How much does Christianity actually differ from Judaism?

The relationship between Christianity and Judaism has been a topic of theological, historical, and cultural debate for centuries. While Christianity is often perceived as a distinct religion with unique beliefs, practices, and institutions, a deeper analysis reveals that Christianity is deeply rooted in Judaism, to the point that it might be better understood as a Jewish sect that evolved under specific historical conditions. This post examines Christianity’s foundational elements — its theology, scriptures, ethics, rituals, and symbolism — and argues that Christianity is inherently Jewish, with some meaningful divergence from its parent tradition.

“How much does Christianity differ from Judaism?”, interpreted by DALL•E.

Shared theological foundation

At its core, Christianity inherits its theological framework from Judaism. The concept of monotheism, the belief in one omnipotent and omniscient God, originates in the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh). Christianity’s conception of God as the Creator, sustainer, and ruler of the universe directly aligns with Jewish teachings. Even the Christian innovation of the Trinity retains this Jewish framework, building on the Jewish notion of God’s multifaceted presence (e.g., the Shekinah and Ruach HaKodesh). The Christian God remains the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob — YHWH, whi is firmly Jewish.

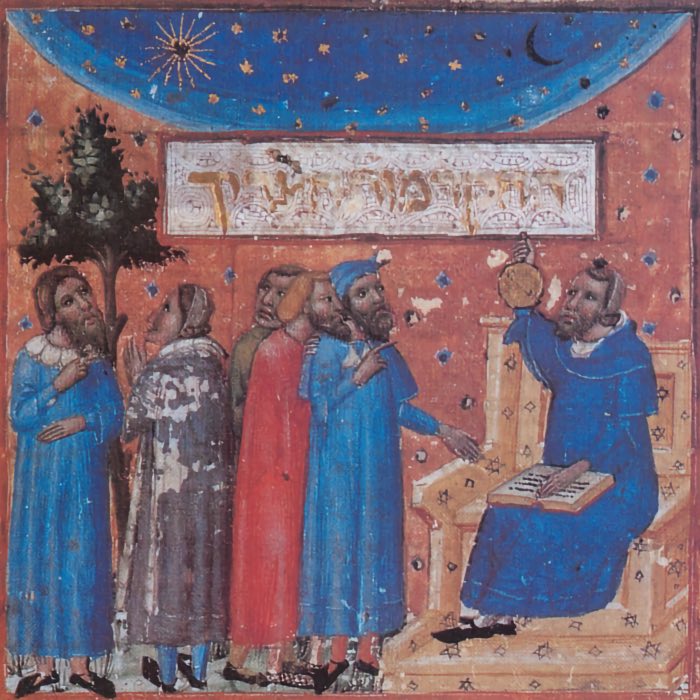

The concept of the Messiah is another key theological link. The Christian portrayal of Jesus as the Messiah draws entirely from Jewish messianic expectations rooted in texts like Isaiah, Daniel, and Zechariah. These Jewish scriptures provided the symbolic language and prophetic framework for Jesus’ role as a redeemer and the promise of a future kingdom of God. Even apocalyptic themes — central to early Christian thought — are expansions of Jewish eschatology found in works like the Book of Daniel and the intertestamental literature.

Scripture and continuity

The Christian Bible’s foundation is the Hebrew Bible, adopted as the Old Testament. These texts are not only preserved but also revered as sacred in Christian tradition, affirming their centrality. Early Christians, almost exclusively Jewish themselves, interpreted the Hebrew scriptures through a messianic lens, believing that Jesus’ life and mission fulfilled Jewish prophecies. The New Testament itself was written by Jewish authors, steeped in Jewish traditions of exegesis, storytelling, and legal argumentation.

The Gospels, for example, consistently frame Jesus as a Jewish teacher who engages in halakhic debates, interprets the Torah, and emphasizes ethical commandments central to Judaism. Paul’s epistles, often regarded as foundational to Christian theology, reflect his identity as a Pharisaic Jew, deeply engaged in Jewish scripture and legal reasoning.

Ethics and morality: A Jewish legacy

Christian ethical teachings are unmistakably Jewish. The moral precepts taught by Jesus — love of God and neighbor, care for the poor and marginalized, the pursuit of justice — are direct echoes of Jewish teachings found in the Torah and the Prophets. When Jesus summarizes the Law as “Love the Lord your God with all your heart” and “Love your neighbor as yourself”, he is quoting Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18, respectively.

Moreover, the Sermon on the Mount, often heralded as a hallmark of Christian ethics, parallels Jewish teachings from the Torah and rabbinic literature. Concepts such as the Golden Rule, forgiveness, and humility were not Christian innovations but extensions of Jewish moral philosophy.

Rituals and symbolism

Christian rituals, such as baptism and the Eucharist, also find their origins in Judaism. Baptism evolved from Jewish purification rites like mikvah immersion, which symbolized spiritual cleansing. The Eucharist, rooted in the Last Supper, reflects the Jewish Passover meal, reinterpreted by early Christians as a messianic symbol.

Even Christian liturgical practices, such as communal prayer, the reading of scripture, and the use of psalms in worship, mirror synagogue traditions. These rituals underscore Christianity’s reliance on Jewish models, both in structure and intent.

Symbolism in Christianity, from the Twelve Apostles to the figure of Jesus himself, is profoundly Jewish. The Twelve Apostles symbolize the twelve tribes of Israel, a direct continuation of Jewish symbolic tradition. Likewise, Christian art and iconography often depict figures like Moses, Noah, and David — figures who are undeniably Jewish.

Arguments against this perspective

I agree, that historically, Christianity has always been seen to be an independent religion, distinct from Judaism. Critics of the view that Christianity is inherently Jewish might raise several points:

- Radical reinterpretation of the Messiah

A common argument is that Christianity’s portrayal of the Messiah fundamentally diverges from Jewish expectations. Jewish tradition envisions the Messiah as a political and military leader who restores Israel, whereas Christianity redefines the Messiah as a spiritual savior who atones for sin through his death. This shift might represents a profound theological departure. However, the Jewish concept of the Messiah was diverse and evolving, with multiple interpretations existing in the Second Temple period. And even if the Christian understanding of the Messiah differs from some Jewish expectations, it still builds on a shared foundation of Jewish messianic hope. - The rejection of the Torah’s legal authority

Christianity’s emphasis on salvation through faith, rather than adherence to the Torah, is seen as a significant break with Judaism. Paul’s teachings, in particular, downplay the necessity of following Jewish law, which some argue creates a fundamentally new religious framework. However, this shift can be understood as a response to the destruction of the Second Temple and the need to adapt to a changing religious landscape. The early Christian community’s decision to circumcise Gentile converts demonstrates an ongoing engagement with Jewish practices, even as they reinterpreted their significance. And further more, the Torah has become a central part of Christian scripture, even if its legal requirements are thought to be fulfilled in Christ. - Inclusivity of Gentiles

Early Christianity’s mission to include Gentiles is another point of contention. Judaism traditionally views itself as a covenantal relationship between YHWH and the Jewish people, whereas Christianity reinterprets this covenant as universal. This inclusivity could be seen as a major departure from Judaism. - Development of unique doctrines

Christian doctrines, such as the Trinity, the Incarnation, and original sin, may be seen as evidence of theological innovation. These ideas, while influenced by Jewish thought, represent a synthesis with Hellenistic and Roman cultural influences – however, still rooted in Jewish monotheism. - New rituals and institutions

Christianity developed new rituals, such as the Eucharist, and established institutions like the Church. But again, these innovations were built on Jewish and pagan foundations, adapting existing practices to fit the needs of a new religious community.

Conclusion

After all personal studies I’ve conducted so far, the impression that there is no such distinct separation between Christianity and Judaism remains. The historical development of Christianity, its theological foundations, and its ethical teachings all point to a deep continuity with Judaism. While Christianity has evolved into a distinct religious tradition with its own beliefs and practices, its Jewish roots remain foundational to its identity, despite any nuances that might have been added over time.

This continuity is especially apparent when examining how early Christians adapted their message to a Gentile audience following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. Initially, Christianity functioned as a Jewish sect; however, this adaptation involved reinterpreting Jewish laws and customs to fit the broader Roman cultural and political context. Although this shift created an impression of divergence, it was less a theological departure than a strategic one.

I think, the eventual institutionalization of Christianity as the Roman Empire’s state religion played a pivotal role in reinforcing the perception of Christianity as a distinct tradition. This transformation, driven by political and cultural power, did little to alter the Jewish essence of the faith but introduced new structures and doctrines that would shape its identity moving forward.

References and further reading

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

comments