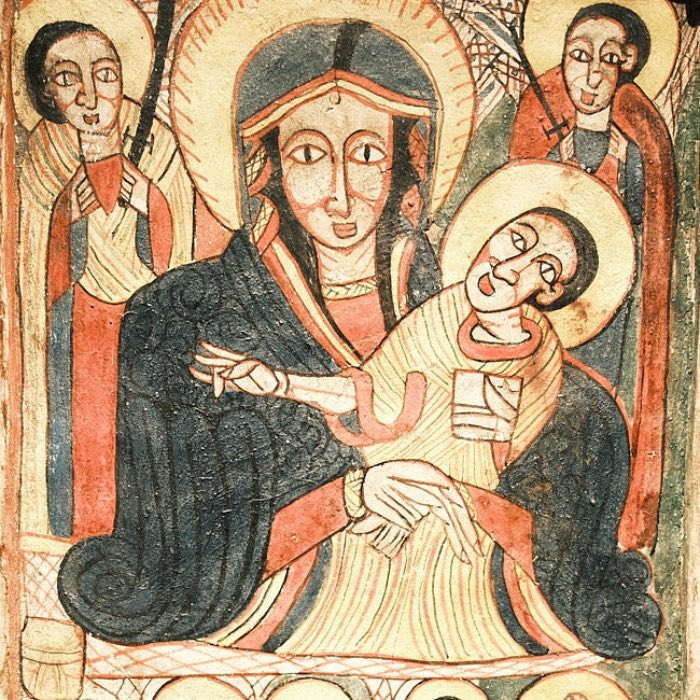

The Trinity with the globe - God the Father on the right, Jesus Christ on the left, and a white dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit above. Jesus and God depicted holding their hands on a globe, symbolizing their dominion over the world. Icon by Elias Moskos or Michail Damaskinos, 16th c. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Paul’s Theology: Monotheism and Christ as an exalted figure

Paul’s epistles, written between approximately 50 and 65 CE, constitute the earliest extant Christian texts. Throughout his letters, Paul consistently presents a monotheistic worldview rooted in Jewish tradition. For Paul, there is one God, the Father, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, who is exalted by God (1 Corinthians 8:6). This passage explicitly distinguishes between God and Jesus, affirming a form of high Christology without implying coequality or coeternity.

While Paul attributes divine roles to Jesus — such as being the agent of creation and the mediator of salvation — he does not present Jesus as ontologically equal to God. In Philippians 2:6-11, Paul describes Jesus as preexistent and divine in nature but emphasizes his subordination to God, stating that Jesus “did not consider equality with God something to be grasped” and that he was exalted by God after his resurrection. This passage reinforces the idea that Paul viewed Jesus as a distinct being who, though divine, was not equal to God in essence.

Furthermore, Paul’s references to the Holy Spirit do not indicate personhood in the Trinitarian sense. Instead, the Spirit is portrayed as God’s active presence and power in the world (Romans 8:9-11). The absence of any explicit Trinitarian formulation in Paul’s writings suggests that the doctrine of the Trinity was not a part of his theological framework.

The development of the trinity doctrine

The doctrine of the Trinity began to take shape in the second and third centuries, as Christian theologians grappled with the relationship between God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. Early Church Fathers such as Justin Martyr and Tertullian attempted to articulate a coherent theology that could reconcile monotheism with the worship of Jesus and the experience of the Holy Spirit. Tertullian, writing in the early third century, was the first to use the Latin term trinitas to describe the relationship between Father, Son, and Spirit.

“Shield of the Trinity” diagram, a visual representation of the doctrine of the Trinity. It shows the interrelationship between the Father (pater), the Son (filius), and the Holy Spirit (spiritus sanctus) as three distinct persons in one Godhead (deus). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

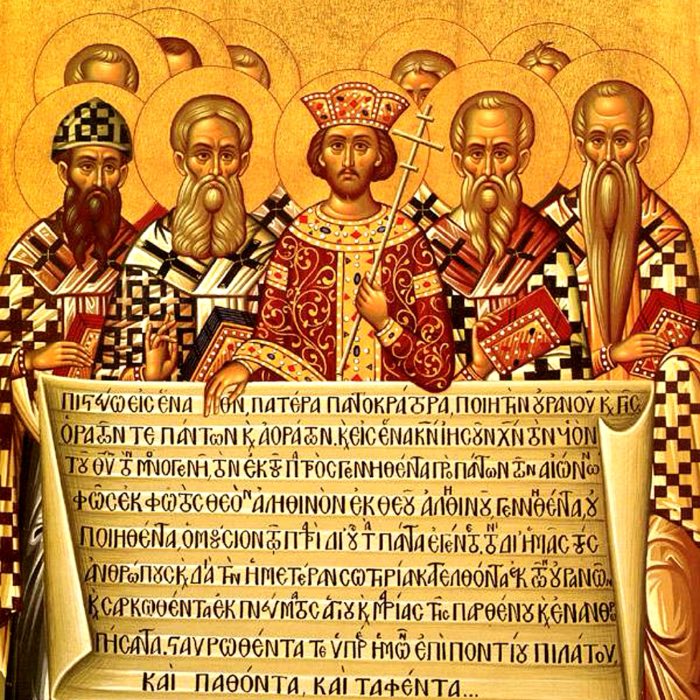

The formalization of the doctrine occurred during the fourth century, primarily through the ecumenical councils of Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381). The Nicene Creed, developed in response to the Arian controversy, affirmed the coequality and coeternity of the Son with the Father. The Council of Constantinople expanded on this by affirming the divinity of the Holy Spirit. These developments illustrate how the doctrine of the Trinity was a later theological construction, shaped by centuries of doctrinal debate and ecclesiastical politics.

Petrus Alfonsi’s early 12th-century Tetragrammaton-Trinity diagram, a probable precursor to the Shield of the Trinity. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Textual alterations and forgery in the New Testament

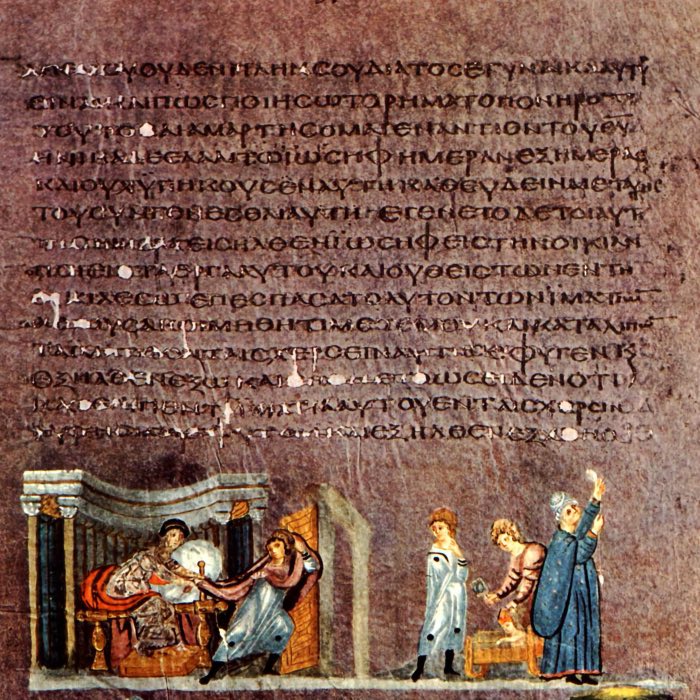

As the doctrine of the Trinity and other key Christian beliefs evolved, so too did the textual tradition of the New Testament. Scholars have identified numerous instances of textual alteration and possible forgery, where scribes modified or inserted passages to support emerging theological doctrines.

The Comma Johanneum

One of the most well-known examples is the Comma Johanneum in 1 John 5:7-8. In its fuller form, the passage reads: “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.” This explicit Trinitarian statement does not appear in the earliest Greek manuscripts and is widely regarded by textual critics as a later interpolation. The addition of this passage likely occurred in the fourth or fifth century, reflecting the growing dominance of Trinitarian theology.

Alterations in the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John, often cited as the most Trinitarian of the four canonical Gospels, also shows signs of theological development. The prologue (John 1:1-18), which presents Jesus as the preexistent logos (word) who was with God and was God, reflects a high Christology that differs significantly from the synoptic Gospels. Some scholars argue that the prologue represents an addition or redaction intended to elevate Jesus’ status in line with emerging theological views.

The ending of Mark

Another example of textual modification is the longer ending of Mark (Mark 16:9-20). The earliest manuscripts of Mark end at 16:8, with the women fleeing the empty tomb in fear. The longer ending, which includes appearances of the risen Jesus and a Trinitarian baptismal formula, is absent from early manuscripts and is considered by many scholars to be a later addition. This addition served to harmonize Mark with the other Gospels and to reinforce key doctrinal elements, including the resurrection and baptism.

Defining crucial Christian concepts

In addition to the doctrine of the Trinity, several other key Christian concepts were defined and formalized long after the time of Paul and the earliest Christian communities.

The canonization of the New Testament

The process of canonization — determining which texts would be considered authoritative scripture — was not completed until the fourth century. Prior to this, various Christian groups used different collections of texts, including Gospels, letters, and apocalyptic writings. The selection of the 27 books that now comprise the New Testament was influenced by theological, liturgical, and political considerations, with the goal of establishing a unified Christian doctrine.

Original Sin

The doctrine of original sin, which holds that all humans inherit a sinful nature due to Adam’s transgression, was not fully articulated until the late fourth and early fifth centuries. Augustine of Hippo played a crucial role in developing this doctrine, drawing on Paul’s writings in Romans 5:12-21 but interpreting them through his own theological lens. Augustine’s formulation of original sin became a cornerstone of Western Christian theology, despite its absence as a fully developed concept in the earliest Christian writings.

The nature of Christ

The doctrine of Christ’s dual nature — fully divine and fully human — was not formally defined until the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE. This doctrine, known as the hypostatic union, was developed in response to various Christological controversies, including Arianism, Nestorianism, and Monophysitism. The Chalcedonian definition sought to establish orthodoxy by affirming that Jesus was both fully God and fully man, in two natures united in one person.

Conclusion

The doctrine of the Trinity and other key elements of Christian theology were not present in the earliest Christian writings but developed over several centuries through a process of theological reflection, debate, and textual modification. Paul’s epistles, which form the foundation of early Christian theology, reflect a monotheistic belief system centered on the worship of God and the exaltation of Jesus as Lord, without implying coequality or coeternity.

The evolution of Christian doctrine illustrates how foundational beliefs can emerge gradually, shaped by historical, cultural, and theological forces. Textual alterations and later additions to the New Testament provide further evidence of how early Christian communities and later ecclesiastical authorities sought to define and solidify their faith. Recognizing this process helps us better understand the dynamic nature of religious belief and the complex history of Christianity.

References and further reading

- Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament, 2011, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199739783

- Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus became God – The exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee, 2014, Harper Collins, ISBN: 9780062252197

- Hurtado, L. W., Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, 2005, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, ISBN: 978-0802831675

- James D. G. Dunn, Did the First Christians Worship Jesus? The New Testament Evidence, 2010, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664231965

- Maurice Wiles, The Making of Christian Doctrine, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521099622

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 1 Die Frühzeit, 1996, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012632

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 2 Die Spätantike, 1996, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499601422

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

comments