The Didache: The blueprint of a developing church and the birth of ritualized Christianity

The Didache (Teaching of the Twelve Apostles), one of the earliest Christian texts outside the New Testament, provides a fascinating glimpse into the practices and beliefs of the early Jesus movement. Likely written in the late first or early second century CE, this text serves as a manual for Christian communities, covering topics such as ethics, baptism, the Eucharist, and church organization. While it sheds light on the simplicity of early Christian life, it also reveals the early emergence of ritualized and hierarchical structures that would later define the institutional Church.

Image from page 159 of “Military and religious life in the Middle Ages and at the period of the Renaissance” (1870). Fig. 100: Peter the Hermit delivering the Message of Simeon, Patriarch of Jerusalem, to Pope Urban II. From a Coloured Drawing by Germain Picavot in the Histoirc des Croisades,a Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century (Burgundian Library, Brussels). Source: Flickrꜛ (Internet Archive Book Imagesꜛ) (license: public domain)

Image from page 159 of “Military and religious life in the Middle Ages and at the period of the Renaissance” (1870). Fig. 100: Peter the Hermit delivering the Message of Simeon, Patriarch of Jerusalem, to Pope Urban II. From a Coloured Drawing by Germain Picavot in the Histoirc des Croisades,a Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century (Burgundian Library, Brussels). Source: Flickrꜛ (Internet Archive Book Imagesꜛ) (license: public domain)

The Didache: A manual for early Christian communities

The Didache can be divided into three main sections:

- The Two Ways: A moral teaching contrasting the Way of Life and the Way of Death, emphasizing ethical behavior.

- Instructions on Rituals: Guidelines for baptism, fasting, prayer, and the Eucharist.

- Community Organization: Instructions on appointing leaders and handling traveling prophets and teachers.

At first glance, the Didache appears to offer practical advice for maintaining order and cohesion within small, scattered Christian communities. However, a closer examination reveals the beginnings of a shift from Jesus’ emphasis on inner transformation to a growing focus on external forms, rituals, and institutional authority.

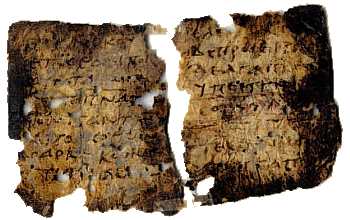

Manuscript of Didache. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The early development of ritualized practices

Baptism: A move toward standardization

The Didache prescribes specific instructions for baptism:

- It emphasizes immersion in “living water” (flowing water, such as rivers) but allows for pouring water on the head if immersion is not possible (Didache 7:1–4).

- It mandates pre-baptismal fasting for both the person being baptized and the baptizer.

While Jesus himself was baptized, likely by immersion in the Jordan River, the Didache introduces an element of rigidity by specifying methods and conditions. This standardization marks an early step toward ritualization, transforming what was originally a personal act of repentance and renewal into a formalized rite governed by prescribed rules.

The Eucharist: The roots of liturgical worship

The Didache contains one of the earliest descriptions of the Eucharist, including specific prayers over the bread and wine (Didache 9–10). It insists that only baptized believers can participate and warns against giving “holy things to dogs” (Didache 9:5).

While Jesus instituted the breaking of bread and sharing of wine as a communal and symbolic act, the Didache introduces boundaries and exclusivity. The Eucharist becomes less about the universal love and inclusion that Jesus exemplified and more about delineating an “in-group” with access to sacred rites.

Fasting and prayer: Codifying spiritual practices

The Didache mandates fasting on specific days (Wednesday and Friday) and prescribes the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer three times daily (Didache 8:1–3). While fasting and prayer were integral to Jesus’ teachings, their codification into set schedules reflects an early tendency to formalize and regulate individual spirituality.

The emergence of hierarchical structures

The Didache also reveals the early stages of church hierarchy and authority:

- Appointing Leaders: Communities are instructed to appoint bishops and deacons, who are described as worthy, humble, and faithful (Didache 15:1–2). This suggests an emerging structure of local leadership, with a growing emphasis on formal roles.

- Traveling Prophets and Teachers: The Didache provides criteria for evaluating itinerant prophets and teachers, warning against those who exploit their authority for personal gain (Didache 11:1–12). While this reflects a concern for authenticity, it also underscores the growing need to regulate and control spiritual authority.

These developments hint at a shift from the community-centered ethos of Jesus’ teachings to a model of structured leadership. Moreover, the instructions on appointing bishops and deacons foreshadow the later doctrine of apostolic succession, wherein the Church claimed its leaders derived authority directly from the apostles, who were themselves believed to be appointed by Jesus. Although the Didache predates the full articulation of apostolic succession, it reflects the early tendency to formalize leadership roles and legitimize authority through lineage, laying the groundwork for the hierarchical Church structure.

The beginning of dogmatization

The Didache reflects an early attempt to codify and unify Christian beliefs and practices:

- Ethical Rules: The Two Ways section outlines a clear moral code, emphasizing behaviors to avoid (e.g., murder, theft, idolatry) and virtues to cultivate (e.g., love, humility). While consistent with Jesus’ teachings, this codification represents an early form of dogma that reduces ethical living to a set of rules rather than an internal transformation.

- Exclusivity: By limiting participation in the Eucharist to baptized believers and emphasizing correct rituals, the Didache introduces a sense of exclusivity that contrasts with Jesus’ radically inclusive message.

This dogmatization reflects a tension between the original openness of Jesus’ teachings and the need for order and cohesion in growing Christian communities. The Didache serves as an early step in the process of defining orthodoxy, a trend that would culminate in the creeds and councils of later centuries.

The Didache and the dichotomy between teaching and institution

The Didache exemplifies the early stages of a dichotomy that would later define Christianity: the divergence between the transformative simplicity of Jesus’ teachings and the institutional structures of the Church. While the text preserves elements of Jesus’ ethical and spiritual vision, it also introduces:

- Ritualization: Transforming personal and symbolic acts into formalized rites.

- Hierarchy: Establishing roles of authority within the community.

- Exclusivity: Creating boundaries around participation in sacred practices.

These developments, while perhaps necessary for the survival and cohesion of early Christian communities, mark the beginning of a trajectory that would lead to the highly ritualized and hierarchical structures of the later Church. The Didache thus stands as both a testament to the vibrancy of early Christian life and a harbinger of the institutionalization that would follow.

Conclusion

The Didache occupies a unique place in Christian history, bridging the gap between the teachings of Jesus and the emergence of the institutional Church. Its guidelines reflect the practical needs of early communities, offering a framework for maintaining unity and identity in a rapidly expanding movement. However, they also reveal the early seeds of ritualization, dogmatization, and hierarchy that would later define the Church.

References and further reading

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 1 Die Frühzeit, 1996, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012632

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 2 Die Spätantike, 1996, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499601422

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

comments